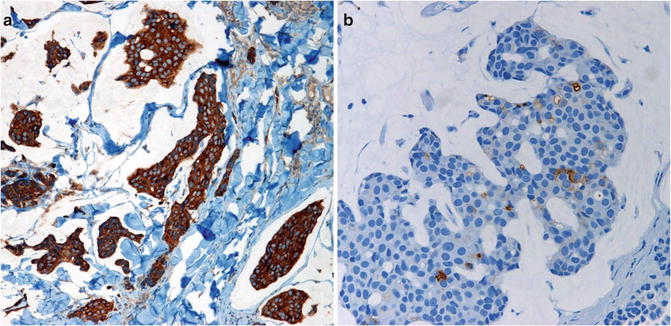

Fig. 28.1

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Multiple solid lobules showing areas of cribriform architecture, duct-like structures, and extracellular mucin production

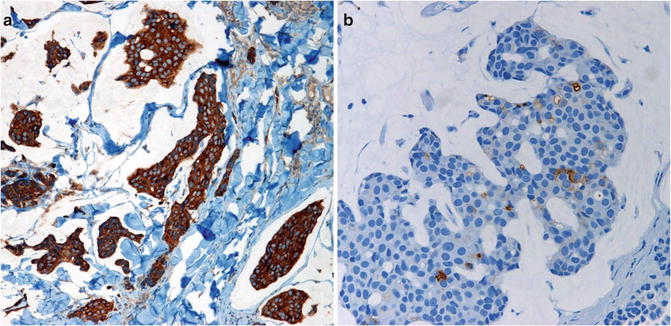

To diagnose EMPSGC, the expression of specific neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin or synaptophysin is required (Fig. 28.2). Furthermore, the tumor cells are positive for neuron-specific enolase (NSE), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CK7, gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15), and the estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors. The demonstration of a peripheral layer of myoepithelial cells with calponin, p63, and CD10 plays in favor of an in situ rather than invasive carcinoma, while lack of identification of individual myoepithelial cells supports the invasive nature of the tumor.

Fig. 28.2

(a). The tumor cells are strongly positive for synaptophysin and (b) focally for chromogranin

Differential Diagnosis

The immunohistochemical profile along with the histological resemblance to breast carcinoma makes it crucial to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastases in all cases. Moreover, EMPSGC should be differentiated from other adnexal neoplasms like hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Given its basaloid nature, EMPSGC may also be confused with an unusual nodular basal cell carcinoma. Positive staining with neuroendocrine markers can conclusively distinguish EMPS from similar adnexal neoplasms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree