Nasal reconstruction is one of the most challenging aspects of facial plastic surgery. The authors present reconstructive techniques to maximize the final aesthetic result and minimize scarring. They discuss techniques used in nasal reconstruction with a paramedian forehead flap (PMFF) that help to achieve these goals and minimize the chance of complications, including performing a surgical delay, using generous, supportive cartilage grafts, adding extra length and bulk to the flap at the alar rim and using topical nitroglycerin and triamcinolone injections when indicated. The steps outlined can help to create a more elegant and consistent result in PMFF nasal reconstruction.

Elegant solutions are frequently sought by both artists and engineers. In dance, for example, elegance is defined by the minimum amount of motion that results in the maximum visual effect. Similarly, engineers strive to provide simple and practical solutions to their challenges while efficiently balancing the demands of time, materials, and other constraints. The confluence of art and engineering is never more intertwined than it is in complex multistage nasal reconstruction. The surgeon must draw on both the practical and scientific qualities of an engineer and the creativity of an artist. Experienced surgeons can quickly identify challenges, craft efficient solutions, and optimize reconstructive benefits for their patients with each surgery. In short, experienced surgeons reconstruct complex nasal defects with the most elegant of solutions.

The basic principles and techniques of facial reconstruction have been in use and relatively unchanged for a surprising number of years. As early as the fourth century, a Byzantine physician named Oribasius described advancement flaps, recognized the importance of tension-free closure, and warned of complications in poor wound healers, the elderly, and individuals in generally poor health. Because the human eye can perceive asymmetries of only millimeters, the modern facial plastic surgeon must be creative and precise to recreate facial symmetry as much as is humanly possible.

In evaluating a patient for facial reconstructive surgery, the reconstructive ladder of increasing complexity and surgical involvement must always be discussed and patients must be guided to the surgical option that best suits their needs and goals. A skin defect can be closed primarily, allowed to heal by secondary intention, repaired with a split or full-thickness skin graft, or reconstructed with a local, regional, or free flap. This article describes refinements in the technique of paramedian forehead flap (PMFF) nasal reconstruction by the senior author (SRM) over his years of practice in a university setting.

Preoperative planning

There are several factors to consider before initiating any discussion of reconstructive options for a specific patient. In patients undergoing Mohs surgery, the margins should be pathologically clear before reconstruction. If there is a significant risk of recurrence, methods of reconstruction may be suggested that allow for easy monitoring, such as skin grafting. In such a case, a more cosmetically acceptable definitive reconstruction can be deferred to a later date.

Certain patient populations have poor peripheral circulation, putting them at risk for flap necrosis. Risk factors that cause endothelial dysfunction and impaired neoangiogenesis include tobacco use, poorly controlled diabetes, and irradiation. Tobacco use, in particular, increases the risk of flap necrosis and skin slough, and this has been well documented in patients who have undergone rhytidectomy. A study in patients undergoing breast reconstruction with a transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap suggests the results are best when a patient abstains from smoking for at least 4 weeks both preoperatively and postoperatively. We also advise our patients to abstain from smoking for a minimum of 4 weeks both preoperatively and postoperatively. However, because many Mohs reconstructions present with little forewarning, the smoking status of the patient must be factored into a safe reconstructive plan, with the performance of a delayed PMFF often the method of choice in a patient who smokes.

The delay phenomenon

The practice of surgical delay improving a flap’s viability has long been noted. Surgical delay seems to cause several mostly transient effects, including division of sympathetic nerves causing initial release and then depletion of adrenergic factors from nerve endings, vasodilation occurring parallel to the long axis of the flap, ischemic conditioning, blunted release of vasoconstrictive metabolites, and, later, neoangiogenesis. Animal studies have reported maximally increased blood flow at the distal ends of random pattern flaps in as few as 4 days and lasting as long as 14 days. Most relevant human studies have investigated breast reconstruction and generally endorse best results with a delay of 7 to 14 days. We currently recommend a delay of 7 to 10 days and have a low threshold to perform a delay stage before reconstruction for at-risk patients. It is often difficult for both the surgeon and the patient to commit to surgical delay because of the additional stage of reconstruction that is required. However, we strongly believe that the addition of a delay stage before a given reconstruction can significantly decrease the chances of a flap-related complication. As otolaryngologists, many of us were taught, “If you think of a tracheotomy, perform a tracheotomy”; as facial plastic surgeons, we offer the perspective, “If you think of a delay stage, perform a delay stage.” The additional cost of a delay stage is worth the prevention of distal flap necrosis and the multiple surgeries often required for its repair.

The delay phenomenon

The practice of surgical delay improving a flap’s viability has long been noted. Surgical delay seems to cause several mostly transient effects, including division of sympathetic nerves causing initial release and then depletion of adrenergic factors from nerve endings, vasodilation occurring parallel to the long axis of the flap, ischemic conditioning, blunted release of vasoconstrictive metabolites, and, later, neoangiogenesis. Animal studies have reported maximally increased blood flow at the distal ends of random pattern flaps in as few as 4 days and lasting as long as 14 days. Most relevant human studies have investigated breast reconstruction and generally endorse best results with a delay of 7 to 14 days. We currently recommend a delay of 7 to 10 days and have a low threshold to perform a delay stage before reconstruction for at-risk patients. It is often difficult for both the surgeon and the patient to commit to surgical delay because of the additional stage of reconstruction that is required. However, we strongly believe that the addition of a delay stage before a given reconstruction can significantly decrease the chances of a flap-related complication. As otolaryngologists, many of us were taught, “If you think of a tracheotomy, perform a tracheotomy”; as facial plastic surgeons, we offer the perspective, “If you think of a delay stage, perform a delay stage.” The additional cost of a delay stage is worth the prevention of distal flap necrosis and the multiple surgeries often required for its repair.

Surgical technique

General Principles

It is important to think of the face in terms of aesthetic subunits and to approach each reconstruction with these in mind. As much as possible, incisions should be placed at the borders of aesthetic subunits where they are least noticeable. Generally, a scar within a subunit is more obvious than a scar located at a border between subunits. As a result, the best reconstruction may involve removing additional tissue and rebuilding an entire subunit if the defect involves 50% or more of that subunit. However, there are some exceptions, and a blind adherence to the 50% rule should be no substitute for an artistic reconstructive eye. For example, with lighter skin color, such as Fitzpatrick type I or II, a scar may be placed across a subunit without being noticed as much as with darker skin color. In addition, in contrast to thinner nasal skin, thicker sebaceous nasal skin can be a poor match with the forehead. In this situation, a PMFF might not be the best choice for reconstruction, and one may wish to avoid excising the remaining portion of a subunit if it would make the difference in requiring a pedicled flap for coverage.

PMFF

The PMFF is extremely useful for nasal defects with a diameter larger than 1.5 cm because it can provide a significant amount of nasal coverage with minimal donor defect and is usually an ideal color match for the nose. The flap is centered on the supratrochlear vessels at the medial canthus and should be about 1.2 cm in width at its base. A foil template should be created to match the defect and outlined at the forehead with adequate length to reach the defect in a tension-free manner. The flap can then be elevated and inset. The pedicle can be safely divided and inset 3 weeks later. For full-thickness defects that involve the intranasal lining, the PMFF can be folded over to close the intranasal defect as an alternative to full-thickness skin grafting or a mucosal flap. In this situation, a 3-stage operation can be performed at 3-week intervals with delayed placement of a large auricular cartilage batten graft in stage 2. A large cartilage graft, preferably from the septum, abutting the nasal sidewall is often used to provide extra support and prevent collapse.

Surgical Instrumentation

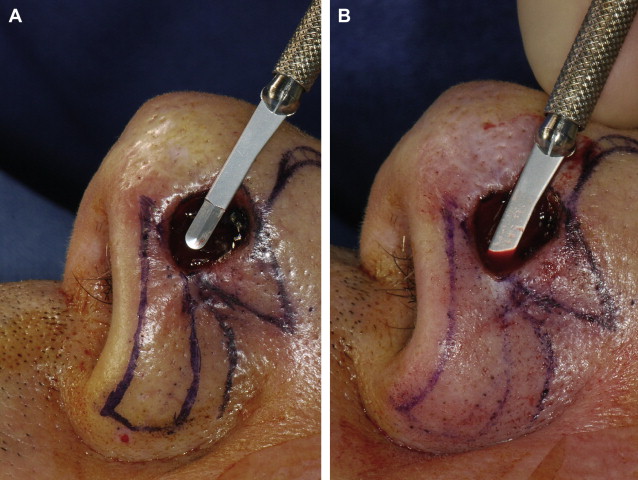

In our experience, the 6900 Beaver blade (Becton, Dickinson and Company (C), Waltham, MA, USA) is a very useful instrument for soft tissue reconstruction of the face and has several applications in PMFF surgery. Unlike the more common 11 and 15 blades, the 6900 Beaver blade is not as widely used. Surgeons who may not be familiar with this particular blade are encouraged to experiment with its use. In soft tissue work, the surgeon can stab into the tissue similar to using an 11 blade. The 6900 Beaver blade, however, is narrower and allows for the creation of precisely sized pockets for the cartilage grafts often used in PMFF nasal reconstruction. In addition, the 6900 Beaver blade is similar in feel to the 15C blade with the added advantage of being able to cut in all directions. Because the 6900 Beaver blade cuts on all sides, it does not need to be continually reinserted when creating a cartilage graft pocket, thereby promoting operative efficiency. The qualities of this blade allow the surgeon to hold it much like a pencil or paintbrush and paint through the soft tissue with artistic precision, cutting with both forward and backward strokes as well as delicate stabbing advancements. We have found this blade particularly helpful in creating tight pockets to receive the alar rim grafts commonly used in PMFF surgery ( Fig. 1 ).

The 6900 Beaver blade is also an excellent instrument for thinning flaps, which is important for achieving a well-contoured final result. The senior author (SRM) originally thinned flaps after their elevation from the forehead using sharp serrated scissors. However, we have found it more efficient to thin the PMFF as it is initially raised from the forehead. In this situation, as the flap is being raised off the frontalis musculature, there is extra tension along the flap that, combined with the 6900 Beaver blade, provides an excellent opportunity for flap thinning as it is initially raised. In this technique, the perimeter of the flap is created with either 11 or 15C blade scalpels. Small double-pronged skin hooks are then placed along the edge of the flap for upward tension while the surgeon sits at the head of the bed with the patient’s forehead positioned such that both the surface and the immediate underside of the flap can easily be viewed with a simple shift of the surgeon’s gaze. In this manner, the 6900 Beaver blade is gently stabbed into the tissue, leaving 1 to 3 mm of subcutaneous fat on the underside of the forehead flap. The surgeon can watch from below as the blade precisely enters the subcutaneous fat layer and then watch the skin surface of the flap as the blade causes the skin to gently rise, similar to what is seen when the tips of a face-lift scissor press on the underside of the cheek skin during wide undermining. The ability to paint this blade back and forth while gently advancing has allowed us to safely and more quickly raise nicely thinned flaps. These thinner flaps eventually result in a superior contour match. Another advantage of this technique is that subcutaneous fat and frontalis muscle are left in place at the patient’s forehead, which can more quickly provide a healthy base of living tissue on which granulation tissue can more quickly form when the forehead defect cannot be closed primarily and must heal by secondary intention.

Achieving Alar Rim Symmetry, Skin Layer

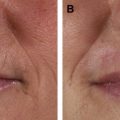

In PMFF reconstruction of the alar subunit, alar retraction is a significant complication that the facial plastic surgeon must work diligently to prevent. In one published study, alar retraction was reported to occur as often as 40% of the time after alar rim reconstruction. Even subtle alar retraction can significantly reduce the elegance of the final surgical result.

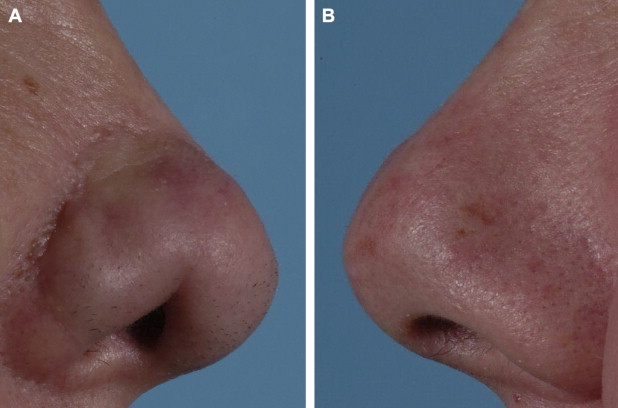

Achieving symmetric alar rims is made all the more difficult when a full-thickness defect that involves the alar rim must be repaired. The classic teaching for PMFF nasal subunit reconstruction has been to create a flap that exactly replaces the tissue and/or subunit that has been removed. Through a busy PMFF reconstruction practice dealing with many full-thickness defects, the senior author (SRM) prefers to use a folded PMFF for most of his full-thickness alar subunit reconstructions and has learned that it is often advantageous to leave an additional 2 to 3 mm of tissue at what will eventually be the alar rim. Leaving this tissue is particularly important when reconstructing the ala of someone with a very high aesthetic standard. The reasoning for this is that during the course of a multistage full-thickness alar subunit reconstruction, the distal part of the flap, which will be the new alar rim, is the part of the flap most vulnerable to distal ischemia and poor wound healing. If classic design of the skin paddle is followed and an exact amount of replacement skin is brought from the forehead to the missing alar subunit, the symmetry of the final reconstruction will be in serious jeopardy if there is any distal flap necrosis resulting in a paucity of tissue at the alar rim ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). It is extremely difficult to add an additional 2 to 3 mm of tissue once it has been lost, and the patient can expect multiple additional operations in an effort to reconstruct the missing tissue at the alar rim.

A more elegant solution, however, is to purposefully leave 2 to 3 mm of tissue in the skin paddle in the area of the paddle that will eventually be the alar rim. One can always debulk the alar rim to create near-perfect symmetry, but it is another matter altogether to build it up if there is tissue loss and the rim retracts.

Achieving Alar Rim Symmetry, Cartilage Layer

As the sixteenth century French physician Francois Rabelais once said, “Nature abhors a vacuum.” There are many situations in facial reconstruction for which this tenet rings true and perhaps none quite as much as when attempting to reconstruct an alar rim. The nasal ala is actually devoid of cartilage in its lateral inferior region ( Fig. 4 ). When a partial or full-thickness defect is present in this area, it is important to reconstruct the area with generously sized alar rim grafts. More importantly, when these grafts are inset along the lateral nasal sidewall, it is imperative that there are no soft tissue gaps between abutting edges of cartilage grafts ( Fig. 5 ). If gaps are left between adjacent cartilage grafts, the sidewall can contract, obliterating the dead space and leaving behind a retracted nasal ala.