9 Comprehensive trunk anatomy

History

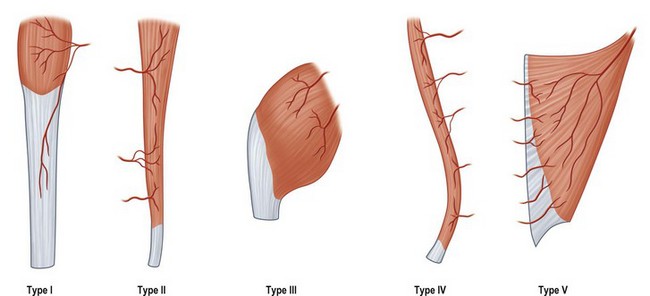

Multiple authors sited in plastic surgical literature have attempted to classify bone, muscles, fascia and skin, based on the vascular supply to these tissues and the flaps that can be derived from them. Few of these has held more steadfast than Mathes and Nahai’s classification of the vascular anatomy of muscles (Fig. 9.1)1 and Ian Taylor’s angiosomes of the skin.2 Today, these authors provide the basis for much of the current understanding of tissue and vascular anatomy that is the key to successful plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Basic science and disease process: embryology of the trunk

In the third week of gestation, formation of the axial skeleton begins. The bony skeleton, muscles, fascia and skin are derived from mesodermal somites bordering the central notochord. Pluripotent mesenchymal cells differentiate into fibroblasts, osteoblasts and chondroblasts and other progenitor cells that will build the tissues of the fetal body. The axial skeleton consists of skull, vertebral column, ribs and sternum. The appendicular skeleton includes the pelvic and pectoral girdles. The skeleton begins to chondrify in the 6th week of gestation. The process of ossification can last from a few months gestation until young adulthood. Progenitor skeletal muscle cells divide into dorsal (epaxial) and ventral (hypaxial) divisions along with a corresponding spinal nerve. The extensor muscles of the vertebral column, derived from the epaxial myotomes, are innervated by posterior rami of the spinal nerves. All of the other muscles of the trunk are derived from the hypaxial myotomes and are innervated by the ventral rami. Most skeletal muscles are fully developed by birth.3

Angiogenesis begins in the 3rd week of gestation. Primordial blood vessels begin to form in the extraembryonic mesenchyme of the yolk sac. Mesenchymal cells differentiate into angioblasts, forming aggregate blood islands. These begin to coalesce into primitive endothelium. Near the end of the 3rd week, this same process is evident within the embryo itself and by the beginning of the 4th week, the embryo has a functional circulatory system.3 At birth, the main vessels and perforators to the skin are present. The entire body is lined by superficial fascia4 that lies just below the dermis and is surrounded by varying amounts of adipose tissue. It serves to encase, support and protect the fatty and muscular layers of the body and to support the overlying skin in the dynamic movements of the underlying muscle. In certain areas it is adherent to the deep fascia or periosteum and at these places the body contour is defined by creases and convexities. Where there are bulges and plateaus the connections between superficial and deep systems are looser. As an individual grows, vessels stretch from their origins, usually in areas near joints or fixed fascial planes of the body. Taylor noted that areas that were mobile had cascades of arterial supply that tended to originate from the fixed areas distant from the tissue supplied by the vessel. He asserted that these perforators were present at birth and grew along the fascial planes and stretched as the individual grew and developed.2

Back

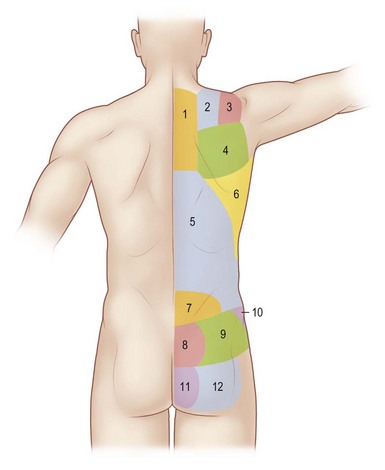

The back provides support for the head and shoulders while walking upright. Near the midline, the paraspinous muscles run in a vertical fashion and are mainly responsible for spinal support and protection. Moving laterally and superficially, muscles become broad and are responsible for movement of neck, shoulders, hips and extremities. The dermis of the back is thicker than any other place on the body. Dense adhesions between the superficial fascia and the skin of the back prevent shearing of the tissues. The spine has dense fascia surrounding the spinal processes and attaches to the dermis. This creates the central midline. Palpable at the base of the neck is the vertebra prominens of the C7 spinous process. The root of the scapular spine is at the level of T3 and the angle of scapula is at T7. Typically, the spinous process of T12 is palpable. The bilateral iliac crest forms the hips at the level of L4. The posterior inferior iliac spine is parallel to S2 (Fig. 9.2).

The thoracolumbar fascia is the investing fascia of the back. It encases the paraspinous muscles as well as the quadrates lumborum. It is continuous with the nuchal fascia of the neck, attaches medially to the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae, laterally to the angles of the ribs and inferiorly to the posterior iliac spine. It is supplied by the lumbar and thoracic perforators, as well as the distal end arteries of the superior gluteal artery inferiorly and the thoracodorsal artery superiorly.5

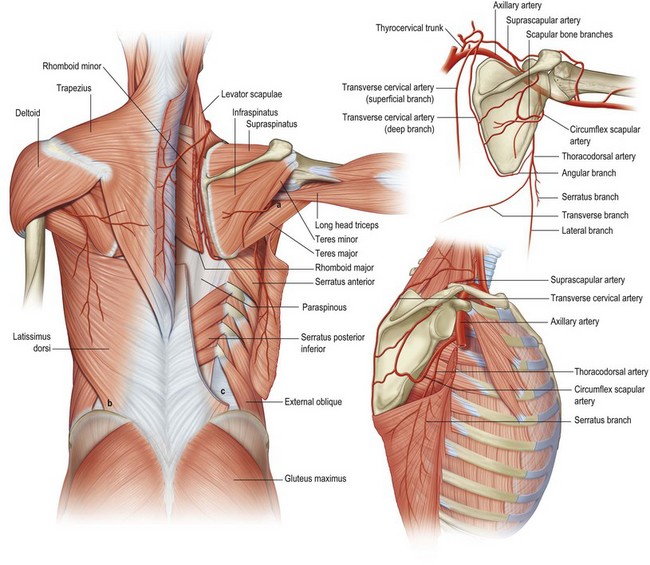

The broad flat latissimus muscle can usually be seen on both sides of the lower midback in thin, muscular individuals. The posterior axillary fold is formed by its tendon as it crosses from the back to insert on the humerus. The triangular space of the posterior axilla is defined by the teres minor superiorly, teres major inferiorly and the long head of the triceps laterally (Fig. 9.3). Through it courses the circumflex scapular artery and two venae comitantes.

There are two spaces referred to as the lumbar triangle. These are areas of the back that do not contain all of the muscular layers. The inferior or petit triangle is bound by the latissimus medially, the external oblique laterally and the iliac crest inferiorly. Its base is comprised of the internal oblique muscle (Fig. 9.3). The Superior or Grynfeltt triangle is created by the 12th rib superiorly, the quadrates lumborum medially and the internal oblique laterally. The floor is comprised of the transversalis muscle (not shown). No vessels or named nerves travel through these spaces. The lumbocostoabdominal triangle is formed by the external oblique, the serratus posterior inferior, the erector spinae, and the internal oblique.

Vascular anatomy

The dominant blood supply to the trapezius is via branches of the transverse cervical artery. Originating from the thyrocervical trunk, it passes through the posterior triangle of the neck to the anterior boarder of the levator scapulae muscle.7 Here, it divides into deep and superficial branches. Upon entering the muscle the superficial branch divides again into an ascending and descending branch. It is the descending branch, sometimes referred to as the superficial cervical artery (SCA), which supplies the middle and lateral portions of the trapezius. Once the deep branch separates from the superficial branch it courses below the levator scapulae to the undersurface of the rhomboids. A perforating branch emerges from between the rhomboid muscles and becomes the main supply to the trapezius inferior to scapular spine (Fig. 9.3). The deep branch, also referred to as the dorsal scapular artery (DSA), supplies the lower middle and inferior portion of the trapezius and the skin paddle above and lateral to it overlying the latissimus. Through the years there have been many anatomical studies attempting to define the blood supply to the trapezius. Some of the confusion arises simply from nomenclature. In 2004, Hass published a large cadaver study, finding, in nearly 45% of specimens, the DSA arose from the subclavian artery or costocervical trunk. In the remaining 55%, the DSA formed a trunk with the SCA and, or the suprascapular artery. The trapezius also receives segmental blood supply medially from the intercostal arteries 3–6, leading some investigators to classify this muscle as Mathes and Nahai type V.8

The subscapular artery arises from the third portion of the axillary artery and branches into the circumflex scapular and the thoracodorsal arteries. Occasionally the circumflex scapular arises directly from the axillary artery. The circumflex scapular artery passes through the triangular space and gives off perforating branches to the superior lateral boarder of the scapula. There is rarely a defined medullary branch, however, a segment of bone measuring 10–14 cm along the lateral boarder, can usually be harvested reliably on these small perforators.9 The main artery goes on to divide into a small ascending branch, which is occasionally absent, and more robust transverse and descending branches. These supply the scapular and parascapular flaps, respectively. These arteries run in the subcutaneous plane and are paralleled by two venae comitantes. The venous outflow follows the subscapular system and eventually drains into the axillary vein.10

After branching from the subscapular artery, the thoracodorsal artery passes along the deep surface of the latissimus and continues caudally 1–4 cm posterior to the lateral boarder of the muscle. As the artery descends, a branch or branches supply the lower portion of serratus anterior. After this, it divides into a lateral (or descending) branch and a transverse (or horizontal) branch. Angrigiani described three musculocutaneous perforators that reliably left the lateral branch of the thoracodorsal artery piercing the latissimus muscle and supplying the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lateral infrascapular back. The proximal perforator exits 8 cm below the posterior axillary fold and 1–4 cm posterior to the lateral boarder of the muscle. Other smaller perforators were found along a similar trajectory inferiorly and obliquely located along the lateral boarder of the latissimus (Fig. 9.3).11

Seneviratne et al. described the angular artery as a branch from the subscapular system that supplied the lower lateral segment and the angle of the scapula. It can arise from the latissimus or serratus branch of the thoracodorsal artery or at a trifurcation with both vessels. From its origin to where it penetrates the bone measures approximately 7 cm and is reliably found between the teres minor and serratus anterior on its way to the dorsal surface of the scapular angle. This artery allows a strip of bone up to 3 cm of the lateral scapular angle and 6 cm of the vertebral surface to be harvested as a composite graft with muscle, fascia or skin.12

The intercostal and lumbar arteries supply much of the skin and musculature of the midback. Perforators emerging from these vessels pass through the paraspinous muscles in three adjacent columns that parallel the spinous processes laterally at 3, 5 and 8 cm. These segmental perforators have longitudinal anastomotic connections to one another.13

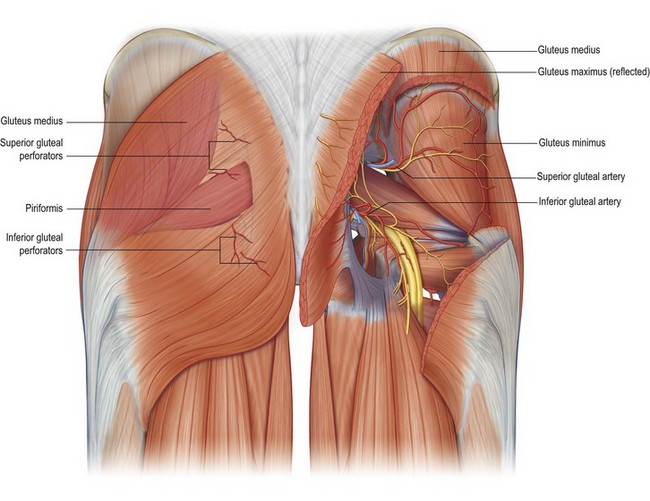

The superior gluteal artery arises from the internal iliac artery and passes through the greater sciatic foramen. At approximately 6 cm below the PSIS and 4–5 cm lateral to the sacral midline, the artery passes between the gluteus medius and piriformis muscle to enter the gluteus maximus. It sends nutrient branches to the muscle and continues to the overlying skin and soft tissue. The inferior gluteal artery also arises from the internal iliac artery. It passes through the lesser sciatic foramen, inferior to the piriformis muscle to supply the lower gluteal skin and soft tissue (Fig. 9.4).

Chest

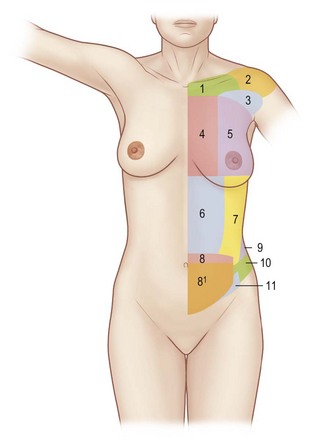

The clavicle and manubrium create the cranial boarder of the chest. The midpoint of the clavicle defines a plumb line drawn down the anterior chest and is referred to as the midclavicular line. The xiphoid and the synchondrosis of ribs 7–10 create the caudal boarder of the chest. The diaphragm is attached to the posterior surfaces of the xiphoid process and the lower six ribs and costal cartilages. Laterally, the chest is bordered by the anterior axillary fold which is created by the pectoralis major tendon as it inserts on the humerus (Fig. 9.5). The deltopectoral triangle is pierced by the cephalic vein as it joins the axillary vein. It is bound medially by the clavicle, superiorly by the deltoid and inferiorly by the pectoralis major muscle. Spanning the triangle and coursing beneath the pectoralis major is the clavipectoral fascia; a thick, dynamic fascial sling. Lateral to the triangular space discussed in the back is the quadrangular space of the axilla. Its boundaries include the teres major inferiorly, teres minor and subscapularis superiorly, the long head of triceps medially and the surgical neck of the humerus laterally. Through it passes the posterior circumflex humeral artery and axillary nerve.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree