Excisional Breast Biopsy of Palpable Lesions

Stephen R. Grobmyer

Juan C. Cendan

Edward M. Copeland III

Clinical physical examination of the breast and breast self-examination are tools currently utilized in the detection of breast cancer. These modalities should be used in conjunction with annual mammographic examinations for the detection of breast cancer.

A wide spectrum of benign, potentially malignant, and malignant lesions of the breast may present as a palpable nodule or lump in the breast. When patients present with a new palpable lesion or a new lesion is detected on physical examination by a health care provider, further characterization of the lesion is warranted. Many but not all palpable lesions are detectable and assessable on breast imaging studies. When imaging studies suggest the possibility of a malignant breast lesion, image-guided percutaneous biopsy (fine needle aspiration, ultrasound-guided core, stereotactic, or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]–guided core) is preferred to achieve a pathologic diagnosis in most patients. This approach allows detailed multidisciplinary treatment planning for patients who have breast cancer and potentially limits the number of operative interventions ultimately required.

At present, we perform excisional biopsy of palpable breast lesions to the following five indications:

Palpable lesions that cannot be detected on breast imaging studies

Discordance between percutaneous biopsy results and imaging studies

Lesions strongly suspected to be consistent with fibroadenomas in younger women

Lesions in an unfavorable position for percutaneous biopsy (near chest wall or near an implant)

Patients with a bleeding diathesis in whom percutaneous biopsy may be associated with high risk of postprocedural bleeding

The assessment of patients with palpable breast lesions should begin with a detailed history and physical examination. Particular attention should be given to personal breast health history (including prior breast biopsies and prior breast operations), other cancer

history, family cancer history, and other risks factors for breast cancer. Information regarding the details of a palpable lesion includes size, rate of change in size, location in the breast, texture, method of detection (patient or other health care provider), and associated symptoms (e.g., skin changes, nipple discharge, nipple inversion, pain, tenderness). These details can provide important clinical clues regarding the etiology of a mass or nodule. The presentation of a new dominant lump in the breast of a female in her 20s, which is smooth, round, and mobile, suggests a fibroadenoma. In contrast, a firm palpable mass in the breast of a postmenopausal woman with associated overlying skin changes suggests a malignant process, either with or without a familial history of breast carcinoma.

history, family cancer history, and other risks factors for breast cancer. Information regarding the details of a palpable lesion includes size, rate of change in size, location in the breast, texture, method of detection (patient or other health care provider), and associated symptoms (e.g., skin changes, nipple discharge, nipple inversion, pain, tenderness). These details can provide important clinical clues regarding the etiology of a mass or nodule. The presentation of a new dominant lump in the breast of a female in her 20s, which is smooth, round, and mobile, suggests a fibroadenoma. In contrast, a firm palpable mass in the breast of a postmenopausal woman with associated overlying skin changes suggests a malignant process, either with or without a familial history of breast carcinoma.

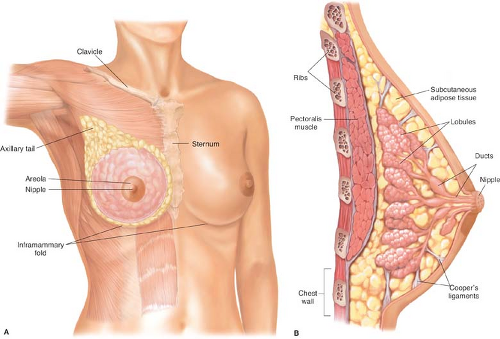

Physical examination of the breast should be performed and carefully documented. We prefer to perform breast examination with patients in both the sitting and lying positions. Mass size, texture, location, mobility, and tenderness should be recorded. Particular attention should also be given to associated findings including adenopathy (axillary or supraclavicular), nipple inversion, and nipple discharge. Normal breast anatomy is demonstrated in Figure 6.1A and B. Clinical features suggesting malignancy are shown in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Clinical Features of Palpable Breast Lesions That Suggest Malignancy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

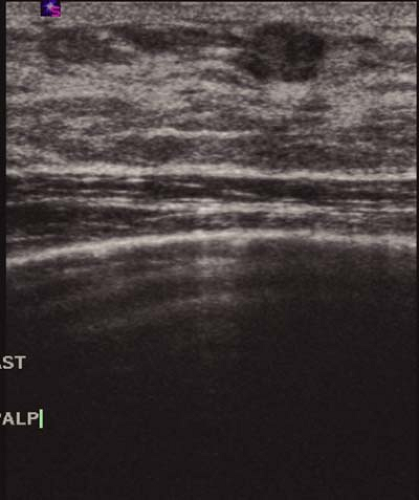

Figure 6.2 Breast ultrasound demonstrating a hypoechoic mass consistent with fibroadenoma. Fibroadenomas are typically wider than tall as shown. |

It can be difficult in some patients, particularly those with dense or fibrocystic breast tissue, to discriminate on clinical examination between normal breast changes and breast lesions that warrant further attention. Significant clinical experience is required in judging the clinical need for biopsy in these situations.

Radiographic imaging is generally indicated in the initial investigation of breast lumps or masses. The work-up should be tailored to the specifics of a given patient’s clinical presentation. This often includes a mammogram and ultrasound of the breast. Mammography is an important component of the evaluation but can be technically limited in younger patients and for lesions located in the upper medial breast. The recent addition of digital mammography to the radiologist armamentarium has somewhat eliminated the problem of dense breasts. Ultrasound is excellent for determining whether a palpable breast lump is cystic or solid and used alone may suffice for young patients who present with typical features of fibroadenoma (Fig. 6.2). Magnetic resonance imaging is not generally recommended for the evaluation of palpable breast lumps or masses.

Finally, patients with either an inherited or medically induced bleeding diathesis will need specific consideration. We prefer to work closely with the patient’s hematologist in the case of inherited disorders in an effort to minimize the operative hemorrhage risk. Likewise, and quite commonly, co-ordination will require direct communication with the patient’s other physicians, particularly cardiologists who may have initiated an anticoagulant in conjunction with placement of coronary stents. In these cases discontinuation of the anticoagulant prematurely may be of greater risk to the patient than that presented by the breast mass and a comprehensive plan must be agreed upon prior to surgery.

Before taking the patient to the operating room for biopsy, we mark the palpable abnormality with the patient awake with the patient in the supine position. This procedure helps ensure removal of the index lesion and reduces the chance of wrong site surgery. Practically, we have also found that small lesions may be somewhat obscured by infiltration of the local anesthetic agent, and marking the lesion prior to infiltration of the dermis is critical. On the day of operation, we also have available prior breast imaging studies and results of previous biopsies for review.

For operation, patients are generally placed supine on the operating room table. Excisional breast biopsy for palpable lesions can be performed under local anesthesia or general anesthesia. For patients with small or subtle palpable breast nodules, general anesthesia may be preferred in order to prevent the local anesthesia from obscuring the tactile properties of the lesion and complicating removal. For patients in whom general anesthesia is elected, our group generally prefers laryngeal mask airway to endotracheal intubation in selected patients. For local anesthesia during operation, a 1% lidocaine solution without epinephrine is utilized. We prefer local anesthetic without epinephrine, as the use of epinephrine may be associated with delayed postoperative bleeding and has been associated with sloughing of the skin at the incision margins. Bupivacaine (Marcaine) (0.25%) is administered toward the end of the operation to the operative site for prolonged local anesthesia.

An intravenous antibiotic (e.g., first-generation cephalosporin) is given within 30 minutes of the incision preoperatively. No postoperative doses of antibiotics are given. Sequential compression devices are placed on the calves to help reduce the risk of perioperative deep venous thrombosis. Chemoprophylaxis (e.g., subcutaneous heparin) against deep venous thrombosis is not utilized routinely in patients undergoing excisional breast biopsy for palpable lesions.

Technique 1: Excision of Fibroadenoma

Excision of lesions thought to be consistent with fibroadenoma makes up a large portion of excisional breast biopsies because of the frequency of this lesion, particularly in younger women. Considerations on the excision of fibroadenoma differ in subtle ways from the approach for palpable breast lesions not thought to be fibroadenoma. For patients in whom there is a strong clinical suspicion for a fibroadenoma, we prefer a periareolar incision when possible, as this approach may be associated with improved cosmetic outcomes in the postoperative period (Fig. 6.3). For lesions far from the central breast, this approach may not be technically possible. In these cases, we will utilize either an incision in the orientation of Langer’s lines (Fig. 6.4) or a transverse incision (Fig. 6.5). As a general rule, skin incisions should not be made at great distances from the incident lesion. If the lesion proves to be malignant, all the normal tissues surrounding the tunnel through which the cancer exited must be considered contaminated with breast cancer cells.

The skin of the breast and surrounding areas are prepared in a sterile fashion. The incision is made with a scalpel (no. 15 blade) and deepened through the dermal layers with electrocautery (Figs. 6.6 and 6.7). For excisional breast biopsies, we prefer use of the guarded tip cautery (Fig. 6.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree