43 Conjoined twins

Synopsis

Conjoined twins are one of the most uncommon congenital anomalies, with an incidence between one in 50 000 and one in 100 000 births

Conjoined twins are one of the most uncommon congenital anomalies, with an incidence between one in 50 000 and one in 100 000 births

Conjoined twins are classified by dorsal or ventral site of fusion and anatomic region of fusion

Conjoined twins are classified by dorsal or ventral site of fusion and anatomic region of fusion

Separation of conjoined twins requires a multidisciplinary team approach

Separation of conjoined twins requires a multidisciplinary team approach

Understanding the shared anatomy through preoperative imaging studies and investigations is critical to successful separation

Understanding the shared anatomy through preoperative imaging studies and investigations is critical to successful separation

Careful planning and insertion of tissue expanders is almost always necessary to accomplish wound closure

Careful planning and insertion of tissue expanders is almost always necessary to accomplish wound closure

Intensive care monitoring and support, nutritional supplementation, and pressure-reducing strategies are essential for successful separation.

Intensive care monitoring and support, nutritional supplementation, and pressure-reducing strategies are essential for successful separation.

Historical Perspective

Society has been fascinated with conjoined twins since antiquity. Attitudes have evolved from suspicion and fear with subsequent ostracization from society on religious grounds, to exploitation and exhibitionism, to the modern-day intense media interest in rare medical conditions, treatments, and cures. In classical times, gross anomalies were considered a warning from the gods. Scholars, including Aristotle and Hippocrates, thought the unborn child was susceptible to external stimuli. Thus, maternal impressions, and sins of the parents, were often blamed for “monstrous births,” and conjoined twins were considered prototypical examples. Those who survived were often treated as religious and social outcasts.1–3

Early theories focused on anatomic factors and male fertility. Aristotle, in his textbook, De Generation Animalium, theorized that conjoined twins were the result of a womb that was too small and constrained the seed of twins, causing them to become congested and joined. Hippocrates reportedly believed that too great a quantity of seed was responsible for multiple births and conjoined twinning, whereas one “lacking in quantity” was thought to lead to limb agenesis and missing body parts.3

The earliest examples of conjoined twins are artifactual and include a 17.2-cm marble statue of female parapagus twins dating from the sixth millennium bc. Called the “double goddess,” this portrayal of the sisters of Catathoyuk is housed in the Antolian Civilization Museum in Ankara, Turkey.4 Another early representation is a stone carving of pygopagus twins discovered in Fiesole, Italy, dated to 80 bc and currently housed in the San Marco Museum in Florence5,6 (Fig. 43.1).

Fig. 43.1 Stone carving of pygopagus twins dated to ∼80 bc, Fiesole, Museo San March, Florence, Italy.

(Reproduced from Spitz L. Surgery for conjoined twins. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:230–235.)

The first well-documented case of conjoined twins is that of the maids of Biddendon, Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst, who were born in England in the year 1100 and survived into adult life, joined laterally from hips to shoulders. When one twin died at the age of 34 years, the second twin refused to be separated from her sister, saying, “as we came together we will also go together,” and subsequently died 6 hours later.7 The earliest documented case of craniopagus twins is of girls born near Worms, Germany in 1495 who lived to the age of 10 years and whose birth was interpreted at the time as a sign of God’s displeasure. They were joined at the forehead, as depicted in a woodcut circa 14968,9 (Fig. 43.2).

Perhaps the most famous pair of conjoined twins is Eng and Chang Bunker, who were born in Siam in 1818 (Fig. 43.3). They were taken to the US by a traveling Scottish merchant, and they gained notoriety there after PT Barnum exhibited them as “Siamese twins” in his travelling Barnum and Bailey Circus – hence the derivation of the colloquial term. Despite their abdominal connection, they married sisters, fathered 22 children, and lived together for 63 years.10

The earliest attempt at separation is recorded as occurring in Kappadokia, Armenia in 970 ad. This was an unsuccessful attempt to separate male ischiopagus twins at age 30 after one twin died.5 The first reported successful separation of conjoined twins was performed in 1689 in Basel, Switzerland. The surgeon, Johannes Fatio, separated a pair of omphalopagus twins. Koenig, another surgeon who was an observer at the procedure, published the case as his own, and thus is frequently credited with the first successful conjoined twin separation.11

Basic science/disease process

Incidence

Conjoined twins are one of the most uncommon congenital anomalies. The typical form of monozygotic twinning occurs in 4 per 1000 live births, and dizygotic fraternal twinning in approximately 10–15 per 1000. Twin births therefore occur in about 1 in 90 live births.12 The incidence of conjoined twins has been estimated at between one in 50 000 and one in 100 000 pregnancies. Spencer has reported that 1% are stillborn, and 40–60% die shortly after birth, so the true incidence is closer to 1:200 000 live births.5,13 Recent reports of prenatally diagnosed conjoined twins indicate that more than a fourth of cases die in utero and one-half die immediately after birth, leaving only 20% potential survivors who are candidates for separation.14 In all reports, females predominate over males by approximately three to one. However, in reports of stillborn conjoined twin pairs, males predominate over females.5,10,15–17

Classification

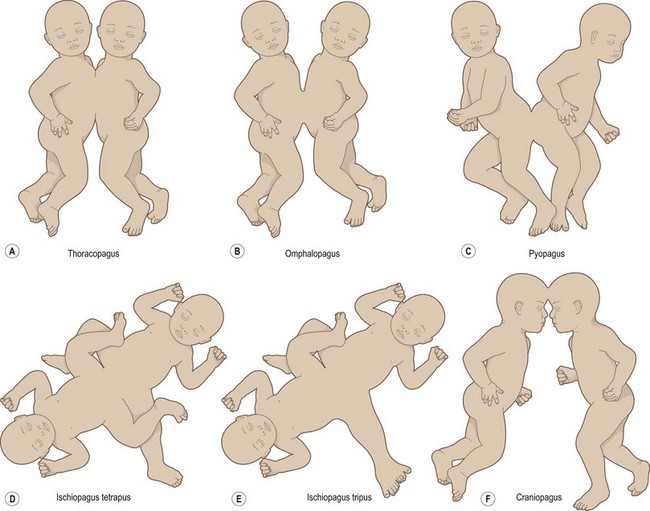

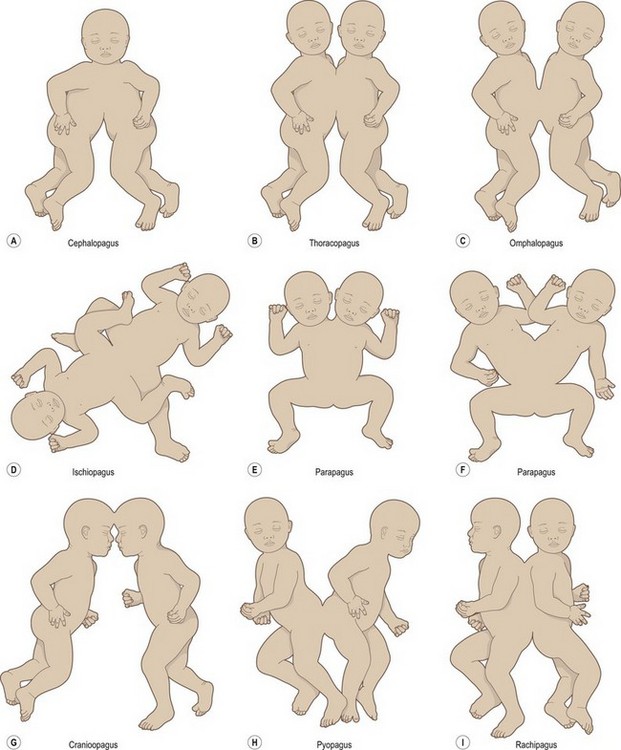

A number of classification systems exist and each categorizes conjoined twins by their most prominent site of union together with the suffix “pagus,” a Greek word meaning “that which is fixed.” The most commonly used system, both clinically and historically in the literature, was adapted from that proposed by Potter and Craig, and simplified to include the five most common forms of conjoined twinning, listed here in order of decreasing frequency: thoracopagus, omphalopagus, pygopagus, ischiopagus, and craniopagus.18 These five types are summarized below and illustrated in (Fig. 43.4). Additionally, the number of shared anatomic structures can be described with the prefixes “di-,” “tri-,” and “tetra-,” combined with the involved parts, “prospus” (face), “brachius” (upper extremity), and “pus” (lower extremity). For example, ischiopagus twins may have three (tripus) or four (tetrapus) legs.

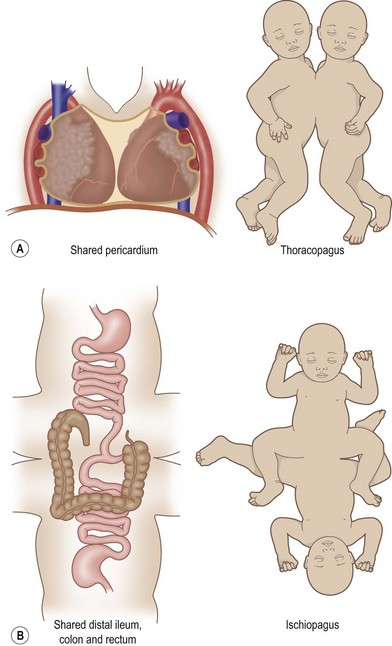

The thoracopagus type is the most common, occurring in 74% of cases. Infants with this form of twinning face each other, have major junctions between the chest and abdomen, and may have conjoined livers, hearts, and upper gastrointestinal structures (Fig. 43.5; case 6, below). Separation may be limited by the degree of cardiac involvement. Conjoined six-chamber hearts are common in thoracopagus twins and have never been separated successfully; only a single successful case of separation of twins with conjoined atria has been reported.19 Advances in prenatal diagnosis and the development of fetal surgery have improved perinatal survival in cases where separation is deemed appropriate. For example, the EXIT procedure (ex utero intrapartum treatment) has been recently used at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in the separation of thoracopagus twins. In this case, one twin had a normal heart that perfused a co-twin with a rudimentary heart, and EXIT allowed prompt control of the airway and circulation prior to clamping the umbilical cord, leading to survival of the normal co-twin.14

In omphalopagus twins, there is fusion in the abdominal area with variable connections of the liver, biliary tree, and gastrointestinal tracts. In isolated omphalopagus forms, there is no cardiac connection (case 8, below).

Pygopagus twins are joined at the level of the sacrum and commonly face away from each other. There is usually a shared spinal cord, and the perineal structures and rectum also may be fused. Pygopagus twins represent about 17% of conjoined twins.12

In the ischiopagus type, the junction is at the pelvic level with sharing of the genitourinary structures, rectum, and liver (Fig. 43.5) (cases 5 and 7, below). These twins may each have a single normal leg and a common fused leg, referred to as a tripus, or four legs may be present. The tripus, when present, usually has dual neural and vascular supply and preoperative determination of perfusion is important in planning separation. Often, the tripus is sacrificed and the soft tissue used for closure of each twin, leaving each with a single leg. In a unique case, Zuker et al. reported successful transplantation of an entire extremity from a dying twin to her sister, thus leaving the surviving one with two functional legs.20

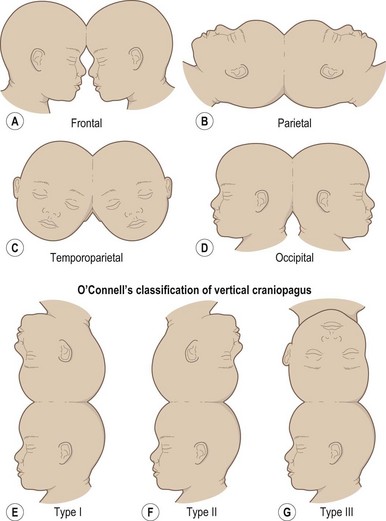

The least common and perhaps the most difficult to separate is the craniopagus type because the cranial union often involves a variety of neural and vascular connections.12,21,22 Craniopagus twins represent 2–6% of conjoined twins and occur with an incidence of one in 2.5 million births.9 They can share scalp, calvarium, dural sinuses, and surfaces of the brain, but the face, foramen magnum, and spine remain separate. Even when the cerebral cortices are contiguous, craniopagus twins do not share neuronal pathways, as demonstrated by completely independent behavior and by electroencephalogram studies. Facial and skull asymmetry can occur, as well as other intracranial and extracranial abnormalities. The site of fusion can vary significantly, and rotation about this site of union can produce a variety of anatomic orientations.3,8,21,23 A number of authors have classified craniopagus twins by the site, degree of fusion, or alignment of the twins.24,25 The more common phenotypic variations described in case reports in the literature are illustrated in (Fig. 43.6).

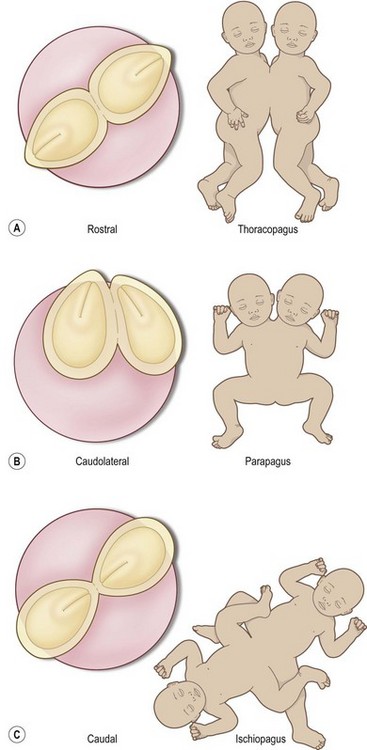

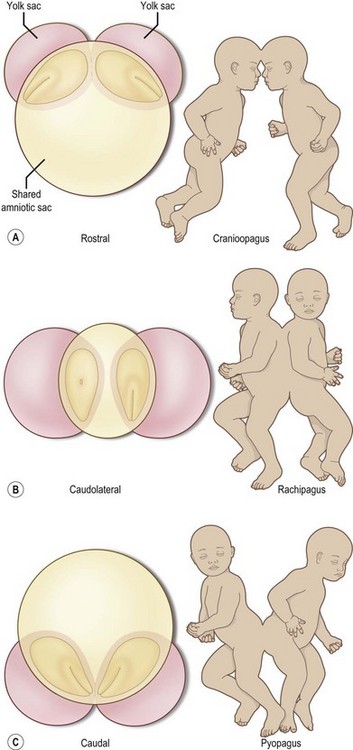

An alternative classification system was proposed by Spencer, based on the analysis of embryologic data and the teratology of over 1200 cases. She divided conjoined twins into dorsal and ventral forms of union, joined in one of eight anatomic sites (Fig. 43.7). This classification system specifically defines and restricts the anatomy of fusion between the different types of conjoined twinning, thus attempting to standardize the nomenclature for purposes of predicting separability, surgical planning, and outcomes after surgery, as well as for consistent documentation for research purposes.26 In Spencer’s embryologic classification system, ventral unions are oriented ventrally or ventrolaterally, and the union always includes the umbilicus, whereas dorsal unions are united dorsally or dorsolaterally and do not include the thoracic or abdominal viscera or the umbilicus. Ventral unions are further subdivided into rostral, caudal, or lateral. These eight types with their definitions and restrictions are listed below.26

Fig. 43.7 (A) The eight types of conjoined twins, as classified by Rowena Spencer26 based on the theoretical site of union and divided into ventral and dorsal forms of junction. (B) Parapagus conjoined twins with a single pelvis.

Dorsal

6. Craniopagus: united on any portion on the skull except the face or foramen magnum, and the trunks are never united.

7. Pygopagus: sharing sacrococcygeal and perineal regions, and sometimes the spinal cord.

8. Rachiopagus: fused dorsally above the sacrum, and exceedingly rare.

Asymmetrical forms of conjoined twinning often occur, resulting in a smaller and larger twin; these are termed “parasitic” followed by their closest classification. When one twin is significantly smaller and less well developed, it is often malnourished and has other physiologic problems which can complicate potential separation. On some occasions, the smaller twin may die and much of the deceased twin may be absorbed. Conjoined twins whose union and anatomy are intermediate between different types are termed “atypical conjoined twins.”26

Etiology

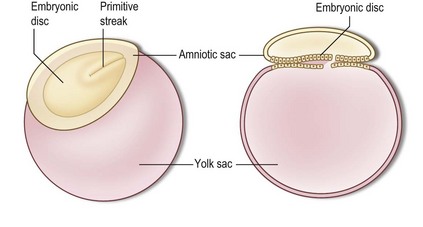

Two theories have been proposed to explain the embryology resulting in conjoined twins. The classic theory of incomplete fission, described by Zimmerman,27 proposes that there is incomplete separation of the embryonic discs of twins arising from a uniovular gestation between 13 and16 days after fertilization. More recently, Spencer28 proposed an alternative theory of secondary fusion of two originally separate monovular embryonic discs. This theory postulates that, during the third or fourth week of development, previously separate embryonic discs reunite either dorsally or ventrally at specific sites where the surface ectoderm is either absent or normally programmed to fuse or break down. These sites include the anlage of the heart, the diaphragm, the oropharyngeal and cloacal membranes, the neural tube, and the periphery of the embryonic discs, each site corresponding to specific types of conjoined twinning. The unions are always homologous, meaning the fusion occurs head to head, tail to tail, front to front, back to back, or side by side but never head to tail or front to back. Spencer’s “spherical theory” proposes that conjoined twins united dorsally “float” in a shared amniotic cavity, and those united ventrally “float” on the sphere of a shared yolk sac. In both cases, they can be oriented from rostral to caudal, depending on the relative temporal–spatial relationship of the embryonic discs during fusion28 (Fig. 43.8).