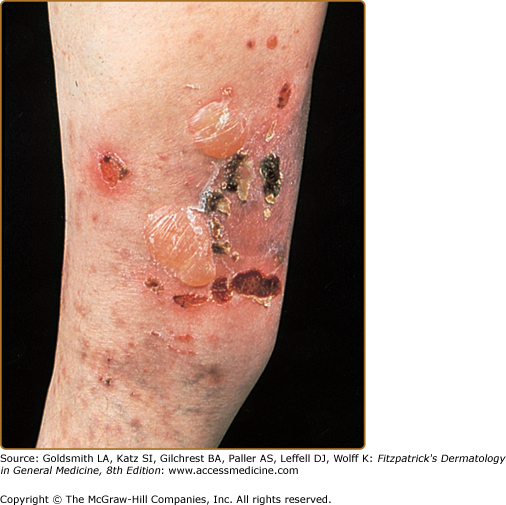

Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a sporadic autoimmune bullous disease of unknown etiology and with no gender, ethnic, or geographic predisposition. Although EBA does not have a Mendelian pattern type of inheritance, there may be some genetic predisposition to EBA and autoimmunity in African-Americans who live in the southeastern part of the United States.1 African-American patients in the southeastern part of the United States who have either EBA or bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have a high incidence of the HLA-DR2 phenotype. The calculated relative risk for EBA in HLA-DR2+ individuals is 13.1 in these patients. These results also suggest that EBA and bullous SLE are immunogenetically related and that either the HLA-DR2 gene is involved with autoimmunity to anchoring fibril collagen or is some sort of a marker for some other gene that exists in linkage disequilibrium with it.1

Etiology and Pathogenesis

EBA is a chronic, subepidermal blistering disease associated with autoimmunity to the collagen (type VII collagen) within anchoring fibril structures that are located at the dermal–epidermal junction (DEJ). Although the precise etiology of EBA is unknown, most of the evidence suggests an autoimmune etiology. The immunoglobulin (Ig) G autoantibodies to type VII collagen are associated with a paucity of normal-anchoring fibrils at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) separating the epidermis from the dermis and poor epidermal–dermal adherence. Although it is an acquired disease that usually begins in adulthood, it was placed in the category epidermolysis bullosa (EB) approximately 100 years ago because physicians were struck by how similar the clinical lesions of EBA were to those seen in children with hereditary dystrophic forms of EB. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) of perilesional skin biopsies from EBA patients reveals IgG deposits at the DEJ.2 EBA antibodies bind to type VII collagen within anchoring fibrils (see Chapter 53).3,4

Anchoring fibrils anchor the epidermis and its underlying BMZ to the papillary dermis. Patients with hereditary forms of dystrophic EB (see Chapter 62) and EBA have decreased numbers of anchoring fibrils in their DEJ. This paucity of anchoring fibrils is associated with two similar clinical phenotypes, EBA and dystrophic forms of hereditary EB, because both diseases are characterized by skin fragility, subepidermal blisters, milia formation, and scarring. Although both EBA and hereditary forms of dystrophic EB are etiologically unrelated in terms of their underlying pathogenesis, they share the common feature of decreased anchoring fibrils. In the case of dystrophic forms of hereditary EB, the cause of decreased or absent anchoring fibrils is a genetic defect in the gene that encodes for type VII collagen α chains that ultimately results in small, nonfunctional, or decreased anchoring fibrils.5,6 The gene coding for type VII collagen is located on the short arm of chromosome 3, approximately 21 cm from zero.7 The gene defects involved in hereditary forms of dystrophic EB have been identified at variable locations, but the severity of the disease appears to correlate with the degree of type VII collagen and anchoring fibril perturbations.6 In EBA, the IgG autoantibodies binding to the type VII collagen α chains result in decreased anchoring fibrils, but the pathway leading to this reduction is unknown. It may be that type VII collagen α chains that are newly synthesized but decorated with EBA autoantibodies cannot form triple-helical structures and stable anchoring fibrils. Healed burn wounds that have been covered with cultured keratinocyte sheets also have decreased numbers of anchoring fibrils within the first year after transplantation, and this is associated with spontaneous blister formation, shortened suction blistering times, and skin fragility.8 These observations provide indirect evidence that anchoring fibrils play a role in maintaining adherence between the epidermis and dermis.

The type VII collagen α chain has a molecular mass between 250 and 320 kDa, and the collagen consists of a homotrimer of three identical α chains (see Chapter 53). Each α chain consists of a large globular noncollagenous amino terminus called the noncollagenous 1 (NC-1) domain that is approximately one-half the entire mass of the α chain. Next, there is a helical domain with typical glycine-X-Y repeats. At the carboxyl terminus is a second globular noncollagenous domain, NC-2, that is much smaller than NC-1.9 Most EBA autoantibodies recognize four predominant antigenic epitopes within the NC-1 domain and do not recognize the helical or NC-2 domains.10,11 There may be something intrinsically “antigenic” about the NC-1 domain because the available monoclonal antibodies that have been generated against type VII collagen specifically recognize only NC-1 subdomains.

A reduction in the number of anchoring fibrils is seen in lesional and perilesional skin of EBA patients, but the pathway leading to this reduction is unknown.

Several independent lines of evidence have implicated autoimmune responses as a key element in the pathogenesis of EBA. First, the pathogenic role of EBA antibodies is suggested by the observation that when patients with SLE develop autoantibodies to the EBA antigen, they develop widespread skin blisters and fall into a subset of SLE called bullous SLE.12 This “experiment of nature” suggests that EBA autoantibodies are pathogenic and capable of inducing disadherence between the epidermis and dermis. Secondly, direct proof that EBA autoantibodies are pathogenic comes from recent passive transfer studies. We immunized rabbits and raised a high titer antiserum to the NC-1 domain of human type VII collagen. We injected this antibody into hairless immune competent mice, and the mice developed bullous skin disease with many of the features of EBA in humans.13 The mice developed subepidermal blisters and lost nails on their feet. They also had circulating NC-1 antibodies in their blood and anti-NC-1 IgG antibody deposits at their DEJ. In addition, the mice had murine complement deposits at the DEJ induced by the autoantibody–antigen complex.13 Another study by Sitaru and colleagues14 showed that the injection of rabbit polyclonal antibodies to the NC-1 domain of mouse type VII collagen into mice also induced subepidermal skin blisters that were reminiscent of human EBA.14 Further, we have also affinity purified human EBA autoantibodies against an NC-1 column and injected them into mice. The mice then developed clinical, histologic, immunologic, and ultrastructural features akin to human EBA.15 Taken together, these successful passive transfer experiments and the observations with bullous SLE strongly suggest that EBA autoantibodies are “pathogenic” and capable of causing epidermal–dermal separation in skin.

In addition to a passive transfer animal model of EBA, Sitaru and colleagues16 have established an active EBA animal model by immunizing certain strains of mice with fragments of the noncollagen domain (NC-1) of murine type VII collagen. In these animal models, activation of complement by the alternative pathway and NADPH oxidase for neutrophil action are required for the development of murine EBA.17,18 The murine models of EBA with these requirements for components of inflammation may better reflect the inflammatory subsets of EBA than the classical noninflammatory mechanobullous EBA phenotype since it is known that not all EBA patients have complement-fixing antibodies or a pathology involving neutrophils. Alternatively, the murine model could reflect early processes in the development of all EBA that is later modulated in certain EBA patients by their intrinsic immune regulatory processes. The next advance in understanding the pathogenesis of EBA will be linking the pathogenic mechanistic steps involved in the disease with the patient’s clinical phenotype of disease (see Section “Clinical Findings”).

Clinical Findings

If a patient presents with bullae on the skin with no reasonable explanation despite a thorough history and physical examination, three tests should be done: (1) a skin biopsy for routine hematoxylin and eosin histology, (2) a second biopsy juxtaposed to a lesion but on normal-appearing skin for DIF, and (3) a blood draw to test for antibodies against the BMZ and/or type VII collagen by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

The cutaneous lesions of EBA can be quite varied and can mimic other types of acquired autoimmune bullous diseases. The common denominator for patients with EBA is autoimmunity to type VII (anchoring fibril) collagen. Although the clinical spectrum of EBA is still being defined, there are at least five clinical presentations: (1) a classic presentation, (2) a bullous pemphigoid (BP)-like presentation, (3) a cicatricial pemphigoid (CP)-like presentation, (4) a presentation reminiscent of Brunsting–Perry pemphigoid with scarring lesions and a predominant head and neck distribution, and (5) a presentation reminiscent of linear IgA bullous dermatosis or chronic bullous disease of childhood.

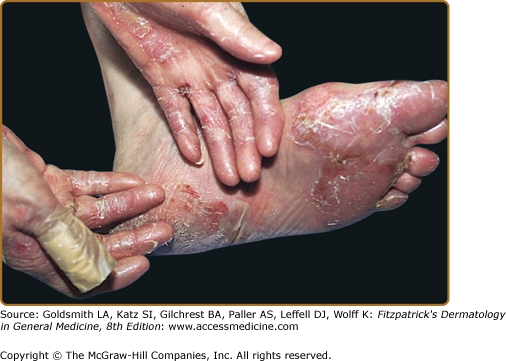

The classic presentation (Figs. 60-2 and 60-3A) is of a noninflammatory bullous disease with an acral distribution that heals with scarring and milia formation. This presentation is reminiscent of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT; see Chapter 132) when it is mild and of the hereditary form of recessive dystrophic EB when it is severe (see Chapter 62). The classic form of EBA is thus a mechanobullous disease marked by skin fragility. These patients have erosions, tense blisters within noninflamed skin, and scars over trauma-prone surfaces such as the backs of the hands, knuckles, elbows, knees, sacral area, and toes (see Figs. 60-2, 60-3A, and 60-4). Some blisters may be hemorrhagic or develop scales, crusts, or erosions. The lesions heal with scarring and frequently with the formation of pearl-like milia cysts within the scarred areas (see Fig. 60-3A). Although this presentation may be reminiscent of PCT, these patients do not have other hallmarks of PCT, such as hirsutism, a photodistribution of the eruption, or scleroderma-like changes, and their urinary porphyrins are within normal limits. A scarring alopecia and some degree of nail dystrophy may be seen.

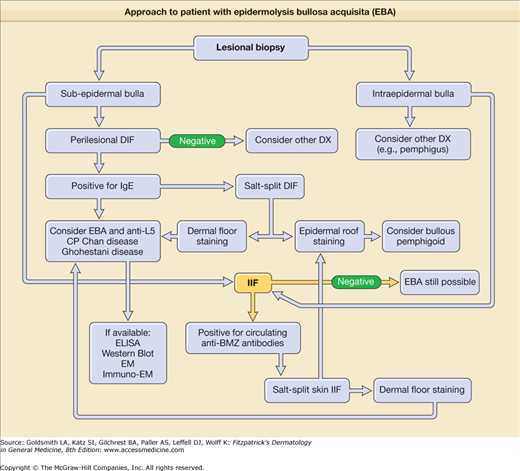

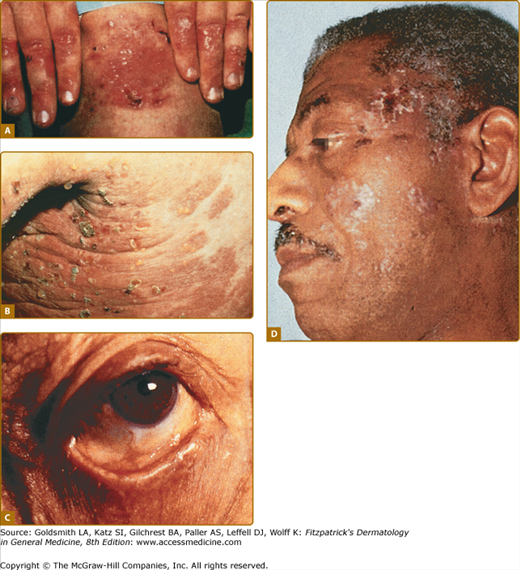

Figure 60-3

A. Classic presentation of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with scarring and milia over trauma-prone areas of skin. B. Bullous pemphigoid-like presentation of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with a widespread inflammatory vesiculobullous dermatosis. C. Cicatricial pemphigoid-like presentation of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with a mucosa-centered bullous scarring eruption. D. Brunsting–Perry pemphigoid-like presentation of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with bullous and scarring lesions predominantly on the head and neck.

Although the disease is usually not as severe as that of patients with hereditary forms of recessive dystrophic EB, EBA patients with the classic form of the disease may have many of the same sequelae, such as scarring, loss of scalp hair, loss of nails, fibrosis of the hands and fingers, and esophageal stenosis.19

(See Chapter 56)

A second clinical presentation of EBA is of a widespread, inflammatory vesiculobullous eruption involving the trunk, central body, and skin folds in addition to the extremities.20 The bullous lesions are tense and surrounded by inflamed or even urticarial skin. Large areas of inflamed skin may be seen without any blisters and only erythema or urticarial plaques. These patients often complain of pruritus and do not demonstrate prominent skin fragility, scarring, or milia formation. This clinical constellation is more reminiscent of BP (see Figs. 60-3B and 60-4) than a mechanobullous disorder. Similar to BP, the distribution of the lesions may show an accentuation within flexural areas and skin folds.