Cutaneous Changes in Peripheral Venous and Lymphatic Insufficiency: Introduction

|

Chronic Venous Disease

Chronic disease of the peripheral veins includes a spectrum of diseases ranging from edema and tenderness to venous ulceration (Box 174-1).

SYMPTOMS

SIGNS Very Early

Early

Late

|

Veins are thin-walled, distensible, and collapsible structures that function to transport blood toward the heart and act as a reservoir for preventing intravascular volume overload. Microscopically, veins consist of an intima, media, and outer collagenous adventitia. All peripheral veins contain endothelium lined, semilunar, venous valves, which promote unidirectional blood flow toward the heart. Vascular endothelium is described in detail in Chapter 165 and the anatomy of the venous system of the lower extremities is described in Chapter 249.

Chronic venous disease is extremely common. Although estimated costs and time lost from work have not been objectively assessed in over two decades, estimates state that 6–7 million people in the United States have evidence of venous stasis and that it accounts for 1% to 3% of the total health care budgets in countries with developed health care systems.1

Risk factors for chronic venous disease include heredity, age, female sex, obesity, pregnancy, prolonged standing, and greater height.2

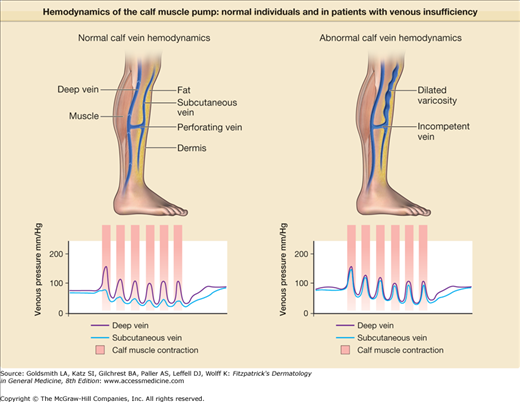

Venous ulcer occurs after failure of the calf muscle pump (Fig. 174-1). The heart pumps blood down to the foot; the calf muscle pump (when upright), returns venous blood to the heart. Venous blood from the skin and subcutis collects in the superficial venous system including the greater and lesser saphenous veins and its tributaries, moves through the fascia in a series of “perforating” or “communicating” veins, and fills the muscle-enveloped deep venous system. With muscle contraction, the deep veins are compressed; one-way valves in the deep system allow the now high pressure flow to move against gravity, and one-way valves in the perforators close to prevent pressure injury in the skin (see Fig. 174-1). In all patients with venous disease there is failure of these one-way valves and this can result in varicose veins (Fig. 174-2). The severity of venous disease is influenced by the number and distribution of incompetent valves and is worsened by any impairment of leg muscle function or ankle joint range of motion—all critical components of the calf muscle pump. Any obstruction to venous return (thrombosis, radiation fibrosis, etc.), or elevation of right atrial pressure (pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, etc.), further compromises venous return. A more detailed description of the anatomy and hemodynamics of the venous system of the lower extremities is found in Chapter 249.

The most common cause of valvular failure is thrombosis. The nidus for venous thrombosis is typically the valve cusp, and when the thrombus is lysed by plasmin, valve function is often lost as well. Calf muscle pump failure after deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is often referred to as the postphlebitic syndrome.3

Once valves fail, especially those in the perforators, high pressure blood in the deep system refluxes into the unsupported veins of the skin, there is vascular leakage of fibrinogen producing “fibrin cuffs” that may interfere with tissue nourishment, and white blood cell trapping leading to soft tissue injury, inflammation, and eventually fibrosis, as the subcutaneous fat is replaced by scar in a process described by the term lipodermatosclerosis (see Section “Cutaneous Lesions”).

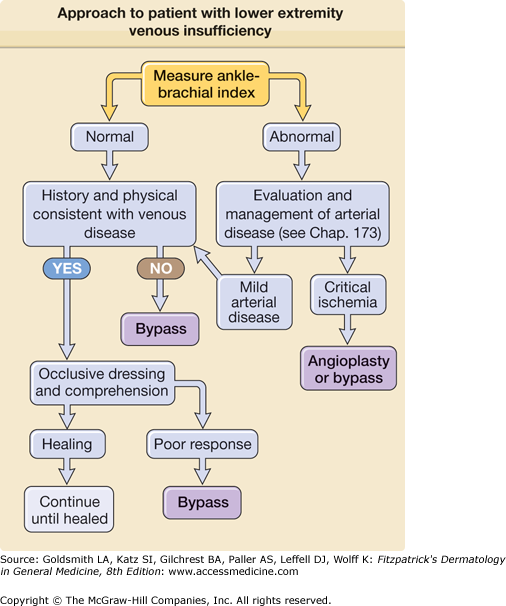

An approach to the analysis of patients with ulcers is in Fig. 174-3.

Trauma frequently triggers the nonhealing venous ulcer. The events preceding ulceration happen insidiously over many years and may be ignored by the patient. A history of thrombosis may be missing because most episodes of lower extremity venous thrombosis are clinically silent. Relevant inquiry related to thrombosis risk should include a family history of similar problems (suggesting perhaps a familial thrombotic tendency), any episode of leg immobilization including knee or hip surgery and fractures, and any head injury associated with loss of consciousness.

Most patients complain of leg swelling, and many have been given diuretics, though the edema of venous disease, unlike the edema in salt-retaining states, like heart failure, cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome, does not respond to diuretics. An edematous leg not responsive to diuretic therapy is a strong clue to the diagnosis. Venous ulcers may or may not be painful.

All of the clinical syndromes described are secondary to the initial valvular syndrome and are grouped into clinical categories. Once there is venous valvular failure, a rather predictable series of changes occur in the skin. The earliest (though not universal) physical finding is soft tissue tenderness, even of normal appearing skin, discovered when checking for the presence of edema by palpation. Its association with other cutaneous signs of chronic venous disease is common.

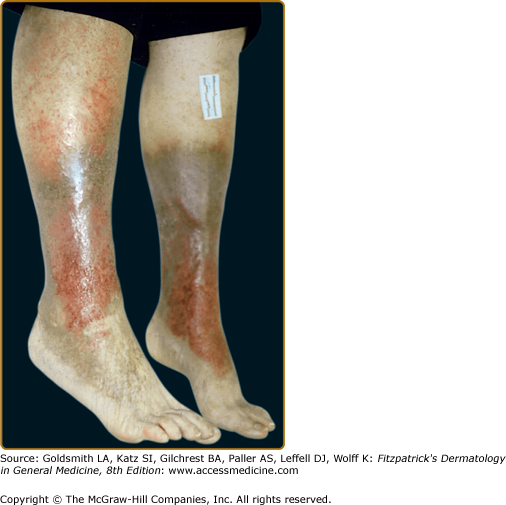

The soft tissue injury that precedes ulceration begins in the subcutis, and visible changes may not appear for some time. Frequently one notes the appearance of petechial lesions, which have the appearance of cayenne pepper sprinkled about the gaiter area. As the hemoglobin in the petechial lesions breaks down, the iron remains in the skin as hemosiderin and may lead to impressive discoloration (Fig. 174-4).

Stasis dermatitis, characterized by erythema, scaling, pruritus, erosions, oozing, crusting, and occasional vesicles may occur during any stage of chronic venous insufficiency (see Fig. 174-4). It typically occurs in the medial supramalleolar region where microangiopathy is most intense. Over time, lesions may lichenify. As 58% to 86% of patients with venous leg ulcers develop contact sensitization to topical therapies, it is important to evaluate for coexisting allergic contact dermatitis.

In lipodermatosclerosis (sclerosing panniculitis, hypodermatitis sclerodermiformis) pliable subcutaneous fat is gradually replaced by fibrosis, and the skin begins to feel indurated. This is a fibrosing panniculitis (see Chapter 70) characterized by a bound-down, indurated plaque that begins at the medial ankle and extends circumferentially around the entire leg.4 As the fibrosis increases, it may constrict and strangle the lower leg further, impeding venous and lymphatic flow and leading to brawny edema above and below the fibrosis. These late changes resemble an inverted champagne bottle (Fig. 174-4).

Varicose veins, especially noticeable when the patient is standing, and smaller varicosities appear about the dorsum of the foot and ankle (see Chapter 249). Although they are usually asymptomatic, patients may complain of symptoms of aching, cramping, itching, fatigue, and swelling that are worse with prolonged standing.

Atrophie blanche refers to skin overlying areas of fibrosis that often appears porcelain white and atrophic. Fully established lesions of atrophie blanche consist of irregular, smooth, atrophic plaques with surrounding hyperpigmentation and telangiectasias (Fig. 174-5). Although mostly related to venous stasis, atrophie blanche may also be associated with an underlying disorder of coagulation (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome, inherited coagulopathies) livedoid vasculitis (see Chapter 163) or autoimmune disease (e.g., scleroderma, lupus erythematosus).5 Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma, congenital dysplastic angiopathy, arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis) has purple macules, nodules, or verrucous plaques on the dorsal feet and toes of patients with long-standing venous insufficiency and mimics Kaposi sarcoma clinically and histologically. Identical lesions have been described in arteriovenous malformations of the legs, arteriovenous shunts for hemodialysis, paralyzed limbs, and amputation stumps (.

Occasionally, acute inflammation of the subcutaneous fat develops in patients with venous disease, and histologically one finds an acute septal panniculitis in this setting (see Chapter 70).

Though ulceration is classically located in the gaiter area (see Fig. 174-6), venous ulcers have been described anywhere below the knee. Venous ulcers are typically tender, shallow, irregular, red-based ulcers that are always located below the knee (Figs. 174-6 and 174-7). They are usually located on the medial ankle or along the line of the long or short saphenous veins. Clinical distinction should be made with other common ulcers of the lower extremity as discussed later in this chapter and as shown in Box 174-2.

|

Histologic signs of venous hypertension include hemosiderin deposition, lobular superficial and/or deep dermal neovascularization, and fibrosis of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in later stages. These histologic findings are found in all clinical manifestations of chronic venous disease.

It is crucial to evaluate arterial blood flow. A useful bedside screening test is to calculate the ratio of the systolic blood pressure in the ankle (as measured by Doppler) to the systolic pressure in the brachial artery (also measured by Doppler). This “ankle/brachial index” is greater than or equal to one in normal individuals. Anything less than one is an indication of peripheral arterial disease. The lower the ratio, the more severe the arterial obstruction (see Fig. 174-3). An ankle/brachial index is reliable except in the presence of calcified vessels, which are noncompressible and therefore a true systolic pressure cannot be measured. Having excluded arterial disease as a cause of ulceration, a clinical diagnosis is sufficient for the initiation of empiric therapy in most cases. When the diagnosis is in doubt, skin biopsy may be useful. Functional testing of calf muscle pump function and venous valvular function using plethysmography is occasionally useful. Duplex Doppler ultrasonography can be useful to document valvular incompetence and to evaluate patients for possible sclerotherapy or surgery (see Chapter 249).

Recurrent ulceration is frequent. Any open wound provides a portal of entry for bacteria, and cellulitis, though infrequent, may develop at any time. Given that venous dermatitis may be extremely pruritic, and that these patients are easily sensitized to the topical agents they apply, contact dermatitis, especially due to topical antibiotics, is common. The skin is easily excoriated and may become infected.6 The advent of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is a threat to this population. The dermatitis of venous disease may become generalized as an id reaction (see Chapter 17) and may rarely produce an exfoliative erythroderma (see Chapter 23). Many of these individuals are predisposed to thrombi, and recurrent episodes of venous thrombosis are not uncommon.

All patients with advanced venous disease have some degree of lymphatic impairment, though lymphatic impairment may also result from inherited defects in lymphatic development or destruction of lymphatics after cellulitis lymphangitis, surgical interruption, or radiation.7 Loss of lymphatic drainage from the lower leg may lead to verrucous changes and cutaneous hypertrophy, elephantiasis nostras (see Section “Acquired Lymphedema”).

The prognosis for healing areas of ulceration and inflammation is excellent in the absence of comorbid illness that interferes with healing. The vast majority of uncomplicated patients respond well to ambulatory outpatient therapy as outlined in the section “Treatment.” Permanent changes include hemosiderosis and fibrosis that develop before the initiation of therapy. Loss of valvular function is irreversible. In the absence of continual lifelong cutaneous support in the form of inelastic wraps or elastic stockings, skin and soft tissue injury continues.

Treatment of chronic venous insufficiency is outlined in Box 174-3. Treatment for all clinical manifestations of chronic venous insufficiency includes therapies that lower venous pressure and improve venous and lymphatic flow by mechanical means, dressings, drugs, and surgery.

|

Given the limitations of bed rest as an effective therapy, the focus is now on an ambulatory outpatient approach to the management of venous ulceration. Most experts agree on the essential role of compression in treating chronic venous insufficiency.8 Hence, unless there are contraindications (arterial occlusive disease or abnormal ankle–arm indexes), compression therapy should remain part of any treatment regimen for chronic venous disease.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Paul Gerson Unna recognized that by providing a compression bandage to the distal extremity he could heal venous ulcers in an ambulatory patient population using zinc impregnated gauze wrap, the “Unna boot.” Though the literature over the years continued to document the success of this approach, it proved difficult to achieve graduated compression with this wrap, and compliance was poor. Eventually, the addition of a self-adherent second layer (Coban™, for example) over a zinc wrap was introduced as the “Duke boot” and has proven to be easy to apply with reproducible graduated inelastic compression (Fig. 174-8) bandaging to counter the outflow from perforator incompetence is the cornerstone of venous ulcer management.9

In 1962, George Winter reported the use of an occlusive layer enhanced healing in a pig model of acute wounds. His data suggested a roughly 100% improvement in the rate of wound healing simply by providing a moist environment. The impact on wound care has been dramatic. There are now thousands of such dressings on the market and although they differ in composition, absorption, gas exchange, and cost, all provide a moist environment (see Chapter 248). Underneath such dressings, fibrinopurulent and necrotic debris, aided by host and bacterial enzymes, dissolves painlessly (eFig. 174-8.1). One can take advantage of these dressings to provide the best local environment for the wound, followed by a compression wrap to address the underlying hemodynamic disturbance.

The dressings should be changed weekly, or more often for heavily exudating wounds. New tissue is vulnerable to the cytotoxic effects of most topical antiseptics, and these agents are to be avoided. One should not put anything in a wound that you would not be willing to put in your eye. A gentle rinse with tap water or saline is sufficient. It is preferable to have the patient supine during dressing changes if at all possible.

Mechanical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for all clinical manifestations of chronic venous insufficiency. A Cochrane review found that “the use of elastic compression stockings to treat postthrombotic syndrome cannot be supported on the basis of the currently available data,” but did find some evidence for a beneficial effect for intermittent pneumatic compression units (http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2599/iedetect.aspx#2994643). Nevertheless, daily use of elastic compression stockings has been shown to reduce swelling in some patients with postthrombotic syndrome (http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2599/iedetect.aspx#2994644); prevent worsening of established postthrombotic syndrome (http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2599/iedetect.aspx#2994635); and may reduce recurrence of healed venous (ulcers http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2599/iedetect.aspx#2994645).

Each pharmaceutical therapy targets a specific clinical aspect of chronic venous insufficiency. Diuretics may be used in the short term for treating severe edema. Horse chestnut seed extract (often standardized to 50 mg escin twice daily) is an herbal remedy that appears to be safe and effective as a short-term treatment for leg pain and swelling.10 Aspirin (300–325 mg/day)11 and pentoxifylline12 may improve healing of chronic venous ulcers. Finally, topical steroids and emollients aid resolution of stasis dermatitis.

Although all wounds harbor potential pathogens, there is no evidence that routine use of antibiotics is helpful in patients with venous ulcer. If cellulitis is suspected, empiric therapy with coverage for S. aureus and Streptococci is warranted. Topical antibiotics, especially mupirocin, are useful for folliculitis due to S. aureus and Streptococci. With the increasing incidence of community acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus in this population, culture and sensitivity are suggested for suspected skin and soft tissue infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree