| Lower eyelid ectropion |

| Eversion of the eyelid margin |

| Horizontal lower eyelid laxity |

| Keratinization of the palpebral conjunctiva |

| Epiphora and foreign body sensation secondary to ectropion |

| Lower eyelid snap back test |

| Lower eyelid distraction test |

| Finger test to manually tighten eyelid – look at puncta for inversion |

| Orbicularis tone |

| Assess for anterior lamellar shortage to determine need for skin graft |

| Prior eyelid, facial surgery or trauma |

| Assess for co-existent lacrimal duct obstruction |

| Evaluation for negative vector |

Introduction

Eversion of the lower eyelid margin occurs as a spectrum, first starting with punctal ectropion, leading eventually to frank tarsal ectropion. Symptoms develop as the lower eyelid pulls away from the ocular surface and loses the tone required to maintain the lacrimal pump. Presenting symptoms may include tearing, foreign body sensation, ocular irritation and redness.

Several risk factors exist in the development of ectropion. First, there is an ethnic influence on the development of eyelid malposition. Asians are more prone to developing entropion than ectropion. This may be due to increased adipose in the preseptal and postseptal planes providing additional support. Second, actinic changes in the skin can cause vertical contraction leading to an increased eyelid eversion. Third, eyelid laxity leads to instability in horizontal tension, allowing vertical forces to dictate eyelid position. Disinsertion or attenuation of the lower eyelid retractors in conjunction with decreased orbicularis tone allows the eyelid to evert.

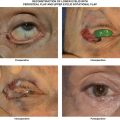

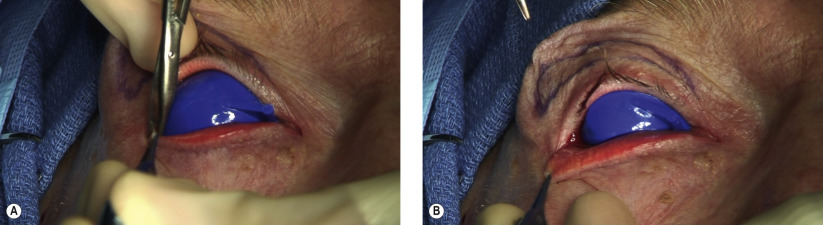

Assessment of the ectropic eyelid should focus on several factors. Eyelid laxity should be measured. Floppy eyelid syndrome should be ruled out. Anterior lamellar contraction and actinic damage may be the primary cause of eyelid eversion. If insufficient or if there is too much contraction, skin grafting may be necessary ( Chapter 27 ). Occult cutaneous malignancy should also be considered. An in-office evaluation by the physician should include manually tightening of the lower eyelid laterally and observation of the medial eyelid. If the eyelid inverts, the ectropion can likely be treated with lower eyelid tightening only. If eversion persists, tightening of the eyelid retractors will also be necessary. The globe and position of the inferior orbital rim should be evaluated to rule out a negative vector ( Chapter 10 ).

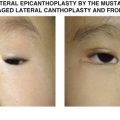

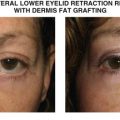

Correction of the ectropion should address components identified in the clinical evaluation. Horizontal shortening with a tarsal strip is typically required in most cases. In more severe cases, the vertical component will also need to be addressed. Transconjunctival reinsertion of the lower eyelid retractors to the inferior tarsal border is our preferred approach. With long-standing tarsal ectropion, the conjunctiva becomes redundant and a small strip can safely be excised without risk of symblepharon or fornix shortening. If a prominent negative vector is present, performing a tarsal strip may exacerbate lower eyelid retraction (pot-belly effect). In such cases, after lower eyelid retractor reinsertion, a canthoplasty that anchors the lower eyelid to the superior crus of the lateral canthal tendon instead of the lateral orbit rim will minimize this complication ( Chapter 29 ).

One final concern is the entropion that can occur after repair of long-standing ectropion. As the everted eyelid margin rests against the skin, the lashes become vertically oriented and lose their natural growth curvature outward. As the eyelid is then inverted surgically, these lashes then may abrade the cornea. With time, the natural outward growth of the lashes typically returns; however, epilation may be necessary. Eyelid margin rotation should be considered in such recalcitrant cases ( Chapters 29 , 30 , 31 ).

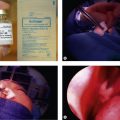

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree