Correction of Le Fort I Fracture

Ananth S. Murthy

DEFINITION

The maxilla forms most of the middle third of the facial skeleton. It is attached to the zygomatic bone and nasoethmoid area.

There are a series of vertical and horizontal buttresses to absorb energy during impact by alternating thick and thin structures of the bones.

Le Fort I fractures occur above the apices of the dental roots, continue across the base of the maxillary sinus, and extend to the pterygoid process.

ANATOMY

The maxilla forms portions of the orbit, nasal cavity, and oral cavity.

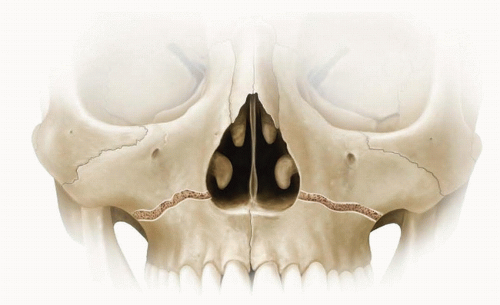

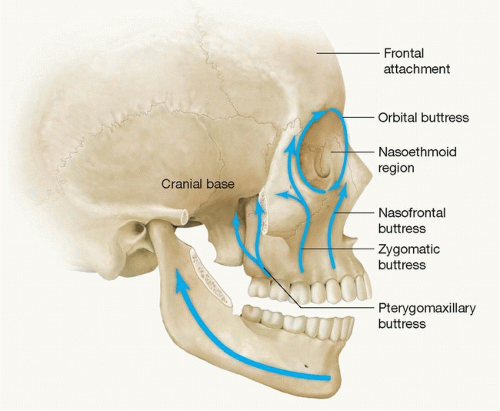

It contributes to the stability of the face by interacting with the cranium to form buttresses (FIG 1).

Nasofrontal buttress: Medially with nasal bones and glabella (frontal bone)

Zygomatic buttress: Laterally with the zygoma, which further articulates with the frontal bone, sphenoid, and temporal bone

Pterygomaxillary buttress: Posteriorly with sphenoid

Four processes: Frontal, zygomatic, palatine, and alveolar

During childhood, the maxilla acts as a tooth bank. As permanent teeth erupt and sinuses form, the anterior wall becomes thin and the alveolar segment becomes thick. With aging, as permanent teeth exfoliate, the alveolar segment resorbs and recedes.

FIG 1 • A series of vertical and horizontal buttresses (alternating thick and thin structures of the bones) that absorb energy during impact.

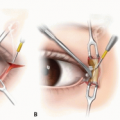

The infraorbital nerve passes through the infraorbital canal in the anterior maxilla and supplies sensation to the upper lip and lateral portion of the nose.

Fractures of the maxilla are caused by direct impact; pattern and distribution vary depending on magnitude and direction of force.

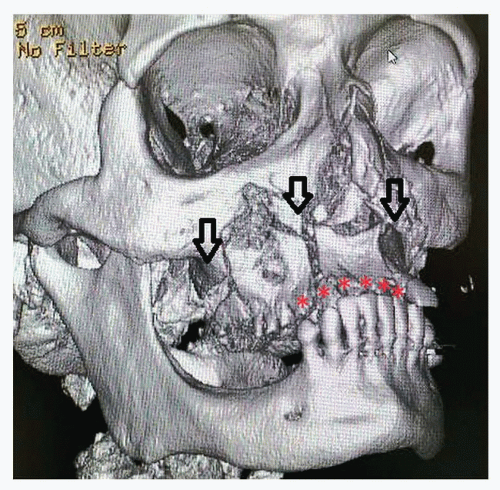

Le Fort I fractures usually occur in combination with other maxillary and/or facial fractures (FIG 2).

PATHOGENESIS

The most common cause is a frontal impact.

The victim is usually thrown forward, striking the midface against an object, for example, the dashboard or steering wheel of a car.

Displacement of the maxilla is generally posterior and inferior. Pterygoid musculature aids in this direction of displacement.

Because of this displacement, premature contact of molars often results in an anterior open bite.

Untreated fractures will result in maxillary retrusion and decreased facial height and malocclusion.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Mobility of maxillary dentition is the hallmark of a maxillary fracture.

Force applied by grasping the anterior portion of the maxilla with the thumb and index finger elicits mobility of the maxilla. Integrity of the palate should be assessed in cases of segmental or split palatal fractures.

Epistaxis, ecchymosis, and edema are seen.

There is midface retrusion, and malocclusion is present.

There may be hematoma and lacerations of the buccal mucosa.

Evaluation for other fractures of the face, especially nasal fractures, should be performed, as isolated fractures of the maxilla are rare.

IMAGING

Computed tomography (CT) scan is required for diagnostic examination of the maxilla. Axial cuts are best to demonstrate fractures of the maxilla.

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions aid in assessing symmetry and displacement of the maxilla (FIG 3).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Timing of surgery depends on the severity of injury.

Open, unstable fractures with hemorrhage will need emergent care.

Closed fractures with displacement and malocclusion should be treated within a week of injury.

Initial treatment should be directed toward airway control, hemostasis, and maxillomandibular fixation.

When comminuted fractures are present along with oronasal hemorrhage, and unstable midface, then, tracheostomy should be performed to obtain airway control.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree