Diseases and Disorders of the Female Genitalia: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of dermatoses affecting the female genitalia are generally not well established. The vulva has been referred to as “the forgotten pelvic organ.” Despite being the visible female genital structure, it is least described in the medical literature.1 Teaching about vulvar conditions and even the normal vulva is sadly lacking for most medical practitioners, so it is not surprising that vulvar conditions are both underreported and underdiagnosed. Approximately 16% of women report undiagnosed chronic vulvovaginal pain at some time in their lives.2,3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

The approach to the patient with vulvar complaints requires directed history taking, as outlined in Box 78-1.

|

The warm moist environment of the vulva often alters disease morphology or symptomatology. For example, usually scaling dermatoses may lack clinically obvious scale, and in diseases that usually exhibit well-demarcated plaques, the lesions may be less distinct. In addition, diseases that normally do not produce scarring of keratinized skin or oral mucosa can induce resorption of the labia minora, narrowing of the introitus, and scarring of the clitoral hood. Vulvar scarring can occur from any inflammatory condition.4

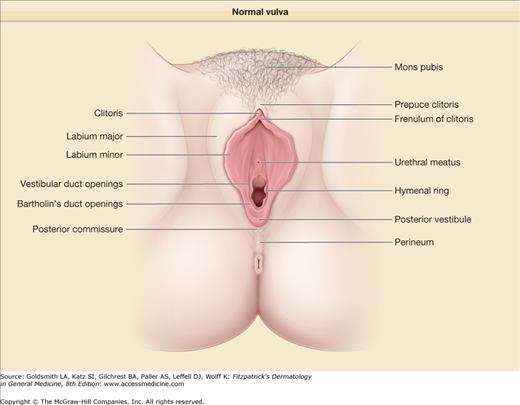

When examining the vulva, it is important to make sure there are no physical abnormalities, particularly, that all normal anatomy is present. Using a diagram can help and this also can be shared for patient education (Fig. 78-1). Unimpressive physical findings are sometimes associated with severe itching and vulvar pain. Lichenification manifested only by a slight change in texture can present with severe pruritus deserving of and responsive to aggressive therapy. Finally, a complete mucocutaneous examination is crucial, because extragenital findings can assist in the diagnosis of several genital conditions.

Skin disease affecting the vulva more often has a multifactorial etiology, compared to other areas of the body. The primary skin disease is often accompanied by and driven by a secondary yeast infection, bacterial colonization, or lack of estrogen, even in the absence of obvious clinical findings. The infection can be purely cutaneous, purely vaginal, or both. Irritant contact dermatitis from topically applied agents often exacerbates both signs and symptoms. Such contributors need to be constantly sought.

Vulvar symptoms cannot be divorced from vaginal abnormalities. Irritating or infected vaginal secretions are a common cause of vestibular (introital) symptoms, which makes a speculum examination highly advisable in many instances.

Laboratory Tests

Skin biopsy specimens for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence testing may be required. Sometimes multiple biopsy samples are required to establish a specific histologic diagnosis. When previously well-controlled dermatoses flare, repeat biopsy may be needed to rule out squamous cell carcinoma or a second disease process. When doing a vulvar biopsy, preanesthetizing the area with a topical anesthetic can be very helpful.

Culture of cutaneous swab samples, for Candida and bacteria, is indicated when concurrent infection is considered. Infection can complicate treatment at any point in the course of a disease.

A microscopic evaluation of vaginal smears allows inspection for yeast (see Chapter 189), Trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis (see Chapter 205). Abnormalities such as an increased number of white blood cells or the presence of immature epithelial cells may be seen as well and may be markers for inflammatory skin diseases, estrogen deficiency, foreign body, or pyogenic bacterial infection. Vaginal cultures, done in addition, can identify infection caused by a nonalbicans Candida organism, a pathogen difficult to see on microscopic smears but occasionally a cause of significant symptoms.

Patch testing is important if allergic contact dermatitis is suspected (see Chapter 13). Consultation with specialists in gynecology, urology, or urogynecology may be necessary to assist with diagnosis, management, or treatment. This is particularly true in the setting of multifactorial processes (e.g., incontinence as a contributing factor) or diseases requiring surgical intervention (e.g., posterior fourchette fissuring).

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the varied morphologies and frequent multifactorial presentations, the differential diagnosis of a vulvar condition can be quite broad (Box 78-2). Normal variants can be confusing as well. The diseases discussed in this chapter are grouped into the categories of inflammatory dermatoses, bullous and erosive diseases, ulcers, abscesses, and vulvodynia.

INFLAMMATORY DERMATOSES

|

BULLOUS AND EROSIVE DISEASES

|

ULCERS

|

ABSCESSES

|

Prognosis and Clinical Course

Women with vulvovaginal symptoms assume they have a curable, infectious disease. Patients need to be counseled that many genital dermatoses are controllable but not curable. These women cannot be evaluated and treated in a 10-minute office visit; they require adequate time for education and reassurance. Frequently they need to be followed long term.

Treatment

Many women are unfamiliar with their genital anatomy and do not have the vocabulary to accurately discuss their problem or follow instructions for applying topical medications. Diagrams and/or a use of a hand-held mirror are extremely helpful for patient education. The vulvar diagram (Fig. 78-1) can be very important here.

An ointment is generally the most comfortable vehicle for delivering medication to the modified mucous membranes of the vulva. Ointments spread easily, require very small volumes per application, are less sensitizing and generally cause less burning.

Irritant contact dermatitis is a common complicating factor in any genital dermatosis. Aggressive washing and use of soaps, topical medications, and home remedies are the most common offenders. Because soaps, douches, disinfectants, and very hot or cold water often are not considered relevant by patients, information regarding their use is often not volunteered, and very careful questioning is warranted. Gentle cleansing of the area can be accomplished by flushing once a day with water (or mild cleanser and water) and patting dry. Washcloths for washing and towel rubbing while drying must be avoided.

Superpotent glucocorticoids such as clobetasol propionate are often required to treat dermatoses of the female genitalia. Fortunately, glucocorticoid atrophy is surprisingly uncommon on the modified mucous membranes of the vulva. Nonetheless, patients should be reevaluated monthly during periods of daily use and warned about side effects due to spread of medication to the surrounding areas where atrophy is more likely to occur such as the inguinal crease, proximal medial thighs, and perianal skin. Limit the amount of topical steroid prescribed.

Tacrolimus or pimecrolimus can be used as steroid-sparing medications on vulvar skin. Stinging or burning frequently occurs with initial application. This is especially true for very inflamed or eroded areas. These agents are often less effective than glucocorticoids and their long-term safety is still in question. Despite these issues they are a useful second line option.5 (For efficacy and side effects, see Chapter 221.)

Warmth and moisture of the genital area are unavoidable and promote infection and maceration. Bacterial superinfection can be treated with oral antibiotics. Yeast infections are especially common, particularly when patients are treated with topical glucocorticoids and/or oral antibiotics. The identification of infection on red, scaling, and often exudative skin can be difficult and should be pursued actively in patients with recalcitrant symptoms.

Common Normal Variants

There is great variety in normal vulvovaginal anatomy. Vulvar and vaginal erythema of varying degrees is present in most asymptomatic premenopausal women, but this redness is rarely noticed before the onset of discomfort. Architecturally, the labia minora exhibit a wide range of asymmetry and sizes. Normal but very small labia minora may be difficult to differentiate from scarring produced by inflammatory skin disease. Sebaceous glands may be prominent on the inner labia minora. Harmless, soft, finger-like, skin-colored, monomorphous papules called vulvar papillomatosis can be seen around the hymenal ring. (See eFig. 78-1.1) These can be confused with genital warts.

Inflammatory Dermatoses

Clinically subtle inflammation of the vulva sometimes produces remarkable symptoms. Therefore, a very careful examination with a high index of suspicion for a dermatosis is required.

(See Chapter 15)

Vulvar lichen simplex chronicus is most often seen in atopic individuals with sensitive skin. It can complicate other vulvar dermatoses, especially contact dermatitis, lichen sclerosus and, less frequently, lichen planus.

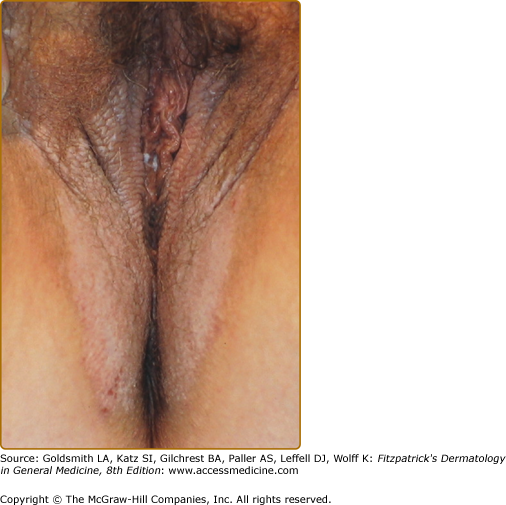

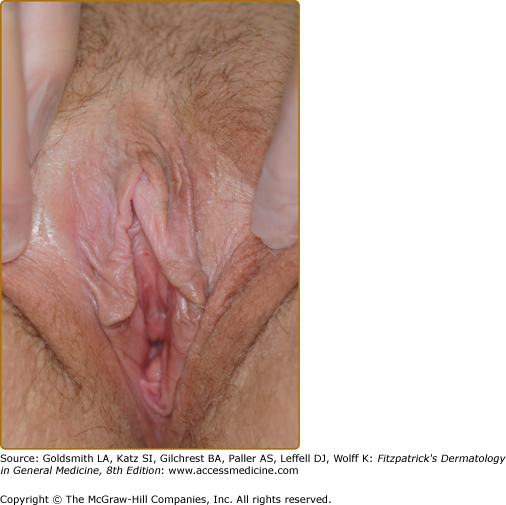

The morphologic manifestations of lichen simplex chronicus when it occurs on the vulva vary from minimal hyperpigmentation and dullness of texture of the modified mucous membranes to remarkable lichenification and edema (see Fig. 78-2 and eFigs. 78.2.1, 78.2.2, 78.2.3, 78.2.4, and 78.2.5). Erythema can be subtle on the labia majora because hair obscures the skin. Excoriations and fissures within skin folds are common but heal quickly and may not be seen in the office. Sometimes hydrated, thickened lichen simplex chronicus appears white, mimicking lichen sclerosus, or the leukoplakia of intraepithelial neoplasia.

Although the histologic findings, differential diagnosis, and therapy are similar for lichen simplex chronicus affecting the vulva as for that involving other parts of the body, there are several notable modifications.6 Contact dermatitis needs to be recognized and treated as it frequently confounds management. Women overwash and especially scrub the area and also may apply topically whatever they can find. Topical glucocorticoid therapy is a mainstay, but prompt alleviation of symptoms often requires a higher potency preparation than is standard for intertriginous skin. Those with significant lichenification do well with a superpotent preparation such as clobetasol propionate for the first few weeks. The potency or frequency can be decreased as the patient improves. Nighttime sedation is often required to interrupt the itch–scratch cycle.7 Skin and vaginal infections, often subclinical, are extremely common and often drive lichen simplex chronicus. Therefore, skin and vaginal cultures for yeast, and especially to rule out methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), should be performed, especially since treatment will normally require potent topical glucocorticoid therapy for control. Treat bacteria and Candida infections orally because topical treatment can irritate and intensify pruritus. Proper hydration is essential for healing. Patients with lichen simplex chronicus that is intensely inflamed, excoriated, or eroded generally require medications in an ointment base, to avoid additional sensitizers and the drying effects of cream and lotion bases. A plain water soak in a tub for 5 minutes three times a day, followed by gentle patting of excess moisture and the application of a Class 3–1 corticosteroid ointment is the best approach for initial therapy, and must be done under cover of an appropriate oral antibiotic and fluconazole. Sedation is very helpful initially to stop scratching, with hydroxyzine or doxepin at night to tolerance. Systemic corticosteroids should be used for short periods of time for severe pruritus. Follow-up to prevent and manage relapse is essential.

(See Chapters 48 and 13)

Vulvar skin is thin, damp, and permeable. It is exposed to a wide range of insults from washcloths and vigorous scrubbing to caustic, irritating or allergenic cleansers, and topical products applied to alleviate symptoms. Irritant vulvar dermatitis is common, ranging from the diaper dermatitis seen in infants and elderly incontinent ladies to the chapped, sore vulva of the overzealous scrubbers. Allergic vulvar contact dermatitis is less common, with relevant allergens found in 30% of those tested.8

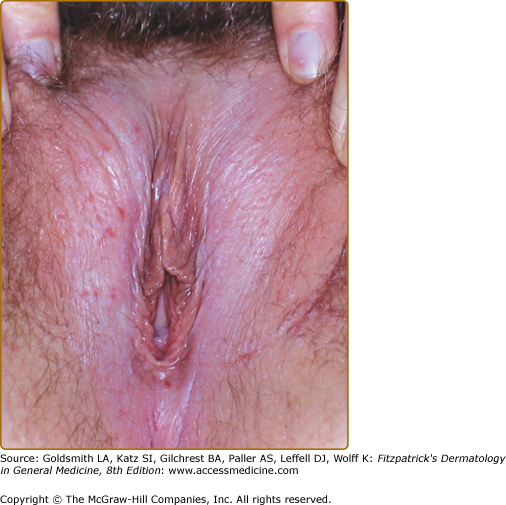

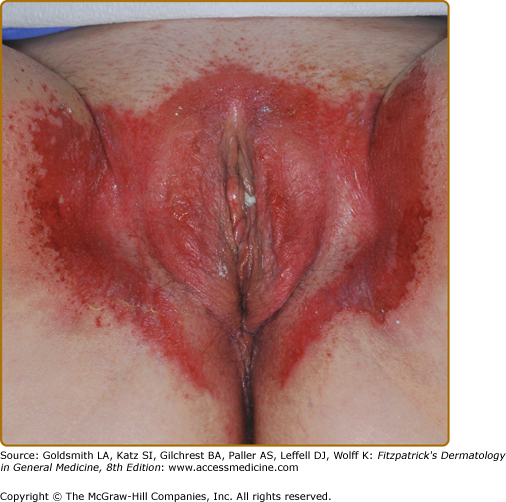

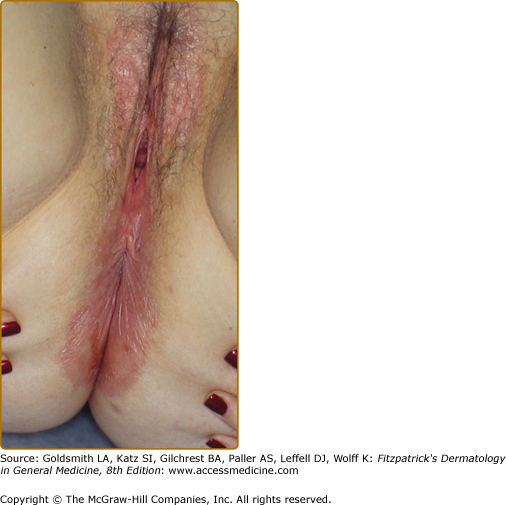

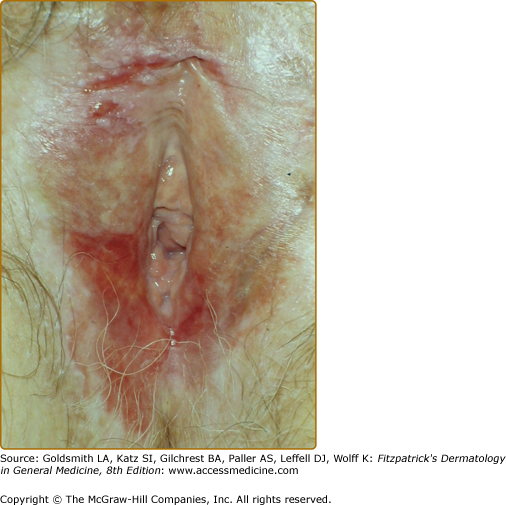

Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva can be either a primary or secondary diagnosis, acute or chronic. Either or both may commonly complicate any vulvar dermatosis. A patient with acute irritant contact dermatitis experiences burning on contact with the offending substance. Deep erythema is common. Vesiculation, rare, can occur on keratinized skin, whereas erosion is usual on modified mucous membranes (Fig. 78-3). Therapies such as fluorouracil, imiquimod, podophyllin resin, benzocaine, some topical antifungal creams, and topical gentian violet can produce a brisk reaction.9 Chronic irritant contact dermatitis is characterized by poorly demarcated erythema or hyperpigmentation that can be difficult to appreciate because the vulva normally is pink or dusky (eFig. 78-3.1). Lichenification and scale, when present, make diagnosis easier. Pruritus can be intense.

Although the British have found allergic contact dermatitis to be a common finding on the vulva, American physicians report few relevant positive results on patch tests for patients with eczematous vulvar skin.8–11

Nevertheless, women with refractory vulvar symptoms should be evaluated clinically and a thorough history taken to identify allergic contact dermatitis. In acute allergic contact dermatitis of the genital area, vesicles erode as quickly as they form, producing painful exudative erosions and plaques. Chronic allergic contact dermatitis is manifested more often by mild erythema and subtle edema. Notable scale is infrequent. Scratching in more severe and chronic cases induces lichenification. Common allergens include diphenhydramine, neomycin, polymyxin, sulfonamides, benzocaine, some antifungal creams, spermicides, glucocorticoids, some antiseptics, fragrances, and preservatives (see Chapter 13). As can occur with eyelid dermatitis, allergens can be carried inadvertently from fingertips to the vulva during the course of scratching or wiping. In addition, the habits of sexual partners can be important (consort dermatitis).

The therapy for vulvar contact dermatitis is the same as for this disease occurring in other areas and hinges most importantly on avoidance of irritants and allergens. Irritant, and to a lesser extent allergic, contact dermatitis can be a complicating factor in most vulvar conditions.12 It can also obscure underlying disease. Women with chronic symptoms often are well served by discontinuing all topical therapies (eFigs. 78-3.2 and 78-3.3). For a severe or extensive eruption, use systemic steroids, avoiding topicals except for a bland emollient like petrolatum. Be sure to stop all offending hygiene practices and control secondary infection and pruritus. For a mild-to-moderate eruption a Class II–IV topical steroid ointment applied twice daily can hasten improvement. Reevaluation 1 or 2 weeks later may reveal an underlying primary process.

(See Chapter 18)

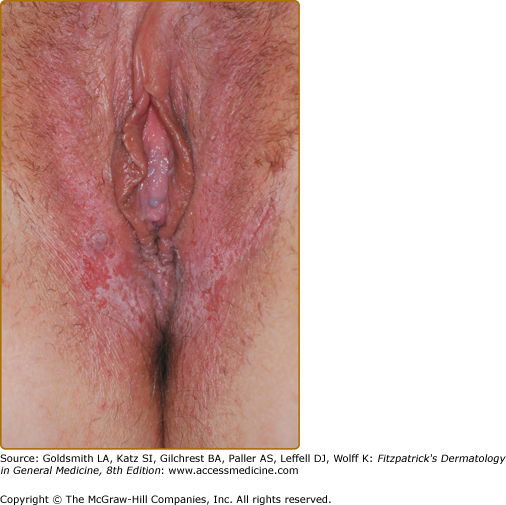

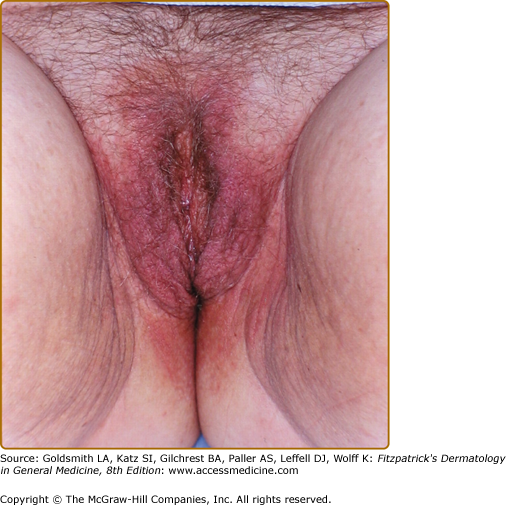

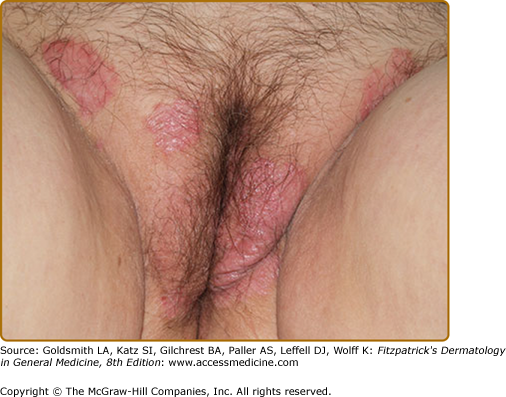

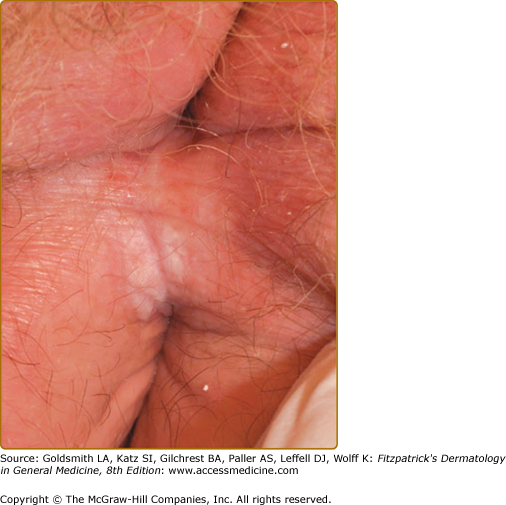

Vulvar psoriasis is too often missed. Women are embarrassed to mention it to their dermatologist. They show it to the gynecologist, unfamiliar with skin conditions, who cannot help with recognition and management. Dermatologists need to ask female psoriatics if they have genital rashes. Although vulvar psoriasis generally is accompanied by psoriasis in other typical locations, the vulva is a common site of Koebnerization. Vulvar psoriasis usually affects only fully keratinized skin, sparing the modified mucous membrane of the inner labia majora and the labia minora. Vulvar psoriasis typically exhibits dusky red, well-demarcated plaques. Rather than thick, silvery scale, the moistness of inverse psoriasis or a glazed, shiny surface texture is seen (Fig. 78-4, eFigs. 78-4.1, 78-4.2, and 78-4.3).

Genital psoriasis often responds well to topical therapy. A mid- or high-potency glucocorticoid ointment generally is required for significant clinical or symptomatic improvement. Calcipotriene ointment, tacrolimus ointment, or pimecrolimus cream can be tried as well, but some patients find these too irritating. For extensive psoriasis, methotrexate, oral retinoids, cyclosporine, or the newer biologics are required.

|

(See Chapter 65)

Lichen sclerosus is the commonest cause of chronic vulvar dermatosis. The prevalence is 1:300–1:1,000. The onset is bimodal in premenarchal girls and perimenopausal women.

Lichen sclerosus begins asymptomatically in most patients. Women often tolerate their disease comfortably until they develop a superimposed complicating event, such as candidiasis or atrophic vaginitis that produces itching, followed by scratching, and the process becomes self-perpetuating. At presentation, the most common symptom of lichen sclerosus is pruritus (mild or severe). Because vulvar skin affected by lichen sclerosus is fragile, scratching often produces painful erosions. Many women, by the time they come for treatment, exhibit late signs of lichen sclerosus, including remarkable textural changes and scarring with loss of normal vulvar architecture. Scarring and narrowing of the introitus may make intercourse painful, even intolerable.

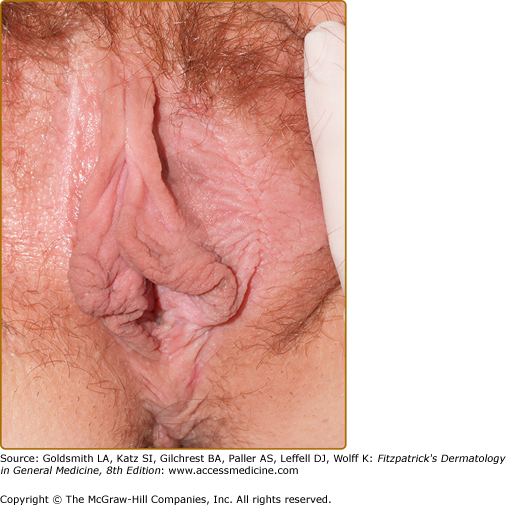

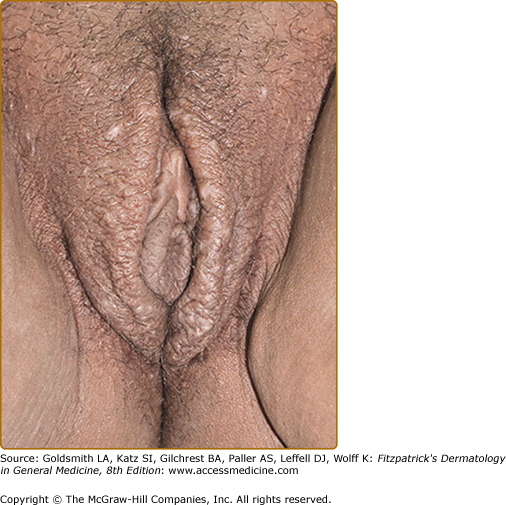

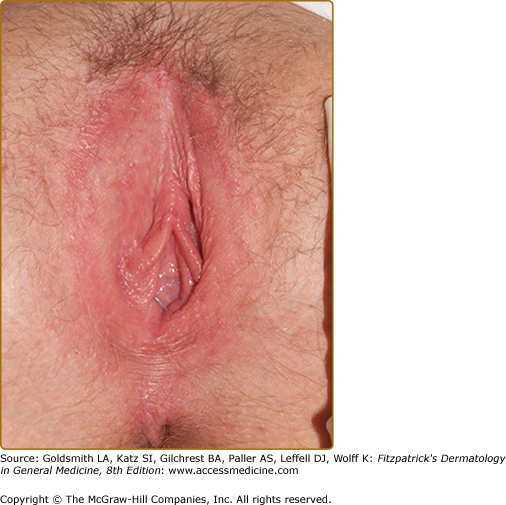

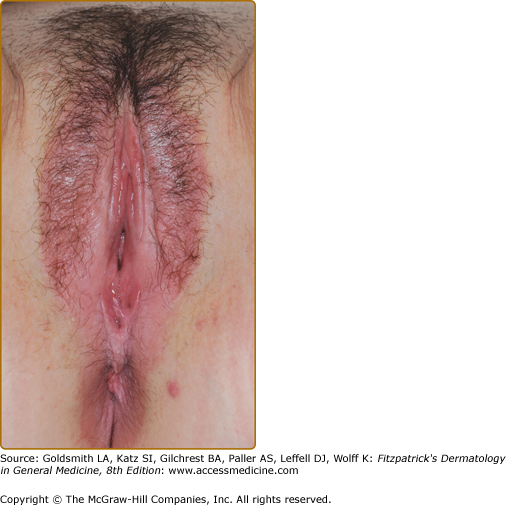

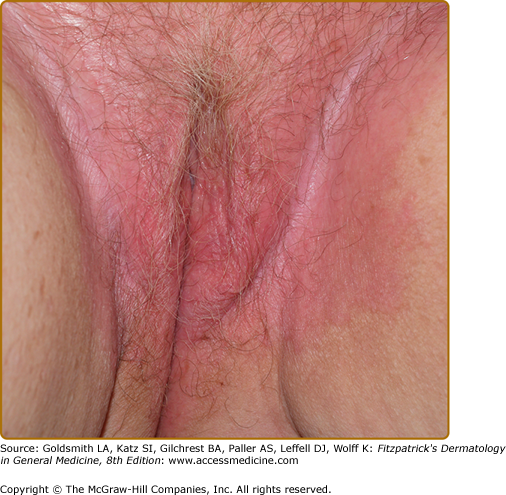

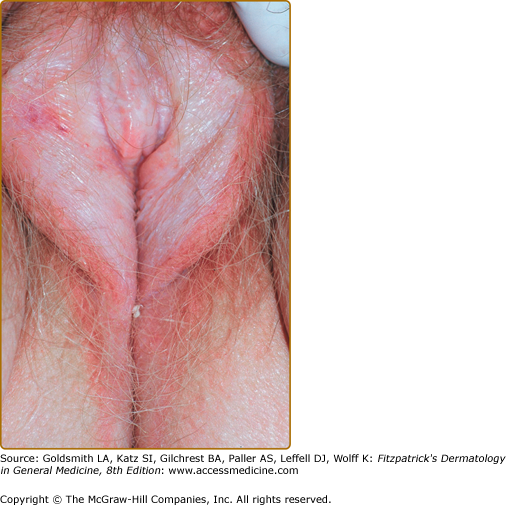

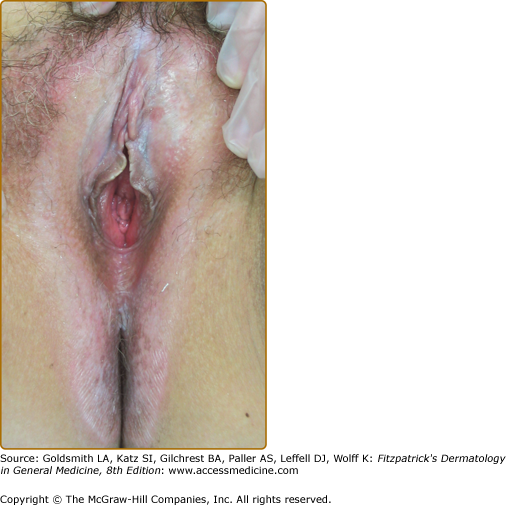

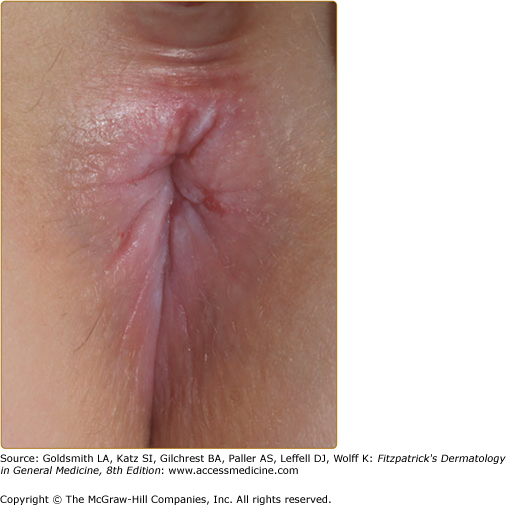

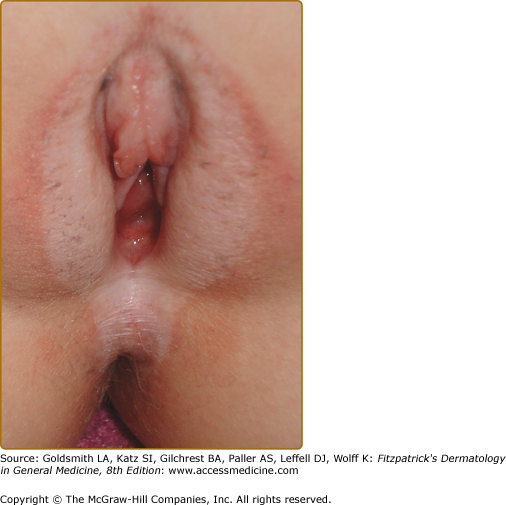

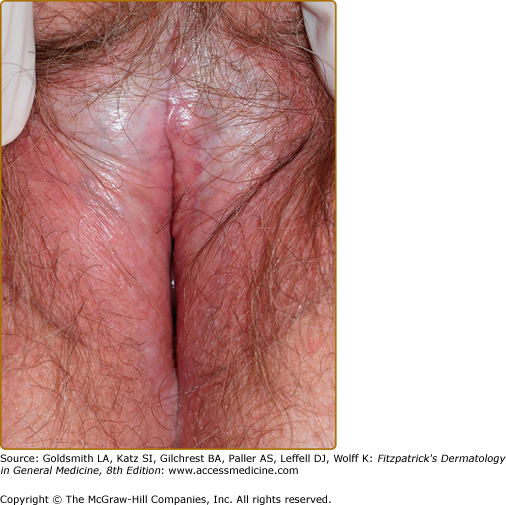

Lichen sclerosus begins with white papules or plaques that often occur first on the anterior vulva and periclitorally. Although these papules and plaques are sometimes smooth and somewhat waxy, especially when they occur on moist skin, the classic presentation is one of a hypopigmented, well-demarcated plaque with a shiny, crinkled cellophane-like surface (Fig. 78-5 and eFigs. 78-5.1, 78-5.2, 78-5.3, and 78-5.4). Generally, the skin is quite thin and fragile, with erosions and purpura being common manifestations. Some women, particularly those who experience intolerable itchiness, exhibit thickened hyperkeratotic skin with extensive secondary changes, including fissuring, crusting, and even bleeding (eFig. 78-5.5). Many patients with lichen sclerosus experience progressive scarring (eFig. 78-5.6). Resorption of the labia minora and scarring of the clitoral hood, which buries the clitoris, are common in long-standing disease (Fig. 78-6). Extragenital lichen sclerosus of keratinized skin occurs in a minority of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus and is most often located on the upper trunk and arms (see Chapter 65). Usually, extragenital lesions are asymptomatic.

eFigure 78-5.6

Chronic lichen sclerosus with flattening of most of the vulvar architecture and thickening and painful fissuring on the right periclitoral area and in the erosive area on the right lower vulvar trigone due to squamous cell carcinoma. Any questionable new changes on the vulva and lichen sclerosus need to be biopsied.

An association of lichen sclerosus with circulating autoantibodies has been reported, but the only association with autoimmune disease sufficient to justify laboratory testing is with hypothyroidism.13

Fully developed lichen sclerosus with hypopigmentation and distinctive shiny or crinkled textural changes is easily recognized. Unfortunately, lichen sclerosus is sometimes subtle or mimics other diseases (Box 78-3).

Sexual dysfunction results from scarring and introital narrowing. Four to five percent of patients are reported to develop squamous cell carcinoma in the natural course of lichen sclerosus.4,15 Squamous cell carcinomas occurred primarily in patients with chronic hyperkeratosis or erosions. With effective topical therapy, this risk is understood to be lower.

Although topical glucocorticoids reduce symptoms, they do not always normalize the skin texture or prevent scarring. The application of a superpotent topical preparation once or twice a day alleviates symptoms within a few days, but several months of therapy is required for resolution of the clinical findings.14,15

Most patients require 3–5 months of once- or twice-daily application to achieve maximal improvement. Patients should be followed monthly during periods of daily treatment to monitor the skin for steroid side effects and for improvement so that the frequency of application can be decreased.16 As an adjunct therapy for the first week or two to control scratching and hasten healing, sedating dosages of an antihistamine or a tricyclic antidepressant are helpful. Any infection must be controlled.

Lichen sclerosus usually is not eliminated permanently by therapy. One survey showed an 84% recurrence rate among patients off therapy.17 Despite the frequent requirement for long-term maintenance therapy, however, there is no proven optimal schedule. Most patients do well with two to three carefully localized weekly applications of a superpotent glucocorticoid on an ongoing basis.

No other treatments for lichen sclerosus produce the striking and prompt benefit of a topical superpotent glucocorticoid. Intralesional triamcinolone is used in resistant areas. In addition, other medical therapies generally have shown benefit only in open-label series. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus (see Chapter 221) have been reported effective.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree