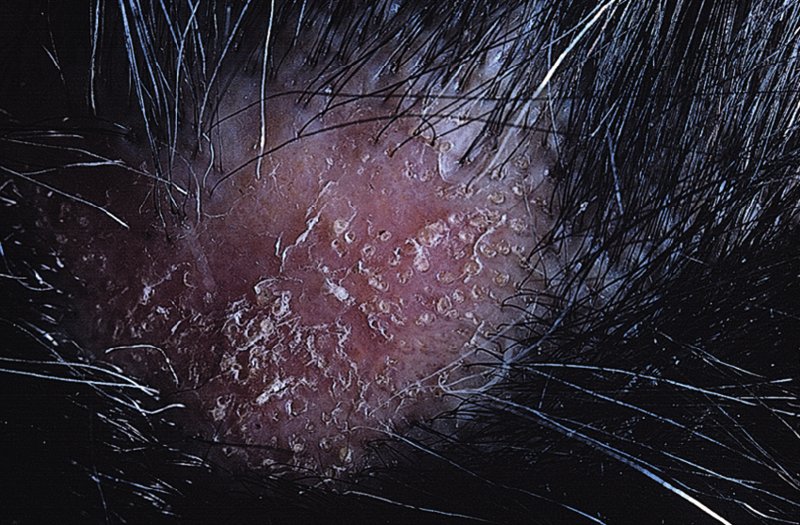

10 The cardinal feature of these conditions is inflammation in the connective tissues which leads to dermal atrophy or sclerosis, to arthritis, and sometimes to abnormalities in other organs. In addition, antibodies form against normal tissues and cellular components; these disorders are therefore classed as autoimmune. Many have difficulty in remembering which antibody features in which condition; Table 10.1 should help here. Table 10.1 Some important associations with non-organ-specific antibodies. The main connective tissue disorders present as a spectrum ranging from the benign cutaneous variants to severe multisystem diseases (Table 10.2). Table 10.2 Classification of connective tissue disease. Lupus erythematosus (LE) is a good example of such a spectrum, ranging from the purely cutaneous type (discoid LE), through patterns associated with some internal problems (and subacute cutaneous LE), to a severe multisystem disease (systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE; Table 10.2). It is characterized by loss of tolerance to nuclear self antigens, with the subsequent development of pathogenic autoantibodies which damage the skin an other organs. Variations in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are the most important genetic risk factor for the development of SLE, and a number of non-MHC genetic variants also play a part. Exposure to sunlight and artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVR) may precipitate the disease or lead to flare ups, probably by exposing previously hidden nuclear or cytoplasmic antigens to which autoantibodies are formed. Such autoantibodies to DNA, nuclear proteins and other normal antigens are typical of LE, and immune complexes formed from these are deposited in the tissues or found in the serum. Hydralazine and procainamide are the most likely drugs to trigger SLE, while isoniazid, methyldopa, quinidine, minocycline, chlorpromazine and anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents precipitate the disease just occasionally. Typically, but not always, the onset is acute. SLE is an uncommon disorder, affecting women more often than men (in a ratio of about 8 : 1). The classic rash of acute SLE is an erythema of the cheeks and nose in the rough shape of a butterfly (Figures 10.1 and 10.2), with facial swelling. Blisters occur rarely, and when they do they signify very active systemic disease. Some patients develop widespread discoid or annular papulosquamous plaques very like those of discoid LE; others, about 20% of patients, have no skin disease at any stage. Figure 10.1 In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (left) the eruption is often just an erythema, sometimes transient, but occupying most of the ‘butterfly’ area with sparing of the nasolabial fold. In discoid LE (right) the fixed scaling and scarring plaques may occur in the butterfly area (dotted line), but can occur outside it too. Figure 10.2 Erythema in the butterfly area, suggestive of SLE. Other dermatological features include peri-ungual telangiectasia (see Figure 10.7), erythema over the digits, hair fall (especially at the frontal margin of the scalp) and photosensitivity. Ulcers may occur on the palate, tongue or buccal mucosa. The skin changes may be transient, continuous or recurrent; they correlate well with the activity of the systemic disease. Acute SLE may be associated with fever, arthritis, nephritis, polyarteritis, pleurisy, pneumonitis, pericarditis, myocarditis and involvement of the central nervous system. Internal involvement can be fatal, but about three-quarters of patients survive for 15 years. Renal involvement suggests a poorer prognosis. The skin disease may cause scarring or hyperpigmentation, but the main dangers lie with damage to other organs and the side effects of treatment, especially systemic steroids. SLE is a great imitator. Its malar rash can be confused with sunburn, polymorphic light eruption (p. 263) and rosacea (p. 164), but is more livid in colour and swollen in texture. The discoid lesions are distinctive, but are also seen in discoid LE and in subacute cutaneous LE. Occasionally, they look like psoriasis or lichen planus (p. 69). The hair fall suggests telogen effluvium (p. 178). Plaques on the scalp may cause a scarring alopecia. SLE should be suspected when a characteristic rash is combined with fever, malaise and internal disease (Table 10.3). Table 10.3 Criteria for the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (must have at least four). Conduct a full physical examination, looking for internal disease. Biopsy of skin lesions is worthwhile because the pathology and immunopathology are distinctive. There is usually some thinning of the epidermis, liquefaction degeneration of epidermal basal cells and a mild perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence is helpful: immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, IgA and C3 are found individually or together in a band-like or granular pattern at the dermo-epidermal junction of involved skin and often uninvolved skin as well. Relevant laboratory tests are listed in Table 10.4. Table 10.4 Investigations in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). ENA, extractable nuclear antigens; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Ig, immunoglobulin; LE, lupus erythematosus. Systemic steroids are helpful in gaining control of acute exacerbations, but should not be used for routine use because of the risk of adverse effects. Large doses of prednisolone (Formulary 2, p. 419) are often needed to achieve control, as assessed by symptoms, signs, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), total complement level and tests of organ function. Having gained control with systemic steroids,slower acting immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate, azathioprine (Formulary 2, p. 418), cyclophosphamide and other support drugs (e.g. antihypertensive therapy or anticonvulsants) can be introduced. Antimalarial drugs may help some patients with marked photosensitivity, but the effectiveness of these is reduced in smokers. Sunscreen and appropriate clothing should reduce UV-induced flares. Long-term and regular follow up is necessary and the disease should be managed in conjunction with a rheumatologist. This is less severe than acute SLE. Sometimes only the skin is affected but about half of patients also have marked systemic disease. While the aetiology is not fully understood, clues have been given by experiments in vivo. Autoantibodies to SSA(Ro) are particularly common in subacute cutaneous LE, and blebs containing SSA(Ro) and other intracellular antigens form on the nuclear surface of irradiated keratinocytes. SSA(Ro) autoantibodies can activate complement. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and autoantibody binding to SSA(Ro) are enhanced by oestradiol, perhaps accounting for the increased prevalence of subacute cutaneous LE in women. Unusually, drugs may cause subacute cutaneous LE, producing a more widespread rash than in the idiopathic disease. Patients with subacute cutaneous LE are often photosensitive. The skin lesions are sharply marginated psoriasiform plaques, sometimes annular, lying on the forehead, nose, cheeks, chest, hands and sun-exposed surfaces of the arms and forearms. They tend to be symmetrical and are hard to tell from discoid LE, or SLE with widespread discoid lesions. As in SLE, the course is prolonged. The skin lesions are slow to clear but, in contrast to discoid LE, do so with little or no scarring. Systemic disease is frequent, but not usually serious. SSA(Ro) can cross the placenta and children born to mothers who have, or have had, this condition are liable to neonatal LE with transient annular skin lesions and permanent heart block. The morphology is characteristic, but lesions can be mistaken for psoriasis or widespread discoid LE. Annular lesions may resemble tinea corporis (p. 240) or figurate erythemas (p. 141). Patients with subacute cutaneous LE should be evaluated in the same way as those with acute SLE, although deposits of immunoglobulins in the skin and antinuclear antibodies in serum are present less often. Many have antibodies to the cytoplasmic antigen SS-A(Ro) and SS-B(La). Subacute cutaneous LE does better with antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine (Formulary 2, p. 424), than acute SLE. Moderate potency topical corticosteroid creams help, and oral retinoids (Formulary 2, p. 420) are also effective in some cases. Systemic steroids may be needed too, especially if there are signs of internal disease. This is the most common form of LE. Patients with discoid LE may have one or two plaques only, or many in several areas. The cause is also unknown but UVR is one factor. Plaques show erythema, scaling, follicular plugging (like a nutmeg grater), scarring and atrophy, telangiectasia, hypopigmentation and a peripheral zone of hyperpigmentation. They are well demarcated and lie mostly on sun-exposed skin of the scalp, face and ears (Figures 10.1 and 10.3). In one variant (chilblain LE) dusky lesions appear on the fingers and toes. Figure 10.3 Red scaly fixed plaques of discoid lupus erythematosus (LE). This degree of scaling is not uncommon in the active stage. Follicular plugging is seen on the nose. The disease may spread relentlessly, but in about half of the cases the disease goes into remission over the course of several years. Scarring is common and hair may be lost permanently if there is scarring in the scalp (Figure 10.4). Whiteness remains after the inflammation has cleared, and hypopigmentation is common in dark-skinned people. Discoid LE rarely progresses to SLE. Figure 10.4 Discoid LE of the scalp leading to permanent hair loss. Note the marked follicular plugging. Psoriasis is hard to tell from discoid LE when its plaques first arise but psoriasis has larger thicker scales, and later it is usually symmetrical and affects different sites from those of discoid LE. Discoid LE is common on the face and ears, and on sun-exposed areas, whereas psoriasis favours the elbows, knees, scalp and sacrum. Discoid LE is far more prone than psoriasis to scar and cause hair loss. Most patients with discoid LE remain well. However, screening for SLE and internal disease is still worthwhile. A skin biopsy is most helpful if taken from an untreated plaque where appendages are still present (Figure 10.5

Connective Tissue Disorders

Disease

Autoantibody

Frequency

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Double-stranded DNA

Sm antigens (U1, U2, etc.)

Phospholipid

50–70%

15–30%

10–20%

Drug-induced lupus

Nuclear histones

Common

Subacute cutaneous Lupus

SS-A(Ro)

SS-B(La)

50–70%

20–30%

Dermatomyositis

Jo-1

Mi-2

20–30%

(5–10%)

Systemic sclerosis

SCL–70 (topoisomerase 1)

20–30%

CREST syndrome

Centromere

20–30%

Mixed connective tissue disease

U1-RNP

100%

Lichen sclerosis

Extracellular matrix protein 1

Uncertain

Localized disease

Intermediate type

Aggressive multisystem disease

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Subacute lupus erythematosus

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Adult dermatomyositis

Localized scleroderma

Diffuse scleroderma

Morphoea

CREST syndrome

Systemic sclerosis

Lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Cause

Presentation

Course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Malar rash

Discoid plaques

Photosensitivity

Mouth ulcers

Arthritis

Serositis

Renal disorder

Neurological disorder

Haematological disorder

Immunological disorder

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

Investigations

Test

Usual findings

Skin biopsy

Degeneration of basal cells, epidermal thinning, inflammation around appendages

Skin immunofluorescence

Fibrillar or granular deposits of IgG, IgM, IgA and/or C3 alone in basement membrane zone

Haematology

Anaemia, raised ESR, thrombocytopenia, decreased white cell count

Immunology

Antinuclear antibody (higher titres typical of SLE rather than cutaneous LE), antibodies to double-stranded DNA, false positive tests for syphilis, low total complement level, lupus anticoagulant factor, ENA screen, sm antibody

Urine analysis

Proteinuria or haematuria, often with casts if kidneys involved

Tests for function of other organs

As indicated by history, but always test kidney and liver function

Treatment

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Presentation

Course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Presentation

Course

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree