Cosmetic Aspects of Common Benign Tumors

Doris M. Hexsel

Mariana Soirefmann

Benign tumors are frequent in all skin types. The diagnosis of benign skin tumors may need careful dermatologic exam; patient history and familial history; physical exam, including gross visualization; dermoscopy; and biopsy to confirm it is truly benign and to rule out malignancies.

Benign tumors are mainly located on the face, interfering with the appearance not only by fact of the lesions themselves but also because some are numerous.

All benign skin tumors may affect darker racial ethnic groups, but some are more frequent. This chapter will discuss the diagnosis and treatment of the most frequently benign skin tumors, including dermatosis papulosa nigra, dermatofibromas, acrochordons (skin tags), syringomas, trichoepitheliomas, and sebaceous hyperplasia.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

General features

Dermatosis papulosa nigra (DPN) is a pigmented eruption of the face and neck caused by a nevoid development defect of the pilosebaceous follicles, with histology resembling seborrhoeic keratosis.1,2 The condition occurs almost exclusively in darker racial ethnic groups and is more frequent in women than in men.3,4

DPN is probably genetically determined.1 It begins to appear in adolescence or early adulthood and progresses with age.3,5 Incidence in darker racial ethnic groups rises from about 5% in the first decade to more than 40% by the third decade.1 It has been estimated that lesions of DPN occur in about 50% of dark-skinned patients.3 Dunwell and Rose studied 1,000 Afro-Caribbean patients and found DPN a notable common diagnoses.6 Babapour et al. reported a case of DPN in a 3-year-old dark-skinned boy.7 Grimes et al. studied 82 dark-skinned patients and reported predominance in women of almost 2:1. Fifty-four percent of these patients reported that other members of their families were also affected.8 Some authors believe DPN to be a variant of seborrheic keratosis, whereas others consider both lesions as variants of epidermal nevus with delayed onset. A few regard DPN as a variant of acrochordon.3

Individual lesions are black or dark brown, flattened or cupuliform papules 1 to 5 mm in diameter1,3 and can be elevated from 1 to 3 mm above the skin.4 Older lesions can become very long and pedunculated or filiform. Growth rate and size usually slow during the fifth or sixth decade.4 They are more common on the face and neck, especially on the upper cheek area, although they may form on almost any area of the body. Any one individual can have hundreds, even thousands, of these lesions.1,4 DPNs are benign epidermal tumors that do not spontaneously regress.3 There have been no reports of malignant degeneration, and the lesions are not associated with any systemic diseases or syndromes.3,4 They are usually free of pain and itching, although these can develop if the lesions become large and are irritated by friction from clothing. Although lesions may hang over the eyelids and obstruct vision, most patients are more concerned with the cosmetic effects of the lesions than with health effects.4 The epidermis occasionally has a gently lobulated configuration, similar to that seen in a fibroepithelial polyp. The keratinocytes are basaloid, and horned pseudocysts may be present, resembling seborrheic keratosis.3

The clinical differential diagnosis of DPN is relatively small, as these lesions have a classic appearance. Lesions that might be considered in the differential diagnosis include multiple seborrheic keratoses or verrucae, fibroepithelial polyps, syringomas, and trichoepitheliomas. Multiple pigmented melanocytic nevi might rarely be mistaken for DPN.3

Treatment

DPNs can cause significant cosmetic and functional impairment when they occur in a frequent location, such as head and neck area. Multiple methods of treatment—including surgery, cryosurgery, curettage, and superficial chemical peeling—have been reported in the literature (Table 35-1).3 However, it is important to inform the patient that any treatment is likely to cause more cosmetic disturbance than the lesions themselves.5

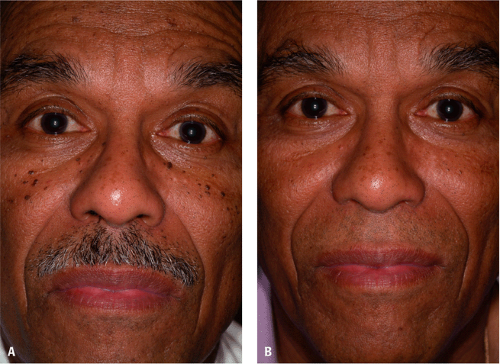

Figure 35-1 A: Dermatosis papulosa nigra: baseline. B: Dermatosis papulosa nigra after epilation of multiple lesions. (Courtesy of Pearl E. Grimes, MD.) |

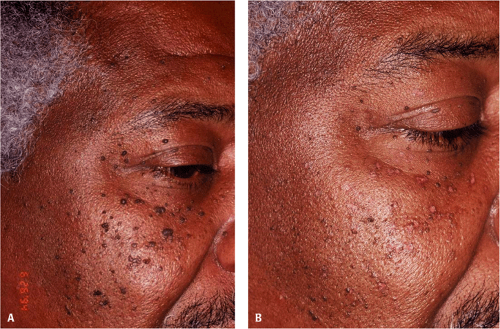

Treatment is usually surgical. Electrodesiccation and curettage is a common and accepted technique for removing DPN lesions5 (Fig. 35-1A,B and Fig. 35-2A,B). Electrodesiccation is also routinely performed for destruction of benign skin lesions, including DPN.9 Results are normally successful when the procedure is done by an experienced practitioner and follow-up care is given.4 Kauh et al. reported success on the use of curettage with a small, sharp curette without anesthesia. There was little bleeding and no postoperative scarring or significant pigmentary change in several hundred patients, mostly African Americans, who were followed for 10 years.10 Moreover, electrofulguration is ideal for very superficial benign lesions, such as DPN. This procedure carbonizes the surface of the lesion, protecting deeper tissue from additional fulguration, so healing is rapid and scarring rare.11 Chemical peeling using alpha hydroxyl acids will soften and flatten these lesions and does seem to prevent some new lesions. Daily use of lactic acid or other alpha hydroxyl acid–containing lotion or creams is also useful.3 Cryosurgery results in variable pigmentation and is not considered the treatment of choice for DPN.3

Complications

Some degree of hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation can be expected from surgical procedures. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may occur in dark-skinned patients, and it is more frequent than hypopigmentation changes in such patients. Cryosurgery should be undertaken with caution because of the potential for hypopigmentation in black skin,4 as the melanocytes are very sensitive to this surgical treatment modality. Electrodesiccation is successful, but may also result in hyperpigmentation.3

Dermatofibromas

General features

Dermatofibroma (DF) (also called benign fibrous histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma, or histiocytoma cutis) is a benign dermal and often superficial subcutaneous proliferation of oval cells resembling histiocytes and spindle-shaped cells resembling fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.12 The etiology of DF is unknown, but recent cytogenetic studies demonstrating clonality favor these lesions being neoplastic.12 The previous theory that DF is a dermal response to injury, such as an insect bite, trauma, or vaccination, has been challenged.12 DF is the most frequent fibrohistiocytic skin tumor. Occurrence is more frequent in women than men, and it appears most often in middle age.13 Child et al., in a study of prevalence of skin disease in a dark-skinned population in southeast London, showed that dermatofibroma is sufficiently common in this population. It was the ninth (2.7%) dermatological diagnostic

most common in 274 consecutive dark-skinned patients.14 Another more recent article that revised the more common cutaneous alterations of ethnic skin did not cite dermatofibroma as a frequent dermatosis in darker racial ethnic groups, neither in Asian or Hispanic racial groups.15

most common in 274 consecutive dark-skinned patients.14 Another more recent article that revised the more common cutaneous alterations of ethnic skin did not cite dermatofibroma as a frequent dermatosis in darker racial ethnic groups, neither in Asian or Hispanic racial groups.15

Figure 35-2 A: Dematosis papulosa nigra: baseline. B: Dermatosis papulosa nigra after epilation and iris scissor excision of multiple facial lesions. (Courtesy of Pearl E. Grimes, MD.) |

DFs usually appear in adults as a single or multiple firm pigmented papules or nodules that grow slowly and can develop anywhere in the body surface, with predilection for the lower limbs. Their size ranges from a few millimeters to 2 cm, and their color varies from light brown to dark brown, yellow-red, brown-red, or black. They are commonly asymptomatic and rarely can be associated with mild symptoms on palpation. Lateral compression frequently causes dimpling of the skin (Fitzpatrick’s sign), although it is not pathognomic.16 A number of clinicopathological variants of DF have been described. Cellular DFs are larger lesions, more commonly found in men and on the limbs, and represent less than 5% of all DFs. Aneurismal DFs are rapidly growing lesions that mimic a vascular tumor. Atypical DFs are more common in young men, with a predilection for lower limbs. Epithelioid DFs resembles a nonulcerated pyogenic granuloma and present on the lower limbs of young women.12 Atrophic DF occurs more in women, on the upper trunk, and represent approximately 2% of all DFs.17 Occasionally, DF is associated with immature follicular structures, which may be confused with basal cell carcinoma.18

Dermoscopy can assist in the recognition of DF, mainly to differentiate the DF diagnosis with the diagnosis of melanocytic diseases. There seem to be three standards of DF: (a) isolated pigment network, (b) peripheral pigment network with dark brown globules and dots or with scale crust in the central area, and (c) peripheral pigment network with a central white area.16

Treatment

DFs can be treated with surgical excision, cryosurgery, and intralesional injection of corticoid with variable results. All these therapeutic modalities are related with scars and dyschromias, which are more evident in dark-skinned patients. Wang and Lee reported that pulsed-dye laser is a safe and effective treatment of these lesions.19

Complications

Cellular, aneurysmal, and atypical variants should be completely removed because of the risk of local recurrence and distant metastases.12

Acrochordons (Skin Tags)

General features

Acrochordons or skin tags (ST) (also called soft warts) are a common benign, cosmetically disfiguring lesion composed

of loose fibrous tissue and occurring mainly on the neck and major flexures as a small soft pedunculated protrusion. They are frequently found together with seborrhoeic keratoses.1 These lesions are very common, particularly in women at the menopause or later.1 They are derived from ectoderm and mesoderm and represent a hyperplastic epidermis.20 STs are found in 25% of all people and increase in number with age.20 Obesity is a predisposing factor.18,20 Multiple lesions may appear in the latter trimesters of pregnancy, and as they often resolve postdelivery, it has been suggested that they are probably due to hormonal factors.21 Multiple acrochordons can be found as part of syndromes, such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome22 (fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons) and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome23

of loose fibrous tissue and occurring mainly on the neck and major flexures as a small soft pedunculated protrusion. They are frequently found together with seborrhoeic keratoses.1 These lesions are very common, particularly in women at the menopause or later.1 They are derived from ectoderm and mesoderm and represent a hyperplastic epidermis.20 STs are found in 25% of all people and increase in number with age.20 Obesity is a predisposing factor.18,20 Multiple lesions may appear in the latter trimesters of pregnancy, and as they often resolve postdelivery, it has been suggested that they are probably due to hormonal factors.21 Multiple acrochordons can be found as part of syndromes, such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome22 (fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons) and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree