div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

14. Vessel-Sparing Excision and Primary Anastomosis for Proximal Bulbar Urethral Strictures

Keywords

Urethral reconstructionUrethroplastyVessel-sparingNon-transectingUrethral stricture14.1 Introduction

The most frequent cause of urethral stricture in the developed world is iatrogenic, with strictures occurring in up to 33% of patients after urologic instrumentation or procedures [1].

Stricture excision and primary anastomosis is an effective treatment option for short bulbar urethral strictures, with published long-term success rates upwards of 95% when performed in the appropriate patient by experienced surgeons [2–6]. The durability of the repair is predictable, contrary to substitution techniques, for which some authors report increasing rates of recurrence over time [7].

With the increasing prevalence of prostate cancer, and the variety of different technologies to manage primary tumors, the average reported rate of urethral stricture is 5.2% [8]. Considering that Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) often occurs secondary to treatment of prostate cancer, and that the current standard of care for SUI after prostate cancer treatment is the implantation of an Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS), cuff-related atrophy is a feared complication of the AUS. The development of techniques that preserve blood supply is logical to help mitigate this problem.

The vessel sparing technique was introduced in 2007 by Jordan et al. and initially was intended for those patients with bulbar urethral stricture after radical prostatectomy, who in the future might be candidates for an AUS [9]. The indication has since expanded to all strictures of the bulbar urethra.

Contemporary publications have begun to compare transecting and non-transecting techniques with regard to sexual outcomes, showing that there is a trend for fewer erectile dysfunction (ED) events in the non-transecting group. Chapman et al. [10] demonstrated in their cohort of 352 patients that an adverse change in sexual function was less likely in non-transecting vs transecting urethroplasty (4.3% vs 14.3%, respectively). Other studies have found similar results [11] and have further found that outcomes of non-transecting techniques are comparable to transecting techniques in terms of urethral patency [12], somewhat alleviating the concern that scar tissue excision may be incomplete in this approach.

14.2 Patient Selection

The application of stricture excision with primary repair is limited by the length and the location of the scar, and should be used to repair the bulbar urethra. Excision with primary anastomosis of the penile urethra may risk the creation of chordee, as this area is not as mobile. The Vessel Sparing (VS) technique follows the same rule, with the ideal patient having a short proximal bulbar urethral stricture. Both traumatic and non-traumatic etiologies could be managed with this technique, and even recurrent urethral strictures can be favored with a VS-EPA. Some surgeons use a cut off length of 2 cm for stricture excision and primary anastomosis, while others make the decision intra-operatively based on the inner elasticity of the corpus spongiosum. There remains some controversy regarding the optimal management of bulbar strictures, with some authors favoring augmented repairs depending upon etiology [12, 13].

Initially, the vessel sparing technique was described for those patients with a urethral stricture after radical prostatectomy. The hypothesis was that by preserving the proximal blood supply of the corpus spongiosum, we could lessen the risk of cuff associated atrophy in the event these patients may require the placement of an AUS in the future. Later on, as we became more confident with the technique, we applied it to other scenarios, provided that the stricture could be excised and anastomosed without tension. We even started using the vessel sparing technique for augmented anastomotic urethroplasty, and others have followed the trend [14].

Currently we apply the VS technique to any patient with a bulbar stricture who is a candidate for excision and primary anastomosis or augmented anastomotic urethroplasty. Although posterior urethral reconstruction will be described elsewhere in this book, is noteworthy that the vessel sparing technique can be applied in this scenario [15].

14.3 Preoperative Evaluation

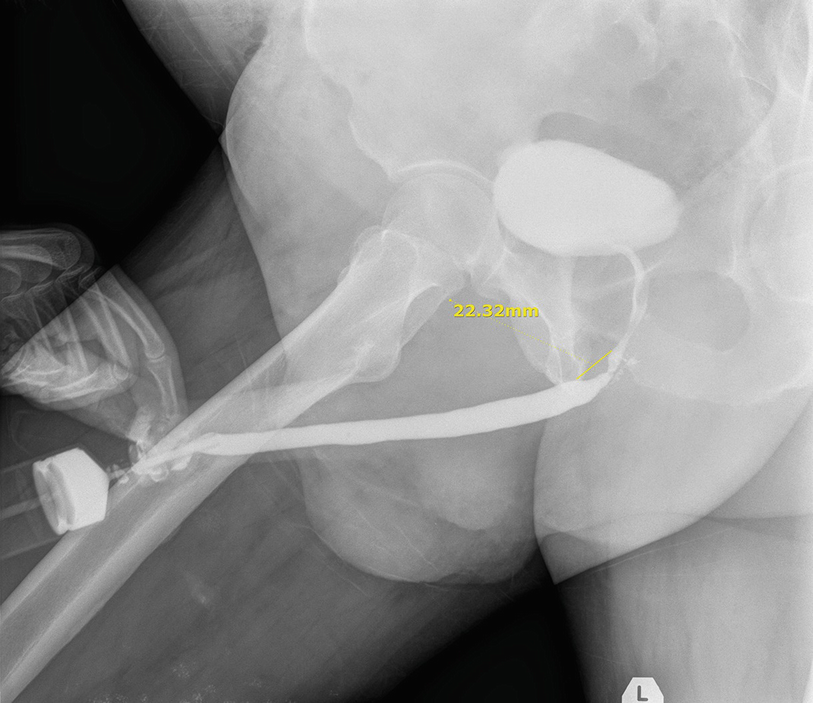

Preoperative retrograde urethrogram showing the stricture at the proximal bulbar urethra

Patients must have a sterile urine culture at the time of surgery. If necessary, patients are admitted for inpatient treatment with broad-spectrum IV antibiotics peri-operatively. In diabetic patients we recommend strict perioperative blood glucose control and generally require a preoperative glycosylated hemoglobin of less than 7%. Although studies are controversial regarding the role of hyperglycemia and increased perioperative infection, there is data that supports increased risk of infection and wound healing complications associated with poorly controlled diabetes [17].

14.4 Surgical Technique

Under general anesthesia the lower abdomen, genitalia and perineum are shaved. If a suprapubic tube is present this is exchanged sterilely. We are not placing suprapubic tubes at the time of surgery in patients who did not already have one placed preoperatively. The lower abdomen, genitalia and perineum are prepped and draped sterilely. Either high lithotomy or “social lithotomy” may be used.

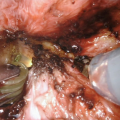

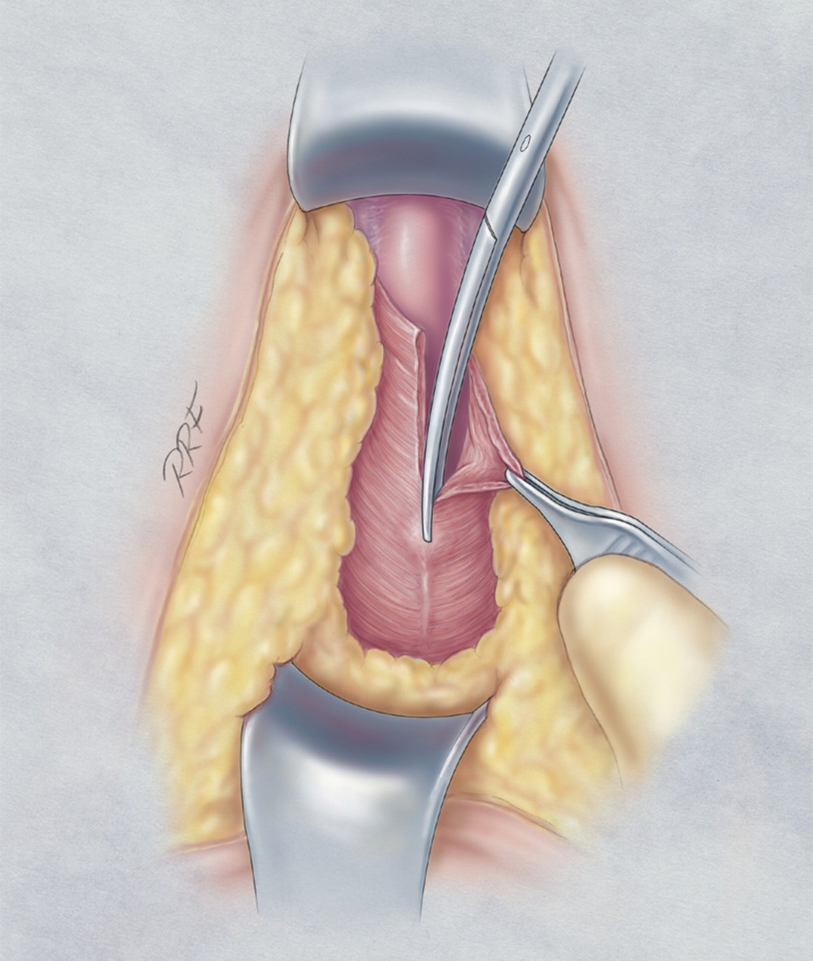

The ischiocavernosus is detached from the corpus spongiosum

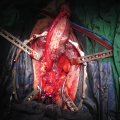

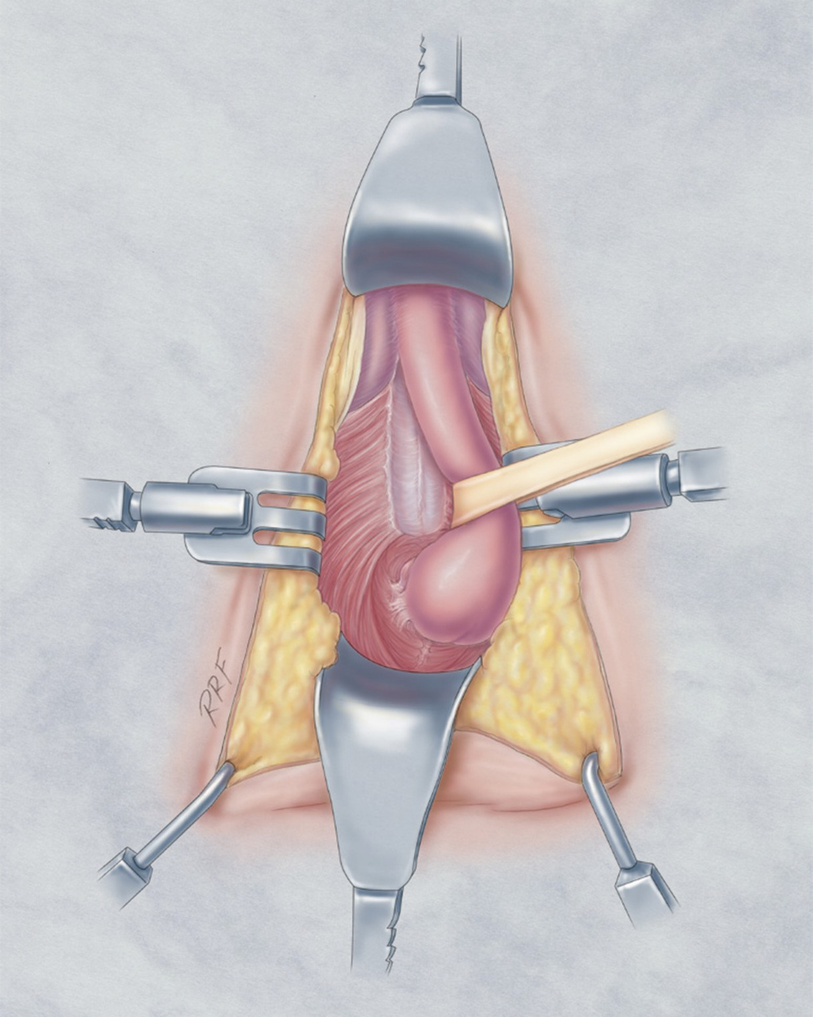

The membranous urethra and the proximal vascular structures are dissected free from surrounding tissues

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree