Introduction

When you examine a skin lesion with dermoscopy, it might be obviously benign or malignant. There is also a gray zone of equivocal lesions. Gray-zone lesions will commonly be encountered by the novice dermoscopist. To help deal with this common situation, we offer a few suggestions. Learn the basics, practice the technique as often as possible, and develop a dermoscopic differential diagnosis.

You have to be able to think things through logically, weighing the pros and cons for each criterion or pattern that you see. Coming up with a tentative dermoscopic diagnosis, or in many cases, a dermoscopic differential diagnosis, is the end of the process.

For example, are the round to oval yellow dots and globules you see the milia-like cysts of a seborrheic keratosis or the follicular ostia of a melanocytic lesion? What a difference that distinction could make. You could be dealing with a seborrheic keratosis or a lentigo maligna. Are those the brown dots and globules of a melanocytic lesion, or the pigmented follicular openings of a seborrheic keratosis? You notice that the lesion has some blood vessels. Are they the thickened branched vessels of a basal cell carcinoma or the irregular linear vessels that can be found in melanomas?

We regret to inform you that you will encounter difficult lesions—lesions that even the most experienced dermoscopist will not feel confident about. That is the state of the art as it exists today. There are infinite variations of criteria, patterns, and lesions. The scenarios in this final chapter demonstrate the dermoscopic thought process we employ. Focus your attention, use what you have learned in the first two chapters of the book, and you will find that you will learn and grow with each case. Do not be intimidated by what you see. We guarantee that you can master this technique. You will develop your own style of dermoscopic analysis and find that dermoscopy will become an essential part of your practice. You will not be able to practice without it!

Pediatric scenario

General principles

- •

Melanoma in childhood is exceedingly rare, and the great majority of melanocytic skin lesions in prepubertal children are benign and do not require any special attention. The dermoscopic criteria of childhood nevi are the same as in other age groups, but in most cases, childhood nevi reveal a globular pattern.

- •

The most problematic skin tumors in the pediatric patient are large to giant congenital melanocytic nevi and atypical Spitz tumors.

- •

Large to giant congenital nevi represent the most important risk factors for melanoma in prepubertal children, although the risk is still low (<1%). Because melanoma associated with large to giant congenital melanocytic nevi often develops deep in the dermis or in the central nervous system, dermoscopy is of limited benefit in the early diagnosis of melanoma.

- •

The risk for melanoma in small to medium congenital melanocytic nevi is not established, but they should be kept under regular surveillance. Biopsy is indicated in the case of significant atypical structural changes.

- •

There are no definitive guidelines about the management of Spitz nevi, and there are controversies about whether to follow up or excise these nevi. However, flat pigmented Spitz nevi (commonly also called Reed nevi) with a stereotypical dermoscopic starburst pattern, appearing below the age of puberty, can be managed conservatively and can be regularly followed up as there is a well-documented tendency of involution.

- •

Atypical Spitz tumors and rare childhood melanomas commonly present as rapidly growing, pigmented or nonpigmented nodules. Immediate excision of any lesion showing these clinical characteristics is indicated.

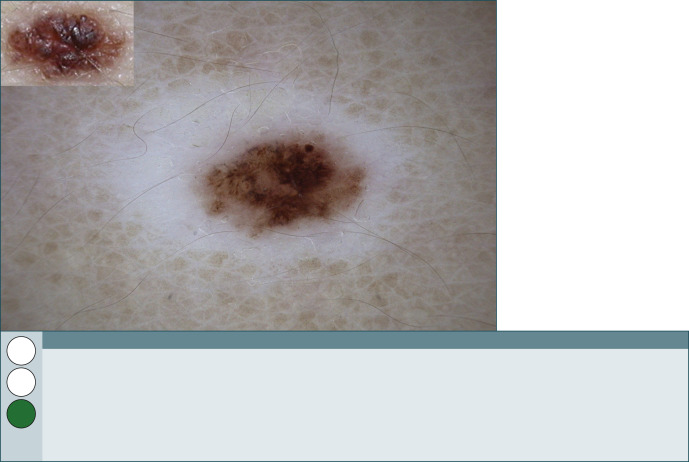

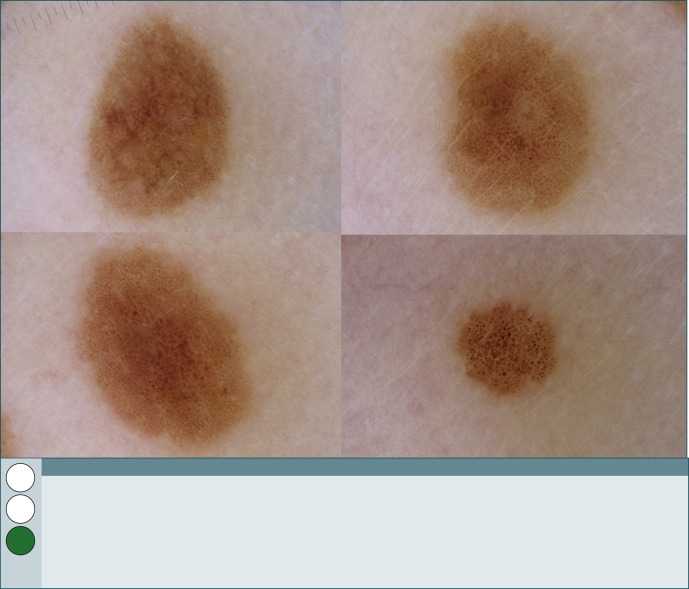

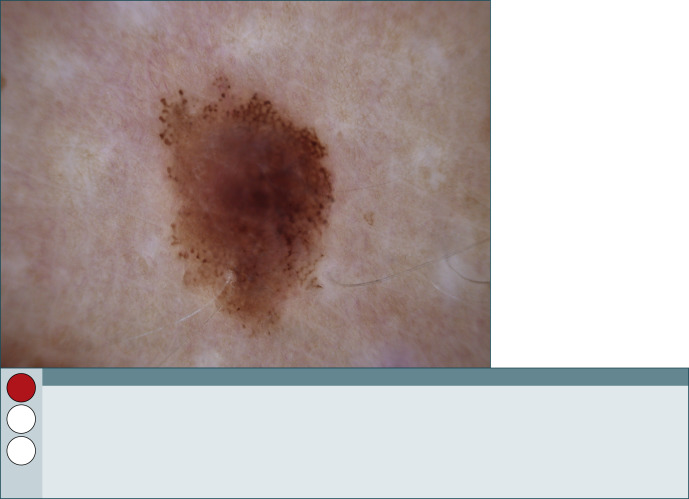

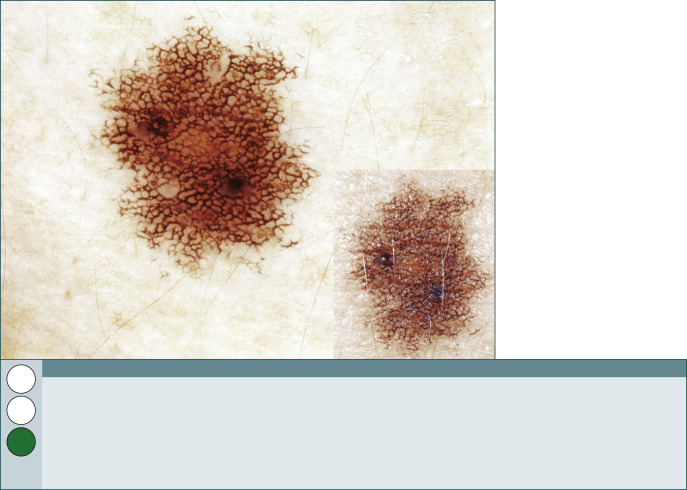

Fig. 261

Congenital nevus.

This congenital nevus revealing some irregularity of color and structure is located on the forearm of a 3-year-old child. Closer scrutiny of the central area displays large and somewhat angulated brown-gray globules (also called cobblestone pattern), which are surrounded by smaller brown globules; characteristic is also the presence of numerous terminal hairs showing either a perifollicular hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Despite the worrisome aspect of this lesion, we raise with confidence the green flag and recommend annual follow-up.

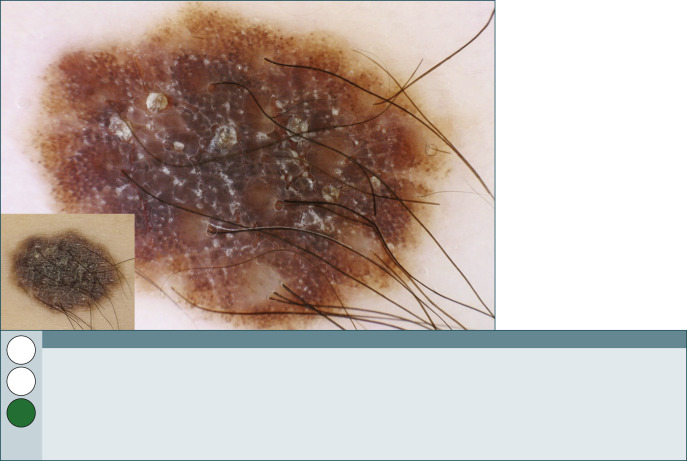

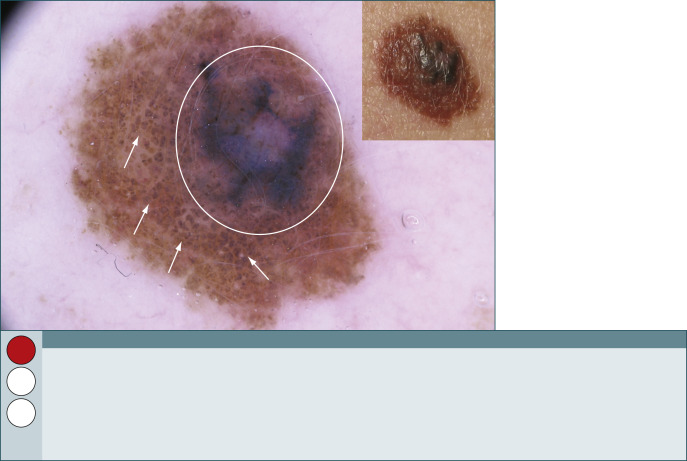

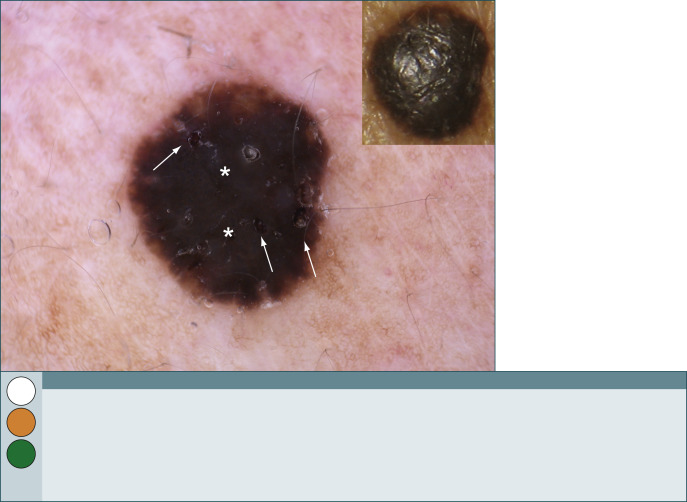

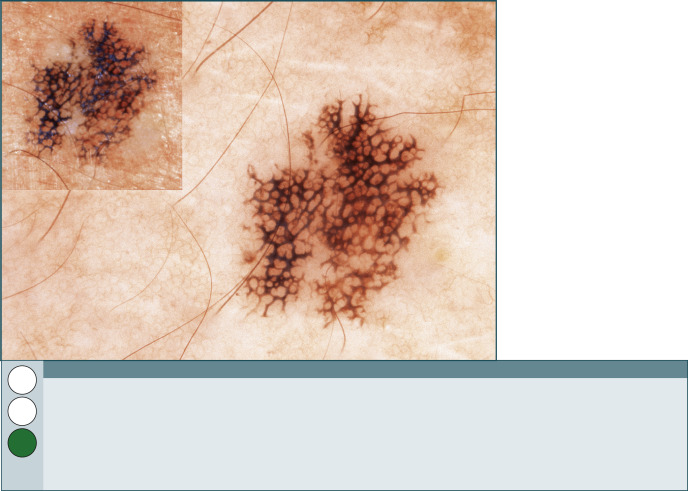

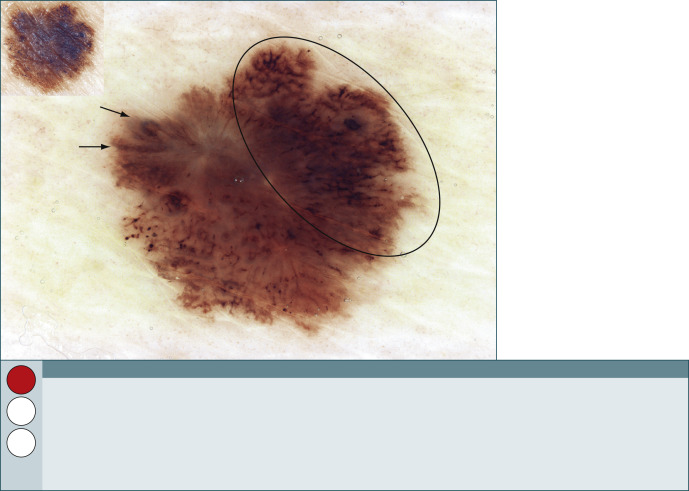

Fig. 262

Melanoma in situ arising in a small congenital nevus.

While melanoma before puberty is very uncommon, the risk increases after puberty. This lesion is located on the shoulder of a 15-year-old girl, who noticed a recent change of color in the preexisting nevus characterized by numerous brown-gray globules resembling cobblestones ( arrows ). Dermoscopically, the melanoma appears as an irregular blue-gray blotch ( circle ) in paracentral location of an otherwise regularly pigmented globular (cobblestone) nevus.

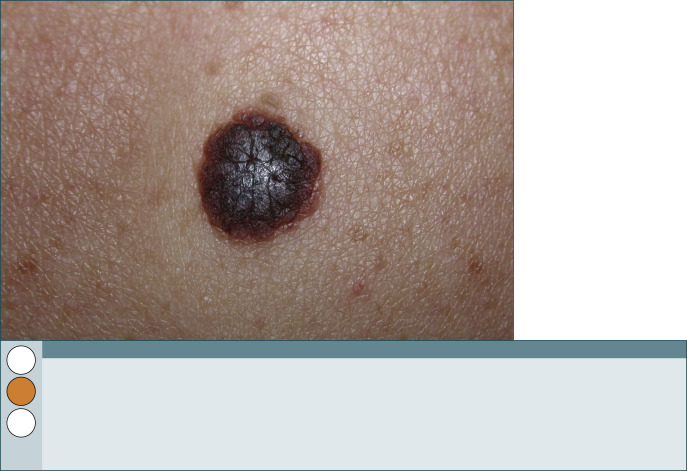

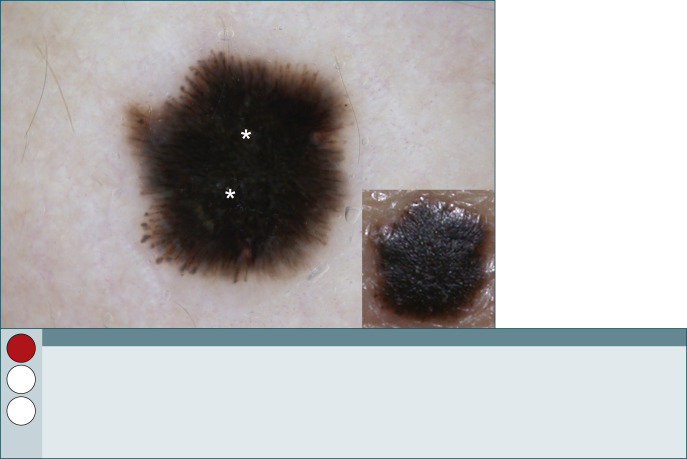

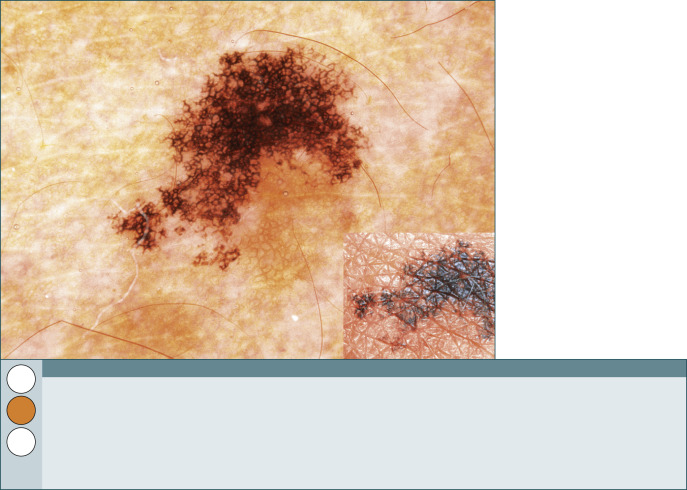

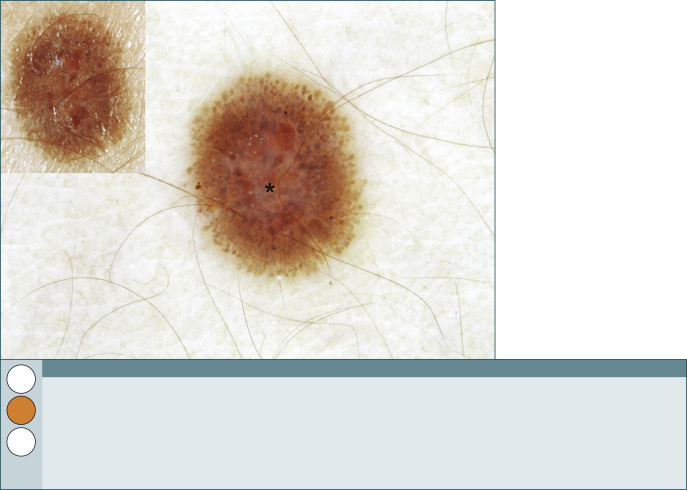

Fig. 263

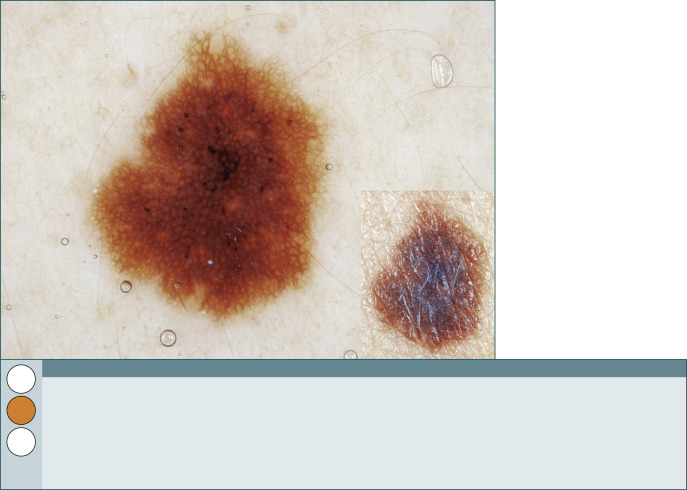

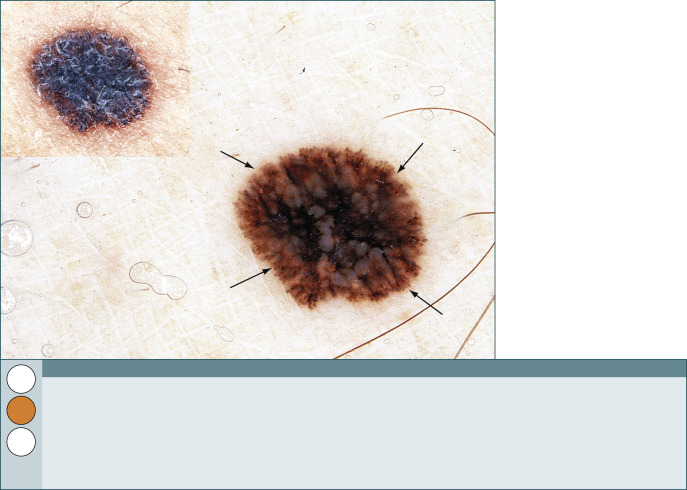

Pigmented Spitz nevus (Reed nevus).

This is a stereotypical example of a flat pigmented Spitz nevus located on the shoulder of a 5-year-old girl. The dermoscopic hallmarks of a pigmented Spitz nevus (commonly also called Reed nevus) are regularly distributed peripheral streaks and pseudopods that arise from a heavily pigmented area, along with a depigmentation in the center of the lesion. During follow-up, these nevi enlarge symmetrically until the disappearance of peripheral streaks indicates stabilization of growth. At this stage, the nevus reveals a homogeneous black-bluish dark brown to black pigmentation. The management decision here, excision versus monitoring, is influenced by the parent’s level of concern and is best decided jointly. We are raising here the orange flag appreciating that the management of these lesions is complex.

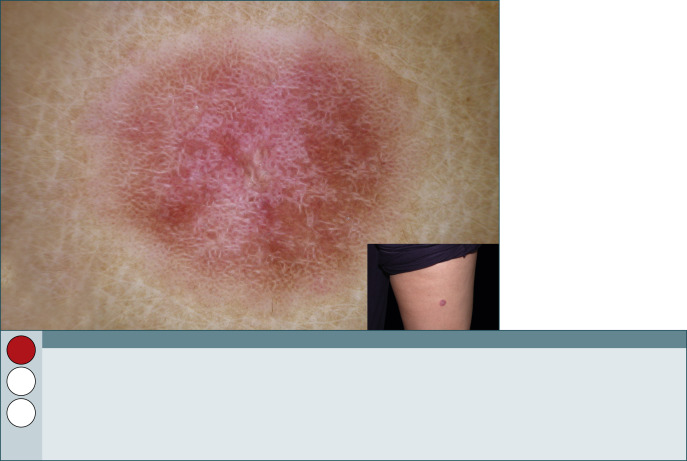

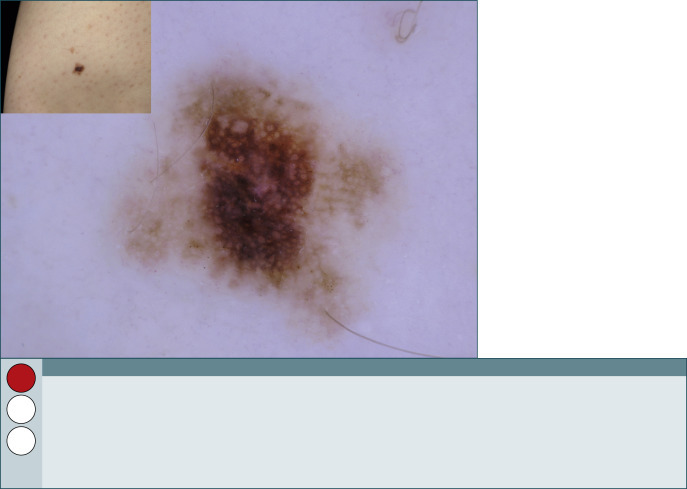

Fig. 264

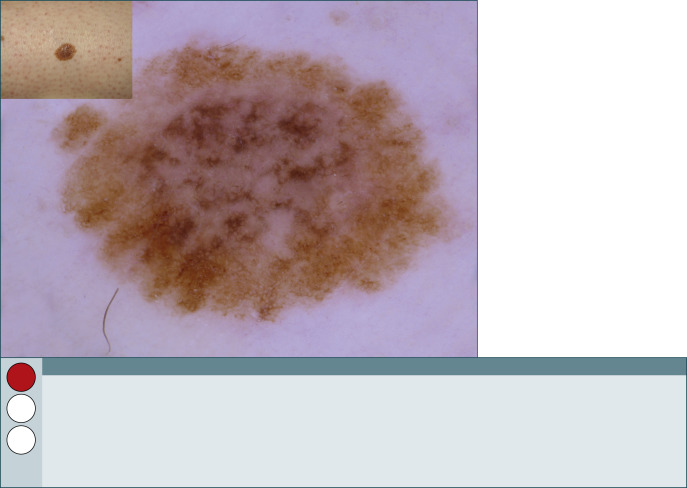

Flat nonpigmented Spitz nevus.

This flat or plaque-like reddish nevus is located on the thigh of a 10-year-old boy. Dermoscopically, nonpigmented Spitz nevi display regularly distributed dotted vessels over a milky-red background as evidenced by this image. Typically a reticular depigmentation can be seen appearing as white net-like lines between the dotted vessels. Because of the lack of both general guidelines and well-documented cases of involution, nonpigmented Spitz nevi should be excised even in children. Remember our slogan, “pink lesion beware,” and raise the red flag.

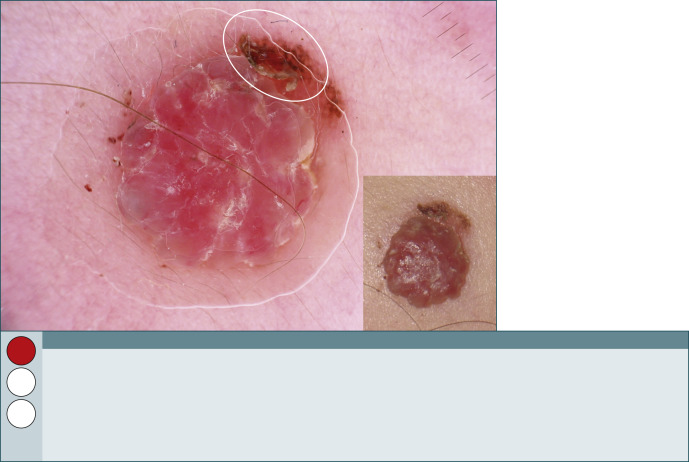

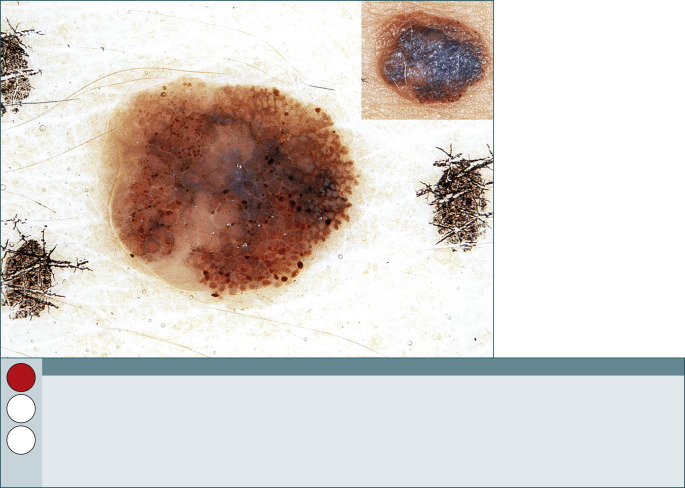

Fig. 265

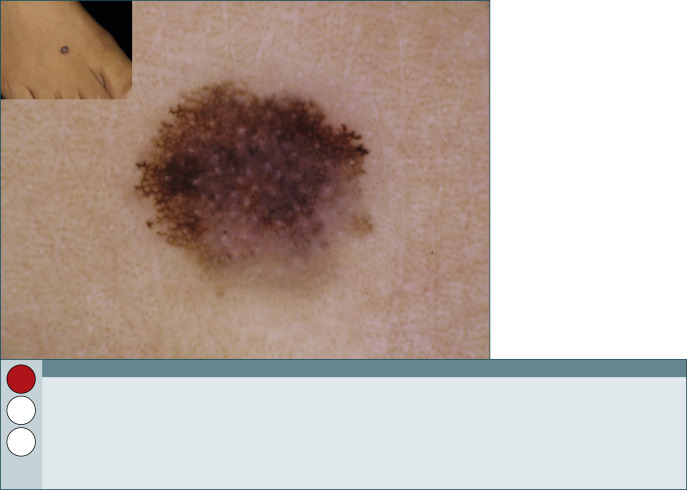

Atypical nonpigmented Spitz tumor.

This reddish nodule was located on the cheek of an 11-year-old girl and revealed a history of rapid growth within a few months. Despite a brown residual pseudonetwork ( circle ), the nonpigmented nodule lacks any specific pattern and exhibits only pink to red homogeneous areas. No doubt we have to raise the red flag here. The lesion was excised and revealed also histopathologically highly conflicting features. The final histopathologic diagnosis was atypical Spitz tumor, and follow-up after 3 years revealed no recurrence.

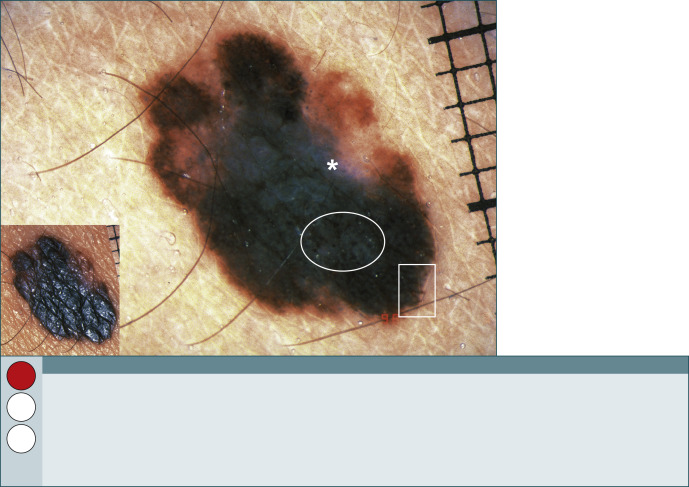

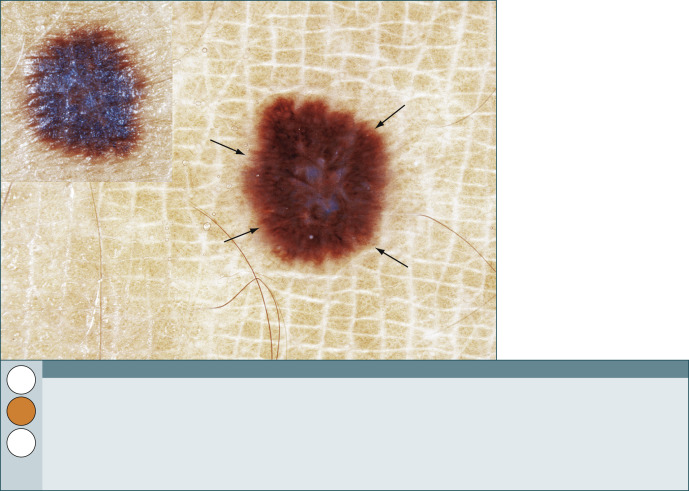

Fig. 266

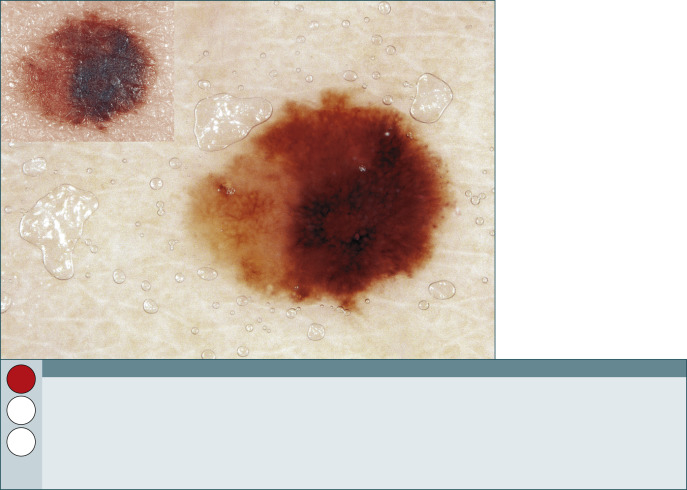

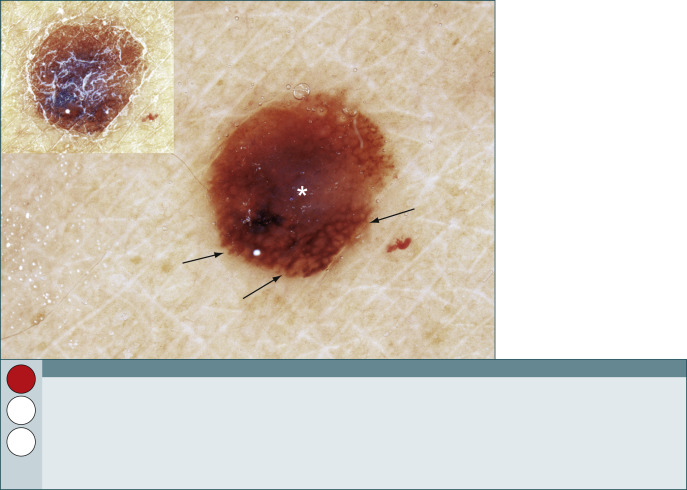

Melanoma.

This is a melanoma on a 14-year-old child. It has melanoma-specific criteria—a blue-white structure ( asterisk ), which is easy to see; subtle streaks ( square ); and irregular dots and globules ( circle ). Young patients do get melanoma and die from their disease, so it is necessary to increase one’s index of suspicion for pediatric patients.

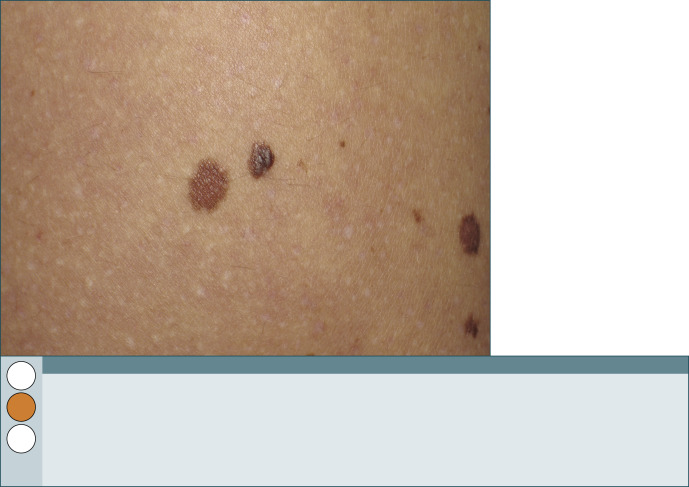

Fig. 267

Common nevi.

This 7-year-old boy reveals some nevi on his back. All nevi are characterized by a uniform pigmentation and by a globular pattern. These nevi do not require any special further attention, and we are raising the green flag with confidence here.

Black lesions

General principles

- •

Clinically, black color is not always ominous.

- •

Black color with dermoscopy is also not always ominous.

- •

The differential diagnosis of a single black macule or papule could be melanocytic or nonmelanocytic, benign or malignant.

- •

What should be done on finding a black lesion? Check it out with dermoscopy before making another move.

Fig. 268

Fig. 269

What is your clinical diagnosis?

This clinically nonspecific dark brown to black lesion ( right ) looks somewhat lighter than the example in Fig. 268 but clearly darker than another lesion ( left ) close by. There is no way to know for sure which is benign and which is malignant. What should be done? Cut it out or check it out? (See Fig. 271 .)

Fig. 270

Melanoma.

This is the dermoscopic image of the lesion in Fig. 268 . Step 1—is it melanocytic or nonmelanocytic? It is a melanocytic lesion because there are brown to black globules in the peripheral zone. Step 2—is it benign or malignant? Can melanoma-specific criteria be identified? The large central blue-white structure, shiny white streaks, and some irregular black globules are enough to warrant excision as soon as possible.

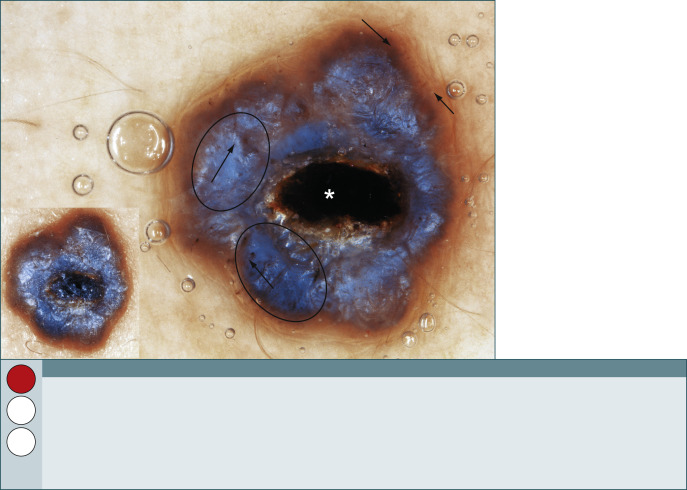

Fig. 271

Melanoma.

This is the dermoscopic image of the lesion in Fig. 269 . Surprise! It’s also a melanoma. It has three melanoma-specific criteria: an atypical pigment network with thickened and smudged lines at 12–2 o’clock, irregular globules at the periphery from 8‒12 o’clock, and a subtle blue-white structure in the upper pole of the lesion.

Fig. 272

Seborrheic keratosis.

Is there a blue-white structure ( asterisks ) here? Maybe there are some subtle streaks at the periphery of the lesion. And there might be a few comedo-like openings ( arrows ). So, this lesion has melanoma-specific criteria and criteria seen in a seborrheic keratosis. Sometimes an acanthotic seborrheic keratosis may be heavily pigmented and nearly devoid of any typical criteria. In a case like this, the expert raises the green flag and the beginner might be more cautious and raise the orange flag and excise the lesion. Remember, if in doubt, cut or shave it out.

Fig. 273

Spitz nevus.

The differential diagnosis for this Spitzoid appearance should include pigmented Spitz nevus (also called Reed nevus) and melanoma. There is a central rather subtle blue-white structure ( asterisks ) and symmetrically oriented streaks around the lesion. These features favor the diagnosis of a Spitz (Reed) nevus. If a lesion like this one is found in a patient after puberty, a diagnostic excision needs to be performed. Because this lesion was located on the dorsal hand of an adult woman and, in addition, there was also a history of rapid growth, this lesion was excised.

Inkspot lentigo

General principles

- •

Clinically and dermoscopically inkspot (or reticular) lentigines have a very characteristic appearance.

- •

Typically, an inkspot lentigo is black and sharply demarcated with a bizarre-looking pigment network filling the lesion. There is an absence of other criteria.

- •

Individuals with inkspot lentigines commonly have fair skin, light hair, and light eyes and are at risk of developing melanoma. Do not forget to do a comprehensive skin examination to look for high-risk pigmented skin lesions.

- •

Inkspot lentigines are usually located on the upper trunk and extremities and are surrounded by regular or large sunburn freckles.

- •

On seeing an “inkspot lentigo,” try not to miss seeing the presence of any melanoma-specific criteria.

- •

If in doubt, cut or shave it out.

Fig. 274

Inkspot lentigo.

This is a variation of the morphology seen in an inkspot lentigo characterized by a bizarre pigment network. There is also a large homogeneous area with a gray color representing melanophages in the papillary dermis.

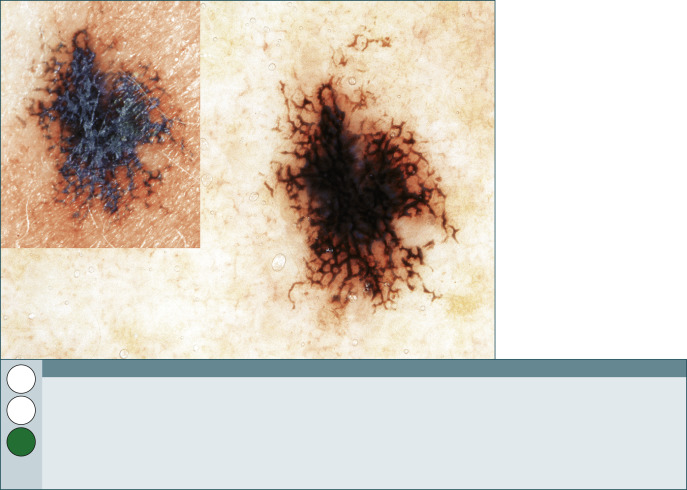

Fig. 275

Inkspot lentigo.

This is a stereotypical inkspot lentigo. The network is commonly black.

Fig. 276

Inkspot lentigo.

A third variation of the appearance of inkspot lentigo. The clinical appearance, dark color, bizarre shape of the pigment network, and absence of other criteria suggest the correct diagnosis.

Fig. 277

Inkspot lentigo.

This picture is worrisome because of the asymmetry of color and structure, the irregular dots and globules, and the irregular blotch. It is not wrong to biopsy a lesion that looks like this.

Fig. 278

Clark (dysplastic) nevus.

The quality of the pigment network is suggestive of a reticular type of Clark (dysplastic) nevus. The pigment network is atypical, with variation in line thickness, and the color is blotchy. Therefore, excision or short-term digital follow-up (in the literature commonly referred to as sequential digital dermoscopy imaging or SDDI) is recommended. When the lesion is excised, the final histopathologic diagnosis depends on the judgment of the pathologist, and may range from slight to moderate to severe atypia.

Fig. 279

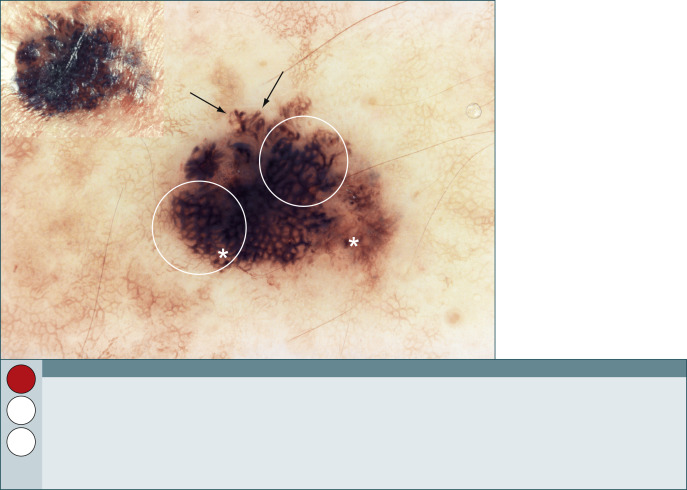

Melanoma.

This lesion is black with a pigment network, but these are the only features this melanoma has in common with an inkspot lentigo. This lesion has prominent melanoma-specific criteria—an atypical pigment network ( circles ), irregular dots and globules ( asterisks ), and rather typical streaks ( arrows ).

Blue lesions

General principles

- •

Blue color can be seen in benign and malignant lesions. They are not all blue nevi.

- •

Blue color indicates that melanin is deep in the dermis.

- •

It is imperative to develop a complete differential diagnosis for blue lesions.

- •

If you see a lesion with blue color but it also has other criteria, it should be evaluated like any other lesion.

- •

Blue lesions can be tricky. If in doubt, do not hesitate—cut it out.

Fig. 280

Nodular melanoma on the face.

This rather expophytic, ulcerated, and hemorrhagic tumor shows structureless blue-white color in the absence of any specific criteria of a melanocytic or nonmelanocytic tumor. Although structureless blue color may be seen also in blue nevi, the irregular distribution of colors together with the ulceration and bleeding represents a high-risk dermoscopic image and must be removed. In fact, it turned out to be a nodular melanoma.

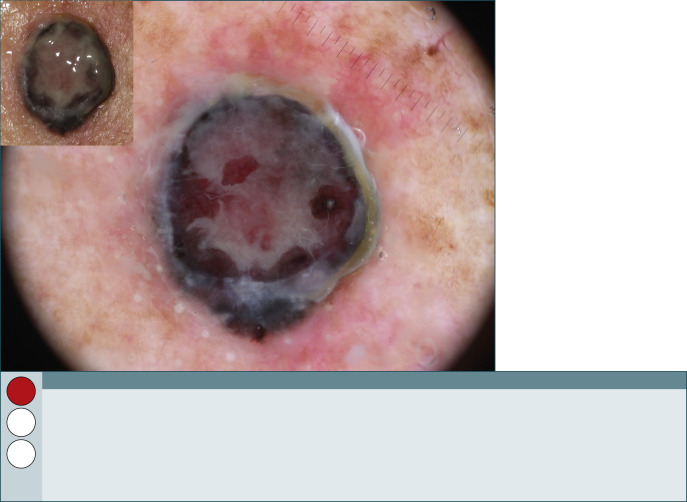

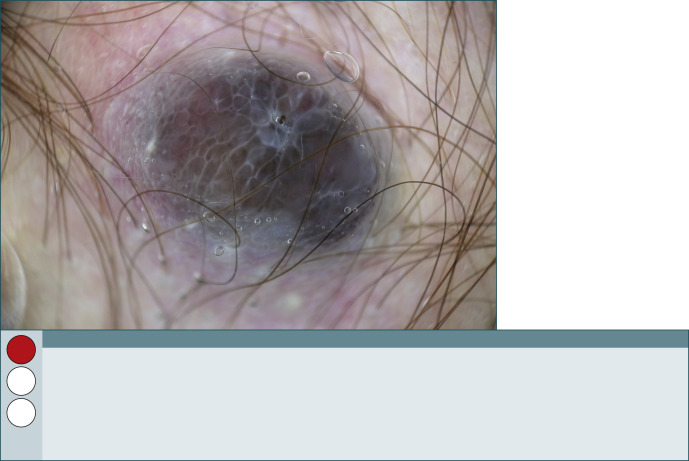

Fig. 281

Basal cell carcinoma.

Another example of a blue-whitish ulcerated nodule prompting us to immediately raise the red flag. There are evident focused vessels and some isolated gray globules as well as a large central ulceration. The experienced dermoscopist might favor a basal cell carcinoma but will insist on a diagnostic excision with high priority because a nodular melanoma cannot be ruled out with certainty.

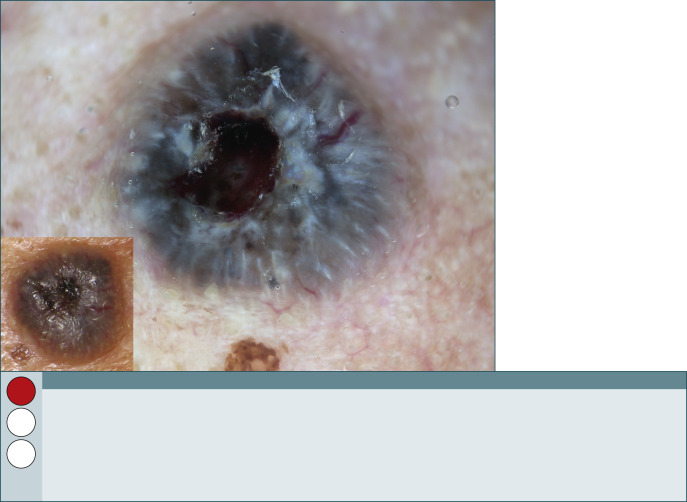

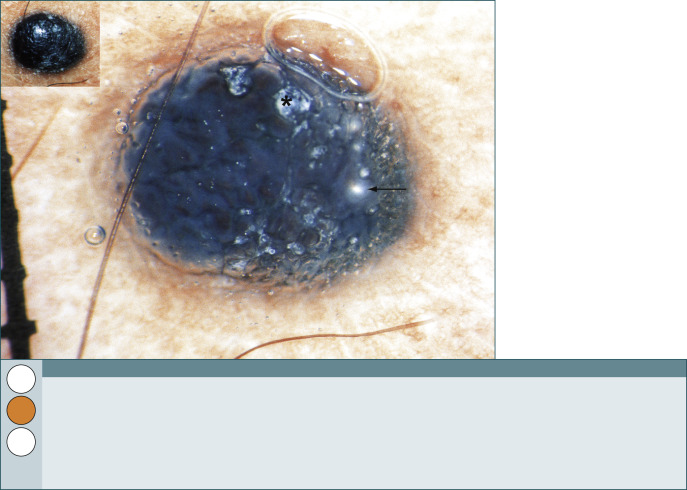

Fig. 282

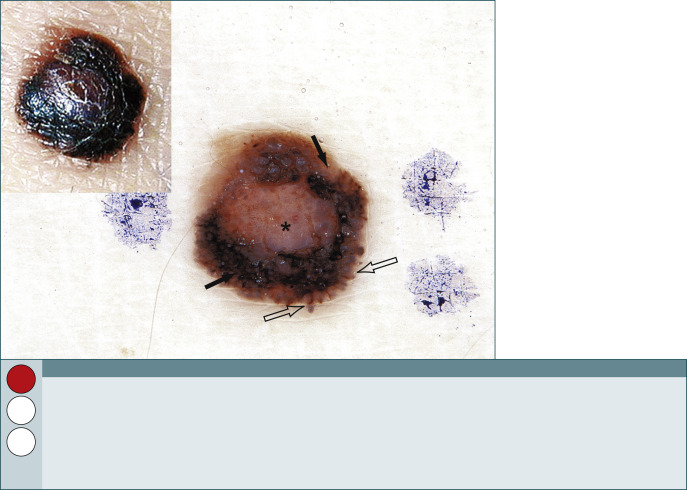

Melanoma.

One’s first opinion might be that this is a basal cell carcinoma because of the ulceration ( asterisk ) and vessels ( white arrows ). Scan the lesion for all criteria. It actually has dots and globules ( circle ), so it is melanocytic. Now it is looking like a melanoma because of the blue-white structure, asymmetrically located irregular dots and globules, and irregular streaks ( black arrow ). This lesion therefore needs a diagnostic excision with a high-level of priority. The dermoscopic picture will help in planning the surgical approach. It is important not to shave through this invasive melanoma.

Fig. 283

Basal cell carcinoma.

This lesion is remarkably similar to that shown in Fig. 282 . Features include ulceration ( asterisk ), blue-white structures ( circles ), and a few irregular dots and globules ( arrows ). This lesion is melanocytic by definition if the rules are strictly followed, although it turned out to be a basal cell carcinoma. The important point is that this dermoscopic picture needs a diagnostic excision with a high-level of priority.

Fig. 284

Melanoma metastasis.

The differential diagnosis of this bluish nodule in the axilla is a blue nevus on one hand and a nodular melanoma or a melanoma metastasis on the other. No doubt the history of the given tumor is of high importance; blue nevi usually have a very stable history in contrast to melanoma or melanoma metastasis, which grow rapidly. In this case, the nodule developed rapidly in a patient with a previous primary melanoma. This along with the dermoscopic aspect should always lead to biopsy—here it was a melanoma metastasis.

Fig. 285

Blue nevus.

This is a good example of a blue nevus with relatively homogeneous blue color. It is dry and scaly ( asterisk ) with milia-like cysts ( arrow ). Do not forget that the differential diagnosis includes nodular and cutaneous metastatic melanoma. The entire clinical picture will help one decide on the management of this lesion.

Reticular lesions

General principles

- •

Take a bird’s-eye (global) view of the entire lesion to get a first impression.

- •

Reticular pattern = significant areas with pigment network.

- •

Is the pigment network typical or atypical?

- •

What other criteria are there to make the dermoscopic diagnosis?

Fig. 286

Melanoma in situ.

Surprisingly this turned out to be an in situ melanoma. It does not look that worrisome. There is enough pigment network to say it has a reticular pattern, and the pigment network is slightly atypical. The subtle irregular streaks ( circle ) push this lesion over the edge to be malignant. Statistically, a lesion with this dermoscopic picture would not be a melanoma but a Clark (dysplastic) nevus. It is suspicious enough to warrant a histopathologic diagnosis.

Fig. 287

Clark (dysplastic) nevus.

The pigment network fills most of this lesion. It has more of a reticular pattern than that shown in Fig. 286 . The pigment network and dots and globules are questionably atypical but not strikingly worrisome. Differentiate this benign nevus from the in situ melanoma in Fig. 286 . Here the network lines are thin and fade out at the periphery, in contrast to the previous case.

Fig. 288

Clark (dysplastic) nevus.

The pigment network is slightly atypical in this lesion because the line segments are thicker, branched, broken up, and vary in color. The central area of hypopigmentation is reminiscent of blue-white structures, and in combination with the slightly atypical pigment network we cannot rule out a superficial melanoma. We excised this lesion, and our pathologist reported it as a Clark (dysplastic) nevus with severe atypia; however, we are well aware that other pathologists would report this lesion as a melanoma.

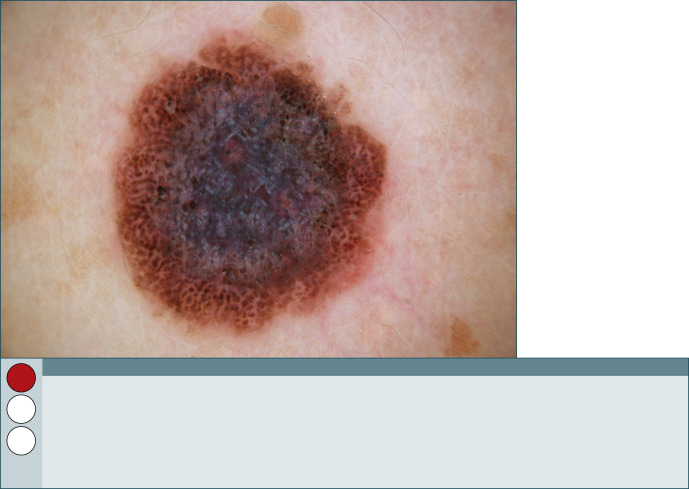

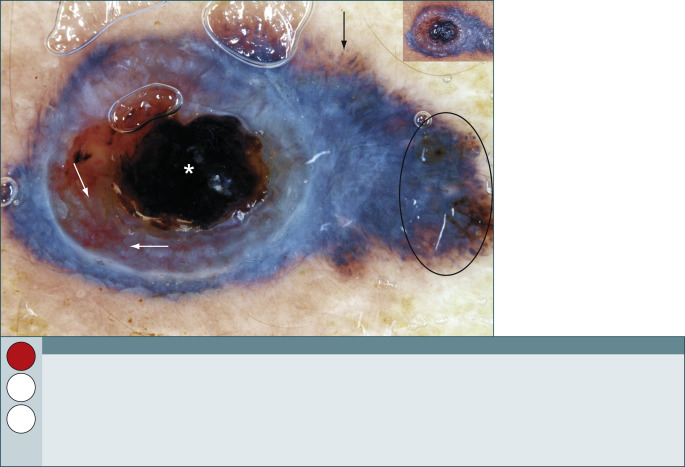

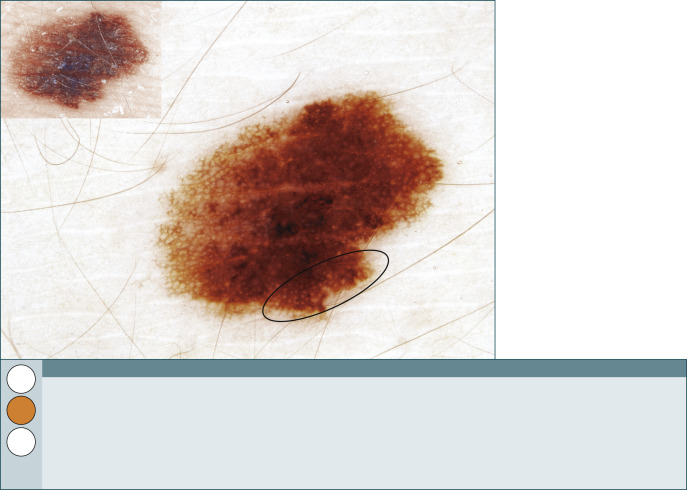

Fig. 289

Melanoma.

This lesion looks more ominous with a reticular pattern forming a simulant of a starburst pattern. There are branched streaks along the periphery from 8‒2 o’clock. This favors the diagnosis of a melanoma. This diagnosis is supported by the blue-white structures in the center and lower right of the lesion. A further melanoma-specific criterion is the presence of subtle irregular dots and globules at the center of the lesion. Excise this lesion.

Fig. 290

Melanoma.

Imagination is needed to recognize the streaks and atypical pigment network that classify this as a reticular pattern. The dermoscopist should realize that this is a high-risk lesion because of the clear-cut asymmetry of color and structure. As is the case here, an early in situ melanoma may be hard to diagnose.

Fig. 291

Melanoma.

This bizarre dermoscopic picture shows areas with very atypical pigment network ( circle ), irregular streaks ( arrows ), and irregular dots and globules in the left lower part of this lesion. Never tell a patient that they definitely have a melanoma based on the dermoscopic picture, no matter how ominous it looks. The result of the histopathologic examination sometimes may surprise you.

Spitzoid lesions

General principles

- •

Spitzoid means similar in appearance to a starburst pattern.

- •

Spitzoid differential diagnosis includes Clark (dysplastic) nevus, Spitz nevus, and melanoma.

- •

Spitzoid morphology comprises a light-dark or blue central area and dots and globules or streaks at the periphery.

- •

Symmetrical Spitzoid pattern = benign lesion.

- •

Asymmetrical Spitzoid pattern = rule out melanoma.

- •

The stereotypical starburst pattern is seen more frequently than the globular pattern, which is more common than the nonspecific Spitzoid pattern.

Caution

Deaths have occurred secondary to metastatic “Spitz” nevi that were in reality melanomas. Excise the vast majority of Spitzoid lesions. It is better to be safe than sorry.

Special nevi

General principles

- •

Special nevi are defined as benign melanocytic nevi that exhibit a rather specific constellation of features resulting often in a targetoid or iris-like appearance.

- •

The group of nevi with special features includes Sutton nevi, Meyerson nevi, traumatized nevi, recurrent nevi, combined nevi, and cockade nevi.

- •

Special nevi can be clinically easily diagnosed, and in most cases, dermoscopy simply confirms the clinical diagnosis.

- •

A special history of injury or incomplete surgical removal provides further clues for the diagnosis of traumatized and recurrent nevi.

- •

Special rules have been established for the management of special nevi.