Dupuytren’s Disease

Catherine M. Curtin

Dupuytren’s disease is common and surgical treatment can be very satisfying as the surgeon is able to restore function through elegant dissection of complex anatomy. There has been a recent shift in the treatment algorithm toward less invasive treatments. Despite these changes, the surgeon should determine the treatment as the anatomy remains complex and even nonsurgical interventions require a thorough understanding of the hand’s structures. In many instances, medical approaches fail and surgical intervention is required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Dupuytren’s disease is a genetic disorder, which is thought to be autosomal dominant with variable penetrance.1 Most patients are older men of European descent, and generally the disease presents in the sixth decade with a male to female ratio of approximately 3 to 1.2 The disease course and response to treatment in patients who do not fit the usual clinical picture can be very challenging. For example, patients with an earlier presentation often have a more aggressive course with high recurrence rates after surgery.3 Women generally have later onset and milder disease. However, women who require surgical intervention often have a higher incidence of postoperative pain complications.4 Beyond genetics, diabetes has been associated with the development of Dupuytren’s disease.5 Diabetic patients are another challenging subgroup because of higher rates of complications after surgery, including hematoma, delayed healing, infection, and skin sloughing.6 Understanding the average patient and those at increased risks for complications will help the surgeon counsel patients on the most appropriate treatment plan.

BASIC SCIENCE

Dupuytren’s disease is a pathologic fibroproliferative process. Although a thorough understanding of the pathologic pathways remains elusive, recent work provides insights into this disorder.7 For example, the β-catenin pathway is altered in Dupuytren’s disease and β-catenin is part of normal wound healing process.8 Also key fibroblast gene expression in people with Dupuytren’s disease is altered. Genes encoding components of the extracellular matrix are downregulated.9 These studies are the first step to the development of targeted molecular interventions.

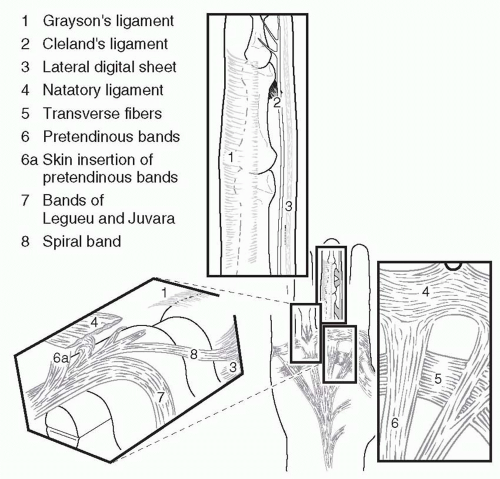

ANATOMY

Dupuytren’s disease results from deformation of normal anatomic structures (Figure 85.1). The normal anatomy is referred to as a band, whereas diseased tissue is a cord. The surgeon who treats Dupuytren’s contractures must have a thorough knowledge of the normal anatomy to release the deforming cords. In the hand with Dupuytren’s contractures, findings can range from mild skin thickening to severe flexion contractures of all of the finger joints.

Several key anatomic points are emphasized. First, the structure of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) and metacarpophalangeal joint (MPJ) impacts treatment outcomes. Metacarpophalangeal (MP) ligaments have a “cam” orientation, which means the center of rotation is eccentric relative to the ligament so that the collateral ligaments are stretched when the joint is flexed. Thus after release of the contracting cords, the collateral ligaments do not tether the joint and MPJs easily return to extension. The PIPJ is designed slightly differently. When the PIPJ is flexed the collateral ligaments and volar plate shorten and thus after Dupuytren’s release the joint may still have an intrinsic flexion contracture. Furthermore, if the proximal interphalangeals (PIPs) have been flexed for years, attempts to fully extend the joint may stretch the neurovascular structures, resulting in further damage to the finger or even loss of the digit.

A second important anatomic consideration is the relationship of the cords with the neurovascular bundles. The “spiral cord” is a continuation of the pretendinous band that merges the spiral band and the lateral digital sheet. As this cord contracts, it pulls the neurovascular bundle medial and superficial putting it at risk for injury (Figure 85.2). The surgeon who operates on a patient with Dupuytren’s disease must take care to identify and protect the neurovascular bundles.

INITIAL CONSULTATION

The initial presentation is often the beginning of a long relationship between the Dupuytren’s patient and his or her surgeon. The first step is to understand the patient’s functional status, their complaints, and goals. This will allow the surgeon to tailor the best treatment for each patient. In the history, complaints such as inability to lay a hand flat on a table should be documented as functional limitations are often used in the decision to authorize interventions.

Physical exam should include careful documentation of the degree of contracture of each finger. In addition, noting the quality of the overlying skin is crucial to help plan intervention and predict the likelihood of leaving the wound open or needing a skin graft. Finally, hand exam should also assess for concomitant issues such as carpal tunnel syndrome. In the initial consultation it is imperative that the patient understands

that the disease is part of their genetic makeup and you can only treat the symptoms and that recurrence/progression is expected.

that the disease is part of their genetic makeup and you can only treat the symptoms and that recurrence/progression is expected.

TREATMENT

No Finger Contracture/No Pain

Many patients present with a mass in the hand, skin pits, or for a feeling of “tightness” in the fingers but have no contractures. For these patients, the treatment consists of an explanation of the disease, reassurance, and clear instructions on when to consider intervention. Intervention is generally not considered until the MPJ has contracture of at least 30° or there is any contracture of the PIPJ.

Painful Palmar Nodules

Some patients with early active Dupuytren’s disease will complain of painful nodules in their palms. The conventional wisdom has been not to excise these because of the theoretical risk of flare of the disease. There is some evidence that injecting these nodules with steroids can provide some symptomatic relief and potentially soften and flatten the nodules.10

Dorsal Dupuytren’s Disease

“Knuckle pads” are generally seen in patients with a strong Dupuytren’s diathesis. These fibromatous masses on the dorsum of the PIPJs can be quite bothersome to patients but generally do not cause tethering to the extensor apparatus. The nodules can be monitored or excised depending upon the patient’s preference.

Contracted Fingers

Treatment for Dupuytren’s contractures has been evolving over the last few years. Many more options are available to the surgeon, which allows the ability to refine the approach to each cord, each hand, and each patient. The following outlines the available interventions:

1. Needle aponeurotomy (NA): This less invasive treatment for Dupuytren’s disease has been popularized in France and is gaining acceptance internationally. The premise is that the cord is weakened by percutaneous needle insertions into the cord after which the finger is manipulated to rupture the cord. Foucher reviewed 211 patients who had 261 hands treated with NA. Their study included 311 MPJs and PIPJs. The mean preoperative contracture was 65° and the mean postoperative contracture was 15°. NA was more effective for MPJs when compared with PIPJ contractures. The major complications included neuropraxia of digital nerves with one digital nerve requiring repair.11 Recurrence rate is difficult to define in Dupuytren’s research because there can be progression of old disease as well as the development of new disease. For NA, there was increased Dupuytren’s disease (both progression and new disease) in 69% of the patients at 3 years.11 Theoretically, one would expect a higher recurrence rate after these procedures given that no diseased tissue is removed, but at this time large trials assessing the recurrence after NA are lacking (Figure 85.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree