Decubitus (Pressure) Ulcers: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Estimates are that between 1.5 and 3 million people in the United States have pressure ulcers. Hospital stays with pressure ulcers listed as a diagnosis increased by nearly 80% in the United States between 1993 and 2006. These chronic wounds cost approximately $5 billion annually to treat, and Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) no longer reimburses for additional costs arising from nosocomial stage III or IV pressure ulcers.1–6

The prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers varies with the clinical setting. In acute care, the incidence ranges from 0.4% to 38%; in long-term care, from 2.2% to 23.9%; and in home care, from 0% to 17%. Most pressure ulcers develop during the first few weeks of hospitalization. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in acute care settings is approximately 15%, in long-term care settings from 2.3% to 28%, and in home care from 0% to 29%.1–4

Pressure ulcers are more common in the elderly, especially those over the age of 70, in patients who have had surgery for hip fracture, and in patients with spinal cord injury. A multicenter study of 3,233 elderly admitted from the emergency demonstrated a pressure-ulcer incidence (mostly stage II) of 6.2% on hospital day 3, with significant associations to advanced age, male gender, dry skin, urinary and fecal incontinence, difficulty turning in bed, and poor nutritional status.7

Etiology and Pathogenesis

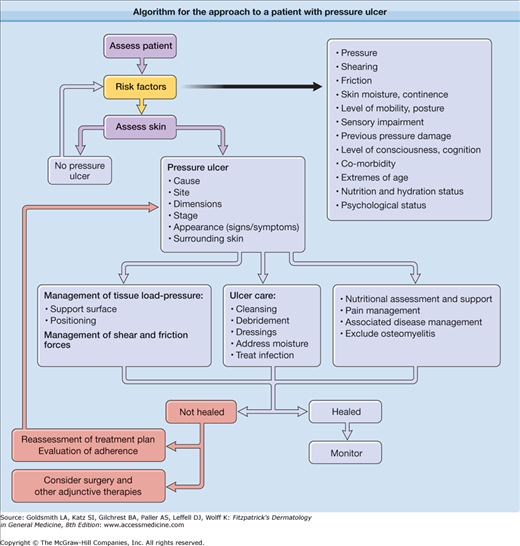

The main etiologic factors contributing to pressure ulcer development include pressure, shearing forces, friction, and moisture.

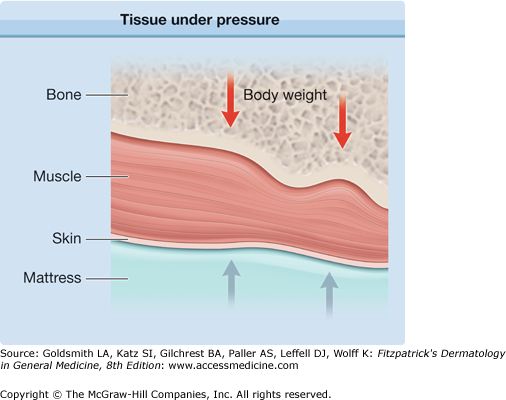

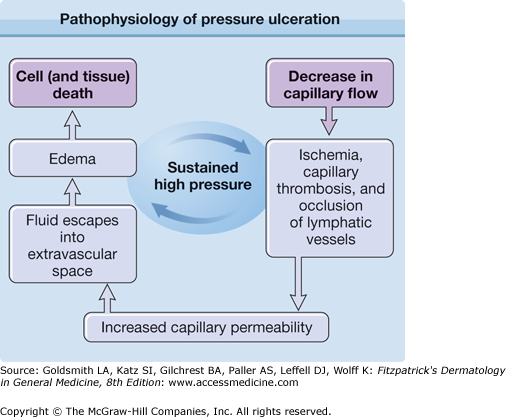

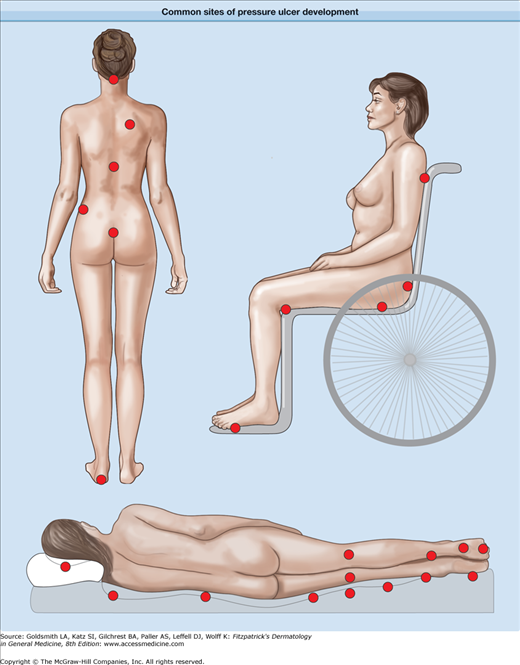

Pressure or force per unit area is considered to be the most important factor in pressure ulcer formation. Normal tissue pressure is between 12 and 32 mm Hg. Pressures higher than this upper limit can compromise tissue circulation and oxygenation. When a patient lies immobile on a hospital bed, pressures as high as 150 mm Hg can be generated, especially over bony prominences. At pressures of 70 mm Hg or more, there is an inverse time–pressure curve with rapid pressure ulcer formation.2 Sitting positions can also generate elevated pressure over precise body surfaces. The duration as well as degree of pressure is important. If pressure is relieved regularly, tissue recovery can occur, whereas constant pressure can lead to tissue death (Fig. 100-1). Often, damage occurs deep at the bone–muscle interface, in which the limited cutaneous injuries may be only the “tip of the iceberg” of deeper, more extensive damage (eFig. 100-1.1). Patients who are immobile should therefore be turned regularly to prevent pressure ulceration. The pathophysiology of pressure ulcer formation is summarized in eFigure 100-1.2, and common sites of pressure ulcers are shown in Figure 100-2.

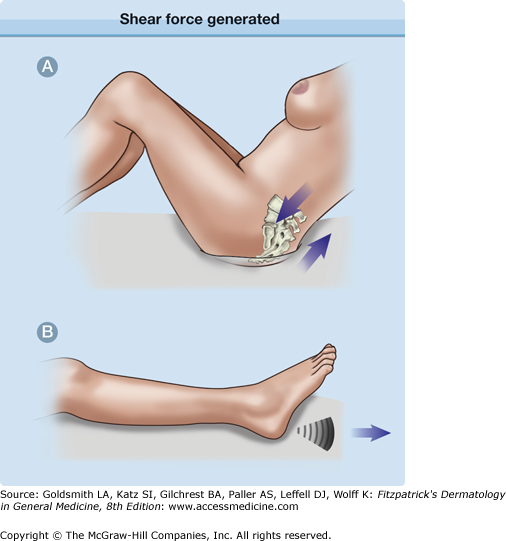

Shear force results from the motion of bone and subcutaneous tissues relative to the skin when the skin is fixed (e.g., when the upper body of a supine patient is raised to an angle above 30° and the skin remains in contact with the bed). Shearing forces are parallel to the tissue surface, and the subsequent sliding pressure is transmitted to deeper tissues, which can become angulated and occlude the blood vessels (Fig. 100-3A). Spinal cord injury patients develop such shearing forces with muscle spasms, which may be controlled with muscle relaxants.8

Friction is the force that resists the relative motion between two surfaces that are in contact. This causes damage to the superficial layers of the skin (e.g., when a patient is dragged across the bedsheets) (Fig. 100-3B).

A moist environment from urinary or fecal incontinence, perspiration, or excessive wound drainage can cause maceration of the skin, which increases the risk of pressure ulcer formation fivefold (Fig. 100-4). Other risk factors for pressure ulcer development include prolonged immobilization, sensory deficit, circulatory disturbances, poor nutrition, acute illness, advanced age, and a previous history of pressure ulcers as well as fecal and urinary incontinence, hip fractures, smoking, and dry skin. Concomitant use of medications such as corticosteroids, which can impair healing; sedatives and analgesics, which can impair consciousness; and drugs that can cause alterations in cutaneous blood flow, such as antihypertensive medications, can also increase pressure ulcer risk, and such drugs should be used with care (Table 100-1).

Alteration in sensation or response to discomfort

|

Alteration in mobility

|

Significant changes in weight (≥5% in 30 days or ≥10% in previous 180 days)

|

Incontinence

|

Clinical Findings

History taking and physical examination for pressure ulcer patients should incorporate a risk assessment scale. A number of risk assessment tools have been devised in an attempt to identify persons at risk for pressure ulcers. The Braden, Waterlow, and Norton scales have been extensively tested for reliability and validity and have been recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for predicting the risk of developing pressure sores. Currently, best practices in acute care, long-term care, and home-health care dictate that such risk assessments be performed initially at admission and at subsequent precise intervals. Components of these scales assess the following risk factors: mobility, activity level, nutritional status, mental status, incontinence/moisture conditions, general physical condition, skin appearance, medication use, friction and shear, weight, age, predisposing diseases, and prolonged pressure (eTable 100-1.1).

Risk Factor | Norton | Waterlow | Braden |

Mobility | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Activity level | Yes | No | Yes |

Nutritional status | No | Yes | Yes |

Mental status | Yes | No | Yes |

Incontinence/moisture conditions | Yes | Yes | Yes |

General physical condition | Yes | Yes | No |

Skin appearance | No | Yes | No |

Medication | No | Yes | No |

Friction and shear | No | No | Yes |

Weight | No | Yes | No |

Age | No | Yes | No |

Specific predisposing diseases | No | Yes | No |

Prolonged pressure | No | Yes | No |

Staging is an assessment system that classifies pressure ulcers based on anatomic depth of soft-tissue damage. Pressure ulcers often progress from lower to higher stages, and any small pressure ulcer should be considered as the possible “tip of an iceberg.” Table 100-2 shows the clinical appearance of pressure lesions and ulcers and their histopathologic correlates as defined by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). Palpation is important to assist visual evaluation. Ulcers that initially appear superficial can end up being classified as stage III or IV after débridement reveals their true depth. The epidermis may be hypertrophic at the ulcer margin with varying degrees of pigmentation.10

Classification/Stage9 | Clinical Findings | Histopathologic Description |

|---|---|---|

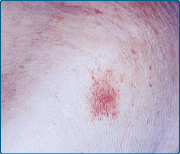

Stage I

| Nonblanchable erythema of intact skin | Epidermis appears normal. Striking red blood cell engorgement of capillaries and venules, mainly in papillary dermis with platelet thrombi and hemorrhage. Degeneration of sweat glands and subcutaneous fat is often seen. |

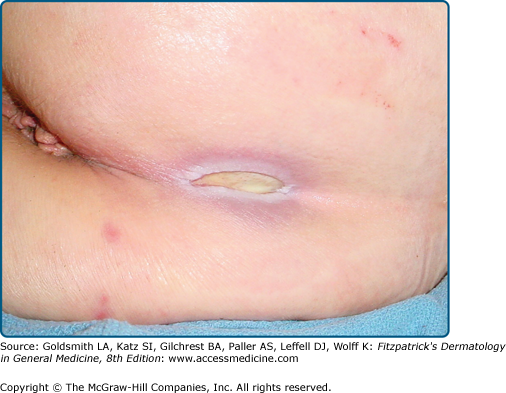

Stage II

| Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both | Epidermis is lost. Dermal papillae are often identifiable. Acute inflammation of papillary and reticular dermis is found. In addition to a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, neutrophils are seen. Necrotic changes in the appendages and fat are more pronounced. |

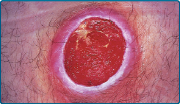

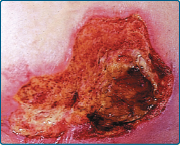

Stage III

| Full-thickness skin loss involving damage to or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, underlying fascia. | Hemorrhagic crust containing acute inflammatory cells or a thin zone of coagulation necrosis on the surface. Diffusely fibrotic dermis. Loss of appendageal structures. |

Stage IV

| Full-thickness skin loss with extensive necrosis of or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures. | Full-thickness destruction of skin. The tissue appears basophilic with obliteration of cellular detail, although the general dermal architecture is preserved. Inflammatory infiltrate is often not seen. |

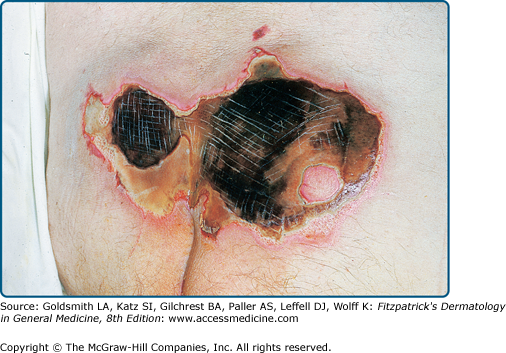

There are several staging systems for classifying pressure ulcers. The most commonly used include the NPUAP, Shea, and Yarkony et al systems. In February 2007, the NPUAP redefined the stages of pressure ulcers established in 1989 by preserving the four original stages and adding two new stages of deep tissue injury and unstageable pressure ulcers. The unstageable category was created to avoid unnecessary removal of slough or eschar simply for the purpose of staging, which might hinder ulcer healing (Fig. 100-5). eTable 100-2.1 compares these four classification systems.2,10–13

Classification | Shea (1975)9 | NPUAP (1989) | Yarkony and Kirk (1990)7 | NPUAP (2007) |

Suspected deep tissue injury | Purple/maroon “bruise” or blood-filled blister | |||

Stage I | Limited to epidermis, exposing dermis | Nonblanchable erythema of intact skin | Red area A. Present >30 minutes but <24 hours B. Present longer than 24 hours | Nonblanchable erythema of intact skin |

Stage II | Full thickness of dermis to junction of subcutaneous fat | Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both | Epidermis and/or dermis ulcerated with no subcutaneous fat observed | Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, or both |

Stage III | Fat obliterated, limited by deep fascia undermining of skin | Full-thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend to, but not through, underlying fascia | Subcutaneous fat observed, no muscles observed | Full-thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend to, but not through, underlying fascia |

Stage IV | Bone at the base of ulceration | Full-thickness skin loss with extensive necrosis of or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures | Muscles observed, but no bone observed | Full-thickness skin loss with extensive necrosis of or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures |

Stage V | Close large cavity through a small sinus (closed pressure ulcer) | — | Bone observed but no involvement of joint space | |

Stage VI | In joint spaces | |||

Unstageable | — | — | Full-thickness skin loss obscured by slough or eschar over the base of the wound |

All pressure ulcer patients should undergo a full physical examination to identify systemic disease contributing to wound development, such as anemia, chronic cardiac or respiratory disease, and neurologic disorders.

Tenderness, erythema, edema and warmth of surrounding skin, exudate, and foul odor are symptoms and signs of infection. Fever and declining mental or physical status should raise suspicion of bacteremia or osteomyelitis.

Spasticity secondary to inflammation and infection may trigger muscle contractures and joint deformity that can limit motion, which complicates positioning. Weakness and signs of anemia and dehydration can be found secondary to profound loss of fluid and protein from these open, draining wounds.