Closed Reduction of Zygomatic Arch Fractures

Oluwaseun A. Adetayo

DEFINITION

The zygoma bone has four skeletal articulations—the maxilla, frontal, temporal, and sphenoid bones.

The zygomatic arch plays a prominent role in facial skeletal profile by establishing malar projection (“cheek bones”).

Fractures of the zygomatic arch can occur in isolation. In such cases, the tetrapod articulations are usually not violated and the remainder of the complex is stable.

This chapter focuses on closed reduction and treatment options for isolated zygomatic arch fractures.

ANATOMY

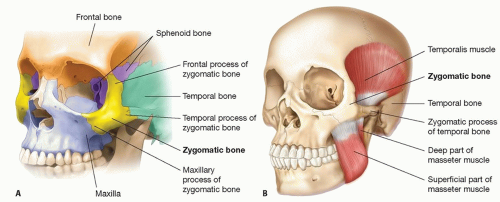

The zygomatic arch is a part of the zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC). The bone and its articulations are shown in (FIG 1A).

Although the term “arch” is used to describe the bone, it is more anatomically flat in configuration for the majority of its length and is curved posteriorly.

The zygoma is also an important landmark for the muscles of mastication.

The zygomatic arch furnishes attachments for portions of the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS), the temporoparietal fascia (TPF), and origins for some of the muscles of facial expression and mastication.

The highly powered masseter muscle has superficial and deep components that take their origin from the zygomatic arch and insert into the buccal surface of the mandibular angle, ramus, and body. Portions of the deep fibers of the muscle also radiate to the anterior capsule and the articular disk of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), thus helping to stabilize the capsule of the TMJ.

FIG 1 • A. The zygoma bone and its articulations. B. The relationship of the masseter and temporalis muscles to the zygomatic arch.

Fractures of the zygomatic arch may disrupt the origin of the masseter and potentially affect elevation and protrusion of the mandible, resulting in pain, trismus, and occlusal problems.

The temporalis muscle is located deep to the zygomatic arch as it inserts onto the coronoid process. Depression of an isolated arch fracture can contribute to trismus or malocclusion, via an indirect impingement on the temporalis.

The relationship of the masseter and temporalis muscles to the zygomatic arch are depicted in FIG 1B.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

All trauma patients should undergo appropriate evaluation to rule out any concomitant facial fractures or other lifethreatening injuries.

Physical findings in patients with zygomatic arch fractures may include facial asymmetry, loss of malar projection, trismus, pain, and decreased maximum incisal opening (MIO).

Trismus and decreased MIO can occur due to direct pull of the masseter on the arch, impingement of a displaced arch on the temporalis muscle as it inserts into the coronoid, or more directly via its compressive effect on other muscles of mastication.

Facial asymmetry may result because of actual displacement of the arch or disruption of the origin of the zygomaticus muscles, which contribute to facial expression.

IMAGING

Various modalities including x-rays, ultrasounds, and computed tomography (CT) scans have been described for evaluation of zygoma fractures.1,2,3

CT scans are the most commonly utilized diagnostic tools in patients with facial fractures and provide excellent detail for the evaluation of zygomatic fractures.

CT scan using fine cuts with axial, coronal, and 3D reconstruction are particularly helpful to evaluate the degree of displacement, impingement, malrotation, and associated fractures.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management of isolated zygomatic arch fractures is the treatment choice in patients with the following:

Nondisplaced or noncomminuted arch fractures

Lack of trismus

Lack of facial or malar asymmetry

Normal MIO

Preservation of facial width and projection

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Operative intervention should be considered in patients who are medically stable with sequelae of arch fractures such as trismus, malar flattening, facial asymmetry, difficulty with mouth opening, and presence of concomitant fractures.

The goals of treatment are:

Anatomic restoration of three-dimensional anatomy of the zygoma with articulation and muscular complexes

Restoration of facial width and malar projection

Resolution of symptoms due to fracture

Restoration of orbital volume and anatomy in cases of orbitozygomatic fractures

Preoperative Planning

A complete history and physical examination should be performed on every patient and all concomitant injuries identified.

Obtain imaging of choice. Most commonly used are craniomaxillofacial CT scans with fine cuts (range of 0.625- to 1.25-mm cuts at most institutions) and includes axial, sagittal, coronal, and 3D imagings as needed.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with exposure of the head and neck to facilitate access. CT scan images are displayed intraoperatively.

Approach

The following approaches have been described for treatment of isolated zygomatic arch fractures:

Percutaneous approach

Gilles approach

Keen approach

Others

TECHNIQUES

▪ Percutaneous Approach

A 0.5- to 1-cm cutaneous incision is made directly overlying the zygoma, and a reduction instrument such as a bone hook or a Carroll-Girard T-bar screw is inserted into the body of the zygoma.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree