Correction of Ptosis in the Previously Augmented Breast

Neal Handel

Managing ptosis in the previously augmented patient is an important topic that has not received the attention it deserves. Most women initially undergo breast augmentation in their 20s or early 30s (1). Over time, predictable changes occur in the augmented breast that often lead patients to return for additional surgery (2). Some of these changes are consequences of normal physiologic and aging processes. For example, the breast undergoes involution accompanied by loss of volume, fatty replacement, stretching of skin, diminished elasticity, and progressive ptosis. Pregnancy, breast-feeding, and fluctuations in weight may accelerate these processes. Changes also occur as a direct consequence of the implant, including compression atrophy and thinning of soft tissues, additional skin stretching, acceleration of ptosis, and frequently the development of capsular contracture.

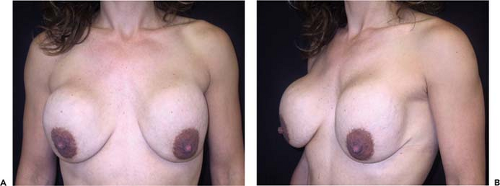

Many augmented patients present requesting correction of ptosis that has occurred gradually over time. These women generally have a similar constellation of findings, including moderate to severe stretching of the skin envelope, atrophy and thinning of the breast tissue, and some degree of contracture (Fig. 132.1) They desire improvement in breast shape and restoration of softness, but few are willing to accept a decrease in breast size. In fact, many patients undergoing secondary surgery want larger implants. The majority of such patients undergo some combination of capsule surgery, mastopexy, and implant exchange. These patients are challenging because consistently good aesthetic results are difficult to achieve, complications are relatively frequent, and disasters occasionally occur.

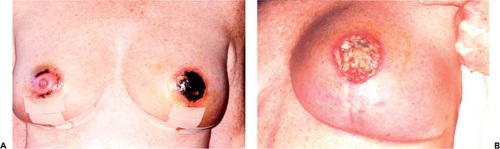

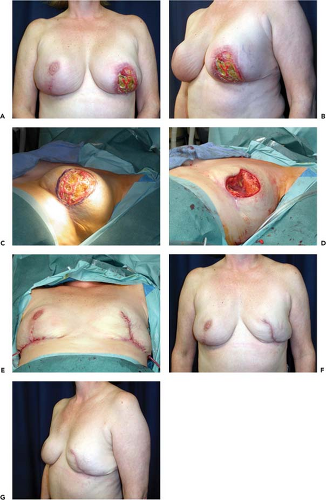

My interest in this subject was stimulated after observing a high rate of complications and unsatisfactory outcomes in augmented patients undergoing delayed mastopexy. Some were my patients who suffered wound-healing delays, unsatisfactory nipple position, and suboptimal scarring. I have also seen many patients who were referred with severe complications, including extensive skin necrosis, fat necrosis, infections, implant exposure, and partial or full-thickness loss of the nipple and areola (Figs. 132.2 to 132.5).

When these secondary cases result in poor outcomes, it is not only disappointing to the patient, but also worrisome and stressful to the surgeon as well. Such adverse outcomes can also be costly for malpractice carriers. In recent years, litigation stemming from secondary implant surgery has resulted in the greatest monetary losses arising from plastic surgery cases. If patients experience extensive scarring, nipple-areolar loss, or permanent disfigurement of the breast, judgments or settlements are typically in the range of $250,000 to $800,000 (M. Gorney, The Doctors Company, Napa, CA, personal communication, 2003).

There are several reasons why the combination of capsule surgery, mastopexy, and implant exchange is a high-risk procedure. Some of the increased risk arises simply from performing multiple breast procedures simultaneously. For example, it has been reported that when augmentation and mastopexy are combined, the increase in risk is more than just additive. Breast augmentation alone has a relatively low risk of complications, and they are usually not severe. Likewise, when mastopexy alone is performed, the complication rate is relatively low, and the problems quite manageable. However, as Spear (3,4) observed, when the two operations are combined into a single procedure, each operation makes the other more difficult, and each increases the likelihood of complications arising from the other. This occurs because the operations have conflicting goals. The aim of mastopexy is to elevate the nipple and tighten the breast, which is accomplished by reducing the skin envelope. The objective of augmentation is to increase breast volume, which is accomplished by expanding the skin envelope. Thus, concomitant mastopexy and augmentation may result in a relative insufficiency of soft tissue to accommodate the implant, resulting in increased wound tension and devascularization of tissues. The risk of nipple loss is much greater with combined augmentation and mastopexy than with augmentation alone or mastopexy alone (Figs. 132.6 and 132.7). Other adverse consequences arising from combined augmentation-mastopexy include an increased risk of flap necrosis with wound dehiscence and implant exposure, wide or unattractive scars, excessively dilated areolas, unsatisfactory nipple position, diminished skin sensation, fat necrosis, and infection.

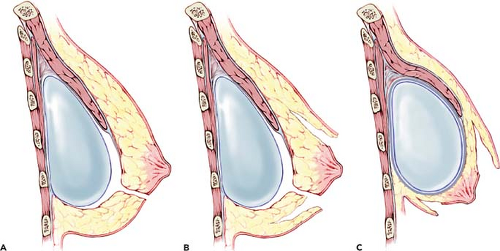

When performing surgery to correct ptosis in previously augmented patients, one must contend not only with the increased surgical risk attendant to combined procedures, but also with the significant physiologic and anatomic changes of the breast caused by implants. The most important adverse effect of implants is the thinning and atrophy of breast tissue that inevitably occurs over time.

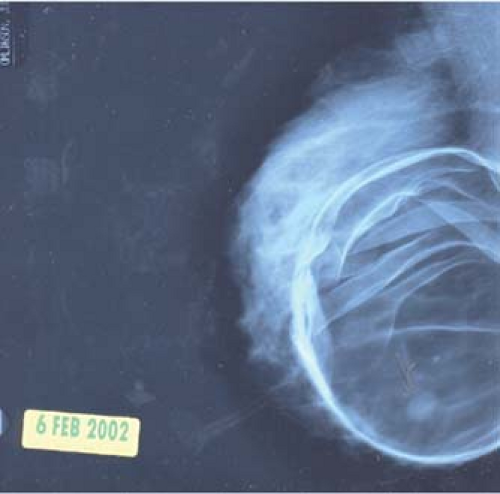

Plastic surgeons have long been aware that tissue atrophy occurs adjacent to implanted prosthetic devices. In fact, even relatively rigid, nonmalleable tissues are affected; many patients with silicone chin implants have some atrophy of the adjacent mandible (5,6), and erosion and depression of the bony thorax has been described secondary to breast implants. If rigid tissues like bone and cartilage undergo atrophy from implants, it is likely that such changes would be even more dramatic in soft tissues such as the breast. Indeed, it is commonly observed that the soft-tissue envelope surrounding a breast implant becomes extremely attenuated in augmented patients. This finding was emphasized by Tebbetts (7), who observed that the “consequences of excessively large breast implants include ptosis, tissue stretching, tissue thinning, inadequate soft-tissue cover [and] subcutaneous tissue atrophy.” As a result of gravity, most of the thinning and tissue atrophy occurs along the inferior pole of the breast. This can be demonstrated on physical examination (Fig. 132.8), and is confirmed on mammograms of the augmented breast (Fig. 132.9).

Figure 132.2. A 49-year-old woman sustained complete loss of right nipple-areolar complex after explantation, capsulectomy, mastopexy (Wise skin pattern), and insertion of new implants. |

Figure 132.3. A 26-year-old woman with full-thickness loss of nipple-areolar complex and central fat necrosis of the breast after capsulotomy, implant exchange, and periareolar mastopexy. |

Patients with implants present for prolonged periods not only have tissue thinning and stretching, but also are likely to have a history of previous operations for capsular contracture (8). The surgery performed to relieve contracture, either capsulotomy or capsulectomy, further thins residual breast tissue and compromises blood supply. In addition, with the exception of those who had a transaxillary or transumbilical approach, augmented patients have scars on their breasts from the original procedure; these scars may further impair blood supply to the skin of the breast or nipple-areolar complex.

There is a continuum of risk associated with cosmetic breast operations. The safest operations are primary augmentation alone or primary mastopexy alone. Intermediate in terms of risk is combined augmentation and mastopexy. The highest risk occurs in augmented patients with contracture and ptosis undergoing simultaneous implant exchange, capsule surgery, and mastopexy. The anatomic features of these various groups and their impact on the risk of surgical complications are illustrated in Figure 132.10.

Figure 132.9. Compression mammogram of an augmented breast reveals thick breast parenchyma superiorly but thinned, atrophic tissue inferiorly. |

There is a range of treatment options available for augmented patients who have ptosis, with or without contracture. The first is explantation alone, without mastopexy or implant replacement. The second is capsule surgery only, including repositioning of the prosthesis but without mastopexy. A third option is mastopexy alone, without manipulation of the implant. A fourth possibility is explantation with mastopexy. The final option (the riskiest and most frequently performed) is simultaneous explantation, capsule surgery, mastopexy, and insertion of an implant.

Patients who fall into the first category—explantation without mastopexy or reinsertion of an implant—are among the least frequently encountered. However, some individuals with only moderate ptosis and good skin elasticity achieve surprisingly good results simply from explantation. If the surgeon is unsure about how well the skin envelope will contract, mastopexy can always be delayed until a secondary procedure. When performing explantation without immediate reinsertion of an implant, it is advisable to perform a thorough capsulectomy. Usually in patients with a submammary prosthesis, total capsulectomy can be accomplished easily. In those with subpectoral implants, the anterior capsule adjacent to the breast parenchyma can be resected, but excising capsule from the undersurface of the pectoral muscle is tedious and often bloody. One alternative is to score or roughen the capsule with cautery. Likewise, if the posterior capsule is densely adherent to the underlying ribs and intercostal fascia, there is a risk of excessive bleeding and even of a parietal pneumothorax in attempting to resect it. In such cases, roughening of the posterior capsule, either with mechanical abrasion or cautery, will create a raw surface to assure tissue adhesion after the implant is removed. Suction drains in the early postoperative period are mandatory.

When substantial portions of the capsule are left in situ, they tend to persist indefinitely. This may contribute to seroma formation and will certainly impair reattachment of the breast to the underlying chest wall. For these reasons, capsulectomy to the greatest degree practical is recommended.

When substantial portions of the capsule are left in situ, they tend to persist indefinitely. This may contribute to seroma formation and will certainly impair reattachment of the breast to the underlying chest wall. For these reasons, capsulectomy to the greatest degree practical is recommended.

A second and more common category of patients is made up of women who present with “pseudo-ptosis” of the nipple. In these individuals, there often is capsular contracture with superior displacement of the implant. When this occurs in conjunction with laxity of the overlying skin envelope, the nipple-areolar complex can “hang over” the breast mound, pointing downward, giving the appearance of nipple ptosis. In most of these cases the nipple is not actually beneath the inframammary crease, and the appearance of “ptosis” arises as a result of superior malposition of the implant. Often, excellent correction can be achieved with capsulotomy or capsulectomy and modification of the pocket to lower the fold (Fig. 132.11). Sometimes insertion of a larger prosthesis will also help to fill out the redundant skin envelope. If the patient has adequate soft tissue coverage to camouflage the implant, conversion from the submuscular to the submammary or dual-plane position will also often enhance the result by allowing the soft issue to redrape over the implant in a more aesthetically pleasing fashion.

Occasionally one encounters patients who require only mastopexy to achieve the desired improvement. If a patient does not have contracture and the implant is in good condition and in satisfactory position, mastopexy alone is indicated. This circumstance arises frequently in mastectomy patients who were reconstructed with an implant and had contralateral augmentation for symmetry. The augmented breast is much more likely to become ptotic over time than the reconstructed breast, and “touch-up” mastopexy is often necessary to maintain symmetry (Fig. 132.12). The important technical point to bear in mind is that the breast tissue is attenuated, and therefore dissection of the mastopexy flaps must be done in a plane that preserves skin blood supply yet does not interfere with the vascular pedicle to the nipple.

The next option available for augmented patients with ptosis is explantation with mastopexy, without reinsertion of a new prosthesis. This choice appeals to many women, particularly those who have had implants for a long time and no longer wish to be as full breasted, or women who have undergone multiple prior implant operations and wish to eliminate the risk of future implant-related problems (Fig. 132.13). There are also some individuals in whom performing explantation and mastopexy is a useful first stage, with the intention of going back later to insert a new pair of implants. This certainly decreases risk compared to combining all of the procedures into a single operation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree