11.6 Facelift

The extended SMAS technique in facial rejuvenation

Introduction

The evolution of aging in the human face is complex and multifactorial. Problems that the plastic surgeon confronts in midface rejuvenation include: (1) the dermal component of aging related to intrinsic and extrinsic skin changes (dermal elastosis); (2) facial fat descent; (3) facial deflation, which tends to be regionally specific; (4) radial expansion as facial fat becomes situated centrifugally away from the facial skeleton; and (5) the degree of skeletal support of the soft tissue which influences both loss of volumetric highlights, as well as the descent of facial fat.1–4 All of these factors influence facial shape changes with aging. Individual patients will exhibit various degrees of these problems at the time they request surgery, and each component of the aging face should be addressed according to individual patient needs.

Anatomic considerations

The anatomic basis that allows rhytidectomy to be performed safely is that the facial soft tissue is arranged as a series of concentric layers. This concentric arrangement allows dissection within one anatomic plane to proceed completely separate from structures lying within another anatomic plane. The layers of the face are the: (1) skin; (2) subcutaneous fat; (3) SMAS (superficial facial fascia); (4) mimetic muscles; (5) parotidomasseteric fascia (deep facial fascia); and (6) plane of the facial nerve, parotid duct, buccal fat pad, and facial artery and vein. (This information is thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 6.)

In an overview of the architectural arrangement of the facial soft tissue, the essential point is that there is a superficial component of the facial soft tissue which is defined by the superficial facial fascia and includes the SMAS and those anatomic components which move facial skin (including superficially situated mimetic muscle invested by SMAS, the subcutaneous fat, and skin). This is in contrast to the deeper component of the facial soft tissue, which is defined by the deep facial fascia and those structures related to the deep fascia (including the relatively fixed structures of the face, such as the parotid gland, masseter muscle, periosteum of the facial bones, and facial nerve branches). As the human face ages, many of the stigmata which are typically seen in aging relate to a change in the anatomic relationship which occurs between the superficial and deep facial fascia. With aging, facial fat descends in the plane between superficial and deep facial fascia, and the radial expansion of the superficial soft tissue away from the facial skeleton occurs within this plane. In the author’s opinion, these anatomic changes justify repositioning facial fat through subSMAS dissection to restore facial shape.5,6

Retaining ligaments

The communication between the superficial and deep facial fascia occurs at the level of the retaining ligaments which are discussed in Chapter 11.1. These structures fixate facial soft tissue in normal anatomic position, resisting gravitational forces.1,7 In the evolution of midface aging, the zygomatic and masseteric cutaneous ligaments bear particular attention. The zygomatic ligaments originate from the periosteum of the malar region. Their function is to fixate the malar pad to the underlying zygomatic eminence in the youthful face.

Aesthetic analysis and treatment planning

Descent of facial fat

With aging, facial fat can descend and produce significant changes in facial shape. In middle-age, as ligamentous support becomes attenuated, facial fat volumetrically becomes situated anteriorly and inferiorly in the cheek, producing a contour that is square and bottom heavy with little differential between malar highlights and submalar fat. As facial fat is situated more inferiorly in the face, middle-aged faces appear vertically longer than young faces (Fig. 11.1.4).3,4

Volume loss and facial deflation

Deflation in the aging face is a complex process which tends to be regional and age-specific. Key elements in understanding how deflation occurs have been enlightened following an elucidation of the compartmentalization of subcutaneous fat within the cheek as defined by Rohrich and Pessa.8 What these investigators realized was that the cheek subcutaneous fat, rather than being homogeneous, is compartmentalized, with each facial fat compartment surrounded by specific septal membranes and with each compartment having an independent perforator blood supply. Aesthetically, the significance of compartmentalization of facial fat is that deflation tends to occur within a specific region of the cheek, explaining why the entire cheek does not deflate homogeneously (Fig. 11.6.1).

At the risk of over-simplification, one key to understanding facial deflation is the recognition of the location of zygomaticus major muscle, which traverses from the malar eminence to the oral commissure. Deflation of the cheek lateral to the zygomaticus major muscle tends to occur independently from deflation in the malar region, medial to the zygomaticus major. For many patients, lateral cheek deflation develops at an earlier age than malar pad deflation, and is often noted in patients in their forties. Medial cheek and malar pad deflation tend to occur later in life and is responsible not only for the loss of volumetric support within the anterior cheek, but also leads to the development of what has been termed the infraorbital V-deformity. Deflation in this region results in an apparent increase in the vertical length of the lower lid, as the lid–cheek junction visually descends inferiorly into the poorly supported anterior cheek (Fig. 11.6.2).

An interesting region of deflation develops in some patients in the submalar region lateral to the oral commissure. In these patients, deflation can result in accentuation of the submalar concavity, which can become more obvious following the vertical soft tissue shifts associated with facelifting procedures. An accentuation of submalar depression lateral to the oral commissure can result in the development of what has been termed “joker lines” or cross-cheek depressions, which are a typical stigmata that a patient has undergone a facelift. Avoidance of vertical soft tissue repositioning in conjunction with volume addition in the submalar recess lateral to the oral commissure is useful in preventing the accentuation of postoperative cross-cheek depressions (Fig. 11.6.3).9

Radial expansion

Not all facial aging is vertical and a major challenge in facial rejuvenation is the radial expansion of facial soft tissue which occurs along specific areas of the midface. In youth, the skin and underlying subcutaneous fat are densely attached to the deep facial fascia by retinacular fibers which transverse between skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial fascia and insert into the deep fascia and facial musculature. Over time, with prolonged animation such as smiling, the skin along the nasolabial line is forced deep to the subcutaneous fat, positioned lateral to the nasolabial fold, attenuating these retinacular attachments. Prolonged animation therefore forces the skin and fat lateral to the nasolabial fold to expand radially and prolapse outward from the facial skeleton, accounting for much of the nasolabial fold prominence in the aging face. Radial expansion lateral to the oral commissure and marionette line similarly accounts for the prominence of the jowl in many middle-aged patients, making the older face appear square in shape and bottom heavy.4,10

Role of skeletal support in formulating a surgical treatment plan

In evaluating facial shape during preoperative analysis, there follow some of the major factors which are helpful to consider.4

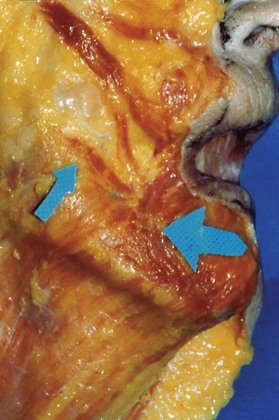

Facial width, bizygomatic diameter, and malar volume

The emphasis in facelifting over the last 30 years has focused on malar pad elevation.2,11–19 While malar pad elevation and restoration of malar highlights is an important factor in improving facial shape, it needs to be patient-specific. Many patients present preoperatively with wide faces, strong malar eminences and large malar volume, with little evidence of malar fat descent. In these individuals it is necessary to evaluate preoperatively the degree of malar pad elevation required to improve facial shape. While limited degrees of malar pad elevation can be helpful in patients who present with wide bizygomatic diameters, in general, if the malar volume is significantly enhanced in these types of individuals, the aesthetic effect is to make a wide face appear even wider on the front view postoperatively. In patients with adequate facial width, the author tends to limit both SMAS release and malar pad elevation to the lateral aspect of the zygomatic eminence such that bizygomatic diameter is not increased postoperatively (Fig. 11.6.4).

Facial length and the relative vertical heights of the lower and middle-third of the face

Compared with wide faces, patients who present with vertical maxillary excess often have long, thin faces on front view. As facial fat descends in middle age, it becomes situated anteriorly and inferiorly in the face, and the face appears even longer with age. Malar pad elevation and enhancing malar volume in these types of patients is usually beneficial. As malar volume is enhanced and bizygomatic diameter is increased, the face appears wider on the front view, detracting from relatively excessive facial length (Fig. 11.6.5).

Convexity of the malar region juxtaposed to the concavity of the submalar region

Preoperatively, an evaluation of the relationship between the malar and submalar region on front view is an essential component of aesthetic treatment planning. For many patients, a restoration in this relationship by increasing malar highlights and malar volume, in association with a restoration of concavity in the submalar region through repositioning fat internally overlying the buccinator muscle becomes a central component in improving facial shape (Figs 11.6.6, 11.6.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree