Debridement of Soft Tissue Infections of the Lower Leg

L. Scott Levin

Paulo Piccolo

DEFINITION

The term debridement was coined by Joseph Pierre DeSault in the 18th century. The French term implies the removal of soft tissues and bone that are nonviable, with the goal of preventing infection. It is defined by the Oxford medical dictionary as the process of cleaning an open wound by removal of foreign material and nonviable tissue, so that healing may occur without hindrance.1

By removing molecular, physical, and microbiologic barriers to healing, debridement facilitates endogenous wound healing.

ANATOMY

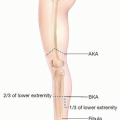

The lower extremity consists of four major regions: the hip, thigh, leg, and foot. It is specialized for support of body weight, adaptation to gravity, and locomotion.

The thigh is divided in three compartments (anterior, posterior, and medial), and the leg is divided in four compartments (anterior, deep, superficial posterior, and lateral).

PATHOGENESIS

Wounds may originate through a variety of causes, such as soft tissue infection (acute or chronic), trauma (thermal, electric, chemical, penetrating, or blunt), vascular issues (arterial, venous, or lymphatic), neuropathic (eg, diabetes), or malignancy.

The pathogenesis of the wound will play a key role in the treatment plan. A wound from necrotizing fasciitis needs emergent attention and wide debridement, as opposed to one caused by venous stasis, which can be dealt with in an ambulatory setting and may be amenable to a more conservative treatment approach.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history of present illness must be obtained. This is paramount in establishing the cause, timing, and clinical implications of that wound, the potential level of disability caused by it, and to plan further treatment.

Patient’s comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, surgical history, nutritional status, previous trauma and, nicotine use should all be taken into account.

A thorough physical exam of the extremity in question must be performed preoperatively, and many times, it should be completed in the operating room under anesthesia to minimize patient’s discomfort and allow for a precise and thorough analysis of the area.

Nerve integrity must be assessed before the patient is under anesthesia—both motor and sensory aspects must be checked from the proximal thigh to the distal toe.

Peripheral pulses are of extreme importance when treating lower extremity wounds, as this will give vital information regarding limb perfusion, wound pathogenesis, and options for future reconstruction.

Size and appearance of the wound, characteristics of the surrounding soft tissue, and skeletal stability of the extremity should also not be overlooked. The presence of exposed vital structures, including nerves, vessels, bones, and joints, must be appreciated and well documented on the patient’s chart. The presence of foreign body on the wound bed must be ruled out (eg, a chronic wound caused by a retained piece of packing/dressing material).

IMAGING

Preoperative imaging studies are not always mandatory but often provide valuable information to the reconstructive surgeon.

Plain films are important to assess proper bony alignment in the setting of trauma or in acute infections to quickly assess for the presence of subcutaneous gas.

Computed tomography (CT) with the aid of intravenous contrast (computed tomography angiography [CTA]) may determine proper vascularization to the extremity when there is any question regarding distal blood flow, be that acute or chronic.

Bone scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess for bone viability or osteomyelitis are important adjuncts when planning for debridement of a lower extremity wound with exposed bone.

Other imaging modalities may aid the operating surgeon in evaluating vascularity of the bone such as PET scans.2

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The decision to perform a surgical debridement of a lower extremity wound lies in the hands of the reconstructive surgeon.

Before the era of free tissue transfer, debridement was often limited because removing questionable tissue could lead to exposure of vital structures, such as tendon devoid of paratenon, vessels, or nerves, and bone devoid of the periosteum. Surgeons were reluctant to make the traumatic defects larger by radical debridement. Subsequently, surgical techniques were more conservative, and healing by secondary intention with wound contracture, scar, and unstable soft tissues was the rule. Currently, free tissue transfer using large well-perfused flaps facilitates radical debridement and necrectomy (removal of dead tissue).

Preoperative Planning

General anesthesia is preferred. If patient is not a suitable candidate for general anesthesia due to comorbidities, spinal anesthesia or regional block can be considered.

As mentioned previously, a more thorough physical exam can be performed with the patient under anesthesia.

Debridement should be performed with the use of the tourniquet. The tourniquet is inflated to 350 mm Hg after an Esmarch bandage is used to exsanguinate the limb. In cases of malignancy or infection, the use of the tourniquet is contraindicated. In these cases, elevating the leg for 5 minutes before inflating the tourniquet aids in limb exsanguination.

In an ischemic operative field, it is simpler to distinguish between healthy and damaged tissues. The basic elements of this judgment are the appearance and consistency of the tissues. Healthy tissue in the exsanguinated field is bright and homogeneous in color. Subcutaneous tissue is yellow, muscles are bright red, and the tendons and fascia have a white and shiny appearance.

Damaged tissues are recognized by the presence of foreign bodies, irregular tissue consistency, and irregular distribution of dark red stains, caused by hematomas or hemosiderin (FIG 1).

Evaluating muscle viability may propose a challenge in some cases. Classically, the so-called 4 Cs—muscle color, consistency, contractility, and capacity to bleed—are generally used to assess muscle viability and guide debridement. Recent studies, however, show a potential tendency for normal muscle resection3 as the surgeon’s impression of muscle viability does not correlate with histological findings of the debrided muscle in the majority of cases. Therefore, when large amounts of muscle appear of questionable viability in the first stage of debridement, a second trip to the operating room may be necessary to avoid over resection of viable muscle. This is in contrast with clearly necrotic muscle, which will be discussed further.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree