Craniofacial and Maxillofacial Prosthetics

George C. Bohle III

Cherry L. Estilo

Joseph M. Huryn

INTRODUCTION

Prosthetic rehabilitation of the oral cavity and the head and neck is a critical component of rehabilitation following tumor extirpation, trauma, and congenital deformities.1,2 Recent advances in imaging and manufacturing have improved surgical planning by virtual surgery and the availability of custom craniofacial prosthetics. Prosthodontists are important members of the interdisciplinary team who care for the head and neck patients.

Prosthetics for head and neck reconstruction can be categorized based on the anatomic location of the defect. For example, a variety of custom or prefabricated implants and corresponding prostheses are available for acquired defects of the palate, mandible, or external features of the face. When used in this manner, dental and craniofacial implants serve a functional role, aiding in mastication or separating the oral and nasal cavities, or a cosmetic purpose camouflaging scars or improving facial appearance. Custom prostheses can be constructed to replace missing nasal or auricular tissues matching the patients’ skin color and tone. Similarly, prostheses may be used to replace all periorbital tissues after orbital exenteration. Careful analysis of the defect and functional purpose of the prosthesis are integral steps in fabrication.

HARD PALATE DEFECTS

Hard palate defects result from oncologic resection, trauma, or congenital defects. The purpose of prosthodontic rehabilitation is to separate the oral and nasal cavities so that speech and swallowing function are restored. The prosthesis also serves to restore cosmetic appearance by supporting the cheek and lip.

A variety of classification schemes have been proposed by head and neck surgeons, reconstructive surgeons, and prosthodontists for acquired defects of the hard palate based on the individual roles of these groups in the multidisciplinary treatment of head and neck defects3,4,5 (Chapter 39). For example, head and neck or oral surgery classification schemes describe the anatomical structures to be removed and possible approaches for the operation. In contrast, classification systems proposed by plastic and reconstructive surgeons primarily address the missing anatomic structures and algorithms for reconstruction. Lastly, the prosthodontic systems describe the size and location of the defect and the proposed prosthetic rehabilitation for the patient.

Ideally, patients are evaluated by a prosthodontist prior to surgical treatment. Inevitably, however, some patients present after flap reconstruction. In either case, the goal of prosthodontic rehabilitation is a well-fitting, rigidly supported obturator that provides maximum functional and cosmetic outcomes. In many cases, this process involves a series of prostheses designed to allow wound healing and changes in shape and size due to scarring and adjuvant radiation treatment. Most patients have an surgical obturator fabricated prior to surgery and placed in the hard palate defect at the time of the operation. This is followed by an interim obturator when the immediate wound healing issues have been resolved. Finally, patients are fitted with the definitive obturator.

During the preoperative visit, patients are counseled to provide a realistic functional prognosis of the expected outcomes. In addition, a complete intraoral and head and neck examination is performed to evaluate dentition and anticipated prosthetic shape, size, and fixation technique. Impressions of the maxillary and mandibular arches are made at the initial consultation. In general, patients with healthy dentition and smaller defects have better overall comfort and efficacy of the obturator. Obviously, patients who have loss of periodontal support and resultant loose teeth, active caries, fractured teeth, or heavily restored teeth have more difficulties with hard palate prostheses. In some cases, the use of dental implants should be considered for patients missing teeth in the remaining arch in an effort to provide the maximum obturator stability.

Surgical Prosthesis

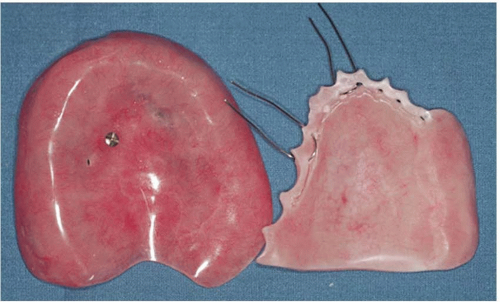

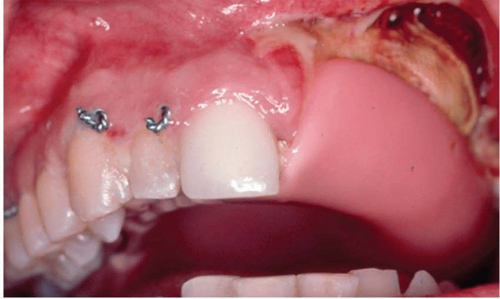

The surgical obturator is fabricated prior to surgery and placed intraoperatively to stabilize packing and provide function upon awaking from the surgery.6 Although the surgical obturator can be retained with wires or screws, wires are usually easier and equally retentive in patients with good dentition (Figure 38.1). Typically, a 24 gauge wire is used in a similar manner as arch bars for intermaxillary fixation (Figure 38.2). Bone wax over the cut wire ends is useful to prevent irritation of the cheek and lip. In some cases, the intramaxillary defect is covered with a split-thickness skin graft by the reconstructive team to accelerate tissue healing and optimize postoperative care.

Prosthetic reconstruction of hard palate defects in edentulous patients is challenging, and patients should be counseled that they might experience difficulty with prosthetic function postoperatively. In these cases, placement of dental implants either at the time of the ablative surgery or after recovery is a good option. All available bone should be used to place as many implants as possible with a minimum of two implants. Placement of mini or conventional dental implants can usually be performed with little extension of the overall operating time by placing the implants while awaiting the pathology results of the frozen sections.7 Upon completion of implant placement, the surgical obturator can be held in place with fixation screws, wires, or sutures as outlined above. Alternatively, a 24 gauge wire can be passed in a transalveolar fashion from lingual to buccal (Figure 38.3).

Interim Prosthesis

Following a brief recovery period, fabrication of the interim obturator is initiated to account for changes in tissue healing and dentition. This obturator is fabricated using a plastic resin and can be shaved/shaped as needed. The original surgical prosthesis is usually removed 5 to 14 days after surgery, the packing is removed, and the interim obturator is adjusted for gross contact and refined for postoperative changes. This process can be repeated and the interim prosthesis further refined as the patient recovers and the wound contracts. Patients are taught how to place and care for their prosthesis and are typically followed every 2 or 3 weeks for fine adjustments as necessary or until wound healing has occurred. Patients undergoing radiation therapy will usually remain in this interim prosthesis for 6 to 12 months, while those not requiring radiation may be healed sufficiently in 3 months to begin the definitive prosthesis.

In edentulous patients who have previously worn maxillary dentures, the interim obturator can be designed using the previous device, which provides several advantages: the patient is accustomed to the feel of the teeth, the occlusion is known, and cosmetic appearance has not been changed. Resilient lining or tissue conditioners are used to add the obturator portion of the prosthesis after adjusting the denture extensions and roughening the surface to allow adhesion of the new material. In addition, retentive elements can be incorporated into the interim obturator giving the prosthesis greater stability by physically connecting to the dental implants.

Definitive Prosthesis

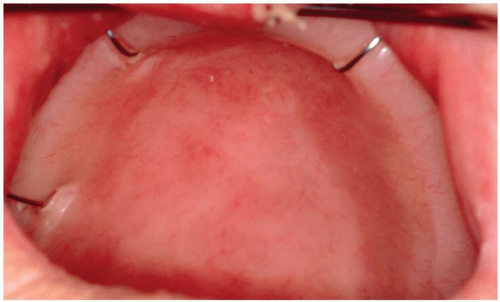

The definitive prosthesis differs from the interim in that it is usually a metallic framework custom cast to fit the remaining teeth and is much stronger than the plastic interim prosthesis. In addition, because healing has nearly completely occurred when the definitive prosthesis is placed, less adjustment is necessary and patients are more accustomed to the feel and routine of wearing a prosthesis. Figure 38.4 demonstrates a well-healed non-reconstructed maxillary defect rehabilitated with dental implants and a definitive obturator. The implants were placed at the time of surgery since the patient had only two remaining teeth to support the obturator.

Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Hard Palate Defects in Patients Reconstructed with Flaps

In some cases, hard palate defects are surgically reconstructed with free flaps (Chapter 39), thereby separating the mouth and nasal cavities with vascularized tissues. These patients are typically referred for prosthetic dental fabrication months after surgery when swelling is decreased and the flap has completely healed. In other circumstances, patients are referred postoperatively after partial or complete flap loss. Failing flap reconstructions may be treated with a prosthesis as an interim measure until the patient can return for additional surgery or as a definitive treatment in conjunction with other measures.

Provided there is physical space available in the oral cavity, a custom prosthesis can usually be fabricated in patients who have undergone flap reconstruction; however, as is the case with all prosthetics, the efficacy of these devices is dependent on the support provided by teeth and dental implants (Figure 38.5). Therefore, bulky flaps that protrude into the oral cavity must, if possible, be reduced in size prior to prosthetic fabrication in order to provide physical space for the prosthesis. Flap reduction is also helpful in stabilizing the prosthetic as the additional weight of a bulky flap usually cannot be overcome with traditional clasps or with implant retentive elements. With a taut flap there is adequate room for the prosthesis, and the patient’s function and cosmesis are greatly improved.

SOFT PALATE DEFECTS

Prosthetic rehabilitation of a soft palate defect is one of the most challenging intraoral treatments a maxillofacial prosthodontist will render. Surgical, traumatic, or developmental alterations of the soft palate alter normal palatopharyngeal closure, resulting in hypernasal speech and food bolus/liquid regurgitation. This muscular sphincter is made of the posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls that move anteriorly and medially to meet the superiorly elevated soft palate to close the oropharynx from the nasopharynx. A speech aid obturator prosthesis allows palatopharyngeal closure in these patients by allowing the lateral and posterior walls of the nasopharynx to contract against the prosthesis. The obturator must therefore be sized precisely to allow unimpeded nasal breathing and should not interfere with the tongue during swallowing and speech.

Velopharyngeal inadequacy (VPI) is the inability of the sphincter to separate the nasopharynx from the oral pharynx. VPI can be caused by one or a combination of the following conditions. Velopharyngeal insufficiency results from loss of anatomic structure from the sphincter.

The remaining musculature continues to form some part of the sphincter but there is a physical defect present. This condition is treated by surgery or fabrication of a soft palate obturator. Velopharyngeal incompetency results from an anatomically intact sphincter with muscle incompetency due to disruption of nerve innervation or damage secondary to radiation therapy. All of the muscles of the sphincter are present in complete form but one or more do not function adequately to form the seal, resulting in hypernasal speech and regurgitation of food and fluids through the nose upon swallowing. This condition can be treated with surgery or with the fabrication of a palatal lift prosthesis. By lifting and holding the anatomically intact soft palate in place, the sphincter is restored and speech and swallowing improved.

The remaining musculature continues to form some part of the sphincter but there is a physical defect present. This condition is treated by surgery or fabrication of a soft palate obturator. Velopharyngeal incompetency results from an anatomically intact sphincter with muscle incompetency due to disruption of nerve innervation or damage secondary to radiation therapy. All of the muscles of the sphincter are present in complete form but one or more do not function adequately to form the seal, resulting in hypernasal speech and regurgitation of food and fluids through the nose upon swallowing. This condition can be treated with surgery or with the fabrication of a palatal lift prosthesis. By lifting and holding the anatomically intact soft palate in place, the sphincter is restored and speech and swallowing improved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree