Complications and Secondary Corrections After Breast Reduction and Mastopexy

Scott L. Spear

Karen Kim Evans

Introduction

The relationship between reconstructive and cosmetic surgery is clearly at play in the case of breast reduction and mastopexy. The various methods of glandular excision, incision patterns, and type of neurovascular pedicle offer advantages and disadvantages for each patient. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the results of these techniques meet or even surpass patient expectation both in terms of symptomatic improvement and cosmetic outcome. Although proper patient selection for each method is a critical component for successful outcome, a thorough understanding of the complications of breast reduction and mastopexy and how to avoid them can also be very helpful. This is particularly true as surgeons attempt newer techniques, including shorter scars and different pedicle design.

Nipple Loss

Although rare, nipple loss is one of the most devastating complications of breast reduction. The reported incidence varies from 0 to 10%, depending on whether the author includes partial nipple necrosis and complete nipple loss when determining the frequency of this mal-occurrence (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14). As surgical skill, techniques, and understanding of the anatomy of the rich blood supply to the nipple from both cranial and caudal perforators have advanced, the incidence of nipple loss has decreased (15). Traditionally recognized “safer” and more familiar techniques, such as the inferior pedicle and free nipple grafting in very large reductions, have already become well accepted methods to minimize nipple loss. These techniques are the de facto benchmark standards that other techniques are measured against.

For moderate to large reductions, vertical scar patterns and/or superomedial pedicle techniques have been shown in some preliminary reviews to reliably protect the nipple (16,17). Nipple loss has been reported even in cases of mastopexy and especially in the setting of secondary procedures surrounding thin, poorly vascularized tissues. Of course, the combination of mastopexy with augmentation or mastopexy as a secondary procedure inherently increases complications such as nipple loss (18). It is generally recognized that secondary breast reduction should use the same pedicle as in the original procedure; however, more recent reports suggest that using a different pedicle may be “safe” (19,20,21,22). We would caution against this broad statement and suggest that it is imperative to maximize the blood supply to the nipple in the setting of secondary reduction mammaplasty by using the same pedicle if it is known and if the nipple is to be moved any significant amount. Moreover, we perform direct excision rather than undermining flaps and caution that previous scars, even within the breast parenchyma, are a permanent obstruction to blood flow (20). As a general principle, in secondary cases, it is wise to avoid creating risky pedicles or flaps and to maximize the blood supply to the nipple and flaps as much as possible.

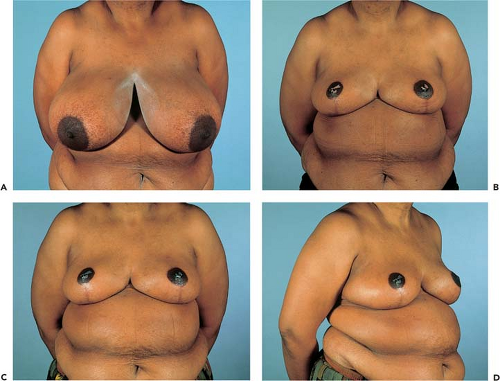

Intrinsic patient risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, all of which are common in this patient population, further increase the risk of nipple loss. Avoiding nipple loss begins with patient selection and choosing the safest possible techniques in high-risk patients. Encouraging patients to lose weight and stop smoking could reduce the risk to some extent. Many times, insurance companies are reluctant to cover breast reduction for patients who are obese. In high-risk patients, including those with resections greater than 2 kg, severe ptosis, or with body mass index (BMI) greater than 35, reduction using free nipple graft should be considered, either as the primary or as a back-up procedure. Focusing on the quality of the recipient bed, careful handling of tissues and avoidance of hematoma or seroma under the graft should reduce the risk of nipple loss to 1 to 2%.

At the time of surgery, a doubtful or struggling nipple can be converted to a graft if the blood supply appears sluggish on the table. Even postoperatively, when in doubt, the nipple can still be converted to a nipple graft. Although it should be obvious that the sooner this is done, the better, there is no scientific evidence for a time limit to this opportunity for nipple salvage.

It is important to consider the etiology of an ischemic nipple, inspect the breast for hematoma, and release tight periareolar sutures. Some surgeons have even described using leech therapy or nitropaste on an early, struggling nipple. Rather than resort to early debridement, in the case of a struggling nipple, for the first few weeks, one should consider treating a compromised nipple conservatively. In addition to leeches and nitropaste, other conservative therapy includes hyperbaric oxygen, moist dressings, and systemic antibiotics to cover skin flora. Although lacking absolute scientific proof, we have been particularly gratified by the effects of hyperbaric oxygen if instituted within 24 hours of surgery and continued for 5 to 7 days. Debriding necrotic tissue should be done carefully and with deliberation because the nipple will often re-epithelialize from deeper dermal elements.

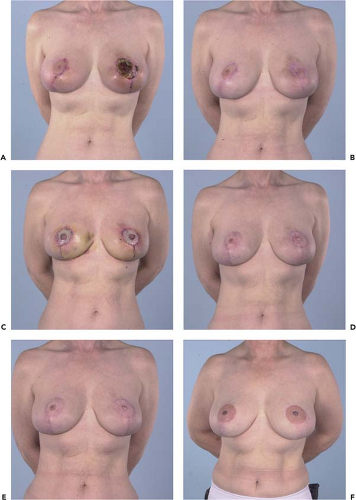

Once the wound has healed, the nipple-areola complex can be reconstructed using techniques similar to those used in breast reconstruction. These may include tattooing for the areola (Fig. 105.1), full-thickness skin grafting, contralateral nipple composite grafts, nipple reconstruction using local flaps (Figs. 105.2 and 105.3), dermal fat grafts, or filler injections into the nipple.

Scars

Although nipple loss is a particularly devastating complication, unattractive or disfiguring scars are much more common and

can also be a serious problem. Despite the universal desire of patients for scarless surgery, it is not possible. It is true that a number of abbreviated scar techniques are currently being used, and these all promote less or shorter scars, but they have not been proven to provide consistently better cosmetic results, or even better scars.

can also be a serious problem. Despite the universal desire of patients for scarless surgery, it is not possible. It is true that a number of abbreviated scar techniques are currently being used, and these all promote less or shorter scars, but they have not been proven to provide consistently better cosmetic results, or even better scars.

Although the choice of procedure and surgical skill are important, the underlying nature of the patient’s tissues and skin are often the critical determinants of the quality of the scar. Young, dark-skinned or thick-skinned women, including Asian, African, and some Caucasian women, are often prone to poor scars. It is ironic that older patients with typically thinner skin, who usually care less about the scar, produce the best scars, whereas younger patients for whom scars are more critical often scar the worst. To help with the appearance of the scar, we have abandoned the use of braided Vicryl suture in the dermis due to its high inflammatory potential and use instead only monofilament dissolvable suture such as Monocryl.

The short-scar techniques, including vertical (Lassas or Lejour) reduction, Marchac, SPAIR, Spear modification of the SPAIR, L shaped (De Longis), Renault reduction, central pedicle, Hall Finlay’s superomedial pedicle, and so on all attempt to shorten or avoid the inframammary component of the scar. Many reviews (3,7,11,12,14,16) suggest these techniques have evolved into safe, reliable methods of reduction with good aesthetic results and minimal major complications. The disadvantages to these types of minimal scar reduction include a steep learning curve, less reproducible outcomes, and the possibility of a high rate of “touch-up” procedures. Initially, there were reports of persistent vertical scar dog ears, teardrop nipple deformities, and persistent axillary fullness. It is safe to say that these techniques have their greatest appeal in the younger patient needing a moderate to small reduction, where obtaining significantly shorter or less scars is worth the added complexity.

We recommend standard postoperative scar management, including massage, silicone sheeting, topical vitamin E, and sunscreens. Poor scars, including keloids and hypertrophic scars, may be injected with dilute Kenalog or even managed with surgical revision (Fig. 105.4).

Figure 105.2. A 56-year-old who had a bilateral mastopexy at another institution with bilateral nipple necrosis. A and B: Preop photos showing nipple necrosis and following debridement and dressing changes. C: One week after bilateral nipple-areolar revision using the remaining nipple-areolar complex and full-thickness skin grafts and bilateral areolar tattoo. D–F: Three months, 6 months, and nearly 2 years postoperative.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|