Erythema Elevatum Diutinum: Introduction

|

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) that was initially described by Hutchinson in 1888 and subsequently by Bury in 1889. The name EED was first used by Radcliff-Crocker and Williams who separated it into two groups.1–3 The Bury type tended to occur more commonly in younger women with a history of underlying rheumatologic disease, and the Hutchinson type tended to occur in elderly males.

Epidemiology

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of EED is not entirely clear; however, the prevailing and traditional theories are based on immune complex deposition within vessel walls, complement fixation, inflammation, and subsequent vascular destruction.1 The various disease associations seen in EED (see Section “Associated Diseases”) have provided further understanding of the underlying pathomechanism of EED.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) type have proven useful for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity in various systemic vasculitides, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s), microscopic polyangiitis (MPO), polyarteritis nodosa, and Churg–Strauss syndrome.4

There are reports in the literature documenting the occurrence of IgA ANCAs in patients with neutrophil-driven dermatoses such as Henoch–Schönlein purpura, inflammatory bowel disease, and various cutaneous vasculitides, including EED.5,6 It seems likely that abnormal functioning or activation of the neutrophil, which is the primary inflammatory cell in EED, may represent the central event. Most importantly, some of the neutrophilic dermatoses, including EED, have been associated with underlying paraproteinemias (monoclonal and polyclonal IgA gammopathies)7 and hematologic malignancies. The severity of EED does not, however, appear to be dependent on the total paraprotein levels. Nevertheless, immunoelectrophoresis screening for monoclonal gammopathies as a marker of EED has been recommended.8 Hence, IgA ANCAs against yet unidentified neutrophilic antigenic targets may prove to be useful clinical markers in EED.9

In a recent analysis of the clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features in six patients with EED by Wahl et al,8 the vascular endothelium of EED was immunoreactive for CD31, CD34, vascular endothelial growth factor, and factor VIIIa but nonimmunoreactive for factor XIIIa, transforming growth factor-β, and latency-associated nuclear antigen of human herpesvirus 8. The staining properties of the endothelium in EED were compared to endothelial staining in similar lesions, including LCV, urticarial vasculitis, dermatofibromas, and capillary hemangiomas. No significant differences in the immunohistochemical staining properties were observed. The authors concluded that the chronic and recurrent nature of EED is the primary means of distinguishing it from other entities that are similar clinically and histologically.8

Clinical Findings

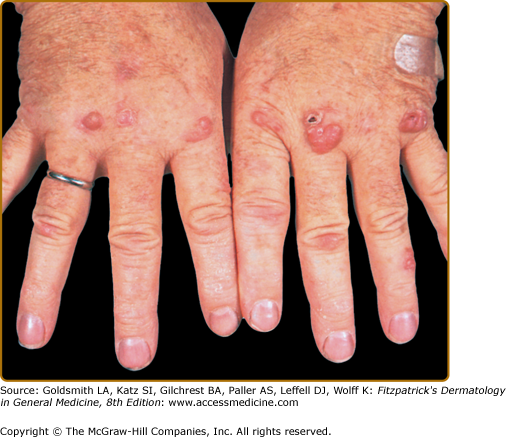

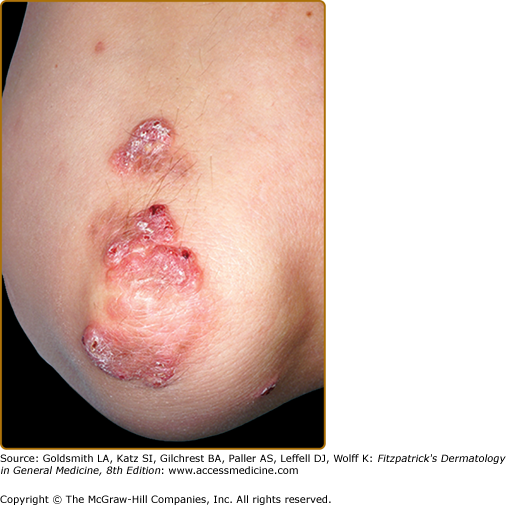

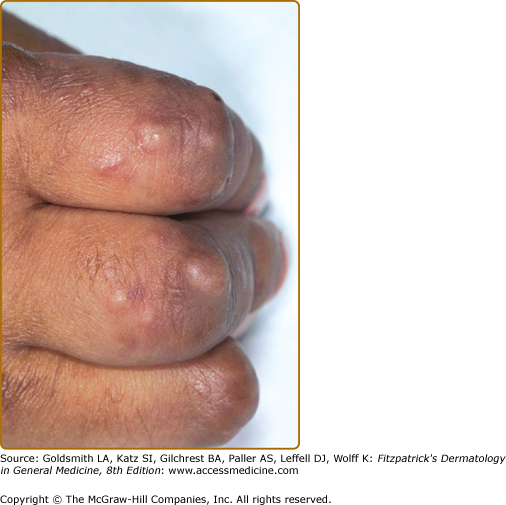

EED typically presents as multiple, persistent, symmetric, and erythematous to violaceous papules/nodules/plaques on the extensor surfaces of the hands (Fig. 165-1), elbows (Fig. 165-2), wrists, knees (Fig. 165-3), ankles, Achilles tendons, fingers (Fig. 165-4) and toes, buttocks (see eFig. 165-4.1), face, ears, legs, forearms, and genitals.1 The trunk, however, is usually spared, but may be involved rarely.10 Other atypical sites of involvement include the retroauricular and palmoplantar regions.1,2,10 Overlying epidermal changes, such as vesicles, bullae or ulcers, may be present. Lesions may be exacerbated by cold exposure and may become more raised, erythematous, and firm in the evening.11–13

With time, the lesions may become firmer and develop a yellowish-brown coloration, resembling xanthomata (see Fig. 165-2). These eventually heal with dyspigmentation. The onset of new lesions may be associated with symptoms of pruritus, burning, stinging sensations, paresthesias, or may be completely asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms, including fever and arthralgias, are seen commonly.1,14

The clinical presentation of EED in human immunodeficiency virus-infected (HIV-infected) individuals is somewhat different and can mimic lesions of Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis usually seen in immunosuppressive states.15 Nodular lesions have been reported in HIV-infected patients.

Laboratory Findings

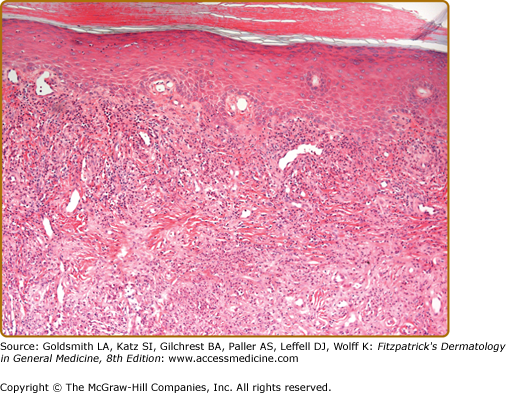

Histopathologic findings are predominantly those of a chronic LCV, with thickening of blood vessel walls, mural and luminal neutrophilia, vascular occlusion, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, endothelial cell swelling, leukocytoclasia, and dermal neutrophilia with lymphocytes (Fig. 165-5). Epidermal changes of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, ulceration, subepidermal edema, and bulla formation may also be observed.1,3,16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree