Cryosurgery, Cryobiology, and Croygens

Cryosurgery refers to the use of extreme cold to destroy cells of abnormal or diseased tissue. The earliest use of a cold refrigerant in medicine is attributed to White, a New York dermatologist, in 1899.1,2 Using a cotton-tipped applicator dipped into liquefied air, he successfully treated warts, nevi, and precancerous and cancerous lesions. In 1907, Whitehouse, another New York dermatologist, reported the utilization of the spray method in the cryosurgical treatment of skin cancers.3

Cryobiology refers to the study of the effects of subzero temperature on living systems. Tissue destruction from cryotherapy results from direct cell injury, vascular stasis, and the local inflammatory response.

Rapid freezing of cells causes intracellular ice crystal formation with the disruption of electrolytes and pH changes, whereas slow freezing causes extracellular ice formation and less cell damage. Therefore, tissue effects and cell death are most readily achieved when tissue is frozen rapidly.4

During thawing, recrystallization occurs when ice crystals fuse to form large crystals that disrupt cell membranes. As the ice melts further, the extracellular environment becomes hypotonic, causing water to infuse into sells a cell lysis.5 The longer the thawing time, the greater damage to the cells because of increased solute effect and greater recrystallization.5

After freezing, stasis within the vasculature occurs. This loss of circulation and resultant anoxia is a major mechanism of injury from cryosurgery. As the tissue thaws over 0°C (32°F), a brief hyperemic response ensues, with resultant edema and inflammation.

Liquid nitrogen is the cryogen of choice in dermatology. It is easy to store and use, environmentally friendly, nonflammable, inexpensive, and at –195.8°C (–320.4°F), has the lowest temperature of all the common cryogens, causing rapid freeze of treated tissue.

Other available cryogens include fluorinated hydrocarbons, solid carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide (Table 246-1). Fluorinated hydrocarbons are used as topical sprays to provide temporary anesthesia before the removal of skin lesions or the administration of vaccinations. Cryogen spray cooling is also used to reduce the pain of laser surgery and eliminate overheating of the epidermis.6

Patient Selection and Considerations for Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is a destructive modality used to treat benign and malignant skin neoplasms. Several factors, including lesion type, size, depth, border, location, and patient skin type, should be considered when cryosurgery is a treatment choice.

Absolute contraindications to cryosurgery include lesions that require histopathology for diagnosis and recurrent nonmelanoma skin cancers. Relative contraindications to cryosurgery include patients with cold urticaria, abnormal cold intolerance, cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia, or tumors with indistinct borders or darkly pigmented melanotic features.

Risks and Precautions

- Treating lesions overlying nerves, such as the postauricular nerve on the neck or digital nerves on medial and lateral fingers and toes. Damage may result in regional paresthesia or motor dysfunction.

- Treating sites prone to scarring with retraction, such as the eyelids, mucosa, nasal ala, and auditory canal.

- Treating patients with darkly pigmented skin, may result in hypopigmentation at treated sites.

Patient Positioning

Anesthesia

For the majority of patients, anesthesia is not used prior to a cryosurgical procedure. However, cryosurgery is painful, especially in children. 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine may be locally injected prior to treatment. For longer cryosurgery treatment times, such as treatment of skin neoplasms (up to 30 seconds), local anesthesia is mandatory. Topical anesthesia can be applied approximately 1 hour prior to the procedure to minimize pain. A single-center, double blinded, randomized placebo-controlled, parallel-group trail comparing a lidocaine/prilocaine 5% cream applied 1 hour prior to cryosurgery for warts, however, did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in pain during the procedure.7 For longer cryosurgery treatment times, such as treatment for skin neoplasms (up to 30 seconds), 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine can be locally injected prior to treatment.

Techniques for Cryosurgery

Table 246-2 lists targets of cryosurgery with associated cell death temperatures. Melanocytes are the most sensitive to cryosurgery, with cell destruction at –4°C to –7°C (24.8°F–19.4°F).8 Depigmentation may occur, especially in darkly pigmented individuals. Keratinocytes require longer freezing to –20°C to –30°C until cell death and are more resistant to cooling effects. Fibroblasts are the most resistant to freezing and do not undergo cell death until –30°C to –35°C (–22°F to –31°F). A temperature of –50°C to –60°C (–58°F to –76°F) is needed for destruction of malignant lesions, whereas lesser degrees of freezing are needed for benign lesions.

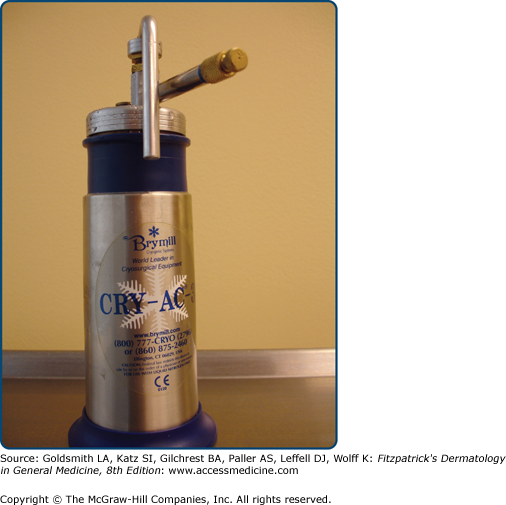

There are several cryosurgical techniques that can be used in treating skin lesions. The open spray method is most frequently used. This method uses a handheld cryosurgical unit with fingertip trigger (eFig. 246-0.1). Spray tips with varying-sized apertures are attached to the unit, emitting a stream of liquid nitrogen toward the lesion from a distance of 1–2 cm. A new model has been released, which measures the temperature on the skin surface.9

Although freeze times vary for lesion types, an intermittent spray in a solid, circular, or paintbrush pattern is normally used. Longer spray times are required for thicker, keratotic lesions or malignant lesions; shorter times are required for thinner, atrophic, or benign lesions. The intermittent spray helps localize treatment to the lesion with a small freeze halo, thus minimizing collateral normal tissue damage. This is particularly important when treating lesions around the orbital, nasal, auricular, genital, or periungual regions.

As the lesion is treated, a lateral freeze spreads beyond the margins of the lesion. The measurement of the surface radius of the freeze is equal to the central depth of the freeze into the skin.5 Temperature gradients exist within the freeze, with colder temperatures in the middle and warmer temperatures toward the periphery. In general, superficial lesions should have a clinical freeze margin of 2–3 mm, and malignant or deeper lesions should have a clinical freeze margin of 5 mm to ensure successful treatment.

The closed technique uses a copper cryoprobe that is attached to the cryosurgical unit. Once the metal probe is pressed against a lesion on the skin, the trigger of the unit is squeezed, and liquid nitrogen leaves the unit through a conduit line that maintains it in a closed system. This technique is useful for treating small, well-circumscribed lesions or lesions found in confined locations.

Similarly, a metal, cone-sized chamber can be attached to the cryosurgical unit and held in contact with the lesion. This allows liquid nitrogen spray to enter the cone and rapidly freeze the lesion. Another cone-apparatus option includes holding an otoscope cover tip against the lesion with one hand while freezing with the cryosurgical unit in the other hand. Treatment times using the cone method should be decreased because the final temperature at the orifice of the cone is obtained faster, when compared with an open spray.

If a cryospray unit is not available, the dipstick technique can be used. First, a small amount of liquid nitrogen is poured into a polystyrene cup or other insulated container. Cotton-tipped swabs are placed tip-down in the container and cooled. Using firm pressure, the cotton-tips are placed against the lesion until a 2- to 3-mm halo forms around the treated lesion. This method is useful where surrounding tissue must be spared, such as periorbital, mucosal, nail, and genital regions.

Alternatively, tissue forceps can be placed in the container and allowed to cool. This method is useful for treating filiform lesions such as verrucae and skin tags. The metal forceps cool rapidly, so gloves should be worn while holding the forceps to prevent freeze injury to the practitioner’s fingers.

Outcomes Assessment for Common Benign Lesions

The spray technique is an effective modality for treating this common lesion. Although longer freeze times of 10–15 seconds with a 1- to 2-mm halo are required for these raised growths, too aggressive freezing may result in scarring or hyperpigmentation. For cosmetic purposes and to prevent pigmentation changes, a lighter freeze followed by curettage may be preferential. Forewarn patients that a second treatment may be required, especially for thicker seborrheic keratoses.

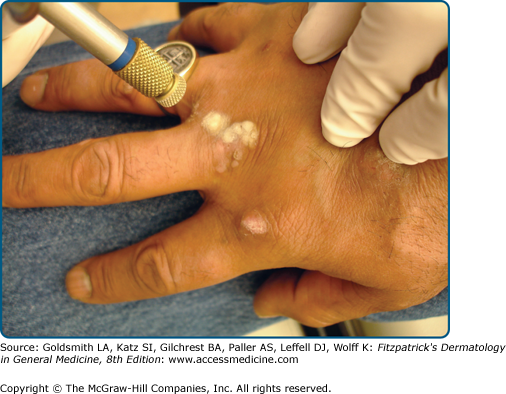

Warts are a common problem, with a high prevalence in the population.10 Although cryosurgery for warts has sustained a common practice in dermatology, varying techniques have been offered with regard to freezing method, number of freeze-thaw cycles, and frequency of treatment sessions. Cryosurgery using the spray technique is probably the most common method due to its quick, convenient use and ease of obtaining a freeze halo around the lesion (Fig. 246-1). The cotton-tip applicator technique is cheaper and may be less frightening to the patient, particularly children. Care must be undertaken not to cross contaminate the liquid nitrogen by reintroducing the cotton-tip applicator into a common flask.

Combination therapy with cryosurgery has also been advocated to treat verrucae. Berth-Jones and Huchinson11 demonstrated a 52% cure rate at 3 months with the combination of cryotherapy, keratolytic wart paint, and paring. The authors also noted that paring the wart before cryotherapy improved the cure rates for plantar warts, but not hand warts.

As shown in Table 246-2, pigmented cells are highly susceptible to freezing. Therefore, these lesions require a shorter freeze time of 3–5 seconds with minimal halo. For darker-skinned individuals, care must be taken not to induce hypopigmentation at treatment sites. Therefore, a test site in a cosmetically less noticeable region may be performed first before treating multiple lesions on sun-exposed areas. In addition, sunscreen with ultraviolet A and ultraviolet protection should be advocated post-treatment.

Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars is frequently unsatisfactory. Cryosurgery is a less common but effective means of treating these recalcitrant lesions. Freeze times of 30 seconds are required over 1-month interval sessions until flattening is achieved. Zouboulis et al reported a prospective study of 93 keloids and hypertrophic scars treated with 30-second freeze times over one to three sessions.12 Improved responses were seen in patients treated with three or more sessions (79%), compared with subjects treated once or twice (33%).

Treatment time may be 60 seconds due to the fibrotic nature of the lesion and the need to treat cells located in the deep dermis. A retrospective study of 393 dermatofibromas treated with cryosurgery reported 65% clearance of a visible and palpable lesion.13

Outcomes Assessment for Premalignant Lesions

Cryosurgery is an effective modality for the treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs). The open spray technique, using a single freeze-thaw cycle of 8–10 seconds, is the treatment of choice (Fig. 246-2). Hypertrophic AKs require longer freeze times while atrophic AKs and AKs on thin-skinned regions require shorter freeze times. A 1- to 2-mm freeze margin around the lesion is adequate. For thicker lesions, pretreatment of emollients or curetting may shorten freezing times.

Although cryosurgery is widely utilized in dermatology for treatment of AKs, there are few well-designed studies assessing cure rates. Lubritz and Smolewski14 treated 1,018 AKs on 70 patients with cryosurgery with 20–45 seconds thaw times. At 1-year post-treatment, they reported a cure rate of 99%.

Another prospective, multicenter study of 421 AKs over 5 mm in diameter on the face and scalp demonstrated a complete response of 39% with a 5-second freeze, 69% for a 5- to 20-second freeze, and 83% for a 20 second freeze.15

Goldberg et al treated a number of AKs with monitoring of the skin surface temperature, and achieved a 100% cure rate after 6 weeks.

In patients with diffuse actinic damage, extensive cryosurgery or cryopeeling, may be useful. Chiarello16 reported cryopeeling was twice as effective as 5-fluorouracil in treating AKs, and preventing squamous cell carcinomas at 1–3 years postoperatively.

Cryosurgery appears useful in well-defined lesions for situations where surgery is less favorable, either for technical or cosmetic reasons, or when the patient prefers this treatment option. The goal of cryosurgery is to cure the patient by destroying the lesion in a single treatment. The margins of destruction of the lesion cannot be assessed using cryosurgery of malignant tumors.