CHAPTER 15 Endoscopic mid and lower face rejuvenation

History

The concepts and principles for the endoscopic midface procedure currently employed began in the 1980s when plate fixation for zygomatic fractures was introduced. These plates necessitated wide subperiosteal stripping for exposure and fixation. Postoperatively, patients developed significant soft tissue ptosis that was ascribed to this extensive dissection without adequate soft tissue suspension. Since these plates were to be removed at a second stage, resuspension of the soft tissues through a subperiosteal dissection was subsequently carried out at that time. To our surprise we failed to restore the preoperative aesthetics through this approach. In some instances there was excess bunching and fullness in the lower lid necessitating removal of substantial amounts of lower lid skin and orbicularis oculi muscle that ultimately resulted in very unpredictable lower lid outcomes. Suffice it to say that the final outcome on the operated side seldom succeeded in achieving aesthetic symmetry with the normal unoperated side.

These disappointing results prompted a fresh cadaver anatomic study of a supraperiosteal approach specifically aimed at remaining above the zygomaticus major muscle and below the orbicularis oculi muscle. This approach had the advantage of mobilizing the orbicularis oculi muscle, malar fat pad, and high SMAS as a composite unit while avoiding the downward force of the zygomaticus major muscle by leaving its origin attached to the bone. This anatomic approach was adopted as an aesthetic procedure and was reported in the 1990s as an extended temporal lift.1 It reached its full aesthetic value as an endoscopic procedure in the late 1990s where motor innervation to the lower eyelid was further defined and precise suture fixation of the orbicularis muscle identified in a manner that allowed correction of most lower lid problems.2,3 Complete with this evolution of facial aesthetics was the simultaneous recognition that the midface procedure necessitated adjustments in lower facial rejuvenation that emphasized the neck and jawline, and at the same time eliminated the lateral sweep deformity as described by Hamra.3

Physical evaluation

• Upper lid fullness corrected at least in part by brow repositioning.

• A widened malar-orbicular crescent.

• A deepened tear trough and malar groove.

• An accentuated lid/cheek junction.

• Improved aesthetics with two point elevation of the lateral brow and malar complex.

Anatomy

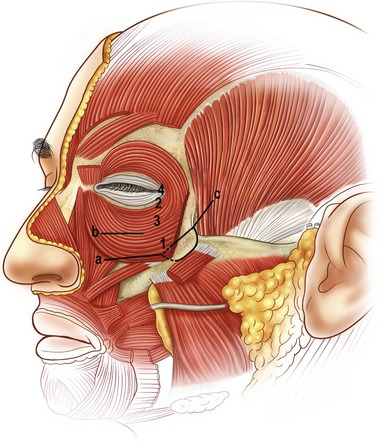

A key goal in the forehead and midface portion of this procedure is the mobilization and release of the orbicularis oculi muscle from the orbit. The release is above rather than below the periosteum. We feel this obtains more shaping of the brow and an effective shift of the preseptal upper lid orbicularis, which eliminates the need for upper eyelid muscle resection. Critical to the mobility of the orbicularis oculi muscle is the release of the preseptal muscle from its attachments to the orbital rim. In the lower lid this attachment has been identified as the zygo-orbicular ligament.3 Laterally this same attachment along the outer rim surface represents the superficial head of the lateral canthus, while in the upper lid fusion between the orbit and orbicularis is anatomically similar to that described in the lower eyelid. This zone of fusion serves as a retaining structure to the brow.4 The selective release, mobilization, and fixation of these retaining structures of the orbicularis oculi muscle are important to achieving the desired periorbital aesthetics. Precise suture placement in the four target zones of the orbicularis oculi muscle allows lower lid shaping and control based on the requirements of the lid morphology (Fig. 15.3).

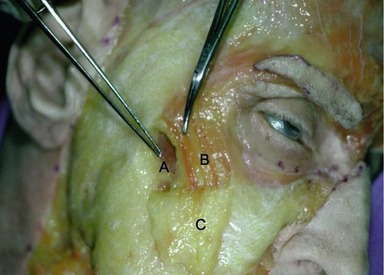

A second key in achieving the desired aesthetic relationship between the midface and lower eyelid depends on the release and mobilization of the malar retaining ligament.5 This ligament consists of a dime-sized zone of fibrous attachments extending from the periosteum of the zygomatic eminence to the subcutaneous tissue of the cheek. The lateral and most dense portion of this ligament arises from the lateral border of the zygoma where the masseter muscle attaches. Fibers continue through the origin of the zygomaticus major muscle and extend superficially through the malar fat pad and lateral border of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Fig. 15.4). By releasing these fibers above the zygomaticus major muscle, the midface can be moved vertically, eliminating the downward force of the zygomaticus muscle that is typically produced in a subperiosteal approach. The anatomic components of this midface movement include the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle, the malar fat pad, and the upper or high SMAS.

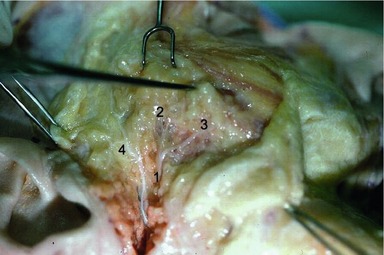

The third anatomic key of the eyelid midface procedure is the sparing of the orbicularis oculi muscle. This is achieved by avoiding: muscle division, muscle resection, and muscle denervation. The motor innervation to the lower lid orbicularis not only arises medially from the zygomatic branch running deep to the zygomaticus major muscle, but also laterally from branches arising from the zygomatic branch before it passes beneath the zygomaticus major muscle6 (Fig. 15.5). These lateral branches enter the inferior lateral belly of the orbicularis muscle. While the medial innervation is integral to the blink reflex, the lateral innervation is equally important to lower lid pretarsal muscle tone. It is for this reason that transpalpebral division of the orbicularis muscle is avoided and a transconjunctival approach is used when access to fat or the septum is needed.

The relevant anatomy to lower facial rejuvenation hinges on the mobilization and fixation of the structures previously described. The important fact to be recognized is that the upper or high SMAS movement has already occurred. Hence, when dealing with the lower face, a skin only or low SMAS skin procedure is indicated. The vector of the low SMAS or skin procedure is placed in a lateral direction along the jawline. Emphasizing a strong jawline vector while avoiding the additional lateral tension on the high SMAS, avoids the tightening and the flattening of the malar remnants with the creation of submalar traction lines that have been referred to as “lateral sweep.”7 In the majority of patients who have significant lower facial laxity my preference is a separate skin and SMAS flap procedure. The SMAS is elevated in continuity with the platysma muscle so that a strong lateral vector SMAS-platysma pull is achieved along the jawline (Fig. 15.6). The skin is closed with minimal preauricular tension. The lateral vector SMAS platysma movement generally fails to provide adequate tension in the submental area from the hyoid to the mandible. A medial plication in this zone is usually incorporated. Platysma muscle division is reserved for banding and for very obtuse necks.