Diagnosing and differentiating this group of mucocutaneous blistering diseases can be difficult. Despite the challenges, doing so is very important. The earlier the astute clinician can differentiate the patient with dramatic, but non-life-threatening cutaneous findings from the one who is at risk for progression to complete skin desquamation, the better the outcome for the patient. The goal of this chapter is to sort through the confusion and assist the clinician who is presented with such a patient.

Experts once believed that erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were all one disease on a spectrum of severity, with EM the mildest form and TEN the most severe. More recently, however efforts to link disease morphology with cause have led to reconsideration of that dogma. Experts now believe that EM and SJS/TEN are two separate diseases with different etiologies. EM is an acute, self-limited, but sometimes recurrent immune-mediated mucocutaneous disease.1,2 It presents most commonly as “targetoid” skin lesions in a young adult who may or may not have oral mucosal or skin blisters and has a history of infection, usually herpes simplex, but is otherwise healthy.

There remains considerable debate about what causes EM; infections, medications, malignancies, autoimmune disease, immunizations, radiation, sarcoidosis, menstruation, and other causes have been implicated.1 Most experts believe that up to 90% of cases of EM are caused by infections, with herpes simplex virus (HSV) the most commonly implicated agent.1–4 In addition to HSV, a wide range of bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic infections have also been implicated (Table 23-1). Some believe that drugs are an uncommon cause of EM, while others believe that they are a common cause and are involved in up to half of cases.1 While hundreds of drugs have been implicated, the most common culprit drugs identified are also those most commonly implicated in SJS/TEN: antibiotics (especially sulfa and penicillins), anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Experts who believe that EM is an infection-related disease would classify these drug-related cases as SJS/TEN, albeit a milder form. Regardless, it is important to recognize that when a patient presents with EM and a medication is the most likely cause, the patient should be approached with caution; this patient may actually have SJS/TEN.

| Viral | Adenovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), enterovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, hepatitis, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HSV 1 & 2, influenza, molluscum, parvovirus, poliovirus |

| Bacterial | Borrelia burgdorferi, Chlamydia, Corynebacterium, Diphtheria, Legionella, Lymphogranuloma venereum, Mycobacterium avium, lepra and tuberculosis, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Neisseria meningitidis, Pneumococcus, Proteus, Pseudomonas, Psittacosis, Rickettsia, Salmonella, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Treponema pallidum, Tularemia, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Yersinia |

| Fungal | Coccidiomycosis, histoplasmosis, sporotrichosis, dermatophytes |

| Parasitic | Malaria, trichomonas, toxoplasmosis |

Since the majority of cases of EM occur in association with HSV, most information on pathogenesis comes from studies of people with HSV-associated disease. These data suggest that EM is a cell-mediated immune response to viral antigens in involved skin. Some individuals may be genetically susceptible, but specific predisposing genotypes have yet to be clearly defined.

Most patients report the abrupt onset of skin lesions. Patients were usually previously healthy and may or may not recall symptoms of an infection in the days to weeks prior to their outbreak.

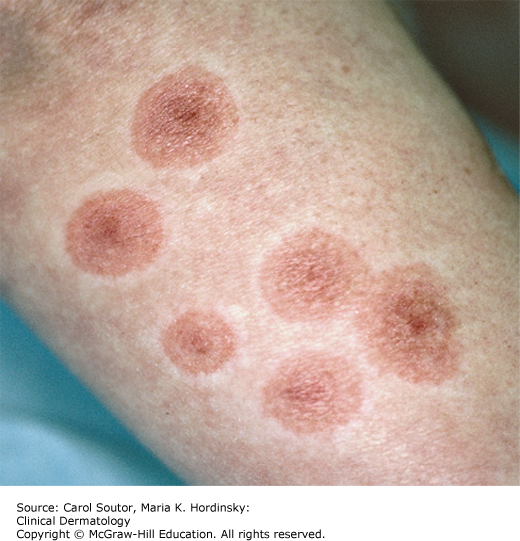

While target lesions are the classic cutaneous finding, the very name “erythema multiforme” implies a variable presentation. A “classic” target lesion is a round, well-defined pink to red patch/plaque with three concentric rings: an erythematous or purpuric center with or without bullae, a surrounding halo of lighter erythema and edema, and a third darker ring (Figure 23-1). In actual practice, target lesions are often atypical with two, rather than three zones, poorly defined borders, more extensive purpura, bullae, and appear more urticarial than targetoid (Figure 23-2). Classifying the target lesions may help establish the diagnosis, with “classic” targets more common in EM and “atypical” targets more common in SJS/TEN.

Oral mucous membrane involvement is common in EM, but is usually mild and limited to a few vesicles or erosions that may or may not be symptomatic (Figure 23-3). When more extensive mucous membrane involvement is seen, such as widespread vesicles, ulcers, and erosions in multiple sites (eg, oral, ocular, genital, and perirectal), this is considered a more severe form of the disease. The term “erythema multiforme major” has been used to describe these severe cases of EM, but it is a confusing term, often used synonymously with Stevens–Johnson syndrome. The important thing to note is that patients with classic herpes simplex related EM rarely have widespread, severe mucous membrane involvement, and in these patients it is particularly rare to have ocular lesions.3

Systemic symptoms, if present, are usually mild (fever, cough, rhinorrhea, malaise, arthralgias, and myalgias). Although skin lesions may number from few to hundreds, generally less than 10% of the total body surface area (TBSA) is involved.4 Despite its dramatic appearance, the skin is often asymptomatic. While mild pruritus and tenderness have been reported, severe pruritus might incline the clinician toward a diagnosis of urticaria and severe skin tenderness toward a diagnosis of SJS/TEN.

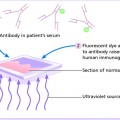

Blood studies are nondiagnostic and generally will not help differentiate EM from urticaria, or SJS/TEN. A skin biopsy is helpful and even if not strictly diagnostic of EM will help differentiate from other diagnoses, particularly SJS/TEN, which exhibits much more widespread epidermal necrosis and less dermal inflammation.4 A skin biopsy specimen demonstrating severe epidermal necrosis or graft-versus-host-like findings should increase suspicion for more severe disease.5 Patients with recurrent disease without a clear etiology might benefit from HSV serologic testing.

A typical EM patient will present with arcuate or targetoid pink patches on the extremities that may evolve into a more classic target shape and spread centrally. The patient may complain of recent upper respiratory symptoms or a HSV outbreak, but is usually otherwise healthy. Typically skin symptoms are mild (itching or tenderness) or absent and if mucous membrane involvement is present, it is limited.

✓ EM and SJS/TEN can be difficult to differentiate, particularly early on (Table 23-2). Any patient that presents with atypical target lesions, more extensive membrane and skin involvement and systemic symptoms should be considered at risk for SJS/TEN, particularly if a drug etiology is suspected. Less common causes of targetoid lesions, such as fixed drug eruption, syphilis, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and occasionally urticaria, can usually be differentiated by skin biopsy.

| Features | Erythema Multiforme | SJS/TEN |

|---|---|---|

| Target lesion morphology | “Classic” targets (identifiable 3 zone target lesions) | “Atypical” targets (macules, patches, 2 zones) |

| Distribution | Acral | Truncal, widespread |

| Erythema | Localized | Diffuse |

| % Skin detachment | <10% | >10% |

| Skin symptoms | None to mild pruritus and tenderness | Tenderness/pain |

| Mucous membrane involvement | Oral erosions may or may not be present Limited mucous membrane involvement in other locations (not ocular) | Mild to severe oral erosions always present Other mucous membranes may be involved |

| Recent HSV infection | May or may not be reported | Usually not reported |

| Nikolsky sign (lateral pressure causes skin shearing) | Negative | Often positive |

| Systemic symptoms | None to mild | Patient often febrile, systemically ill |

Self-limited disease may not require treatment. Patients with severe disease may require supportive therapy, particularly for pain and dehydration caused by oral mucous membrane involvement. Oral, intravenous, and intramuscular corticosteroids can be used to suppress symptoms. When EM is recurrent it is important to identify and if possible, treat and prevent the cause. The most common cause of recurrent EM is HSV and these patients might benefit from HSV prophylaxis with acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. Mycoplasma pneumonia infection, hepatitis C, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and other conditions have also been reported to precipitate recurrent EM and should be treated when possible.2 Uncomplicated EM is self-limited and resolves without sequelae, usually within 2 weeks. Occasionally severe, recurrent EM requires long-term immunosuppression.2

Dermatologic consultation should be considered in any patient with EM when the severity of symptoms or cutaneous findings suggests a potential diagnosis of SJS/TEN, or when EM is recurrent and the cause cannot be elucidated and recurrences prevented, or when chronic corticosteroid and/or immunosuppression is being considered. Ocular involvement warrants ophthalmologic evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree