CHAPTER 45 Surgical Treatment in China

KEY POINTS

Treatment of lymphedema in China has traditionally been surgical.

Initially excisional operations were done.

Bypass procedures have been performed since the late 1970s.

Beginning in the early 2000s, liposuction, alone or in combination with microsurgery, became popular.

Today very few cases of microlymphatic surgery are performed.

New technologies, such as magnetic resonance lymphangiography, have enhanced surgeons’ ability to identify lymphatic structures and make specific diagnoses and help to guide appropriate treatment strategies.

This chapter is a historical look at how Chinese surgeons have treated lymphedema over the past six decades. There is no detailed description of how these specific operations are performed. This review discusses both the successes and failures of various treatment approaches and examines the prospects for further improvements in the future.

Lymphatic filariasis was the main cause of secondary lymphedema in China in the early 1950s. More than 20 million individuals were affected by filariasis, of which more than 5 million cases of lymphedema were caused by filariasis. 1 The disease was predominantly found in agricultural villages, where most inhabitants were unable to receive timely treatment for the disease. In addition, inadequate treatment capabilities in these rural locations meant that by the time most patients, were diagnosed, they were already well into the advanced stages of the disease. At that time, the primary treatment method for lymphedema was surgical, and the Charles and Thompson procedures were commonly performed because elephantiasis was widespread.

Because of the excision of large amounts of hyperplastic tissue, drastic reduction in bulk could be seen at the surgical sites, making the surgical results readily apparent. This is especially true for the Charles procedure, a method advocated by most surgeons at the time. In addition, to treat erysipelas, the village doctors in Fujian Province invented an “oven” made from bricks. The affected limbs were inserted into the oven and heated repeatedly, thereby significantly decreasing the rate of infection and to some extent the swelling. This method later developed into the socalled heating and bandage treatment. 2 At the same time, there were scattered reports of only one or two documented cases of treatment involving transposition of the pedicle or free transplantation of the omentum to the axillary or inguinal region for draining lymphedema of the arm and leg. 3 However, long-term follow-up showed no obvious effect on reducing lymphedema.

During the 1970s, microscopic surgery for lymphedema treatment began to develop in China. In 1977 Dr. Di Sheng Chang 4 was the first to present 11 cases of lymphaticovenous anastomosis. Of these 11, only 2 had good outcomes in the early stages. By early 1981, there were 60 cases reported from six surgical centers around the country. In 1988 more than 800 cases of lymphaticovenous anastomosis were reported worldwide. Among them, Chinese surgeons reported 300 such cases; lymphatic microsurgery had become very popular among the national surgeons. However, strict regulations were not enforced for case selection for lymphaticovenous anastomosis. Thus this surgery was performed for almost all stages of this disease, whether early, late, or primary or secondary. To create more anastomoses, three to four incisions were made in the affected limb, in which two to four lymphaticovenous anastomoses were applied at each surgical site. The reported clinical outcome of these microsurgical treatments on the lymphatic system was based solely on physical signs; the patency rate of lymphaticovenous shunting was not objectively proved in most reports.

In the 1990s new and innovative procedures emerged for the surgical treatment of lymphedema, including the anastomosis of superficial and deep lymph vessels. Wei Gang Cao et al 5 reported 8 successful cases of 13, whereas in the remaining 5 patients the surgeries were unsuccessful because the collecting lymph vessels (superficial or deep) were not found, which underscored the difficulties associated with the procedure. Several centers reported that anastomosis of the external iliac lymph vessels with the inferior epigastric vein was effective in alleviating chylous ascites. 6 Based on a decade of clinical observations, surgeons reached an agreement:

Microlymphatic surgeries have a better clinical outcome for secondary lymphedema than for primary lymphedema.

Patients with secondary lymphedema for 5 years or less showed better treatment outcomes than patients who had the disease for more than 5 years.

Microlymphatic surgeries reduce the number of episodes of erysipelas.

For advanced cases of lymphedema, the Charles procedure was still preferred.

After 2000, there was a decrease in the number of reported cases of lymphaticovenous microlymphatic surgeries. During this period, liposuction developed as a new treatment method for lymphedema of the extremity. It was used as a stand-alone operation for an entire limb or in combination with microsurgery. 7 When combined with microsurgery, liposuction was performed at the distal part of the limb (lower leg or forearm), whereas free flap transplantation or lymphaticovenous anastomosis was done at the inguinal or axillary region. 8

To treat secondary arm lymphedema after radical mastectomy, flaps such as the latissimus dorsi and free abdominal flap transplantation to the axillary region were carried out at a few centers. Postoperative lymphoscintigraphic findings showed a decrease in dermal backflow in the affected limb. 9 An alternative treatment method for breast cancer–related lymphedema of the arm was the transplantation of the great saphenous vein to bridge the deep and superficial lymphatic vessels. 10 Five of nine patients showed an initial reduction of arm swelling.

Xiaoxia Li et al 11 were the first to describe the use of autotransplantation of bone marrow stem cells to treat lymphedema. Although the authors believed that bone marrow–derived stem cells have an effect on reducing lymphedema, there was no objective evidence (such as lymphatic system imaging) of regeneration or repair of lymphatic vessels in the treated limbs.

An increasing number of patients who underwent the Charles procedure during the 1950s to 1990s returned to the hospital for treatment of their surgical complications, which included chronic ulcer, lymphorrhea, and disability of the ankle resulting from hypertrophic or atrophic scar. The lower legs that received split-skin grafts were often much smaller than the thighs. In addition to the affected external appearance, the surgical sites in some patients developed malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma or angiosarcoma. Unfortunately, the lack of viable alternatives meant that the Charles procedure was still the primary approach for many surgeons when patients reached the advanced stages.

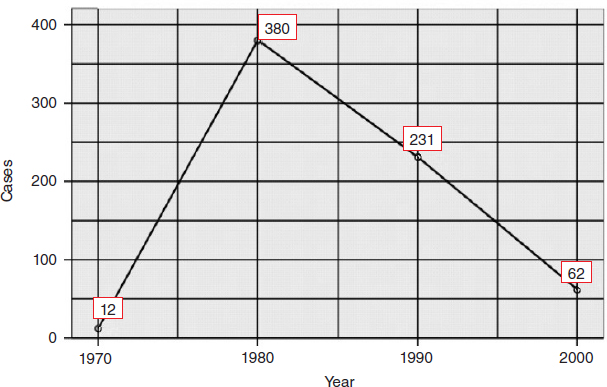

Since 2010, the number of reported microlymphatic surgeries has been dramatically reduced compared with the 1970s and 1980s (Fig. 45-1). At this writing, no more than three medical centers in China are routinely performing microlymphatic surgeries for the treatment of lymphedema. The Department of Plastic Surgery at the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital and the Beijing Plastic Surgery Hospital are attempting to treat arm lymphedema resulting from breast cancer treatments with vascularized lymph node transplantation or combining with free flaps to perform breast reconstructive surgery at the same time. 12 Nevertheless, the number of reported cases still remains in single digits. Furthermore, the long-term effects of the procedures are still under evaluation. The Department of Lymphatic Surgery at Beijing Shijitan Hospital has carried out thoracic duct surgery for more than 20 years to treat visceral lymphatic deformities, such as chylous reflux lymphatic malformations and chyloperitoneum. They have accumulated much experience in the field of thoracic duct surgery. Lymphaticovenous anastomoses combined with liposuction are also regularly performed to treat lymphedema of the extremity.

In the history of surgical treatment of lymphedema in China, microlymphatic surgery was once the high-flying treatment in the 1970s to 1990s, followed by debulking procedures. Chinese surgeons may have performed the most of this type of procedure in the world. However, in recent years, progressively fewer surgeons have attempted these procedures, resulting in a net decrease in surgical case reports. The primary reason is low patient satisfaction with the outcome. The lack of knowledge regarding lymphatic disease and the limited capabilities of imaging technology meant that many microsurgical treatments for lymphedema were performed with a certain blindness. The surgeons may not have been completely clear about the morphologic and functional status of the lymphatic system in the lymphedematous limbs (for example, secondary lymphedema resulting from malignant tumor surgeries) before the lymphatic surgery. It is possible that the vessels were already partially obstructed or functionally impaired, resulting in an anastomosis that was bound to fail. Again, there was a lack of information on the type or subtype of primary lymphedema, such as pathologic changes in the lymph vessels or a combination of both lymphatic and lymph nodal disease. A surgical approach to reconstruct lymphatic pathways on a severely deformed system is impossible. The indications for microlymphatic surgery should not be based solely on the stage (early or late) of the disease.

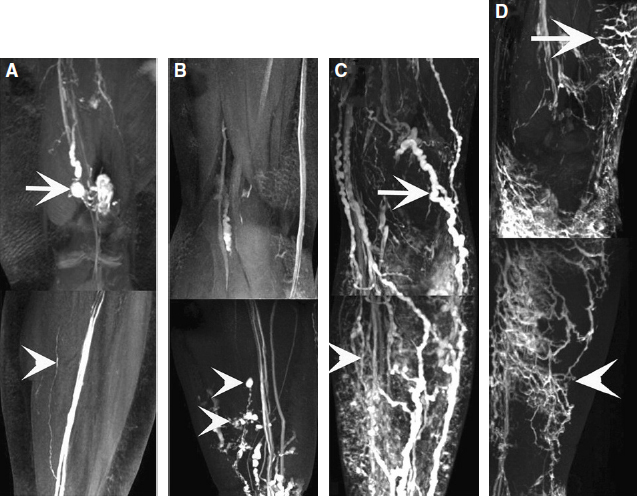

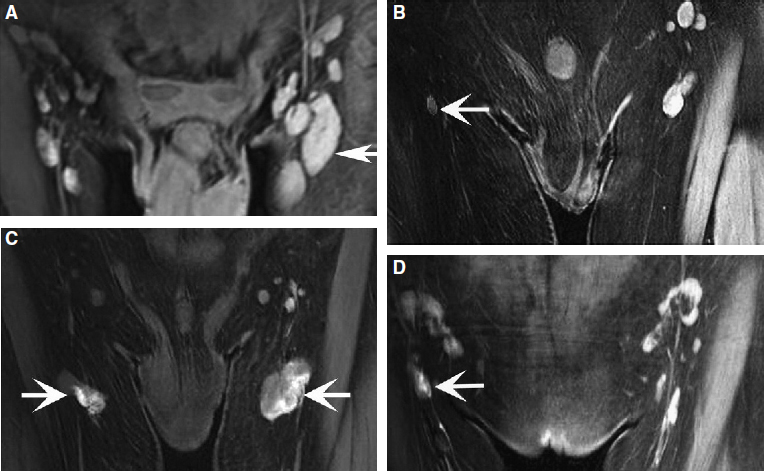

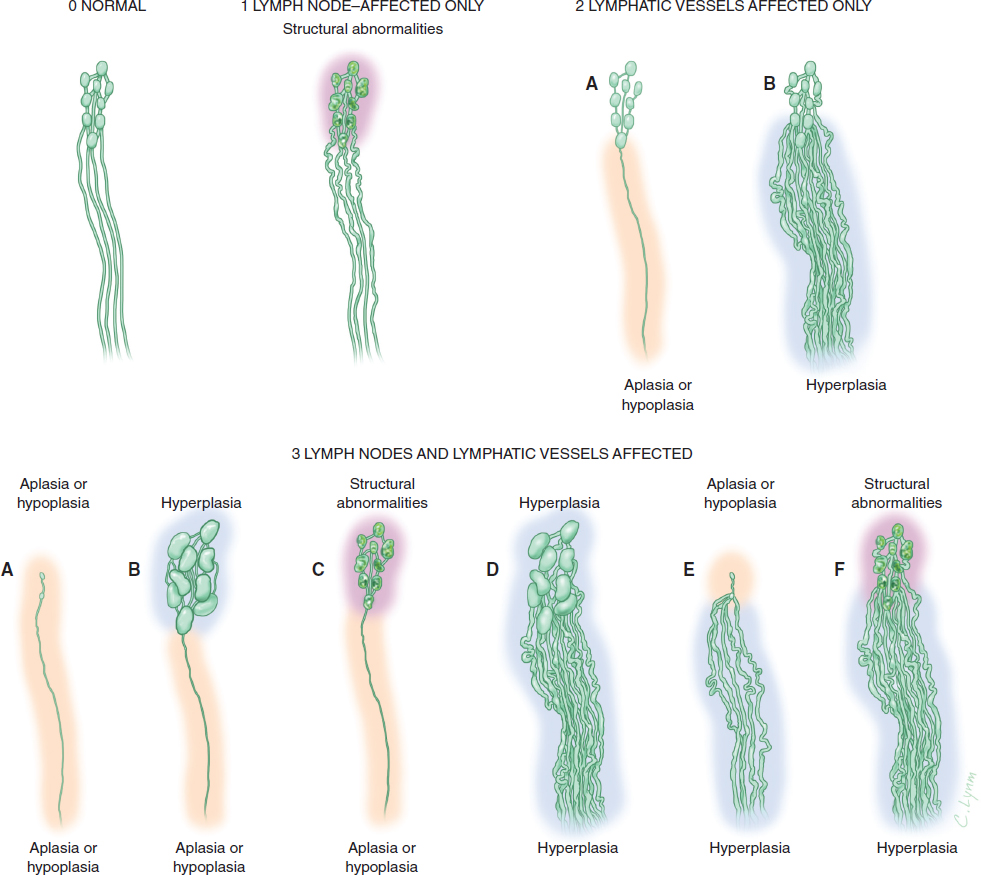

In recent years, medical imaging of the lymphatic system has advanced rapidly. The diagnostic value of new technologies, such as magnetic resonance lymphangiography (MRL), for evaluating the lymphatic system and the stage of disease has increased exponentially. 13 , 14 High-resolution imaging and real-time observation of the structures and functional anomalies of the lymphatics and lymph nodes can help surgeons make a more precise diagnosis (Figs. 45-2 and 45-3) and accurately identify the type or subtypes of lymphatic pathologies (Fig. 45-4).

Based on the more comprehensive evaluation of a patient’s lymphatic system that is made possible by MRL, appropriate surgery can then be selected, treatment can be much better individualized, and an improved curative effect can be expected. By the same token, the previous lack of high-resolution imaging also meant a lack of reliable tests to objectively evaluate the patency of lympha ticovenous anastomoses or lymphatic regeneration after free lymph node transfers. Sometimes it was difficult to determine whether the decrease in patient bulk was from restoration of the lympha tic circulation or from bandaging and bed rest in the hospital after surgery. The three-dimensional dynamic MRL may help provide an objective measure of clinical outcome and prognosis.

The Present and the Future

Currently surgery is no longer the major treatment for lymphedema. Instead, the trend has shifted toward more conservative methods, such as comprehensive decongestive therapy, to reduce edema and remodel the shape of an enlarged limb. Are surgeries no longer necessary for the treatment of lymphedema? The answer is certainly that surgery must remain an option. As long as the lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels are clearly identifiable and accessible, surgery should never be ruled out as a possible treatment choice.

With further advancements in medical technology and as our knowledge of the lymphatic circulation system and pathologic mechanisms of lymphatic disorders increases, Chinese surgeons will strive toward the goal of discovering successful innovations in surgical procedures for the treatment of lymphedema.

CLINICAL PEARLS

The pathology of the lymphatic system in primary lymphedema is complicated. The involvement of lymph vessels and/or lymph nodes should be considered when deciding between treatment options and should be dealt with accordingly.

Because of very bad outcomes, the socalled “debulking” procedure should not be the treatment of choice for lymphedema.

The surgeon should always consider the lymph vascular status before the start of surgical treatment for lymphedema, including secondary lymphedema.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree