Deep Fungal Infections: Introduction

Deep fungal infections comprise two distinct groups of conditions, the subcutaneous and systemic mycoses. Neither are common, and the subcutaneous mycoses, with some exceptions, are largely confined to the tropics and subtropics. In recent years, the systemic mycoses have become important opportunistic infectious complications in immunocompromised patients, including those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and patients receiving treatment for malignancies. They also include a group of primary respiratory infections, such as histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis, which may affect otherwise healthy individuals and those with underlying illness. The fungi that cause these respiratory infections are usually dimorphic or exist in a different morphologic phase (e.g., yeast or mold) at different stages of their life cycle.

Patients with subcutaneous fungal infections often present to a physician with signs of skin involvement. By contrast, patients with systemic mycoses only occasionally have skin lesions, either following direct involvement of the skin as a portal of entry or after dissemination from a deep focus of infection. There are a number of excellent texts about fungi and the diseases they cause.1–4

Subcutaneous Mycoses

|

The subcutaneous mycoses, or mycoses of implantation, are infections caused by fungi that have been introduced directly into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue through a penetrating injury, such as a thorn prick. Although many are tropical infections, others, such as sporotrichosis, are also prevalent in temperate climates; any of these infections may present as an imported disease in a patient who has originated from an endemic area, sometimes after a lapse of many years. The most common subcutaneous mycoses are sporotrichosis, mycetoma, and chromoblastomycosis. Rarer infections include lobomycosis and subcutaneous zygomycosis.

Sporotrichosis is a subcutaneous or systemic fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Sporothrix schenckii.5,6 The fungus occurs in the natural environment, presumably in mold (cells growing in a chain) form, but develops as a yeast (cells growing as single cells) in infections. The most frequent site of this infection is the dermis or subcutis. There is also a systemic form of sporotrichosis whose clinical features range from pulmonary infection to arthritis or meningitis. One important characteristic of the diagnosis of cutaneous lesions is the scarcity of organisms in tissue, making confirmation of the diagnosis by microscopy potentially difficult.6 Sometimes in tissue, fungal cells are surrounded by an eosinophilic refractile fringe, the asteroid body, that is a characteristic of the organism, although a similar phenomenon may occur with other infectious organisms (e.g., Schistosome eggs).

Infections occur in both temperate and tropical countries. They are seen in North, South, and Central America, including the Southern United States and Mexico, as well as in Africa, Egypt, Japan, and Australia.6 The countries where the highest rates of infection occur are Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa. However, sometimes hyperendemic areas are found where large numbers of cases occur.7 In the United States, infections are most common in the Midwestern river valleys. Infections are now rare in much of Europe. In nature, the fungus grows on decaying vegetable matter such as plant debris, leaves, and wood. Although it is usually a cause of sporadic infection, S. schenckii also may affect groups of workers exposed to the organism, such as those using straw as a packing material, gardeners, forestry workers, and those whose recreational activities bring them into contact with plant debris. A recent outbreak of sporotrichosis in Brazil has accentuated the role of exposure to other courses of infection, in this case domestic or feral cats. The organism is thought to be introduced into the skin through a local injury.

The two clinical varieties of sporotrichosis are the subcutaneous and systemic forms of disease.5,8,9 Subcutaneous sporotrichosis is by far the more common and includes two main forms: (1) lymphangitic and (2) fixed infections. The lymphangitic form is the more common and usually develops on exposed skin sites such as hands or feet. The first sign of infection is the appearance of a dermal nodule that breaks down into a small ulcer. Draining lymphatics become inflamed and swollen, and a chain of soft secondary nodules develops along the course of the lymphatic (Fig. 190-1); these also may break down and ulcerate. In the fixed variety, which accounts for about 15% of cases, the infection remains localized to one site, such as the face, and a granuloma develops that subsequently may ulcerate. Satellite nodules or ulcers may form around the rim of the primary lesion. Other clinical variants of subcutaneous sporotrichosis may mimic mycetoma, lupus vulgaris, and chronic venous ulceration. In some cases, deep extension of the infection may affect joints or tendon sheaths. Patients with AIDS who develop sporotrichosis often have multiple cutaneous lesions9 without prominent lymphatic involvement, but deep infections, such as arthritis, are also reported.

In the much rarer systemic form of sporotrichosis, lesions can develop almost anywhere, although chronic lung nodules, with cavitation, arthritis, and meningitis have been described most frequently. These may coexist with cutaneous lesions of sporotrichosis.

Conditions commonly confused with sporotrichosis are mycobacterial (see Chapter 184) and primary cutaneous Nocardia infections (see Chapter 185) and leishmaniasis (see Chapter 206). The nontuberculous mycobacterial infection due to Mycobacterium marinum (fish-tank granuloma), in particular, closely resembles lymphangitic sporotrichosis.

The best sources of diagnostic material are smears, exudates, and biopsies. S. schenckii is seen very rarely in direct microscopic examination because yeasts are usually present only in small numbers; the organism can be isolated readily on Sabouraud’s agar. In primary culture, the fungus grows as a mold, with compact, white colonies that darken with age. Microscopically, the hyphae produce small oval or triangular conidia either on specialized hyphae or elsewhere on the mycelium. Ideally, the organism should be converted to yeast phase on enriched media such as brain-heart infusion agar at 37°C (98.6°F) to complete the identification.

Pathologically, sporotrichosis causes a mixed granulomatous reaction with neutrophil microabscesses. The fungus, if present, is usually in the form of small (3–5 μm) cigar-shaped or oval yeasts that may, on occasion, be surrounded by a thick, radiating eosinophilic fringe forming the distinctive asteroid body. Organisms are usually sparsely distributed in lesions, and it may be necessary to scan several sections to identify a single yeast. An intradermal sporotrichin skin test is available in some countries and may have a role to play in allowing the physician to identify the most appropriate laboratory investigations to instigate.

Although spontaneous remissions may occur, most patients are treated with antifungal chemotherapy.10 Treatments include itraconazole, 200 mg daily, and terbinafine, 250 mg daily, which are better tolerated, and intravenous amphotericin B for deep infection; at present there has been little experience with voriconazole or posaconazole. In all cases, treatment is continued for at least 1 week after clinical resolution. A cheaper alternative is potassium iodide (saturated solution), 4–6 mL tid, which is effective in the cutaneous types of sporotrichosis and should be continued for 3–4 weeks after clinical cure. The daily dose is built up slowly from 1 mL tid over 2–3 weeks to avoid side effects such as hypersalivation and nausea. This is an inexpensive form of therapy, but it is unpalatable.

Mycetoma is a chronic localized infection caused by different species of fungi or actinomycetes. It is characterized by the formation of aggregates of the causative organisms, known as grains that are found within abscesses. These either drain via sinuses onto the skin surface or involve adjacent bone, causing a form of osteomyelitis. Grains are discharged onto the skin surface via these sinuses. The disease advances by direct spread, and distant metastatic sites of infection are very rare. Mycetomas caused by species of fungi are known as eumycetomas, and those caused by aerobic actinomycetes or filamentous bacteria are known as actinomycetomas (see Chapter 185). The organisms are usually soil or plant saprophytes11 that are only incidental human pathogens.

Mycetomas are mainly, but not exclusively, found in the dry tropics where there is low annual rainfall.11,12 They are sporadic infections that are seldom common, even in endemic areas.13 Occasionally, nonimported cases are reported from temperate climates, although in these cases, the most common organism is Scedosporium apiospermum. Actinomycetomas due to Nocardia sp. are most common in Central America and Mexico. In other parts of the world, the most common organism is a fungus, Madurella mycetomatis. The actinomycete Streptomyces somaliensis is isolated most often from patients originating from Sudan and the Middle East. The causative organisms of mycetoma have been isolated or detected by molecular methods from either soil or plant material, including Acacia thorns, in endemic areas.

The organisms are implanted subcutaneously, usually after a penetrating injury. It is unusual to find any underlying predisposition in patients with mycetoma, and the persistence of the organism after the initial inoculation appears to be related to its ability to evade host defenses through a variety of adaptations such as cell wall thickening and melanin deposition.14

The clinical features of both fungal and actinomycete mycetomas are very similar.12 They are most common on the foot, lower leg, or hand, although head or back involvement also may occur. Infection of the chest wall is most characteristic of Nocardia infections (see Chapter 185). The earliest stage of infection is a firm, painless nodule that spreads slowly with the development of papules and draining sinus tracts over the surface (Fig. 190-2). Local tissue swelling, chronic sinus formation, and later bone involvement distort and deform the original site of infection (Figs. 190-3 and 190-4). Lesions are seldom painful except in the late stages and where sinus tracts are about to emerge onto the skin surface. Dissemination from the initial site is exceptionally rare, although local lymphadenopathy may occur.

X-ray changes include periosteal erosion and proliferation, as well as the development of lytic lesions in the bone. Bone scans or magnetic resonance imaging may identify bone lesions at an earlier stage.

Chronic bacterial or tuberculous osteomyelitis may resemble mycetoma. Actinomycosis (see Chapter 185) is also similar but usually develops close to certain sites, such as the mouth or the cecum, where the causative organisms are sometimes commensal.

Finding the mycetoma grains is the key to establishing the diagnosis, and these are generally discharged from the openings of sinus tracts. However, they may also be obtained by removing the surface crust from a pustule or sinus tract with a sterile needle and gently squeezing the edges. Grains are 250–1,000-μm white, black, or red particles that can be picked out with the naked eye (Table 190-1). Direct microscopy of grains is important because it will show whether the grain is composed of the small actinomycete or broader fungal filaments. In general, it is not possible to distinguish the fine actinomycete filaments in potassium hydroxide (KOH) mounts or, for that matter, in hematoxylin and eosin-stained material. In addition, black grains are always caused by fungi; red grains, by actinomycetes (see Table 190-1).

Organisms | Hematoxylin and Eosin Section Appearances |

|---|---|

Eumycetoma | |

Dark grains | |

Madurella mycetomatis | Cement present, vesicles sometimes prominent |

M. grisea | Cement absent, compact outer layer |

Leptosphaeria senegalensis | Cement in outer zone, dark periphery with vesicular center |

Exophiala jeanselmei | Cement absent, often hollow |

Pyrenochaeta romeroi | Cement lacking, compact outer layer |

Pale grains | |

Fusarium sp., Acremonium, Scedosporium apiospermum, Aspergillus nidulans, Neotestudina rosati | Compact, pigment lacking, interwoven fungal filaments (Scedosporium apiospermum may have prominent vesicles) |

Actinomycetoma | |

Pale (white to yellow) grains | |

Actinomadura madura | Basophilic-stained fringe in layers |

Nocardia brasiliensis | Small, pale blue, eosinophilic fringe |

Yellow to brown grains | |

Streptomyces somaliensis | Grains fractured, basophilic, or pink |

Red to pink grains | |

A. pelletieri | Small, basophilic layers |

Final identification requires isolation of the causal agent in culture. In view of the number of possible species, a series of different culture media and conditions of incubation should be used. Morphologic and physiologic characteristics are used to distinguish between the genera and species. There are now a few examples where the organism has been identified using specific primers through use of the polymerase chain reaction. Serology is diagnostically helpful only in some cases (e.g., in S. somaliensis), and even then, more as a guide to therapeutic response. In a few centers, molecular tools are used to identify organisms.

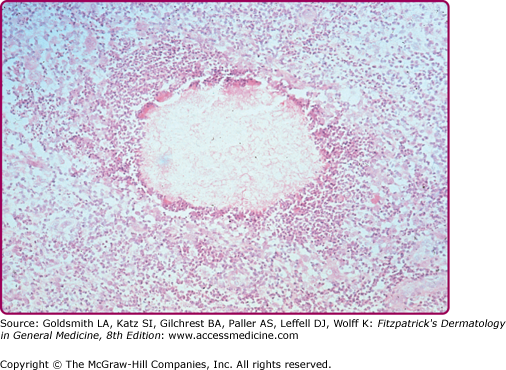

Histologically, there is a chronic inflammatory reaction with neutrophil abscesses and scattered giant cells and fibrosis.11 Grains are found in the center of the inflammation. Their size and shape may help in the identification, although with nonpigmented (pale or white grain) eumycetomas, this is seldom sufficient (Fig. 190-5).

Of the fungal causes of mycetoma, some cases of M. mycetomatis infection respond to ketoconazole, 200 mg, itraconazole 200 mg or voriconazole 200–400 mg daily over several months. For the others, a trial of therapy with griseofulvin, or terbinafine, is worth attempting. However, responses to chemotherapy are unpredictable, although antifungals may slow the course of infection. Surgery, usually amputation, is the definitive procedure and may have to be used in advanced cases. However, the value of major surgery in a disfiguring but nonlife-threatening infection has to be weighed against the availability of appropriate prosthetic limbs.

Actinomycetomas (see Chapter 185) generally respond to antibiotics such as a combination of dapsone with streptomycin or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim plus rifampin or streptomycin. Amikacin or imipenem also may be used in recalcitrant Nocardia infections. The responses in all but a few cases are good.15

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues caused by pigmented (dematiaceous) fungi that are implanted into the dermis from the environment. In the ensuing inflammation, they form thick-walled single cells or cell clusters (sclerotic or muriform bodies), and these may elicit a marked form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia often accompanied by transepidermal elimination of organisms. The infection can be caused by a number of different pigmented fungi, the most common being Phialophora verrucosa, Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Fonsecaea compactum, Wangiella dermatitidis, and Cladophialophora carrionii.16

The fungi that cause chromoblastomycosis can be isolated in the environment from wood, plant debris, or soil.17 The vast majority of infections are caused by F. pedrosoi and C. carrionii. As with other subcutaneous mycoses, infection follows implantation through a tissue injury. The infection is found as a sporadic condition in Central and South America, although rarely in North America. It occurs in the Caribbean region, Africa (particularly Madagascar), Australia, and Japan. It also may occur as an imported infection outside the usual endemic areas. The disease is most frequent in male rural workers.

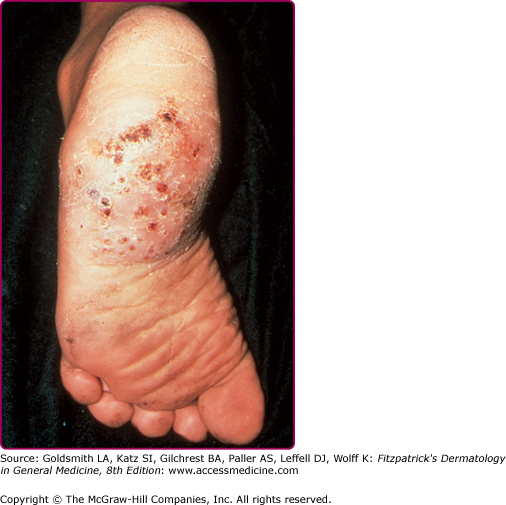

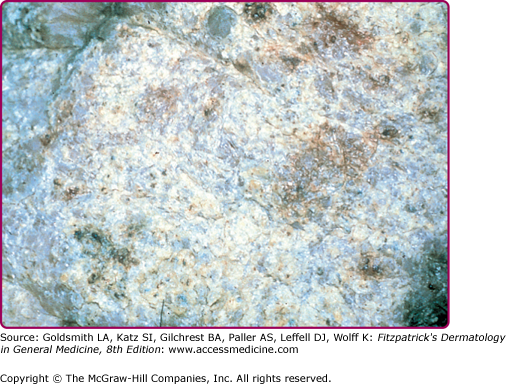

The initial site of the infection is usually on the feet, legs, arms, or upper trunk. The clinical features vary.17 The initial lesion is often a warty papule that expands slowly over months or years (Figs. 190-6 and 190-7). Alternatively, lesions may be plaque-like with an atrophic center. The more common verrucous form spreads slowly and locally. Individual lesions may be very thick and often develop secondary bacterial infection. Satellite lesions around the initial site of infection are local extensions of the infection and usually are produced by scratching. Complications of chromoblastomycosis include local lymphedema, leading to elephantiasis and squamous carcinomas in some chronic lesions.

The disease must be differentiated from podoconiosis or chronic tropical lymphedema with hyperplasia (mossy foot) which is due to a reaction to soil microparticles. Other chronic verrucous lesions, such as tuberculosis and blastomycosis, are often more extensive. The identification of organisms in the lesions of chromoblastomycosis is essential.

The typical sclerotic or muriform fungal cells can be seen in skin scrapings taken from the surface of lesions, particularly areas where there is a small dark spot on the skin surface, using KOH mounts. The lesions also should be biopsied because the pathologic changes and presence of muriform cells are typical. The histology shows a mixed granulomatous response, with small neutrophil abscesses and often exuberant epidermal hyperplasia.18 The organisms, which are often seen either in giant cells or in neutrophil abscesses, appear singly or in small groups of brown pigmented cells, often with a single or double septum and thick cell wall.

In culture, these fungi are very similar in gross macroscopic appearance, producing black colonies with a downy surface. Their cultural identification depends on demonstrating the presence of different but specific types of sporulation, and either single or multiple sporulation mechanisms may be seen in each organism. Accurate differentiation between the different fungi may be difficult. At this stage, the choice of treatment does not depend critically on correct identification of the organisms, although there may be differences in the speed of response to azole drugs (see Section “Treatment”).

The main treatments for chromoblastomycosis are itraconazole, 200 mg daily;19 terbinafine, 250 mg daily;20 and, in extensive cases, intravenous amphotericin B (up to 1 mg/kg daily). Lesions can be spread by surgery, which should be used only as an adjunctive therapy after drug treatment. The local application of heat may be helpful in some instances. The responses of these fungi to different antifungal agents do not appear to differ significantly, although there is some evidence that C. carrionii responds more rapidly to terbinafine and itraconazole. In any event, treatment is continued until there is clinical resolution of lesions, which usually takes several months. Extensive lesions often respond poorly to conventional treatment and combinations of antifungal drugs have been used, for example, amphotericin B and flucytosine or itraconazole and terbinafine.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare infection characterized by the formation of subcutaneous inflammatory cysts or plaques. It is caused by dematiaceous fungi, the most common of which are Exophiala jeanselmei and W. dermatitidis, but some 103 species have been described as causal agents.21 However, unlike in chromoblastomycosis, these organisms form short, irregular, pigmented hyphae in tissue. The infection may occur in any climatic area, although it is more common in the tropics. It also may appear in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those receiving long-term glucocorticoid therapy. The lesions present as cysts and may be mistaken for other similar structures such as synovial or Baker’s cysts. The diagnosis is usually made after surgical excision. Histologically, the cyst wall consists of palisades of macrophages and other inflammatory cells surrounded by a fibrous capsule, and the fungal hyphae are found in the macrophage zone. Although the fungi in tissue lesions are usually pigmented, this is not always the case; cystic lesions caused by nonpigmented fungi being called hyalohyphomycotic cysts. The treatment is surgical excision, although relapse can occur, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Lobomycosis is an uncommon infection seen in Central and South America, often in remote rural areas. The source of the organism is unknown, although similar lesions have been found on freshwater dolphins. Lobomycosis is characterized by the appearance of keloid-like skin lesions on exposed sites.22 Although it cannot be cultured in vitro, it is caused by a fungus, Lacazia loboi, that forms chains of rounded cells in tissue, each joined by a small tubule. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body but usually are found on exposed parts such as the legs, arms, and face. They can spread from site to site by autoinoculation. Antifungal drugs are not effective, and surgical removal is the main treatment.

Subcutaneous Mucormycosis [Basidiobolomycosis, Subcutaneous Phycomycosis and Conidiobolomycosis, (Rhino)-Entomophthoromycosis]

Subcutaneous mucormycosis is a rare tropical subcutaneous mycosis characterized by the development and spread of a chronic, firm swelling involving subcutaneous tissue. There are two main varieties caused by different organisms.23 The first, most often caused by Basidiobolus ranarum (B. haptosporus), is more common in children. It occurs in a wide variety of countries and environments from South America to Africa and Indonesia. The organism can be found in plant debris and in the intestinal tracts of reptiles and amphibians. Lesions usually develop around limb girdle sites and present with a firm, slowly spreading, woody cellulitis. The second form, caused by Conidiobolus coronatus, is seen in adults. The organism can be isolated from soil, plant debris, and some insects. The early infection starts in the region of the inferior turbinates of the nose. Spread involves the central part of the face, and once again, the swelling is hard and painless. It may cause very severe deformity of the nose, lips, and cheeks. These infections are distinct to those caused by related fungi.

Histopathologically, a chronic granulomatous response with large numbers of eosinophils can be seen. The fungi are present as large, strap-like hyphae without cross walls or septa. They are also often surrounded by refractile eosinophilic material (Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon). The organisms can be cultured readily on Sabouraud’s agar. Ketoconazole (400 mg daily) and itraconazole (100–200 mg daily) also may be useful in this condition, although experience to date is limited to a few cases. Lesions also respond to oral treatment with potassium iodide, given in similar doses to those used in sporotrichosis (see Section “Treatment” under “Sporotrichosis”).

Rhinosporidiosis is a chronic infection caused by the organism Rhinosporidium seeberi, which causes the development of polyps affecting the mucous membranes. The organism has never been cultured, and it is now thought to be an aquatic protist and a member of the Mesomycetozoea. Rhinosporidiosis is seen most often in Southern India and Sri Lanka. Cases also have been described in South America, the Caribbean, and South Africa. Exposure to water (lakes, pools) has been associated with the infection. The main site affected is the nasal mucosa, but the conjunctival mucosa also may be affected.24 The infection causes the development of polyps that are studded with white flecks; these are small cysts or sporangia containing small spores. These are best seen in histopathologic sections, where the large sporangia or spore sacs in different phases of development are readily seen. The only treatment is surgical excision.

Systemic Mycoses

|

The systemic mycoses are fungal infections whose initial portal of entry into the body is usually a deep site such as the lung, gastrointestinal tract, or paranasal sinuses. They have the capacity to spread via the bloodstream to produce a generalized infection. In practice, there are two main varieties of systemic mycosis: (1) the opportunistic mycoses and (2) the endemic respiratory mycoses.

The chief opportunistic systemic mycoses seen in humans are systemic or deep candidiasis, aspergillosis, and systemic zygomycosis. These affect patients with severe underlying disease states, such as AIDS, or with neutropenia associated with malignancy, solid-organ transplants, or extensive surgery. With the use of combination antiretroviral therapy, the incidence of systemic mycoses in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has dropped considerably. In the neutropenic patient in particular, other fungi also may cause infection occasionally. Different underlying conditions predispose to different mycoses, and a scheme for this is shown in Table 190-2. Generally, skin involvement is not common with most of these opportunistic infections, which can occur in any climate and environment. The clinical manifestations of the opportunistic mycoses are also variable because they depend on the site of entry of organism and the underlying disease.

Predisposition | Infection |

|---|---|

Neutropenia (whatever cause) functional neutrophil defects | Aspergillosis, oropharyngeal, and/or systemic candidiasis, mucormycosis, infections due to rare organisms |

CD4 lymphopenia (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) | Oropharyngeal candidiasis, cryptococcosis, and endemic respiratory mycoses such as histoplasmosis, nocardiosis |

Diabetes mellitus | Mucormycosis |

Heart valve surgery | Various but mainly Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida sp. |

Abdominal surgery | Candidiasis |

The endemic respiratory mycoses are histoplasmosis (classic and African types), blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and infections due to Penicillium marneffei. The clinical manifestations of these infections are affected by the underlying state of the patient, and many develop in the presence of particular immunodeficiency states, notably AIDS. However, they follow similar clinical patterns in all infections. These infections also may affect otherwise healthy individuals. They have well-defined endemic areas determined by factors that favor the survival of the causative organisms in the environment, such as climate. The usual route of infection is via the lung (Fig. 190-8).