As the United States becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, the number of non-Caucasian patients seeking rhinoplasty is increasing. The non-Caucasian, or ethnic, rhinoplasty patient can be a surgical challenge due to the significant anatomic variability from the standard European nose as well as variability within each ethnicity. Becoming familiar with the common anatomic differences as well as the aesthetic goals in the ethnic rhinoplasty patient will assist the surgeon in attaining consistent, ethnically congruent, and aesthetically pleasing results.

The United States has become more racially and ethnically diverse over the past century, and this trend is expected to continue over the next 50 years. According to the US Census Bureau, minorities (or non-Caucasians) compose roughly one-third of the United States population and are expected to become the majority by 2042. In 2050, the US Census Bureau projects the nation to be 54% minority. The Hispanic population is projected to increase nearly 300% between 2008 and 2050, from 46.7 million to 132.8 million. The African American population is projected to increase from 46.7 million to 65.7 million.

A similar trend is occurring in plastic surgery. According to statistics by the American Society of Plastic Surgery, cosmetic plastic surgery procedures for “ethnic” patients increased by 13% between 2006 and 2007, comprising nearly a quarter of the cosmetic plastic surgery procedures performed in 2007. Since 2000, cosmetic plastic surgery procedures increased 173% in Hispanics and 129% in African Americans. Within these demographics, nose reshaping is among the top 3 most commonly requested surgical cosmetic procedures.

With this dramatic paradigm shift, it is imperative that rhinoplasty surgeons have an appreciation for the various concepts of aesthetic beauty among different races and ethnicities, as well as the unique anatomic characteristics of each population. The successful rhinoplasty surgeon must possess in his or her armamentarium the techniques to consistently modify the “ethnic” nose while maintaining facial harmony, balance, and cultural aesthetics.

Although the basic tenets of plastic surgery hold true for patients of any ethnicity, there are several important differences that distinguish rhinoplasty in the “ethnic,” or non-Caucasian patient, from Caucasian patients. This article reviews the unique anatomic characteristics of “ethnic” noses, specifically African American, Hispanic, Indian, and Middle Eastern noses. In addition, the article addresses the aesthetic objectives and reviews specific techniques to achieve consistent, harmonious, and racially congruent results.

Defining the ethnic rhinoplasty

The term “ethnic” rhinoplasty is peppered throughout the literature and is somewhat misleading, as it infers that rhinoplasty in the non-Caucasian patient is a singularly defined entity. In reality, “ethnic” rhinoplasty is a generic term that harbors a multitude of complexities. This terminology typically refers to rhinoplasty in African American, Hispanic, Indian, Middle Eastern, and Asian patients. However, even defining these specific ethnic groups is difficult as they are multiracial mixtures defined by cultural, geographic, and historical factors.

In an effort to bring order to the broad anatomic and morphologic variations among these patients, several investigators have developed subcategories within each ethnicity. The concern for lumping these ethnicities into a single category, or even multiple subcategories, is the tendency of the surgeon to adapt the patient to a prespecified treatment algorithm, rather than adapting an individualized treatment algorithm for each specific patient. While subcategories can be helpful adjuncts, it is critical that the surgeon has a command of the common yet variable anatomic features within specific races and cultures. Equally important, the surgeon must understand and respect various cultural aesthetics and be equipped with the appropriate operative techniques to achieve a successful and racially congruent result.

For the purposes of this article, the term “ethnic” (albeit a drastic generalization) refers to African American, Arabic, Indian, and Hispanic patients. These populations have several common anatomic features, as well as frequent geographic and cultural overlap. The Asian patient is discussed in a separate article elsewhere in this issue.

Nasal aesthetics in the ethnic patient

Harmony and symmetry are essential elements of beauty, and are the ultimate goals of any surgical plan regardless of a patient’s race or ethnicity. Standards of beauty in Western society have been largely influenced by Northern European characteristics. Millard described the aesthetic Caucasian female face as having clear, pale, smooth skin; large, widely spaced, soft eyes with long lashes; high cheekbones; and a medium-sized mouth with gentle lips that are not too thick. Aesthetics specific to the nose included a straight, narrow bridge; well-defined projecting tip; refined alae; and a nasolabial angle of approximately 90° to 95° in men and 95° to 100° in women. In strong contrast, the African American nose is generally characterized by a wide, low dorsum; less tip projection and definition; increased alar flaring or increased interalar width; a shorter nasal length; an acute columellar-labial angle; and a low radix. It must be borne in mind that there will be considerable variability in these characteristics from one patient to the next, given the history of the African diaspora and the multiple ethnic backgrounds of most African Americans. Each patient’s nose and his or her overall appearance will reflect this multicultural history, and this variation contributes to the complexity of rhinoplasty in this community, as well as the Indian, Hispanic, and Arabic communities that share similar features.

Given such tremendous variability within these ethnicities, it is inappropriate for the surgeon to use the aesthetic standards and techniques commonly used in Caucasian rhinoplasty patients to evaluate the ethnic rhinoplasty patient. Similarly, it is an error on the part of the surgeon to assume that the ethnic patient presenting for rhinoplasty desires to modify his or her nose to resemble that of the Caucasian or Northern European ideal. On the contrary, the surgeon must establish the aesthetic objectives of each patient individually. In past decades, arguably many ethnic patients presenting for rhinoplasty desired to look more like the “accepted standard of beauty,” a more Caucasian-appearing nose. However, the modern ethnic patient seeking rhinoplasty more likely desires to attain an attractive nose that retains its ethnic character. It is the surgeon’s responsibility to determine the exact aesthetic objective during the preoperative consultation to determine if the goals are realistic and to avoid any postoperative problems.

While there have been ideal standards described for the Caucasian female nose, an ideal standard for the African American, Indian, Hispanic, or Arabic aesthetic has yet to be established. Porter and Olson outlined objective values and proportions of African American female noses using anthropometric measurements. Similarly, Milgram and colleagues provided anthropometric analysis of female Latinas from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. However, considerable variability remains in these heterogeneous populations. Thus, a general knowledge and understanding of the more common anatomic and morphologic characteristics in patients of varying ethnicities will assist the surgeon in operative planning.

For example, classic descriptions of the African American nose include a short columella with decreased columella/lobule ratio, broad flat dorsum, slightly flaring alae, alar base width wider than the intercanthal distance, smaller nasolabial angle, increased nasofacial angle, rounded tip with ovoid nares, and greater variability in the nasal base shape. Inadequate nasal projection is frequent, with nasal projection approximately 0.5 times the nasal length, as opposed to 0.67 times the ideal nasal length in Caucasians. Bimaxillary protrusion is also common, and the upper lip is typically full with a prominent Cupid’s bow. Keeping these general differences in mind is important for the rhinoplasty surgeon embarking on nose reshaping in the African American patient, or any non-Caucasian patient with variable anatomy.

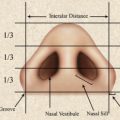

The senior author uses the following overall goals to obtain consistent aesthetic results in the non-Caucasian rhinoplasty patient ( Fig. 1 ) :

- 1.

Nasal-facial harmony

- 2.

A narrower, straight dorsum

- 3.

Enhanced tip projection and definition

- 4.

Slight alar flaring

- 5.

Normal interalar distance.

Using these guidelines and slight modifications based on the individual patient will allow the rhinoplasty surgeon to achieve harmonious aesthetic results and avoid racial incongruity.

Nasal aesthetics in the ethnic patient

Harmony and symmetry are essential elements of beauty, and are the ultimate goals of any surgical plan regardless of a patient’s race or ethnicity. Standards of beauty in Western society have been largely influenced by Northern European characteristics. Millard described the aesthetic Caucasian female face as having clear, pale, smooth skin; large, widely spaced, soft eyes with long lashes; high cheekbones; and a medium-sized mouth with gentle lips that are not too thick. Aesthetics specific to the nose included a straight, narrow bridge; well-defined projecting tip; refined alae; and a nasolabial angle of approximately 90° to 95° in men and 95° to 100° in women. In strong contrast, the African American nose is generally characterized by a wide, low dorsum; less tip projection and definition; increased alar flaring or increased interalar width; a shorter nasal length; an acute columellar-labial angle; and a low radix. It must be borne in mind that there will be considerable variability in these characteristics from one patient to the next, given the history of the African diaspora and the multiple ethnic backgrounds of most African Americans. Each patient’s nose and his or her overall appearance will reflect this multicultural history, and this variation contributes to the complexity of rhinoplasty in this community, as well as the Indian, Hispanic, and Arabic communities that share similar features.

Given such tremendous variability within these ethnicities, it is inappropriate for the surgeon to use the aesthetic standards and techniques commonly used in Caucasian rhinoplasty patients to evaluate the ethnic rhinoplasty patient. Similarly, it is an error on the part of the surgeon to assume that the ethnic patient presenting for rhinoplasty desires to modify his or her nose to resemble that of the Caucasian or Northern European ideal. On the contrary, the surgeon must establish the aesthetic objectives of each patient individually. In past decades, arguably many ethnic patients presenting for rhinoplasty desired to look more like the “accepted standard of beauty,” a more Caucasian-appearing nose. However, the modern ethnic patient seeking rhinoplasty more likely desires to attain an attractive nose that retains its ethnic character. It is the surgeon’s responsibility to determine the exact aesthetic objective during the preoperative consultation to determine if the goals are realistic and to avoid any postoperative problems.

While there have been ideal standards described for the Caucasian female nose, an ideal standard for the African American, Indian, Hispanic, or Arabic aesthetic has yet to be established. Porter and Olson outlined objective values and proportions of African American female noses using anthropometric measurements. Similarly, Milgram and colleagues provided anthropometric analysis of female Latinas from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. However, considerable variability remains in these heterogeneous populations. Thus, a general knowledge and understanding of the more common anatomic and morphologic characteristics in patients of varying ethnicities will assist the surgeon in operative planning.

For example, classic descriptions of the African American nose include a short columella with decreased columella/lobule ratio, broad flat dorsum, slightly flaring alae, alar base width wider than the intercanthal distance, smaller nasolabial angle, increased nasofacial angle, rounded tip with ovoid nares, and greater variability in the nasal base shape. Inadequate nasal projection is frequent, with nasal projection approximately 0.5 times the nasal length, as opposed to 0.67 times the ideal nasal length in Caucasians. Bimaxillary protrusion is also common, and the upper lip is typically full with a prominent Cupid’s bow. Keeping these general differences in mind is important for the rhinoplasty surgeon embarking on nose reshaping in the African American patient, or any non-Caucasian patient with variable anatomy.

The senior author uses the following overall goals to obtain consistent aesthetic results in the non-Caucasian rhinoplasty patient ( Fig. 1 ) :

- 1.

Nasal-facial harmony

- 2.

A narrower, straight dorsum

- 3.

Enhanced tip projection and definition

- 4.

Slight alar flaring

- 5.

Normal interalar distance.

Using these guidelines and slight modifications based on the individual patient will allow the rhinoplasty surgeon to achieve harmonious aesthetic results and avoid racial incongruity.

The African American, Indian, and Arabic noses

The dispersion of the African diaspora throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas occurred mostly during the Arab and Atlantic slave trades beginning in the ninth and fifteenth centuries, respectively. This dispersion represented one of the largest migrations in human history, and is also responsible for the confluence of multiple races and ethnicities throughout the world. Populations around the globe have African influences, and this likely contributes to the anatomic similarities among African Americans, Latinos, Arabs, and people from the West Indies.

These populations historically were generalized as platyrrhine, referring to the broad nature of the nose, as opposed to leptorrhine, a term used to describe the narrow nose of the Caucasian. Although these classifications are no longer applicable to a single race or ethnicity, these historical origins account for some of the similar anatomic features found among African American, Indian, Arabic, and Hispanic patients.

Anatomic Variations

There are 5 categories in which anatomic distinctions between the Caucasian nose and ethnic nose are most common: skin, the fibrofatty layer, alar cartilages, alar bases, and the bony pyramid. In these patients the skin, especially at the tip, is typically thicker, more sebaceous, relatively inelastic, and with increased subcutaneous fibrofatty tissue (2–4 mm in thickness), which causes an ill-defined tip ( Fig. 2 ).

While the alar cartilages of these patients are similar in size to those of Caucasian patients (Rohrich RJ, Schwartz R. Alar cartilage anatomy in the African American nose—a cadaver study, unpublished data, 2008), the angle between the medial and lateral crura (the “soft triangle”) is often obtuse and filled with fat and skin. In some cases, the nasal spine may be underdeveloped, and this frequently contributes to diminished tip projection.

Alar base abnormalities are frequent and can be categorized into the following 3 entities ( Fig. 3 ) :

- 1.

Increased interalar distance with the alar bases being lateral to the medial canthal lines

- 2.

Excessive alar flaring characterized by a portion of the ala extending more than 2 mm lateral to the alar attachment of the cheek

- 3.

A combination of alar flaring and increased interalar distance.

The bony pyramid is frequently characterized by a wide nasal base, low nasal dorsum, and deepened nasofrontal angle, particularly in African Americans (see Fig. 2 ). There is an occasional lack of vertical projection of the ascending process of the maxilla, which exacerbates the appearance of a widened nasal base. In this case, the flattened nasal appearance is caused by a low dorsal bridge rather than a wide nasal base. As a result, dorsal augmentation is usually recommended as opposed to osteotomies and infractures of the bony base in this scenario.

Variations more commonly seen in Arabic and Indian patients include a significant dorsal hump, nostril-tip imbalance and nostril asymmetries, droopy nasal tip with acute nasolabial angle, as well as an underprojected and hyperdynamic nasal tip. A low nasal dorsum is less common in Arabic patients, but a wide nasal base and thick sebaceous skin, especially at the tip, is very characteristic.

Rohrich and Ghavami recently reviewed 71 Middle Eastern rhinoplasty patients from North African countries (Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and Egypt), Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iran, and Oman), and other regional ethnic groups (Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Armenia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India). This review determined the more common characteristics of the Middle Eastern nose, as well as infrequently seen features of the Middle Eastern nose, listed in Tables 1 and 2 , respectively ( Fig. 4 ).

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Amorphous, bulbous nasal tip | 66 (93) |

| Thick sebaceous skin (fibrofatty soft-tissue envelope), especially at the tip | 64 (90) |

| Wide bony and middle nasal vaults | 61 (86) |

| Significant dorsal hump | 60 (85) |

| Nostril-tip imbalance and nostril asymmetries | 58 (82) |

| Droopy nasal tip with acute nasolabial (and columella-labial) angle (<80°) | 57 (80) |

| Underprojected nasal tip | 56 (79) |

| High septal angle | 51 (72) |

| High, shallow radix | 46 (65) |

| Cephalically and vertically malpositioned lower lateral crura | 44 (62) |

| Hyperdynamic nasal tip (hyperactive depressor septi nasi muscle) | 24 (34) |

| Weak and insufficient lateral, middle, and medial crura (nasal base platform) | N/A b |

a The total number of patients is 71.

b Crural morphology was observed intraoperatively and was not quantified.

| Low dorsum |

| Inadequate nasal length |

| Overprojected tip |

| Thin skin envelope with visible cartilage framework |

| Bifid tip |

| Distinct soft triangle facets |

| Round, transversely oriented nostrils |

| Obtuse nasolabial angle (and columellar labial angle) |

| Excess nostril show on frontal view |

The Hispanic nose

As with the African American and Middle Eastern populations, there is significant variability in the anatomic characteristics of Hispanic patients, which is mostly due to the variable heritage of Hispanic patients around the world. Several interpretations of the Hispanic nose have been discussed by Ortiz-Monasterio and Olmeda on the mestizo nose, Sanchez on the Chata nose, and Milgram and colleagues who provided an anthropometric analysis of female Latinas from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. More recently, Daniel described 4 Hispanic nasal types based on analysis of 25 consecutive Hispanic rhinoplasty patients in his practice. He found that irrespective of national origin, 3 common nasal deformities exist in Hispanic patients, with a potential fourth type similar to the Black or African American nose. For simplicity, he associated each type with more traditional terminology. This classification included the Castilian nose, sharing more commonalities with the European nose, the Mexican-America nose, the mestizo nose, and the Creole or Chata nose.

With such diversity within the Hispanic population, these patients demonstrate variable anatomic and morphologic features that exist along the spectrum between African and European noses. These patients display variable skin thickness, variable nasal tip projection, variable nasal dorsum, and frequently a broader nasal base but variable degrees of alar flaring ( Table 3 ).