Dermatomyositis: Introduction

|

The idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIDMs) are a heterogeneous group of genetically determined autoimmune disorders that predominately target the skeletal musculature and/or skin and typically result in symptomatic skeletal muscle weakness and/or cutaneous inflammatory disease. Some physicians continue to refer to this group of clinical disorders by an earlier designation, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Among the IIDM, dermatomyositis (DM) is of special interest to the dermatologist due the universal presence of a hallmark pattern of cutaneous inflammation. DM is the only idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) that expresses a characteristic pattern of primary cutaneous inflammation.

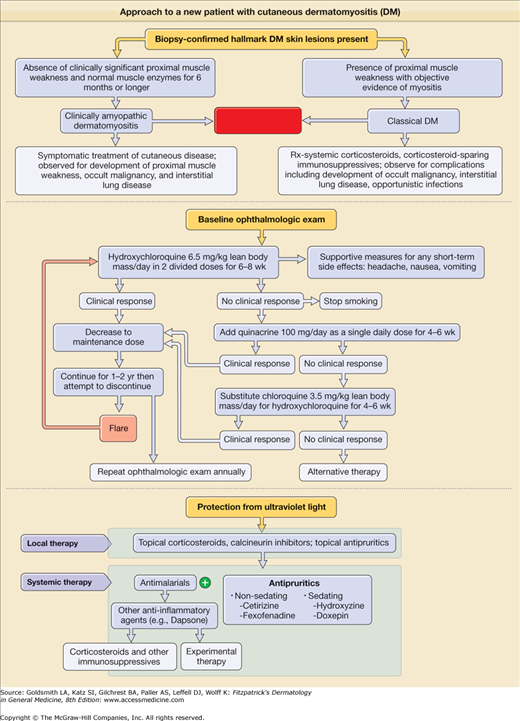

In this chapter, the term classic DM is used to refer to DM as traditionally defined (i.e., the concurrence of myositis resulting in clinically significant proximal muscle weakness and a set of hallmark inflammatory skin lesions occurring in a specific anatomical distribution). Also of interest to the dermatologist is the subgroup of patients who express the hallmark cutaneous manifestations of DM for prolonged periods (6 months or longer) without developing clinically evident muscle weakness. This pattern of DM expression is referred to as clinically amyopathic DM (CADM); this term is synonymous with the historical designation, dermatomyositis sine myositis.

On occasion, other organ systems, such as the lungs (interstitial lung disease), joints (arthritis), and heart (cardiomyopathy, conduction defects), are targeted by inflammatory injury in IIM patients. In addition, differences exist between classic DM presenting in adults and that presenting in children. For example, juvenile-onset classic DM is associated with higher rates of vasculopathy/vasculitis resulting in the complication of dystrophic calcification, whereas adult-onset classic DM is associated with a significantly increased risk of internal malignancy and interstitial lung disease.

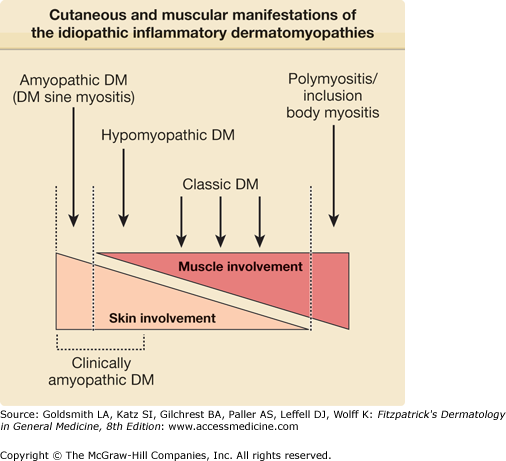

The diagnostic criteria for DM under the current consensus IIM classification system have not allowed for the inclusion of cutaneous-only or cutaneous-predominant subsets of DM, such as amyopathic DM and hypomyopathic DM, which together are referred to here as CADM (see eTable 156-0.1). A more inclusive disease category designation, “idiopathic inflammatory dermatomyositis,” has been proposed by one of the authors (Richard D. Sontheimer) as an alternative to the “IIM” designation because it allows for the inclusion of these cutaneous subsets of DM1–16 (eTable 156-0.2). Other rheumatologic disorders such as lupus erythematous (LE) and scleroderma are broadly recognized to include skin-only subsets (e.g., discoid LE, morphea). However, the group designation “idiopathic inflammatory dermatomyopathies” has yet to be broadly embraced.

Term | Definition |

|---|---|

Amyopathic DMb | Subset of DM characterized by biopsy-confirmed hallmark cutaneous manifestations of classical DM occurring for 6 months or longer with no clinical evidence of proximal muscle weakness and no serum muscle enzyme abnormalities. If more extensive muscle testing is carried out, the results should be within normal limits [if such results are positive or abnormal, the patient should be classified as having “hypomyopathic dermatomyositis” (see below)]. Exclusion criteria for amyopathic DM for the purpose of clinical studies include the following: 1. Treatment with systemic immunosuppressive therapy for 2 consecutive months or longer within the first 6 months after skin disease onset (such therapy could prevent the development of clinically significant myositis). 2. Use of drugs known to be capable of producing isolated DM-like skin changes (e.g., hydroxyurea, statin cholesterol-lowering agents) at the time of onset of the cutaneous DM changes. |

Classic DM | Presence of the hallmark cutaneous manifestations of DM, proximal muscle weakness, and objective evidence of muscle inflammation characteristic of DM. |

Clinically amyopathic DM (CADM) | An umbrella designation that refers both to amyopathic DM and to hypomyopathic DM. This designation emphasizes that the predominant clinical problem is skin disease in affected patients. |

DM sine myositis | Historic term synonymous with clinically amyopathic DM. |

DM-specific skin disease | Clinicopathologic pattern of skin changes appearing only in DM (analogous to the concept of “lupus erythematosus-specific skin disease” proposed by Gilliam in 1975).127 |

Hallmark cutaneous lesions/changes of DM | Skin lesions that alone or in combination are seen only in patients with some form of DM (synonymous with DM-specific skin disease). |

Hypomyopathic DM | DM-specific skin disease but no clinical evidence of muscle disease (i.e., no muscle weakness) but subclinical evidence of myositis on laboratory, electrophysiologic, and/or radiologic evaluation. |

Idiopathic inflammatory dermatomyositis (IIDMs) | More inclusive term used to designate is found the spectrum of illness that has conventionally been referred to as the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and dermatomyositis/polymyositis. |

Dermatomyositis (DM)

|

Polymyositis (PM)

|

Inclusion Body Myositis Other Clinical-Pathologic Subgroups of Myositis

|

Thus, IIDM represents a heterogeneous group of clinical disorders that can be conveniently conceptualized as a continuum of illness with subgroups of patients who share common clinical and immunologic features at distinct positions along this spectrum (Fig. 156-1).

Epidemiology

Cutaneous involvement occurs in 30% to 40% of adults and in 95% of children with IIDM. By definition, skin disease is absent in patients with PM and present in 100% of patients with classic DM and CADM. Skin disease activity can precede muscle disease activity in classic DM by weeks to several months.

Classic DM can occur from infancy to adulthood and most frequently presents in the fifth and sixth decades (PM is extremely rare in children). The incidence of classic IIDM between 1963 and 1982 was estimated to be 5.5 cases per million. The incidence probably is higher, inasmuch as this study17 was based only on hospital inpatient-ascertained diagnoses and did not include cases of CADM. Familial concordance occurs rarely, and concordant disease expression has been reported in identical twins.

The epidemiology of juvenile-onset classic DM in the United States has been reviewed.18 For children 2–17 years of age, the estimated annual incidence rates from 1995 to 1998 in the United States ranged from 2.5 to 4.1 cases per million children, and the 4-year average annual rate was 3.2 per million children. Estimated annual incidence rates by race were 3.4 for white non-Hispanics, 3.3 for African American non-Hispanics, and 2.7 for Hispanics. Girls were affected more than boys (ratio of 2.3:1). Cutaneous ulceration occurring as a result of infarctive vasculopathy and subsequent calcification is more common in the childhood form of the disease.

Environmental factors have been implicated as disease triggers. Seasonality has been noted in both juvenile-onset and adult-onset DM, which suggests the possibility of an infectious etiology. DM- and PM-like syndromes have been reported in patients infected with coxsackievirus, parvovirus B19, Epstein–Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1.

A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota identified 29 patients over a 30-year period with dermatomyositis of which 21% had the clinically amyopathic subtype. The incidence of CADM in the study was 2.08 per million persons.19–24 In Europe, a similar incidence has been observed,25 whereas in Asia, CADM appears to be relatively more common. A retrospective analysis of 28 patients with DM at the National Skin Center in Singapore between 1996 and 1998 revealed that 13 (46%) had CADM.26 In another cohort of 143 Taiwanese patients with IIDM treated in a veterans hospital system, CADM was the second most commonly encountered type of IIDM (14%) after classic adult-onset DM (64%). CADM was somewhat more common than juvenile-onset IIDM (13%) and PM (10%) in this study.27 In Asian patients, adult-onset CADM appears to be more common in males.27 One of the authors (Richard D. Sontheimer) has personally observed an unreported familial constellation of CADM in a father and his only children—two adult daughters. Indirect evidence suggests that CADM has human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations similar to those found in patients with classic DM (i.e., HLA-DQA1).28

Literature Review

![]() A systematic review of the published literature on adult-onset CADM has been presented.29 Two-hundred ninety-one reported cases of adult-onset CADM (18 years or older) in over 19 countries were analyzed. The average duration of DM skin disease was 3.74 years [range, 6 months (by definition) to 20 years], and 73% of cases were females. Among 37 patients with hypomyopathic DM who were identified, the average duration of disease was 5.4 years, and none had developed clinically significant weakness at the time the case reports were published. Thirty-seven of the reported CADM patients developed muscle weakness longer than 6 months after onset of their skin disease (15 months to 6 years). The data for such patients were subanalyzed under the designation “CADM evolving to classic DM.” Somewhat surprisingly, 36 of 291 (13%) of the identified reported patients with adult-onset CADM developed interstitial lung disease. In addition, this review also identified ten published cases of individuals who had hallmark DM skin lesions and interstitial lung disease without muscle weakness, 7 of whom died from interstitial lung disease less than 6 months after the onset of their DM skin disease. Because these patients did not satisfy the definition of CADM, the term premyopathic DM coined by others was used in this analysis to refer to such patients. An associated internal malignancy was found in 41 of 291 (14%) of the identified adult-onset CADM cases analyzed in this review. However, the authors point out that publication bias might exist concerning this point and raised the idea that the risk of internal malignancy in adult-onset CADM might be lower than that associated with classic DM. A positive result on antinuclear antibody (ANA) tests was obtained in 63% and myositis-specific autoantibodies (e.g., Jo-1, Mi-2) were found in only 3.5% of the reported CADM cases analyzed in this systematic review.

A systematic review of the published literature on adult-onset CADM has been presented.29 Two-hundred ninety-one reported cases of adult-onset CADM (18 years or older) in over 19 countries were analyzed. The average duration of DM skin disease was 3.74 years [range, 6 months (by definition) to 20 years], and 73% of cases were females. Among 37 patients with hypomyopathic DM who were identified, the average duration of disease was 5.4 years, and none had developed clinically significant weakness at the time the case reports were published. Thirty-seven of the reported CADM patients developed muscle weakness longer than 6 months after onset of their skin disease (15 months to 6 years). The data for such patients were subanalyzed under the designation “CADM evolving to classic DM.” Somewhat surprisingly, 36 of 291 (13%) of the identified reported patients with adult-onset CADM developed interstitial lung disease. In addition, this review also identified ten published cases of individuals who had hallmark DM skin lesions and interstitial lung disease without muscle weakness, 7 of whom died from interstitial lung disease less than 6 months after the onset of their DM skin disease. Because these patients did not satisfy the definition of CADM, the term premyopathic DM coined by others was used in this analysis to refer to such patients. An associated internal malignancy was found in 41 of 291 (14%) of the identified adult-onset CADM cases analyzed in this review. However, the authors point out that publication bias might exist concerning this point and raised the idea that the risk of internal malignancy in adult-onset CADM might be lower than that associated with classic DM. A positive result on antinuclear antibody (ANA) tests was obtained in 63% and myositis-specific autoantibodies (e.g., Jo-1, Mi-2) were found in only 3.5% of the reported CADM cases analyzed in this systematic review.

![]() Very little information currently exists about the incidence of juvenile-onset CADM. In a retrospective analysis of data for all children with DM seen at an academic medical center in Pennsylvania between 1968 and 1998, 2 of 16 (12%) were categorized as having CADM.30 A systematic review of the published literature on juvenile-onset CADM has recently been performed that included 69 cases of juvenile-onset CADM reported from 1963 to 2005.20 Of these, 38 (56%) could be subclassified as juvenile-onset amyopathic DM and 12 (18%) as juvenile-onset hypomyopathic DM. In 18 (26%) of the patients identified as having juvenile-onset CADM, the disorder was reported to have subsequently evolved into juvenile-onset classic DM. Overall, the mean age at diagnosis was 10.5 years (range, 2–17 years), with a nearly equal number of males and females affected. The mean follow-up time was 3.9 years. Among cases for which diagnostic testing was reported, 10 of 20 (50%) had positive results on ANA antibody titer, 2 of 10 (20%) had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 0 of 10 had positive results on tests for myositis-specific antibodies, and 2 of 52 (4%) had an elevated creatine kinase (CK) level. Aldolase level was reported for 11 patients and was concordant with the CK level in each case. Of patients who did not have an elevated CK level, 3 in 22 (14%) had abnormal electromyographic (EMG) results, 1 in 9 (11%) had abnormal muscle biopsy findings, and 1 in 9 (11%) had abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Three of 69 patients (4%) were reported to have calcinosis, 1 of 69 (1.4%) was reported to have interstitial lung disease, and no cases of severe vasculopathy or internal malignancy were reported. The patterns of results of laboratory and ancillary muscle testing of these patients were similar to those of patients with adult-onset CADM, whereas the clinical course and complication rate paralleled those of classic juvenile-onset DM, although the rate of complications was lower.

Very little information currently exists about the incidence of juvenile-onset CADM. In a retrospective analysis of data for all children with DM seen at an academic medical center in Pennsylvania between 1968 and 1998, 2 of 16 (12%) were categorized as having CADM.30 A systematic review of the published literature on juvenile-onset CADM has recently been performed that included 69 cases of juvenile-onset CADM reported from 1963 to 2005.20 Of these, 38 (56%) could be subclassified as juvenile-onset amyopathic DM and 12 (18%) as juvenile-onset hypomyopathic DM. In 18 (26%) of the patients identified as having juvenile-onset CADM, the disorder was reported to have subsequently evolved into juvenile-onset classic DM. Overall, the mean age at diagnosis was 10.5 years (range, 2–17 years), with a nearly equal number of males and females affected. The mean follow-up time was 3.9 years. Among cases for which diagnostic testing was reported, 10 of 20 (50%) had positive results on ANA antibody titer, 2 of 10 (20%) had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 0 of 10 had positive results on tests for myositis-specific antibodies, and 2 of 52 (4%) had an elevated creatine kinase (CK) level. Aldolase level was reported for 11 patients and was concordant with the CK level in each case. Of patients who did not have an elevated CK level, 3 in 22 (14%) had abnormal electromyographic (EMG) results, 1 in 9 (11%) had abnormal muscle biopsy findings, and 1 in 9 (11%) had abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Three of 69 patients (4%) were reported to have calcinosis, 1 of 69 (1.4%) was reported to have interstitial lung disease, and no cases of severe vasculopathy or internal malignancy were reported. The patterns of results of laboratory and ancillary muscle testing of these patients were similar to those of patients with adult-onset CADM, whereas the clinical course and complication rate paralleled those of classic juvenile-onset DM, although the rate of complications was lower.

An increasing number of cases of DM are reported to be caused or exacerbated by systemic medications. A number of different drug classes have been implicated including statin-type cholesterol-lowering agents.31,32 The average incubation time is approximately 2 months. The majority of these cases present with both myositis and pathognomonic cutaneous findings and resolve with discontinuation of the medication. Pulmonary involvement appears to be uncommon in drug-induced DM.33 Long-term hydroxyurea therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia can produce a DM-like cutaneous eruption that is clinically and histopathologically similar to that of idiopathic DM-specific skin disease.21 This subtype of drug-induced DM is unique in that muscle weakness and other systemic symptoms are absent. Painful leg ulcers are often seen in association, as are xerosis and cutaneous atrophy. This symptom complex usually occurs only after the patient has been treated with hydroxyurea for long periods (2–10 years). The presence of concurrent therapy with hydroxyurea has been proposed as the exclusion criterion for CADM.1

Etiology and Pathogenesis

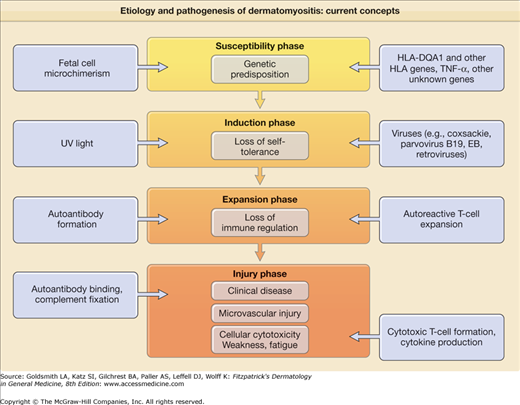

The inflammatory nature of the muscle and skin manifestations coupled with the characteristic humoral autoimmune abnormalities has led to the hypothesis that DM results from a genetically determined, aberrant autoimmune response to environmental agents. Figure 156-2 presents a summary overview of current thought in this area. Like other systemic autoimmune diseases involving autoantibody production such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), DM is thought to evolve through multiple sequential phases: the susceptibility phase, the induction phase, the expansion phase, and the injury phase.

The susceptibility phase of DM is thought to result largely from a genetic predisposition. DM is one of the human autoimmune diseases that is linked to the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (HLA-A1, C7, B8, C4AQ0, C4B1, DR3, DQ2).22 PM and DM have been specifically associated with HLA-B8, DR3, and DRw52, especially in white patients. This association is likely a result of linkage disequilibrium with HLA-DQA1*0501. The production of antisynthetase antibodies such as Jo-1 is strongly linked to HLA-DR3 and even more strongly linked to its supertypic specificity HLA-DRw52.

A single nucleotide polymorphism in the tumor necrosis factor-α promoter (TNF-α-308A), which is also a component of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype, has been associated with disease chronicity, calcinosis, and high levels of TNF-α in a cohort of white patients with juvenile-onset classic DM.23 This same TNF-α promoter polymorphism has been associated with photosensitive subacute cutaneous LE.34 This same TNF-α promoter polymorphism has been associated with photosensitive subacute cutaneous LE.24,35 Several gene polymorphisms associated with low production of mannose-binding protein, a molecule involved in the physiologic clearance of apoptotic cells, have been associated with adult DM.24 There has also been a single case report of adult-onset CADM that evolved to classic DM in a young Japanese woman who was shown to be genetically deficient in the fifth component of complement.36

The cutaneous manifestations of DM are precipitated or exacerbated by natural and artificial sources of ultraviolet (UV) light.37 Approximately 50% of patients with DM experience photosensitivity. The action spectrum appears to include both UVB and UVA light. UV radiation intensity has been shown to associate with the proportional incidence of DM compared to other IIMs and correlate with the detection of anti-Mi-2 antibodies in women.38 Environmental stimuli, including UV radiation and infection, could represent inductive factors in DM leading to loss of self-tolerance. Various types of infections have been circumstantially implicated as causative factors in DM. These include infection with RNA viruses such as coxsackievirus, echovirus, and human retroviruses (i.e., human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1 and human immunodeficiency virus). Nonviral pathogens such as Toxoplasma gondii have also been implicated. However, repeated attempts to confirm persistent myotropic infection by viruses or other pathogens have not been successful.

The expansion phase of DM is marked by autoantibody production signaling the loss of normal immune regulation. DM is associated with the production of a number of specific autoantibodies that probably predates by some period the first evidence of clinical disease activity (Table 156-1). Whether these autoantibodies are truly pathogenetic or represent only a by-product of muscle injury is unknown. It has been suggested that CADM might be associated with a specific autoantibody profile (antibodies to 140-kDa, 155-kDa, and Se antigens).39,40

Autoantibody | Median Prevalencea | Molecular Specificity | Clinical Association |

|---|---|---|---|

High Specificity for DM/PM | |||

155 kDa and/or Se | 20%–80% | transcriptional intermediary factor-1γ | Classic DM, clinically amyopathic DM with increased risk of internal malignancy |

140 kDa | 53% | helicase C domain protein 1 (IFIH1)/melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA-5) | Clinically amyopathic DM with increased risk for interstitial lung disease |

Jo-1 | 20% | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase | PM, antisynthetase syndrome |

Mi-2 | 15% | Helicase nuclear proteins | Shawl sign, cuticular overgrowth |

SRP | 5% | Signal-recognition particle | Fulminant DM/PM, cardiac involvement |

PL-7 | 3% | Threonyl-tRNA synthetase | Antisynthetase syndrome |

PL-12 | 3% | Alanyl-tRNA synthetase | Antisynthetase syndrome |

OJ | Rare | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase | Antisynthetase syndrome |

EJ | Rare | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase | Antisynthetase syndrome, possibly increased frequency of skin changes |

Fer | Rare | Elongation factor 1α | — |

Mas | Rare | Small RNA | — |

KJ | Rare | Translation factor | — |

Low Specificity for DM/PM | |||

ANA (most common nuclear immunofluorescence patterns—specked and nucleolar) | 40% | Clinically amyopathic DM (80%) | |

SsDNA | 40% | SLE, SSc | |

PM-Scl (PM-1) | 40% | Ribosomal RNA processing enzyme | Overlap with scleroderma |

Ro (52-kDa Ro) | 15% | RNP | Overlap with SSJ, SCLE, neonatal LE/CHB, SLE |

U1RNP | 10% | U1RNP | Overlap connective tissue disease |

Ku | 3% | DNA end-binding repair protein complex | Overlap with scleroderma |

U2RNP | 1% | U2RNP | Overlap with scleroderma |

It is thought that autoantibodies, immune complexes, and/or autoreactive T cells play a major role in the tissue injury phase of DM. Cell-mediated immune activity against muscle autoantigens is thought to be primarily responsible for the muscle injury that occurs in PM. Both myocytotoxic CD3+ T-cell clones and non-HLA-restricted myocytotoxic cells of other lineages have been identified in the peripheral blood of patients with inflammatory myopathies.41 Little has been done in the past experimentally to date to probe for T-cell-mediated cytotoxic epidermal or dermal cell injury in DM skin lesions.

Predominantly humoral autoimmune mechanisms targeting the microvasculature have been implicated in the pathogenesis of muscle injury in DM. Microvascular ischemia is an early feature of DM muscle involvement. Components of the C5 to C9 membrane attack complex are regularly found in the walls of microvessels in muscle biopsy specimens from DM patients.

There is not always good agreement between the degree of muscle weakness or fatigue experienced by patients with classic DM and the degree of inflammation noted in muscle biopsy specimens and the elevation of serum muscle enzyme levels. This observation has led to the idea that inflammatory cytokines might be capable of mediating metabolic disturbances within muscle that can exacerbate muscle weakness and fatigue.42 As with other rheumatic diseases such as systemic sclerosis, maternal microchimerism has been observed in children with juvenile classic DM.43 The pathogenetic significance of the presence of alloreactive maternal lymphoid cells in the circulation, muscle, and skin of patients with juvenile DM is unknown.

The pathogenesis of cutaneous inflammation in classic DM and CADM and has received little attention, owing in part to the lack of an experimental animal model of this pattern of cutaneous inflammation. Histopathologic analysis of cutaneous DM reveals three general abnormalities: (1) a cell-poor interface dermatitis, (2) a vasculopathy of dermal microvessels, and (3) prominent dermal mucin deposition. These histopathologic elements can be precipitated or exacerbated by exposure to UV radiation.

Detailed Immunopathology

![]() The immunopathology of cutaneous DM includes a variable degree of immunoglobulin and complement deposition (including components of the C5 to C9 membrane attack complex) at the dermal–epidermal junction and within the dermal microvasculature. The presence of C5 to C9 membrane attack complex been suggested to occur more commonly in the walls of dermal microvessels in cutaneous DM lesions than in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE) lesions.44

The immunopathology of cutaneous DM includes a variable degree of immunoglobulin and complement deposition (including components of the C5 to C9 membrane attack complex) at the dermal–epidermal junction and within the dermal microvasculature. The presence of C5 to C9 membrane attack complex been suggested to occur more commonly in the walls of dermal microvessels in cutaneous DM lesions than in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE) lesions.44

![]() The high-responder TNF-α-308A promoter polymorphism that has been linked to photosensitive subacute cutaneous LE has also been associated with juvenile-onset classic DM. Epidermal keratinocytes containing the TNF- α-308A promoter allele have been shown to produce exaggerated levels of TNF-α in the presence of interleukin-1α after exposure to UV B radiation. Exaggerated UVB light-induced TNF-α production could be related to the elevated levels of epidermal keratinocyte apoptosis that have been observed in both LE and DM skin lesions. These observations also raise the possibility that TNF-α-inhibiting therapy with agents such as recombinant monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab) or decoy receptor fusion proteins (etanercept) might be of value in selected patients with photosensitive DM as well as subacute cutaneous LE.

The high-responder TNF-α-308A promoter polymorphism that has been linked to photosensitive subacute cutaneous LE has also been associated with juvenile-onset classic DM. Epidermal keratinocytes containing the TNF- α-308A promoter allele have been shown to produce exaggerated levels of TNF-α in the presence of interleukin-1α after exposure to UV B radiation. Exaggerated UVB light-induced TNF-α production could be related to the elevated levels of epidermal keratinocyte apoptosis that have been observed in both LE and DM skin lesions. These observations also raise the possibility that TNF-α-inhibiting therapy with agents such as recombinant monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab) or decoy receptor fusion proteins (etanercept) might be of value in selected patients with photosensitive DM as well as subacute cutaneous LE.

![]() The predominant infiltrating cell types in hallmark inflammatory DM skin lesions are activated macrophages and CD4 memory phenotype T cells (45RO) that are focused around microvessels in the dermis.45 Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, a potent cellular source of interferon-α, have been shown to be present in substantial numbers in affected DM muscle46,47 and skin tissue.48 In addition, products of genes induced by interferon-α/β, including the myxovirus-resistance protein A (MxA) and the CXCL10 chemokine ligand (syn. IP10), are also highly overexpressed in DM muscle tissue45 and skin tissue.48 These observations have been used to support a hypothesis that T cells bearing the CXCR3 chemokine receptor are recruited into the skin of DM patients by CXCL10 after the local cutaneous generation of type I interferons (α/β) by activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The recruited CXCR3 receptor-bearing T cells then produce a T helper 1-biased immune cytotoxic effector reaction that results in features of cutaneous DM, including the characteristic interface dermatitis and microvascular endothelial cell injury.48

The predominant infiltrating cell types in hallmark inflammatory DM skin lesions are activated macrophages and CD4 memory phenotype T cells (45RO) that are focused around microvessels in the dermis.45 Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, a potent cellular source of interferon-α, have been shown to be present in substantial numbers in affected DM muscle46,47 and skin tissue.48 In addition, products of genes induced by interferon-α/β, including the myxovirus-resistance protein A (MxA) and the CXCL10 chemokine ligand (syn. IP10), are also highly overexpressed in DM muscle tissue45 and skin tissue.48 These observations have been used to support a hypothesis that T cells bearing the CXCR3 chemokine receptor are recruited into the skin of DM patients by CXCL10 after the local cutaneous generation of type I interferons (α/β) by activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The recruited CXCR3 receptor-bearing T cells then produce a T helper 1-biased immune cytotoxic effector reaction that results in features of cutaneous DM, including the characteristic interface dermatitis and microvascular endothelial cell injury.48

![]() The dermal microvasculature is more prominently altered in cutaneous DM than in cutaneous LE. It has been suggested that humoral factors can produce microvascular injury by triggering local activation of complement with deposition of C5 to C9, perhaps through endothelial-specific autoantibodies. Class II histocompatibility antigen expression by dermal endothelial cells is decreased in DM skin lesions, and this cell type appears to display an activation phenotype with respect to expression of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin). The net effect of microvascular injury in cutaneous DM is dropout of microvessels, which results in microvascular ischemia.

The dermal microvasculature is more prominently altered in cutaneous DM than in cutaneous LE. It has been suggested that humoral factors can produce microvascular injury by triggering local activation of complement with deposition of C5 to C9, perhaps through endothelial-specific autoantibodies. Class II histocompatibility antigen expression by dermal endothelial cells is decreased in DM skin lesions, and this cell type appears to display an activation phenotype with respect to expression of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and E-selectin). The net effect of microvascular injury in cutaneous DM is dropout of microvessels, which results in microvascular ischemia.

![]() Dermal mucin is a prominent finding in biopsy specimens from DM skin lesions. It has been suggested that this might be caused by the increased production of glycosaminoglycans by dermal fibroblasts as a result of immunologic stimulation. Evidence exists suggesting that mononuclear cells from patients with DM can be cytotoxic for cultured dermal fibroblasts. Serum factors in patients with LE can stimulate the production of glycosaminoglycans by dermal fibroblasts. Factor XIIIa+ dermal perivascular dendritic cells may be the source of abnormal mucin production in conditions such as reticular erythematosus mucinosis syndrome49 and possibly other autoimmune mucin-associated cutaneous disorders such as cutaneous DM.

Dermal mucin is a prominent finding in biopsy specimens from DM skin lesions. It has been suggested that this might be caused by the increased production of glycosaminoglycans by dermal fibroblasts as a result of immunologic stimulation. Evidence exists suggesting that mononuclear cells from patients with DM can be cytotoxic for cultured dermal fibroblasts. Serum factors in patients with LE can stimulate the production of glycosaminoglycans by dermal fibroblasts. Factor XIIIa+ dermal perivascular dendritic cells may be the source of abnormal mucin production in conditions such as reticular erythematosus mucinosis syndrome49 and possibly other autoimmune mucin-associated cutaneous disorders such as cutaneous DM.

![]() The preliminary observation that patients with CADM might preferentially produce a series of new autoantibodies (140 kDa, 155 kDa, Se)39,40 of apparent high disease specificity for CADM could yield a new experimental approach to addressing the pathogenesis of cutaneous DM. It is not yet known whether the autoantigens against which these autoantibodies are directed might be aberrantly expressed in the skin of patients with CADM endogenously or as a result of environmental stimuli (e.g., UV light), thereby targeting cutaneous tissue for autoantibody-mediated inflammatory injury.

The preliminary observation that patients with CADM might preferentially produce a series of new autoantibodies (140 kDa, 155 kDa, Se)39,40 of apparent high disease specificity for CADM could yield a new experimental approach to addressing the pathogenesis of cutaneous DM. It is not yet known whether the autoantigens against which these autoantibodies are directed might be aberrantly expressed in the skin of patients with CADM endogenously or as a result of environmental stimuli (e.g., UV light), thereby targeting cutaneous tissue for autoantibody-mediated inflammatory injury.

Clinical Findings

In 60% of patients with classic DM, the cutaneous lesions and muscle weakness present simultaneously. In 30% of patients, the cutaneous findings appear before the onset of muscle weakness. In 10%, muscle weakness precedes the appearance of skin lesions. The onset of cutaneous disease is typically accompanied by pruritus and/or a burning skin sensation. Sensitivity to sunlight or artificial sources of UV light is often present. Muscle weakness initially affects the shoulder and hip girdle musculature, presenting clinically as difficulty raising the arms above the head and arising from a sitting position. Weakness can be accompanied by muscle pain and tenderness.

eTable 156-1.1 presents the hallmark cutaneous manifestations of DM (to date, no recognizable differences in the clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic manifestations of classic DM and CADM have been reported). Some of these lesions, such as Gottron sign of DM (Fig. 156-3) and Gottron papules (see Fig. 156-4; Fig. 156-5), are pathognomonic of this disease, whereas others, such as periorbital, confluent, macular, violaceous (heliotrope) erythema/edema and grossly visible periungual telangiectasia associated with dystrophic cuticles, are highly characteristic.

Pathognomonic |

|

Characteristic |

|

Compatible with dermatomyositis |

|

Figure 156-3

Hand of a 30-year-old woman with a 15-year history of amyopathic dermatomyositis (DM). Note the confluent macular violaceous erythema, most pronounced over the metacarpophalangeal/interphalangeal joints, extending in a linear array overlying the extensor tendons of the hand and fingers. These changes, referred to as Gottron sign, are a hallmark cutaneous feature of DM. Early Gottron papules, an extension of Gottron sign, can be seen over the distal interphalangeal joints along with periungual erythema and dystrophic cuticles. In DM, the violaceous erythema is centered over the metacarpophalangeal/interphalangeal joints, whereas in lupus erythematosus these areas are relatively spared.

Figure 156-4

Fingers of an elderly woman with classic dermatomyositis (DM). Note the fully formed Gottron papules over the distal interphalangeal joints, a hallmark cutaneous feature of DM. Prominent grossly visible nail-fold telangiectasias are also present, along with dystrophic cuticles. The combination of Gottron papules and nail fold changes such as these is pathognomonic for DM. Such changes are seen to an equal degree in classic DM and amyopathic DM.

Figure 156-5

The confluent, macular, violaceous erythema of the V area of the upper chest and neck (V sign), when persistent over time, can evolve into poikilodermatous skin changes. Less evident in this photograph are periorbital edema and confluent, macular, violaceous (heliotrope) erythema of the upper eyelids. Note the absence of involvement of the malar areas, which are often involved in lupus erythematosus.

The primary skin change of DM is a highly characteristic, often pruritic, symmetric, confluent, macular violaceous erythema variably affecting the skin overlying the extensor aspect of the fingers, hands, and forearms; the arms, deltoid areas, posterior shoulders, and neck (the shawl sign); the V area of the anterior neck and upper chest; and the central aspect of the face, periorbital areas, forehead, and scalp (Fig. 156-6). Central facial involvement can occasionally simulate the appearance of seborrheic dermatitis with nasolabial fold involvement. The lateral aspects of the hips and thighs (holster sign) are also frequently involved.50 Lesions such as poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare (poikilodermatomyositis) and calcinosis cutis are often present in patients with DM but may also appear in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare) and scleroderma (SCL; calcinosis cutis). In addition, overlapping features of cutaneous DM and cutaneous SCL (see Chapter 155) can occur in the same individual (sclerodermatomyositis).

Several other types of skin lesions have been suggested to be characteristic of IIDM; however, there is not yet enough published experience to determine their true disease specificity or prevalence. The mechanic’s hand lesion consists of a nonpruritic, hyperkeratotic eruption accompanied by scaling, fissuring, and hyperpigmentation, which give the false appearance of the callused hands of a laborer. These changes are bilaterally symmetric and distributed along the medial aspect of the thumb and lateral aspect of the index and middle fingers. These hyperkeratotic changes can extend onto the palmar surface. A strong association between this skin lesion and the presence of active myositis and antisynthetase antibodies such as Jo-1 was originally suggested. However, subsequent observations indicate that this same skin change occurs in classic DM without all the elements of the antisynthetase syndrome, as well as in CADM.51–53

Table 156-2 presents the characteristic anatomic distribution of the hallmark cutaneous manifestations of DM. There is very little published information on the prevalence of involvement in these different anatomic locations. In some series reported by dermatologists, Gottron papules have been more commonly seen than periorbital heliotrope erythema, which by many outside of dermatology is felt to be the hallmark cutaneous manifestation of DM.

Anatomic Location | Lesions |

|---|---|

Scalp | CMVE; nonscarring diffuse alopecia |

Face | |

Periorbital region | CMVE (usually most intense on the upper eyelids), edema |

Malar eminences | CMVE sparing or involving the nasolabial fold114 |

Forehead, chin | CMVE |

Neck and shoulders | |

Anterior | CMVE evolving to poikiloderma |

Posterior | CMVE (shawl sign) |

Upper extremities | |

Arms, forearms | CMVE on the extensor aspects |

Elbows | CMVE usually most intense in this location (Gottron sign of dermatomyositis) |

Hands, fingers | |

Dorsal aspect | CMVE usually most intense over the extensor tendons and metacarpophalangeal/interphalangeal joints (Gottron sign), Gottron papules overlying the dorsal–lateral aspect of the metacarpophalangeal/interphalangeal joints, relative sparing of the dorsal aspects of the phalanges, periungual nail fold telangiectasia (often grossly visible), cuticular microvascular hemorrhage, dystrophic/ragged cuticles |

Palmar aspect | Mechanic’s hand lesion, mucinous plaques centered over the flexural creases |

Trunk | CMVE evolving to large unilateral areas of poikiloderma (poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare) commonly seen over the flanks and lower back |

Lower extremities | |

Thighs | CMVE (holster sign) |

Knees | CMVE (Gottron sign) |

Lower legs, feet | CMVE, often focal, centered over the medial malleoli; Gottron sign overlying the medial malleoli |

The violaceous hue of the cutaneous inflammation in lightly pigmented individuals is a striking clinical finding that usually is evident from the outset of disease activity. This hue helps to distinguish cutaneous DM from cutaneous LE, in which it is a late finding when present. It has been suggested that edema associated with the DM skin disease indirectly produces the violaceous hue by displacing the hyperemic cutaneous vasculature more deeply into the dermis. One might also speculate that this could result from the deoxygenation of blood flowing through an abnormal dermal microvascular bed. In this regard, it is interesting to note that cutaneous DM often presents in the skin over joints that is frequently stretched and thus often made to become transiently ischemic under normal physiologic conditions.

A striking clinical feature that helps to distinguish cutaneous DM from cutaneous LE is pruritus, which can be so severe in DM as to be disabling, even in the absence of systemic involvement. In addition to pruritus, DM patients often described severe burning, painful sensations associated with the DM skin inflammation. Some work has suggested that severe DM skin disease can have a greater impact on quality of life than other skin diseases such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis for which aggressive systemic immunomodulatory therapies are often used.54

A number of other skin changes can be encountered in patients with DM. Hyperkeratosis may follow the onset of the confluent, macular, violaceous erythema; however, the scale in DM skin lesions is usually less prominent than that in subacute cutaneous LE and discoid LE. Secondary skin changes in DM skin lesions include excoriation with secondary infection and ulceration. Subepidermal vesicles and/or bullae occasionally occur in areas of particularly intense cutaneous inflammation. Postinflammatory pigmentary changes, both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, occur. Older lesions may have white lacy markings somewhat similar to those of Wickham’s striae in lichen planus. Another similarity between cutaneous DM and lichen planus is the characteristic violaceous hue. Mucinous infiltration, a common histologic finding in the dermis of DM skin lesions, can be clinically prominent, producing an infiltrated, glistening appearance. Superficial erosions and ulcers can subsequently develop over the face and eyelids as well as in other areas affected by intense and protracted inflammation. Deep, irregular, retiform ulcers can also develop in areas of poikiloderma in both adults and children. It has been suggested that the penetrating ulcers reflecting vasculopathy can be a bad prognostic sign in both juvenile-onset and adult-onset DM.

Clinical experience suggests that, as with cutaneous LE/SLE, the activity of IIDM can be precipitated or exacerbated by emotional and physical stress, although there is scant published evidence. Strenuous physical exertion can be detrimental to patients who have active myositis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may identify edema/inflammation in skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia resulting from vasculopathy and vasculitis in patients with classic juvenile DM.55 In approximately 80% of the 26 children studied, MRI abnormalities indicating skin, subcutaneous, and/or fascial edema were observed. Clinical skin disease activity scores correlated positively with MRI skin edema scores. Five children developed soft tissue calcification in areas previously found to be edematous by MRI after 4–9-month follow-up intervals. These observations suggest that the assessment of soft tissue by MRI could be of value in predicting risk for developing calcification and in monitoring treatment to prevent or minimize it.

DM can develop as a component of an overlap connective tissue disorder. Most common are overlaps with SLE (see Chapter 155) and systemic sclerosis (see Chapter 157). Raynaud phenomenon, sclerodactyly, sclerosis of the skin, and the characteristic hyperpigmentation can all be present in the latter setting. The term sclerodermatomyositis describes the disorder in patients who present with DM and who develop striking features of SCL 6 months to 3 years later. In addition, myositis occurs in approximately 5% of patients who test positive for anti-Ro/SSA autoantibody (most of whom have Sjögren’s syndrome (see Chapter 161). The cutaneous manifestations of DM are not usually found in this setting.

The highly pruritic/burning scaling scalp involvement in patients with adult-onset classic DM and CADM that can be associated with nonscarring alopecia56 has also been found to occur in approximately 25% of patients with juvenile-onset DM.30 Localized scalp involvement can at times be the presenting manifestation of DM.

![]() A number of less common cutaneous lesions have been reported in patients with DM, including steroid-induced acanthosis nigricans, acquired ichthyosis, anasarca, facial edema without erythema, erythroderma, follicular hyperkeratosis, hypertrichosis, acquired ichthyosis, lichen planus, linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, livedo reticularis, malakoplakia, malignant atrophic papulosis, malignant erythema/suffusion, mucinosis, mucous membrane lesions, nasal septal perforation, panniculitis, glucocorticoid-induced acanthosis nigricans, urticaria/urticarial vasculitis, small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis, vulvar and scrotal involvement, and zebra-like stripes (centripetal flagellate erythema).5 Attention has been refocused on another unusual cutaneous finding in DM: pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP)-like lesions (i.e., type Wong DM).57 This variant usually presents as perifollicular keratosis over the extensor aspects of the upper extremities in adult-onset classic DM.58 It can simulate the appearance of florid keratosis pilaris, and some such patients have had atopic dermatitis as well as DM. However, more widespread patterns of involvement that better simulate PRP have been described, although such patients have not had other classic features of PRP such as desquamative palmar–plantar hyperkeratosis. Acquired lipodystrophy has been increasingly recognized in patients with juvenile-onset classic DM. One report of 20 patients indicated that 25% had evidence of lipodystrophy, whereas 50% demonstrated hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance.59 In another preliminary report, lipodystrophy was associated with calcinosis.60 Gingival telangiectasia is an oral mucosal manifestation of juvenile-onset classic DM.61 These mucosal changes are not specific for DM, however, and also occur in patients with LE and systemic sclerosis. Mucinous plaques centered over the flexural creases of the palms and fingers have also been seen in the context of IIDM.5,62

A number of less common cutaneous lesions have been reported in patients with DM, including steroid-induced acanthosis nigricans, acquired ichthyosis, anasarca, facial edema without erythema, erythroderma, follicular hyperkeratosis, hypertrichosis, acquired ichthyosis, lichen planus, linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis, livedo reticularis, malakoplakia, malignant atrophic papulosis, malignant erythema/suffusion, mucinosis, mucous membrane lesions, nasal septal perforation, panniculitis, glucocorticoid-induced acanthosis nigricans, urticaria/urticarial vasculitis, small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis, vulvar and scrotal involvement, and zebra-like stripes (centripetal flagellate erythema).5 Attention has been refocused on another unusual cutaneous finding in DM: pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP)-like lesions (i.e., type Wong DM).57 This variant usually presents as perifollicular keratosis over the extensor aspects of the upper extremities in adult-onset classic DM.58 It can simulate the appearance of florid keratosis pilaris, and some such patients have had atopic dermatitis as well as DM. However, more widespread patterns of involvement that better simulate PRP have been described, although such patients have not had other classic features of PRP such as desquamative palmar–plantar hyperkeratosis. Acquired lipodystrophy has been increasingly recognized in patients with juvenile-onset classic DM. One report of 20 patients indicated that 25% had evidence of lipodystrophy, whereas 50% demonstrated hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance.59 In another preliminary report, lipodystrophy was associated with calcinosis.60 Gingival telangiectasia is an oral mucosal manifestation of juvenile-onset classic DM.61 These mucosal changes are not specific for DM, however, and also occur in patients with LE and systemic sclerosis. Mucinous plaques centered over the flexural creases of the palms and fingers have also been seen in the context of IIDM.5,62

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree