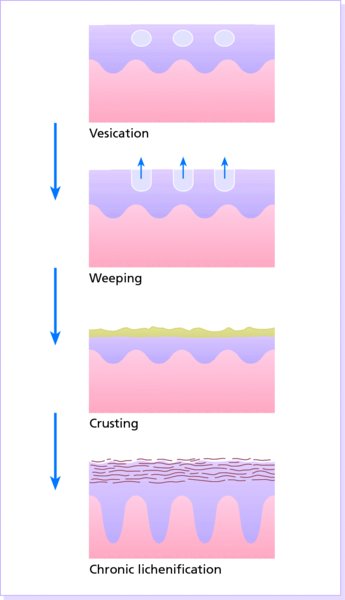

7 The disorders grouped under this heading are the most common skin conditions seen by family doctors, and make up some 20% of all new patients referred to our clinics. The eczemas are a disparate group of diseases, but unified by the presence of itch and in the acute stages, of oedema (spongiosis) in the epidermis. In early disease the stratum corneum remains intact, so the eczema appears as a red smooth oedematous plaque. With worsening disease the oedema becomes more severe, tense blisters appear on the plaques, or they may weep plasma. If less severe or if the eczema becomes chronic, scaling and epithelial disruption occurs, giving chronic eczemas a characteristic appearance. All these are phases of the reaction pattern are known as eczema. The word eczema comes from the Greek for ‘boiling’ – a reference to the tiny vesicles (bubbles) that are often seen in the early acute stages of the disorder, but less often in its later chronic stages. Dermatitis means inflammation of the skin and is therefore, strictly speaking, a broader term than eczema – which is just one of several possible types of skin inflammation. To further complicate matters, the classification of eczemas is a messy legacy from a time when little was known about the subject. Some are given names based on etiology, for example irritant contact dermatitis, and venous eczema. Others are based on the appearance of lesions (e.g. discoid eczema and hyperkeratotic eczema), while still others are classified by site (e.g. flexural eczema and hand eczema) or age (e.g. infantile eczema and senile eczema). These classifications invite overlap. However, until the causes of all eczemas are clear, both students and dermatologists are stuck with the time-honoured, yet muddled, nomenclature (Table 7.1) that we use here. Table 7.1 Eczema: a working classification. A rational subdivision of dermatitis into exogenous (or contact) and endogenous (or constitutional) types has recently been formalized by the World Allergy Organization into the classification shown in Table 7.2 although this is not widely used. Table 7.2 Dermatitis: World Allergy Organization classification. Inflammation is the hallmark of all eczemas. The skin is a large and complex organ and exposed to all the existential hazards of the environment. Unsuprisingly, there has evolved a sophisticated array of innate and acquired immune defences. Different challenges will produce different responses and types of eczema, described in more detail below. Common to all eczemas is an interaction between precipitating factors, keratinocytes and T lymphocyes. In allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) an initial exposure to an allergen, involves antigen-processing Langerhans and dermal dendritic cells carrying the antigen to the regional lymph nodes and presenting it to naïve T cells. On subsequent exposure, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are activated and release Th1 cytokines including γ-interferon (IFN-γ). These T cells express Fas ligand on their surface and release the cytotoxins perforin and granzyme-B. Simultaneously, and stimulated by IFN-γ exposure, keratinocytes express Fas, major histocompatibility complex Class II (MHC-II) molecules and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) on their surface. This potent combination of factors leads to keratinocyte apoptosis, spongiosis and further chemokine release which perpetuates the infiltration of inflammatory cells. In atopic eczema, skin barrier defects (p. 10) probably allow enhanced allergen penetrations. In contrast to ACD, CD4+ helper T cells predominate, displaying a Th2 profile of cytokine release in acute lesions, but progressing to Th2 with time. Ultimately, similar histological changes are seen in the skin of atopic patients as in allergic and irritant eczemas. The clinical appearance of the different stages of eczema mirrors their histology. In the acute stage, oedema in the epidermis (spongiosis) progresses to the formation of intraepidermal vesicles, which may coalesce into larger blisters or rupture. The chronic stages of eczema show less spongiosis and vesication but more thickening of the prickle cell layer (acanthosis) and horny layers (hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis). These changes are accompanied by a variable degree of vasodilatation and infiltration with lymphocytes. The different types of eczema have their own distinguishing marks, and these will be dealt with later; most share certain general features, which it is convenient to consider here. The absence of a sharp margin is a particularly important feature that separates eczema from most papulosquamous eruptions. Other distinguishing features are epithelial disruption (Figure 7.1) shown by coalescing vesicles, bullae and oedematous papules on pink plaques, and a tendency for intense itching. Figure 7.1 The sequence of histological events in eczema. Acute eczema (Figures 7.2 and 7.3) is recognized by: Figure 7.2 Acute vesicular contact eczema of the hand. Figure 7.3 Vesicular and crusted contact eczema of the face (cosmetic allergy). Chronic eczema may show all of the above changes but is, in general: More likely to show lichenification (Figures 7.4 and 7.5) – a dry leathery thickened state, with increased skin markings, secondary to repeated scratching or rubbing; and Figure 7.4 Lichenification of the wrists – note also the increased skin markings on the palms (atopic palms). Figure 7.5 Stretch marks following the use of too potent topical steroids to the groin. Heavy bacterial colonization is common in all types of eczema but overt infection is most troublesome in the seborrhoeic, nummular and atopic types. Local superimposed allergic reactions to medicaments can provoke dissemination, especially in gravitational eczema. All severe forms of eczema have a huge effect on the quality of life. An itchy sleepless child can wreck family life. Eczema can interfere with work, sporting activities and sex lives. Jobs can be lost through it. This falls into two halves. First, eczema has to be separated from other skin conditions that look like it. Table 7.3 plots a way through this maze. Always remember that eczemas are scaly, with poorly defined margins. They also exhibit features of epidermal disruption such as weeping, crust, excoriation, fissures and yellow scale (due to plasma coating the scale). Papulosquamous dermatoses, such as psoriasis or lichen planus are sharply defined and show no signs of epidermal disruption. Table 7.3 Is the rash eczematous? Occasionally a biopsy is helpful in confirming a diagnosis of eczema, but it will not determine the cause or type. Once the diagnosis of eczema becomes solid, look for clinical pointers towards an external cause. This determines both the need for investigations and the best line of treatment. Sometimes an eruption will follow one of the well-known patterns of eczema, such as the way atopic eczema picks out the skin behind the knees, and a diagnosis can then be made readily enough. Often, however, this is not the case, and the history then becomes especially important. A contact element is likely if: Each pattern of eczema needs a different line of enquiry. Exogenous eczemas can be irritant or allergic. They are diagnosed predominantly on the distribution, which suggests contact with a precipitating factor. Irritant eczemas are a result of agents that produce keratinocyte damage without immunological memory. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV delayed type hypersensitivity reaction involving sensitization and then elicitation. Thus, the main decision when investigating an exogenous eczema is whether to undertake patch testing (p. 38) to confirm allergic contact dermatitis and to identify the allergens responsible. In patch testing, standardized non-irritating concentrations of common allergens are applied to the normal skin of the back. If the patient is allergic to the allergen, eczema will develop at the site of contact after 48–96 hours. Patch testing with irritants is of no value in any type of eczema, but testing with suitably diluted allergens is essential in suspected allergic contact eczema. The technique is not easy. Its problems include separating irritant from allergic patch test reactions, and picking the right allergens to test. If legal issues depend on the results, testing should be carried out by a dermatologist who will have the standard equipment and a suitable selection of properly standardized allergens (see Figure 3.8). Patch testing can be used to confirm a suspected allergy or, by the use of a battery of common sensitizers, to discover unsuspected allergies, which then have to be assessed in the light of the history and the clinical picture. A visit to the home or workplace may help with this. Photopatch testing is more specialized and facilities are only available in a few centres. A chemical is applied to the skin for 24 hours and then the site is irradiated with a suberythema dose of ultraviolet irradiation; the patches are inspected for an eczematous reaction 48 hours later. The only indication for patch testing here is when an added contact allergic element is suspected. This is most common in gravitational eczema; neomycin, framycetin, lanolin or preservative allergy can perpetuate the condition and even trigger dissemination. Ironically, rubber gloves, so often used to protect eczematous hands, can themselves sensitize. The role of prick testing in atopic eczema is discussed on p. 39. The presence of a raised level of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies is necessary to make a diagnosis of atopic eczema under the new World Allergy Organization criteria (Table 7.2) but this information only rarely affects management and is thus not routinely carried out in our practice. If the patient also has asthma or allergic rhinitis, the test results may be misleading even though they do tend to indicate an atopic state. Total and specific IgE antibodies are measured by a fluorescence enzyme labelled test (ImmunoCAP). Prick and ImmunoCAP testing give similar results but many now prefer the more expensive ImmunoCAP test as it carries no risk of anaphylaxis, is easier to perform and is less time consuming. Although not all children with atopic eczema have elevated IgE levels, those that do are more likely to have eczema persisting into adult life, and are also more likely to develop asthma. If the eczema is worsening despite treatment, or if there is much crusting, bacterial superinfection may be present. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of an infective flare in atopic eczema and background colonisation with S. aureus is found in around 90% of patients with atopic eczema. Staphylococcal superantigen enhances Th2 responses and it also releases a number of proteases that damage the skin barrier. Treatment of S. aureus induced flares with appropriate antibiotics – usually flucloxacillin or erythromycin – helps bring the disease back under control. Scrapings for microscopical examination (p. 37) and culture for fungus will rule out tinea if there is clinical doubt – as in some cases of discoid eczema. Finally, malabsorption should be considered in otherwise unexplained widespread pigmented atypical patterns of endogenous eczema. Topical treatment of eczema relies on two components: emollients and anti-inflammatory agents. The importance of emollients has been underscored by the growing understanding of the relevance of defects in the skin barrier to the aetiology of eczema. Emollients should be used daily and in generous quantities by eczema patients. A good rule of thumb is that 10 times as much emollient should be prescribed (and used!) as corticosteroid. For chronic eczema with dry skin, emollient ointments such as soft white/liquid paraffin mix, or emulsifying ointment should be used. For acute inflammatory eczemas emollient creams such as Aveeno, Diprobase or Oilatum are preferred (Formulary 1, p. 397). Strong soaps should be avoided as they can be irritant and impair the skin barrier. Aqueous cream or emulsifying ointment can be used in their place. Aqueous cream should be avoided as a leave on emollient as it contains the detergent sodium laurel sulfate which damages the skin barrier and can worsen eczema. The inflammation of eczema needs treatment with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors. The potency of corticosteroids is graded as mild, moderate, potent and very potent (Formulary 1, p. 401) and the strength used is determined by age, body site and severity of eczema. The major side effect of corticosteroids is epidermal atrophy (Figure 7.6), but by avoiding use of too potent a steroid for too long this can be avoided. An inadequately strong preparation will not settle the eczema and should equally be avoided. Nothing stronger than 0.5 or 1% hydrocortisone ointment should be used in infancy. In adults, only mild corticosteroids, or moderately potent ones for no more than 1 week should be used for treatment of the face. On the body in adults, moderately potent or potent steroid creams will be needed. The hands and feet have a thick stratum corneum and weaker steroid creams produce little benefit. Very potent steroids should be reserved for use at these sites or for short periods of time on the body when severe eczema is difficult to bring under control. Corticosteroids should be applied once daily to eczema, increasing to twice daily if it fails to improve. The quantities needed for once daily application to different body sites are shown in Table 26.4 (p. 364). If patients are suffering from more than three or four flares of eczema per year, a good trick is to apply corticosteroids to previously affected body sites on two days of the week during remissions. This reduces the number of flares of eczema and thus overall long-term steroid use and such twice weekly steroid application is unlikely to induce atrophy. Emollients should be used at least twice daily, and this should continue during remissions. Figure 7.6 Licking the lips as a nervous habit has caused this characteristic pattern of dry fissured irritant eczema. The topical calcineurin inhibitors pimecrolimus and tacrolimus have the advantage of not inducing skin atrophy. Tacrolimus (Formulary 1, p. 403) is a macrolide immunosuppressant produced by a streptomycete. The anti-inflammatory actions of 0.1% tacrolimus are similar to a potent corticosteroid. Pimecrolimus (Formulary 1, p. 403) is another topical immunosuppressant and a derivative of askamycin, but has less anti-inflammatory actions than moderate topical corticosteroids. Tacrolimus is particularly useful in adult patients with facial eczema which is failing to respond do mild or moderate corticosteroids and can also be used in eczema on the body where long-term potent corticosteroids would be needed to maintain control. Pimecrolimus and.03% tacrolimus can be used in children. As with corticosteroids, twice weekly use of tacrolimus during periods of remission extends the time to relapse. Patients should be advised to avoid excessive exposure to sunlight or UV lamps while using tacrolimus. If topical treatment fails to control eczema, systemic treatment or phototherapy may be needed. Short courses of systemic steroids can occasionally be justified in extremely acute and severe eczema, particularly when the cause is known and already eliminated (e.g. allergic contact dermatitis from a plant such as poison ivy). However, prolonged systemic steroid treatment should be avoided in chronic cases, particularly in atopic eczema. Hydroxyzine, doxepin, alimemazine and other antihistamines (Formulary 2, p. 415) may help at night. Systemic antibiotics may be needed in widespread bacterial superinfection. Staphylococcus aureus routinely colonizes all weeping eczemas and most dry ones as well. Simply isolating it does not automatically prompt a prescription for an antibiotic, although if the density of organisms is high, usually manifest as extensive crusting, then systemic antibiotics can help. For longer term systemic management, patients with moderate to severe eczema can benefit from the purine analogue azathioprine (Formulary 2. p. 418). Relatively common polymorphisms in the gene coding for thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) lead to low or absent levels of this azathioprine metabolizing enzyme. TPMT levels must thus be checked before starting azathioprine to determine in whom the drug must be avoided because of absent activity, and in whom lower doses should be given because of low activity. Severe and unresponsive cases may be helped by short courses of ciclosporin under specialist supervision (Formulary 2, p. 418). Short (6-week) courses may induce long-term remission in adults, but in children continuous therapy is usually needed. For chronic hand eczema that is not responding to potent topical corticosteroids, alitretinoin is the only licensed systemic treatment. It clears hand eczema in almost half of patients, but should be discontinued if there has been no improvement after the first 12 weeks of treatment. Like all systemic retinoids it is highly teratogenic and should be prescribed with great caution in women of childbearing years. Phototherapy with UVB, or narrowband UVB is effective for widespread eczema. For hand or foot eczema, local PUVA can be given (see Chapter 27). This does best with rest and liquid applications. Non-steroidal preparations are helpful and the techniques used will vary with the facilities available and the site of the lesions. In general practice, a simple and convenient way of dealing with weeping eczema of the hands or feet is to use thrice daily 10-minute soaks in a cool 0.65% aluminium acetate solution (Formulary 1, p. 398) – saline or even tap water will do almost as well – each soaking being followed by a smear of a corticosteroid cream and the application of a non-stick dressing or cotton gloves. One reason for dropping the dilute potassium permanganate solution that was once so popular is because it stains the skin and nails brown. Wider areas on the trunk respond well to corticosteroid creams. However, traditional remedies such as exposure and frequent applications of calamine lotion, and the use of half-strength magenta paint for the flexures are also effective. An experienced doctor or nurse can teach patients how to use wet dressings, and supervise this. The aluminium acetate solution, saline or water can be applied on cotton gauze, under a polythene covering, and changed twice daily. Details of wet wrap techniques are given below. Rest at home will help too. This is a labour-intensive but highly effective technique, of value in the treatment of troublesome atopic eczema in children. After a bath, a corticosteroid is applied to the skin and then covered with two layers of tubular dressing – the inner layer already soaked in warm water, the outer layer being applied dry. Cotton pyjamas or a T-shirt can be used to cover these, and the dressings can then be left in place for several hours. The corticosteroid may be one that is rapidly metabolized after systemic absorption such as a beclometasone diproprionate ointment diluted to 0.025%. Alternatives include 1% or 2.5% hydrocortisone cream for children and 0.025% or 0.1% triamcinolone cream for adults. The bandages can be washed and reused. The evaporation of fluid from the bandages cools the skin and provides rapid relief of itching. With improvement, the frequency of the dressings can be cut down and a moisturizer can be substituted for the corticosteroid. Parents can be taught the technique by a trained nurse, who must follow up treatment closely. Parents easily learn how to modify the technique to suit the needs of their own child. Side effects seem to be minimal. Steroid lotions or creams are the mainstay of treatment; their strength is determined by the severity of the attack. The yellow crust and yellow scales suggest impetigo, and Staphylococcus aureus

Eczema and Dermatitis

Terminology

Mainly caused by exogenous (contact) factors

Irritant

Allergic

Photodermatitis (see Chapter 18)

Other types of eczema

Atopic

Seborrhoeic

Discoid (nummular)

Pompholyx

Gravitational (venous, stasis)

Asteatotic

Neurodermatitis

Juvenile plantar dermatosis

Napkin (diaper) dermatitis

Eczema

Atopic

Non-atopic

Contact dermatitis

Allergic

Non-allergic (irritant)

Other types of dermatitis

e.g. nummular, photosensitive, seborrhoeic

Pathogenesis

Histology

Clinical appearance

Acute eczema

Chronic eczema

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Atypical physical signs? Could be eczema but consider other erythematosquamous eruptions.

↓

Sharply marginated, strong colour, very scaly? Points of elbows and knees involved?

↓No

Yes

→

Likely to be psoriasis (see Chapter 5)

→

Can be confused with seborrhoeic eczema and neurodermatitis on the scalp, with seborrhoeic eczema in the flexures and discoid eczema on the limbs. Look for confirmatory nail and joint changes. Ask about family history.

Itchy social contacts? Face spared? Burrows found? Genitals and nipples affected?

↓No

Yes

→

This is scabies (p. 253)

→

Ensure all contacts are treated adequately – whether itchy or not.

Mouth lesions? Violaceous tinge? Shiny flat topped papules?

↓No

Yes

→

Could be lichen planus (p. 69)

→

Also consider lichenoid drug eruptions.

Annular lesions with active scaly edges?

↓No

Yes

→

Probably a fungal infection (see Chapter 16

→

More likely if the rash affects the groin, or is asymmetrical, perhaps affecting the palm of one hand only; and not doing well with topical steroids. Look at scales, cleared with potassium hydroxide, under a microscope or send scrapings to mycology laboratory. Check for contact with animals and for thickened toe nails.

Localized to palms and soles? Obvious pustules?

↓No

Yes

→

Probably palmoplantar pustulosis (p. 56)

→

Expect poor response to most topical treatments.

Unusually swollen; on the face?

↓No

Yes

→

Consider angioedema (p. 99) or erysipelas (p. 217)

→

Needs rapid treatment with antihistamines or antibiotics.

Consider dermatitis herpetiformis, not the various pityriases (rosea, versicolor and rubra pilaris) and drug eruptions (see Chapter 25).

Yes

→

Investigations

Exogenous eczema

Other types of eczema

Treatment

Topical treatment

Systemic treatment

Acute weeping eczema

Wet wrap dressings

Subacute eczema

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree