Corns and Calluses: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Every human being, with the exception of the nonweight-bearing infant, is vulnerable to the development of corns and calluses, because the skin is subjected to regular mechanical stress. The prevalence of corns and calluses can be readily appreciated by the number of nonprescription products aimed at reducing or preventing them—a billion-dollar market annually.

The earliest known discussion of these lesions can be found in the writings of Cleopatra, who authored a textbook on cosmetics.1 Corns and calluses have plagued humankind since antiquity, affecting those at all socioeconomic levels.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Corns and calluses result from the prolonged application of excessive mechanical shear or friction forces to the skin. In theory, these forces induce hyperkeratinization, which leads to a thickening of the stratum corneum, although the precise mechanism by which this occurs remains unknown. If the abnormal forces are distributed over a broad area (i.e., more than 1 cm2), a callus develops. In contrast, a corn will form if the same forces are applied to a focused location, with the lamellae of the stratum corneum becoming impacted to form a hard central core known as the radix or nucleus (Fig. 98-1).

Mechanical keratoses are not determined genetically. Heredity does play a role, however, in configuring the individual’s skeletal architecture. A family history of bony abnormality or ligamentous laxity predisposes the person to the presence of sites of increased cutaneous friction or shear. The prevalence of these lesions has also proven to be significantly higher in females, certain ethnic groups, and mentally ill patients.2,3

Clinical Findings

Corns and calluses produce painful symptoms often described as burning, especially when the affected area is weight bearing and/or shoes are worn. This discomfort is thought to result from microtearing of the thickened, inflexible skin.

Corns [clavi or helomata (singular: clavus or heloma)] and calluses [tylomata (singular: tyloma)] are, respectively, keratotic papules and plaques that occur in areas that are subject to sustained excessive mechanical shear or friction forces.

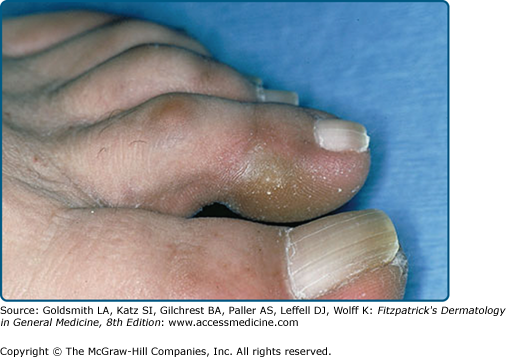

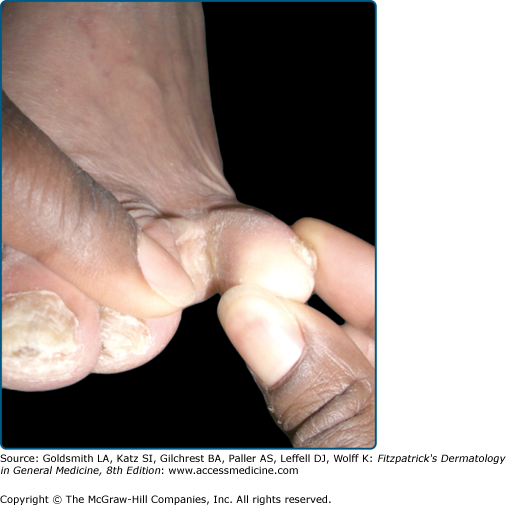

The lesions occur in predictable pedal locations, corresponding to a structural deformity or biomechanical fault. Crookedness of the lesser toes leads to prominence of the proximal and/or distal interphalangeal joints. Keratoses can therefore form either dorsal to those joints, between the toes, at the distal end of the toe, or on the lateral aspect of the fifth toe and/or toenail (lateral toenail corn, also known as Durlacher’s corn; see eFig. 98-1.1). Interdigital corns can be hard when they are adjacent to the interphalangeal joint(s) (see eFig. 98-1.2) or soft when deep within the fourth interdigital space. The softness of latter last corn results from trapped perspiration, which leads to maceration of the keratotic tissue (Fig. 98-2).

In patients with bunions (hallux valgus), a callus usually forms at the medioplantar aspect of the hallux. During gait, the individual rolls off that portion of the great toe because of its incorrect position. The skin is subsequently pinched to form a “pinch callus” (see eFig. 98-2.1). In addition, the first metatarsal often does not bear its fair share of the weight-bearing load. Weight is therefore transferred laterally to the second metatarsal head, which usually leads to the development of an additional corn or callus beneath that bone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree