Diseases and Disorders of the Male Genitalia: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of male genital dermatoses are not known with accuracy, but most, like sexually transmitted diseases, are more common and more severe in the uncircumcised; these include psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and lichen planus (LP).1 The global prevalence of circumcision is estimated at 25%–33% and in the United States, 85%.1–5 Religious and cultural practices and medical intervention account for these rates. Circumcision has been adopted as a measure to reduce human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission.6–17 Neonatal circumcision is a topic that evokes controversy, but some benefits are accepted (Table 77-1).1,2,3,10,18–41 Although there is little evidence of significant adverse effects on health and psychosexual function, circumcision can have side effects and complications, especially when performed “ritually.”3,5,17–19,42–47 Although views of circumcision range from prophylaxis to child abuse, the rational stance is that nontherapeutic circumcision of male infants should be left to parental discretion.3,48–50

Reduced or abolished risk of penile cancer Decreased risk of cervical cancer in partners Protection from sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus infection (controversial) Reduced risk of urinary tract infections (controversial) Reduced risk of inflammatory genital skin diseases |

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Etiologic and pathogenetic factors have to be understood in relationship to structure, function, and microecology.3 Obviously the genital area differs between the sexes, but it also provides a good example of regional human variation.

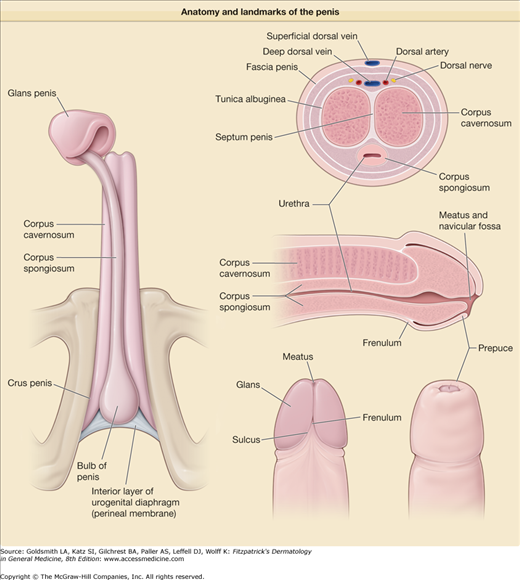

Although the whole organ of the skin is concerned with sexual expression and activity, the penis is the male structure most intimately involved in sexual intercourse. It is also the conduit for urinary excretion. The scrotum is the extracorporeal sack that maintains the testes at the ideal temperature for spermatogenesis. The essential structures of the penis and its important landmarks are illustrated in Figure 77-1.3 As at other sites, topographical and regional anatomic nomenclature is an essential part of the vernacular for a dermatologist. The anatomic position is that of full penile erection.

The perineal area is abundant in eccrine and apocrine (some functionless) sweat glands and holocrine sebaceous glands, usually in association with hair follicles as pilosebaceous units but also occurring as free glands at some sites such as the anal rim or around the coronal sulcus (Tyson glands). Adnexal secretions lubricate the hinge between limb and torso, lubricate hair, lubricate the mucocutaneous junctions to assist in the voiding of excreta, and protect the epithelia from irritation and lubricate the penis for the retraction of the foreskin during sexual activity. The pattern of keratinization differs throughout the male genital tract area, most markedly so at the mucosal junctions, the prepuce and distal penile shaft, and especially the glans in the circumcised individual. The detritus of mucosal turnover combines with adnexal secretions to produce smegma that can accumulate in the preputial sac of the uncircumcised individual, especially if hygiene is poor. There is wide normal variation in the anatomy of the penis (particularly the urethral meatus) and its relationship to the prepuce, which perhaps reflects susceptibility to minor embryologic anomalies; the embryogenesis of the anogenital structures is complex.3 The foreskin is a delicate, busy tissue that is in close contact with urine and exposed to sexual secretions, detergents, and infectious agents, especially opportunistic organisms and those that are sexually transmitted. Of the latter, human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most important known from the point of view of precancerous dermatoses and invasive squamous carcinoma. All these congenital and acquired factors can conspire to produce a dysfunctional foreskin,51 often clinically expressed as male sexual dysfunction in the form of male dyspareunia. The genitals may be a site of predilection or exclusive manifestation of disorders often encountered extragenitally (e.g., vitiligo, psoriasis, and LP), in part due to the Koebner phenomenon.3

Clinical Findings

The algorithm shown in Box 77-1 emphasizes the need to obtain a complete history, perform an adequate examination, and construct a differential diagnosis. Initiating investigations to exclude sexually transmitted disease or performing a biopsy may be indicated. Occasionally, a trial of treatment may help crystallize a diagnosis.

HISTORY | EXAMINATION | |

|---|---|---|

Age Job Symptoms Itchiness, soreness, pain Rash Lump, bump, ulcer, blister History of presenting complaint Time and space relationships, especially to sexual activity Personal and family history Circumcision Atopy Psoriasis Drugs and allergies Systemic medication Topicals Over-the-counter medication Sexual history Single/married Heterosexual/homosexual/bisexual Regular partner Last sexual activity When How (vaginal, oral, anal) Contraception Partner symptomatology Urologic history and symptomatology Smoking | Complete Mucous membranes Hair, nails, and teeth Inguinal folds and nodes Scrotum and contents Perineum and anus Prepuce Circumcised/uncircumcised Retractibility Phimosis, paraphimosis Penis Navicular fossa Glans Coronal sulcus Frenulum Shaft | Signs Pigmentary change Purpura Red patches Balanitis/posthitis/intertrigo Scaly patches Eczematous/psoriasiform/lichenoid Erosions/blisters/ulcers Papules/nodules Swelling Urinalysis DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Normal variant Sexually transmitted disease Systemic disease (e.g., diabetes) Genital manifestation of extragenital dermatosis Primary genital dermatosis Precancer (penile carcinoma in situ: PCIS) Cancer |

The responsibility for the elucidation of anogenital symptoms may need to be shared with the genitourinary physician, pediatrician, urologist, or colorectal surgeon.

Although classic dermatologic symptoms (itch, rash, lumps or bumps, or ulceration) may be present, the physician must be alert to symptoms of sexually transmitted disease (e.g., discharge, dysuria), urologic disease (e.g., pain, hematuria, dysuria), and male sexual dysfunction. Symptomatic male sexual dysfunction equates with male dyspareunia, that is, painful or difficult sexual intercourse. Many men will not volunteer such information, so specific inquiry should be tactfully made. The components of normal male sexual function are libido, erection, ejaculation, and orgasm.

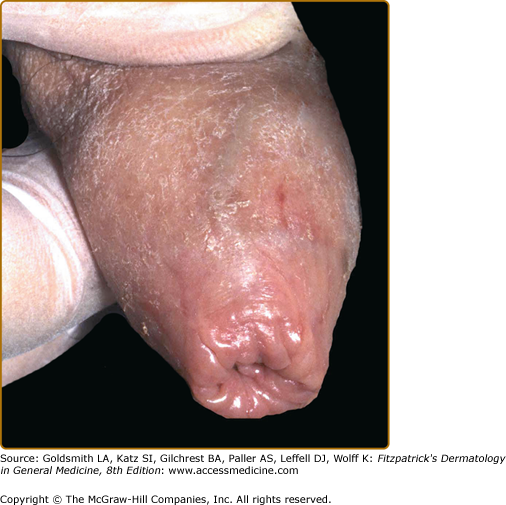

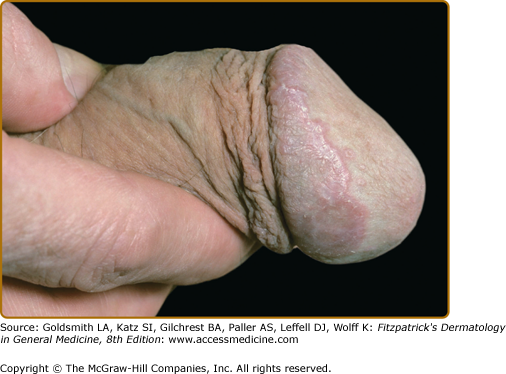

A systematic approach to the penis and prepuce is summarized in the algorithm (see Box 77-1). The foreskin (if present) should be gently retracted, the gluteal and crural folds and the meatal lips parted, and the rectum examined digitally. Site, distribution, and morphology of lesions should be conventionally noted and analyzed. Specific male genital signs include phimosis (nonretractable foreskin; Fig. 77-2), paraphimosis (foreskin fixed in retraction; Fig. 77-3), balanitis (inflammation of the glans penis), posthitis (inflammation of the prepuce), and dorsal perforation of the prepuce (glans and shaft of penis ulcerated through the prepuce, which lies ventrally as an empty sleeve). Phimosis should be regarded as a sinister situation and impedes complete inspection and palpation of the glans and coronal sulcus. The causes of phimosis are listed in Table 77-2. Paraphimosis is rarer and is usually an acute emergency presentation caused by vigorous sexual activity, acute contact urticaria, acute allergic contact dermatitis, and lichen sclerosus (LSc). Chronic paraphimosis is increasingly recognized in India and is due to chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the foreskin in the retracted state. Balanitis and posthitis xerotica (obliterans) can be confusing terms, used to signify the end stage of all chronic cases of balanitis and posthitis (e.g., scarring dermatoses such as LP and cicatricial pemphigoid), but these conditions are usually due to LSc and are therefore considered synonymous by some. Dorsal perforation of the penis is very rare and is caused by gross penile disease such as hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangrenosum, florid condylomata, chancroid, herpes simplex, idiopathic balanoposthitis, and podophyllin misuse.3,53,54

The algorithm (see Box 77-1) underlines the necessity to examine patients conventionally, systematically, and completely, because important signs will be found at nongenital sites.

Laboratory Tests

The most commonly required special investigational procedures are taking a swab or smear for microbiologic or virologic analysis, obtaining scrapings for fungal microscopic examination and culture, taking scrapings for mite identification, and performing a skin biopsy. Wood’s light examination is helpful in the clinical diagnosis of vitiligo, erythrasma, and fungal infections. The investigations pertinent to the diagnosis of sexually transmitted disease are discussed in Section 32 (see Chapters 200, 202, 203, 204 and 205).

A genital skin biopsy is informative under selected clinical conditions. It is important to obtain the right specimen from the right site at the right time (the most floridly inflamed areas may not be the best from which to obtain a specimen and histologically often show nonspecific or zoonoid features) and to provide the pathologist with a differential diagnosis. Examination of biopsy specimens should not be regarded as a substitute for clinical diagnosis. It is safe and helpful to use small amounts of adrenaline—the region is highly vascular. Knowledge of anatomy is crucial: ventrally, the urethra can lie very close to the surface in the coronal sulcus. It is not often necessary to suture a preputial punch biopsy site.3,55

Differential Diagnosis

MALE GENITAL PRURITUS | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL HYPOPIGMENTATION/LEUKODERMA/PLAQUES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL HYPERPIGMENTATION | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPOPIGMENTATION | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL POSTINFLAMMATORY HYPERPIGMENTATION | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL PURPURA | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL RED SCALY PATCHES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL RED PLAQUES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

BALANOPOSTHITIS AND INTERTRIGO | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL EROSIONS | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL VESICLES AND BLISTERS | ||

Most Likely | Consider | |

|

| |

PENILE NECROSIS | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL ULCERS | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL FLESH-COLORED PAPULES AND MICROPAPULES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL RED OR PIGMENTED PAPULES AND MICROPAPULES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL PUSTULES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL PLAQUES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL LYMPHEDEMA | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

MALE GENITAL CYSTS OR NODULES | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

PENOSCROTAL SWELLING | ||

Most Likely | Consider | Always Rule Out |

|

|

|

Normal Variants

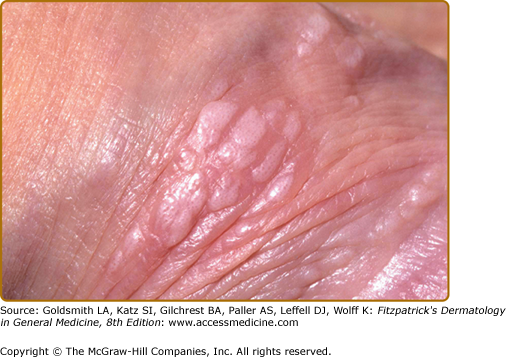

Pearly or pink penile papules,3 which may be found in between 15% and 48% of men, are flesh-colored, smooth, rounded papules (1–3 mm) occurring predominantly around the coronal margin of the glans, rarely on the glans. Often there are rows or rings of the papules. They are commoner in the uncircumcised male and regress with age.59 Ectopic lesions, for example, on the penile shaft, have been reported. They are frequently mistaken for warts or Tyson “ectopic” sebaceous glands (of Tyson) and sometimes cause anxiety in adolescents. The histologic findings are those of angiofibroma, and the lesion is analogous to other acral angiofibromas such as adenoma sebaceum, subungual and periungual fibromas, fibrous papule of the nose, acquired acral angiofibroma, and oral fibroma. Reassurance should suffice, but cryotherapy and laser treatment have been used.3

Sebaceous gland prominence, Tyson glands, sebaceous hyperplasia, and “ectopic” sebaceous glands (Fordyce condition) are all essentially equivalent, common, normal variants of the skin of the scrotal sac and penile shaft, analogous to the situation on the vermillion of the lips. Nevoid linear lesions on the penile shaft and lesions on the glans have been reported. Reassurance is usually adequate, but patients can be inordinately distressed.3

It is possible that nevi on the penis occur more frequently in patients with the atypical nevus syndrome.3 A divided or “kissing” nevus is a lesion with one-half located on the glans and the other half located on the distal penile shaft separated by uninvolved skin across the coronal divide; an analogous nevus affects the eyelids.60 Epithelioid blue nevus of the genitals is very rare.61

Prominent veins are common and very occasionally give rise to concern but very rarely cause complications.3

Angiokeratomas are more common in white men and are common on the genitalia (where, confusingly, together with prominent sebaceous glands they have attracted the eponymous epithet of Fordyce spots). Angiokeratomas are blue to purple, smooth, 2–5-mm papules on the scrotum, penile shaft, or glans. They generally appear and multiply during life but occasionally present as singletons. They may bleed after trauma and may be mistaken for a nevus, melanoma, or Kaposi sarcoma. The angiokeratomas of Fabry disease (see Chapter 136) are smaller than common angiokeratomas, presenting as less hyperkeratotic pinhead lesions, and are found more extensively around the lower limb girdle and upper thighs from the navel to the knees. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum very, very rarely may affect the penis (see Chapter 172).

Electrocautery or laser ablation can be offered, but the lesions may recur.

The complicated embryogenesis of the anogenital region involving sexual differentiation and pubertal determination of secondary sexual characteristics means that congenital and developmental anomalies are common. Consequent anatomic and functional abnormality may increase the vulnerability of the area to dermatoses (such as LSc) and infections.

Common abnormalities include meatal pit, hypospadias, median raphe cysts, canals and sinuses, and ambiguous genitalia. Rarer anomalies include hypospadias variants, meatal stricture, mucoid or urethral cysts, dermoid cysts, buried penis, urethral atresia, penoscrotal transposition, congenital lymphedema, giant preputial sac, megaprepuce, accessory scrotum, hemangiomas, strawberry nevus, os penis, and true aposthia. These entities may be features of congenital syndromes.3

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

The clinical manifestations on the male genitals of syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, gonorrhea, and other venereal diseases as well as their pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and complications are discussed in depth in Chapters 200, 202, 203, 204, and 205). Here it may suffice to remind the physician that any inflammatory, papulonodular, or ulcerative genital presentation requires consideration and exclusion of sexually transmitted diseases.

(See Chapter 208)

Pediculosis pubis, or lice infestation (“crabs”), can cause severe genital itching with few physical signs unless the hairs are examined assiduously for nits and the base of individual hairs is scrutinized with a hand lens for the crab lice (1–2 mm), which will be tightly adherent to the skin because their mouth parts are embedded in perifollicular blood vessels. Sometimes gray–blue macules (tache bleu, maculae caeruleae) are seen on the affected sites.

(See Chapter 208)

Scabies is a cause of intense itching that characteristically keeps patients awake at night. Usually there is a rash of diagnostic distribution and morphology. Some patients with scabies—who may have been infested for a long time, have had it before, have been inadequately treated, or have been adequately treated but develop secondary eczema or nodules—may have itch in the anogenital region only.

(See Chapter 196)

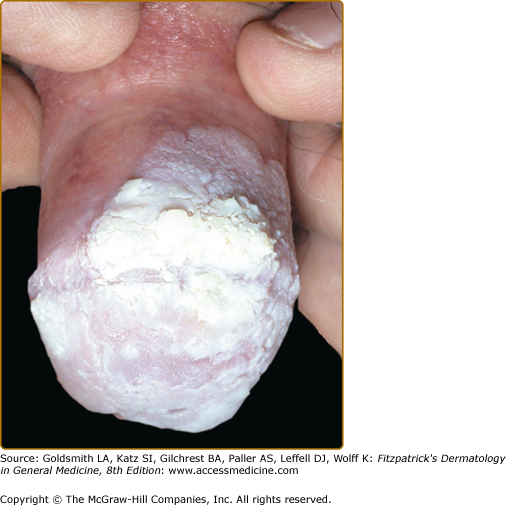

Genital HPV infection can usually be diagnosed with certainty on clinical grounds (Figs. 77-4 and 77-5). Morphology is described in Chapter 196. Clinically inapparent penile warts may present as balanoposthitis.62–64

Disorders from which viral warts must be differentiated are listed in Box 77-3.

Most Likely

|

Consider

|

Always Rule Out

|

HPV infection is a risk factor for anogenital cancer, particularly of the cervix and anus. HPV is associated with the clinical expressions of penile carcinoma in situ (PCIS), or Bowen disease of the penis, erythroplasia of Queyrat (EQ), or bowenoid papulosis (BP) and approximately 50% of cases of squamous carcinoma of the penis.65,66 Infection with HIV may alter and worsen the expression and consequences of anogenital HPV infection: high-grade dysplasia associated with high-risk HPV types have been found in the urothelium and genital warts from HIV-positive individuals and the penis cancer risk is increased three- to sixfold (the anal cancer risk may be increased by as much as 100).3,67–75

Patients presenting with warts, as well as their sexual partners, should be counseled and screened for HPV, other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV infection, and cervical neoplasia.

HPV infection may be very difficult to treat. Subclinical infection is very common, difficult to detect, and virtually untreatable, so there is divergence between ambitions for treatment and achievability. The principles of management are based on diagnosing and treating relevant lesions that are causing personal genital morbidity or psychosexual stress or long-term risk to the patient or his partner. Reasonable goals include (1) inducing cure or wart-free periods, (2) relieving or improving symptoms such as dyspareunia, (3) ensuring that side effects or complications of the treatment are no worse than the symptoms or risks of the warts, (4) minimizing morbidity and mortality from cervical cancer in female partners, (5) minimizing mortality and morbidity from PCIS and frank cancer in the patient especially those with HIV.62,69,72,73

(See Chapter 195)

Mollusca may be sexually acquired, as in adult men, but genital lesions caused by autoinoculation are common in children. Classically small, flesh-colored, monomorphic, dome-shaped papules indented by a central dell or umbilicus are seen. Multiple lesions are usually present. Giant and polypoidal lesions may occur in the setting of HIV infection. Inflammation and purulence may be due to infection but are a common phenomenon when individual lesions spontaneously involute. Condylomata lata (secondary syphilis) and LP enter the differential diagnosis of mollusca, as do simple HPV infection and BP. Treatment may not be necessary especially in children. Options are similar to those for viral warts.3,77

Dermatoses with a Predilection for the Male Genitalia

(See Chapter 74)

Vitiligo commonly affects the genitalia in men and may be the only site to be affected. Perianal involvement is also common.3 Other organ-specific autoimmune diseases should be excluded. Vitiligo has been reported after treatment of genital warts with imiquimod.78,79 An important rare differential diagnosis is depigmented extramammary Paget disease (EMPD).80 Phototherapy of vitiligo might lead to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).81

(See Chapter 22)

A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis is made when a nonspecific psoriasiform or eczematous balanitis or balanoposthitis is found in conjunction with classic symptoms and extragenital manifestations of the diathesis.3

No treatment other than reassurance may be required. However, treatments that diminish the commensal pityrosporum load and reduce irritation and eczematization can be very successfully and safely used long term. These include topical antifungals (such as clioquinol, nystatin, and imidazoles) in the form of ointments, creams, lotions, or shampoos and mixtures of the same agents with mild and moderately potent topical corticosteroids used alongside emollients and soap substitutes. In severe cases, such as with concomitant seborrheic folliculitis or in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), treatment with an oral imidazole might be indicated.

(See Chapter 18)

Psoriasis is probably the most common dermatosis of the male anogenitalia, either in isolation or in association with frank or mild, subtle extragenital disease.3 The Koebner phenomenon is a likely factor in site predilection. Drugs such as lithium, β blockers, antimalarials, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors may be responsible for the onset or exacerbation of psoriasis.

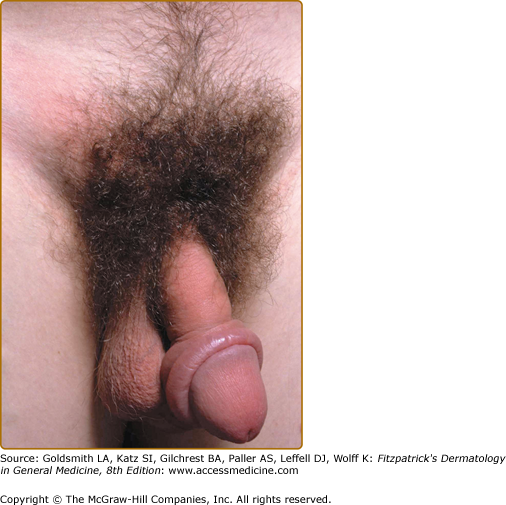

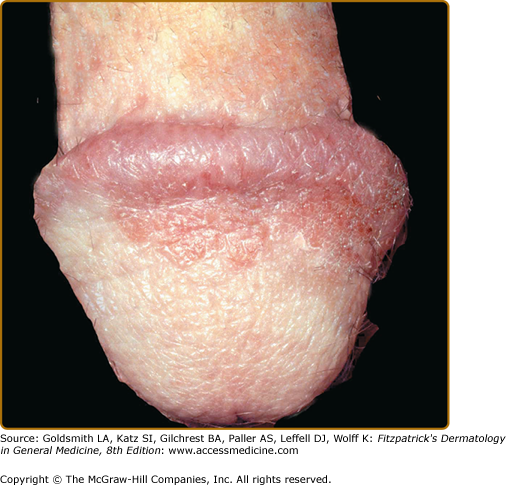

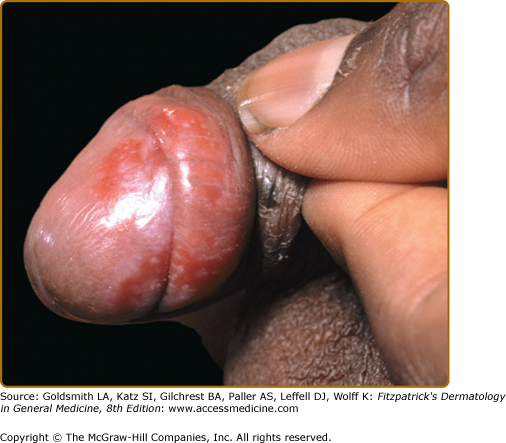

In circumcised men, genital psoriasis presents with variably itchy, silvery-scaled, erythematous patches or plaques (Fig. 77-6). On the glans or in the preputial sac of the uncircumcised patient, scale is absent from the patches or plaques because of the mucosal site (Fig. 77-7). The scalp, ears, umbilicus, and face (in sebopsoriasis) may be involved, and there may be variable additional anogenital involvement, especially of the sacrum, buttocks, intergluteal cleft, pubic mound and groin, perianal skin, and, less commonly, the scrotum. Psoriatic balanoposthitis can be part of the spectrum of inverse-pattern psoriasis and may be associated with intertriginous disease of the axillae, intergluteal cleft, gluteal folds, and groin.

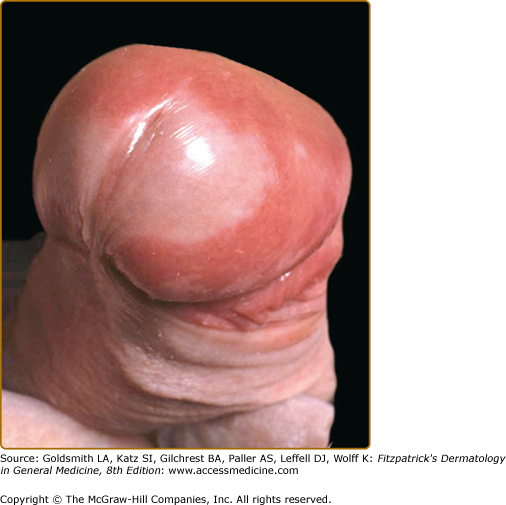

Patients with the reactive arthritis syndrome (see Chapter 20) may sometimes have involvement of the penis with circinate balanitis or small, flat pustules. These penile lesions have the same histopathology and ultrastructure as psoriasis. Sometimes this morphology is seen clinically with no background urethritis, gastroenteritis, or arthritis (Fig. 77-8).

Usually the diagnosis of psoriasis is clinical. Soreness might indicate superinfection, especially with Candida. Inordinate itch would make one suspect another dermatosis such as an eczematized dermatitis or tinea. A biopsy may be necessary if there are solitary mucosal lesions in the uncircumcised to exclude Zoon balanitis (ZB), LP, EQ, and Kaposi sarcoma. Bowen disease and EMPD may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis when there are single or several foci on the penile shaft and/or in the groin.

Topical treatment is based on the use of emollients, soap substitutes, corticosteroids combined with antibiotic and antifungal agents, or weak tar solutions. Atrophy is a risk with long-term use of potent topical steroids, and anogenital skin has a heightened tendency to absorb topical agents. Strong crude tar preparations should also therefore be avoided at this site because of the risk of genital cancer. Dithranol application may lead to burning and so is usually avoided in this region. Vitamin D analogues and calcineurin inhibitors seem safe, but with the latter, the prescriber must be certain of the absence of PCIS. Severe anogenital inverse psoriasis can be an indication for systemic treatment. Phototherapy is conventionally contraindicated because of the risk of anogenital cancer. It is possible that chronic anogenital psoriasis and its treatment may create a risk for anogenital squamous cancer.

(See Chapter 26)

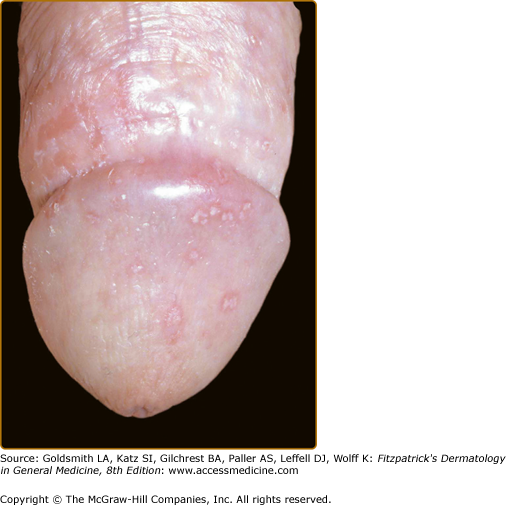

LP has a particular predilection for the mucosa, which is perhaps partly explained by the Koebner phenomenon. LP can present in, and remain focalized to, the pelvic girdle, the genital area including the groin, and the perianal skin. Alternatively, symptoms and morphology of the classic disease—lilac papules and plaques with white lacy scale—may be present at other sites (Fig. 77-9). However, it may affect the penis (like the mouth, vulva, and anus) in isolation as the cause or consequence of foreskin dysfunction (by “koebnerization”) and so present as dyspareunia and a nonspecific dermatosis.3

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, nonspecific balanoposthitis, ZB, LSc, drug eruption, porokeratosis, viral warts, penile precancer, and frank SCC. LP can cause phimosis; the differential diagnosis of phimosis is given in Table 77-2.

Just as extragenital disease, for example, on the palms and soles, may be erosive in rare cases, occasionally an erosive form of genital disease is encountered (Fig. 77-10). A male equivalent of the vulvovaginal syndrome of Hewitt with chronic erosive gingival and genital lesions (genito-gingival syndrome) has been described.82 Bullous penile LP has also been reported.83

Although LP is self-limiting, some patients experience relapses and remissions. Adhesions can form. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can persist for months or years.

Chronic mucosal erosive LP is associated with a risk of SCC, although most reports linking the two concern oral LP. SCC may complicate chronic hypertrophic LP of the lower leg but has also occurred in the context of hypertrophic LP of the glans penis.3,84,85

A biopsy is frequently necessary for diagnostic purposes but, more importantly, is performed in following up the rare cases of chronic anogenital disease in which the appearance of ulcero-erosive or verrucous features leads to concern about the development of SCC. The classic histologic findings are discussed in Chapter 114.

Potent or very potent topical corticosteroids usually produce remission. Patients should be warned about postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Systemic corticosteroids are sometimes indicated for severely symptomatic disease, erosive orogenital involvement, and scarring of the scalp and nails. Topical and systemic cyclosporin has been used. Circumcision may be necessary if there is phimosis and should be seriously considered in cases of refractory disease, especially the erosive form, because the removal of “koebnerizing” influences may allow the LP to remit. The toxicity and the lack of efficacy of systemic therapy in treating this distressingly symptomatic situation are other powerful arguments in favor of circumcision.3,86

(See Chapter 27)

Lichen nitidus is sometimes held simplistically and controversially to be a micropapular variant of LP. It has an affinity for the penis and can be difficult to diagnose because the signs may be subtle, even when the lesions are widespread. Also, when the lesions are very pruritic, the signs due to excoriation and eczematization may eclipse those due to the lichen nitidus.3

(See Chapter 44)

Erythematous smooth, ovoid nodules of granuloma affecting the penis have been described. They are perhaps related to trauma and koebnerization, because circumcision can be curative.87

Necrolytic migratory erythema can be focalized to the male genitalia as a sore or painful annular erythematous eruption with a central glassy appearance and serpiginous border surrounded by scaling. It is a characteristic cutaneous manifestation of the glucagonoma syndrome (see Chapter 153).88

The diagnosis of aphthous ulceration of the genitalia requires the exclusion of sexually transmitted diseases and other causes of genital ulceration, especially Behçet disease. This is in contradistinction to oral ulceration, in which a clinical diagnosis is acceptable practice.3 The causes of aphthae are obscure. The histologic findings of idiopathic aphthous ulceration are nonspecific. Aphthae and idiopathic orogenital ulceration are more common and are worse, symptomatically and morphologically, in HIV-infected individuals. In patients with AIDS, biopsy must be performed on all mucocutaneous ulcers and specimens must be cultured; several pathologies may coexist. Treatment of simple aphthae is with topical corticosteroid/antibiotic/anticandidal combinations. In patients with AIDS, thalidomide may be efficacious.

(See Chapter 166)

The genital ulcers in men are painful, sometimes very painful, and this distinction may be helpful. They occur anywhere on the anogenitalia, including the scrotum and perianal skin. They are said to be bigger, deeper, fewer, and less recurrent than those in the mouth.

To diagnose Behçet disease according to strict diagnostic criteria, oral ulceration must be present; then patients must also either manifest genital ulceration and ophthalmic involvement or genital ulceration and skin signs (or a positive pathergy test result). In practice, there are many patients who have an incomplete syndrome. Although their disease does not satisfy these rigid diagnostic criteria, “possible” or “probable” Behçet disease is an acceptable label for everyday practical purposes. Essentially, Behçet disease is a systemic vasculitis that may involve many organs, so that protean presentations and complications are possible. Patients with relapsing polychondritis (see Chapter 159) and Behçet disease have been reported, and the term MAGIC (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage) syndrome applied.89,90 Histologic findings are usually nonspecific and do not distinguish idiopathic aphthae, although sometimes necrotizing vasculitis can be seen. Topical treatment with corticosteroid/antimicrobial combinations may suffice. Topical interferon α lozenges have been advocated.91 However, some patients will require systemic treatment with colchicine, prednisolone, azathioprine, cyclosporin, thalidomide, infliximab, or etanercept.3,92,93 (See Chapter 166).

(See Chapter 57)

Mucous membrane (cicatricial) pemphigoid is a rare disease that must be in the differential diagnosis of blistering, erosions, ulcers, transcoronal adhesions, scarring, and phimosis.3,94 These manifestations can occur in isolation, but ophthalmic, oropharyngeal, and cutaneous lesions are more common than genital involvement. Direct immunofluorescence usually yields positive results, but indirect immunofluorescence does not. Topical and oral steroids may be ineffective. Dapsone, sulphamethoxypyridazine, mycophenolate, and biological therapies may be used.

(See Chapter 33)

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare event but is frequently misdiagnosed or diagnosed late while infections and cancer are pursued diagnostically (Fig. 77-11). It may represent a pathergic reaction after urologic surgery or complicate inflammatory bowel disease or leukemia. Treatment must be aggressive to avoid permanent damage to the urethra and erectile tissues.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree