CHAPTER 31 Excisional Approaches for the Treatment of Lymphedema

KEY POINTS

There is still a role for excisional approaches to lymphedema.

Proper patient selection is extremely important.

Although the Charles procedure is rarely performed, it still has a significant role for properly selected patients.

There are numerous variations of the Charles procedure; many of these are very rarely performed and thus are mainly of historical interest.

Liposuction can be considered an excision procedure, and it is extremely useful for the reduction of limb volume (see Chapter 32).

Excisional procedures can be combined with physiologic procedures, such as lymphaticovenular anastomosis and vascularized lymph node transfer.

The surgical treatment of lymphedema has advanced with the introduction of microsurgical lymph node transfer and lymphatic venous bypass. However, countless patients still have debilitating lymphedema that is not amenable to such sophisticated procedures because of the surgeon’s lack of appropriate expertise, the patient’s disease status, or patient or surgeon preference.

Excisional surgeries are sometimes radical, but they are often the only treatment modalities appropriate for these patients. Such patients are frequently considered to have inoperable advanced disease, and they become victims of medical systems that refer them from physician to physician while offering dwindling treatment options.

Most early methods for the treatment of lymphedema, such as reductive management and radical excision, have been abandoned over the past century. However, the principles of such surgeries remain pertinent to patients with end-stage lymphedema. For carefully selected patients, these techniques can offer a significant amount of satisfaction and excellent end results.

As discussed throughout this book, lymphedema is a chronic pathologic state of the lymphatic system. Lymph accumulates in the subcutaneous tissues, where it causes increased volume and weight of the limb, skin tension, and disfigurement. 1 Lymphedema is generally categorized as congenital, infectious, or iatrogenic, although its exact cause is still not fully understood. In the United States, lymphedema occurs most commonly as a sequela of the treatment of a malignancy. 2 – 6 Elsewhere, especially in parts of the developing world, infection with Wuchereria bancrofti (filariasis) is the most common cause.

Lymphedema has traditionally been viewed as incurable or intractable. However, during recent years there have been significant advances in lymphedema genetics, diagnostic modalities, and conservative treatments (see Chapters 8 and 12). Nonsurgical treatments such as complex decongestive therapy and compressive garments are considered palliative; the aim is to prevent disease progression and provide symptomatic relief. These treatments are expensive and time consuming, have poor compliance rates, and do not address the changes that arise in patients with severe end-stage disease with chronic fibrosis. 7 Surgical reduction is a viable treatment option for patients with disfiguring and advanced lymphedema. In this chapter we describe both earlier and current excisional surgical treatment options for advanced lymphedema.

Patient Selection

The management of lymphedema has traditionally focused on conservative modalities. These medical treatments—compression therapy, complex decongestive physiotherapy using lymphedema-specific manual lymphatic drainage massage, and external sequential pneumatic compression devices—are often attempted before surgical therapy is considered. 8 These conservative modalities to enhance drainage have demonstrated success in cases of mild to moderate lymphedema, but they are associated with high patient-to-patient variability, partly because their success depends on patient compliance. 9 Discouragingly, a significant number of patients receive little benefit. In addition, these methods can be costly, time consuming, and uncomfortable, which reduces patient compliance still further. 7 , 10

The basis of this conservative approach stems partly from the idea that surgical intervention leads to considerable morbidity. Because surgery for lymphedema has a high complication rate that includes recurrence, infection, and wound-healing problems, it is often delayed. 11 Many clinicians recommend at least 2 years of conservative therapy before any form of surgical intervention is considered. 12 For patients with end-stage disease and large, fibrotic limbs, conservative therapy is often ineffective or is not properly instituted. For these patients excisional surgery has a definitive role and must be considered.

Lymphedema surgery involves reductive and reconstructive procedures. Reconstructive techniques rebuild the lymphatic channels through vascularized lymph node transfers, anastomoses between lymphatic channels and veins, and lymphatic grafts using lymphaticlymphatic anastomoses. These surgeries are beneficial during the early stages of lymphedema; however, they have not resulted in consistent improvement in patients with advanced disease because of the relatively minimal reduction in the fibrosclerotic tissue that is seen after lymphatic reconstruction is performed. 13 The role of microsurgery is generally limited to early disease, when the lymphatics are relatively healthy and the tissues are still soft and pliable. Chronically accumulated lymphatic fluid in the subcutaneous tissues causes cutaneous thickening, hypercellularity, progressive fibrosis, and increased adipose tissue. 14 Damage to lymphatic vessels is irreversible after prolonged disease, and attempts to restore lymph flow will be inadequate if they are attempted in patients with end-stage disease. Patients with advanced International Society of Lymphology stage III disease—elephantiasis with severe limb deformation, scleroindurative pachydermatitis, and widespread lymphostatic warts—are the ideal candidates for excisional surgical procedures. 15 Sometimes excisional and reconstructive techniques can be combined to enhance patient outcomes and improve aesthetics.

Excisional Techniques

THE CHARLES PROCEDURE

Reductive or excisional therapy is appropriate when conservative measures fail, when the extremities become massive and fibrotic, and when the disease is incapacitating. The surgical technique for this type of treatment is typified by the Charles procedure, which was named for Sir Richard Henry Havelock Charles and first described by him in 1912. 16 During the mid-1880s, Charles served as the chief medical officer of the Afghan Boundary Commission, which surveyed the land between British India and the Russian Empire. His service ultimately brought him to Calcutta, where he became a professor of surgery and anatomy at Bengal Medical College. 17 It is here that he first documented his technique of applying split-thickness skin grafts to debulked tissue for the treatment of lymphedema. 16 Although Charles did describe excisional surgery for advanced filarial lymphedema, his technique pertained primarily to the scrotum. He documented one case of lower extremity lymphedema that was treated in this manner, but it was unsuccessful. 18 Despite a paucity of information about Charles’s treatment method, the procedure bears his name as a result of a series of references that can be traced back to a questionable citation by the British plastic surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe. 18 , 19

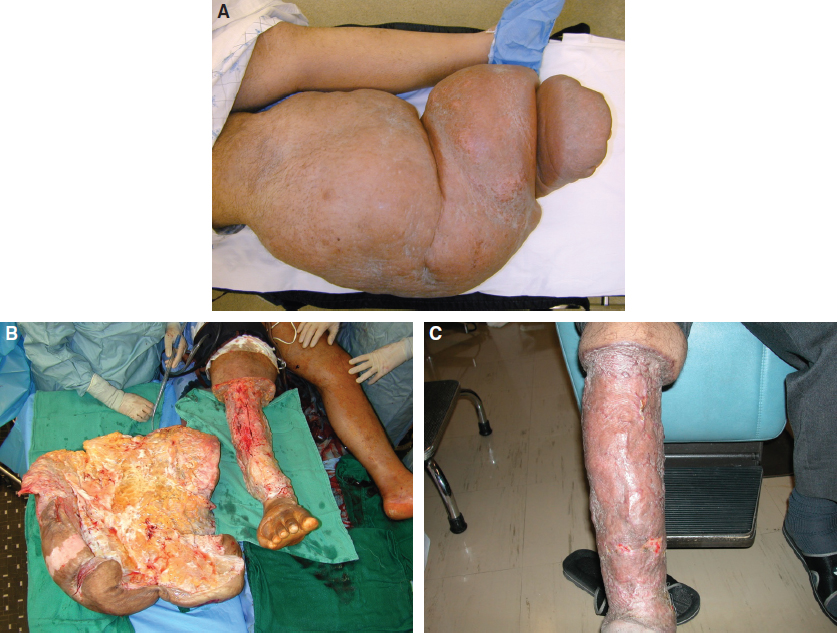

The Charles procedure involves total subcutaneous excision that removes virtually all skin, subcutaneous tissue (except in the foot and the region overlying the calcaneal tendon), and deep fascia; the bare muscle is subsequently reconstructed using skin grafts. Because there is no subdermal plexus for drainage and the skin graft is adherent to bare muscle, much worse edema is produced distal to the excision, usually in the foot. Severe secondary skin changes—including ulceration, papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, keloid formation, hyperpigmentation, and a weeping dermatitis—in addition to chronic cellulitis frequently occur, especially if split-thickness grafts are used. 20 The extremity should ideally be resurfaced with more durable full-thickness grafts to prevent secondary deformity, although harvesting full-thickness grafts of a sufficient quantity is a challenge. 21 Most surgeons have modified the original technique to preserve the deep fascia; they then graft onto the fascia rather than the bare muscle. When this procedure is performed correctly for the carefully selected patient, it safely provides a consistent reduction in size, an improvement in function, and satisfactory results, although it may be deemed aesthetically unsatisfactory. Because of its poor cosmesis and associated bottleneck deformity, this procedure has almost been abandoned (Fig. 31-1).

Variations of the Charles Procedure

As the Charles procedure became more popular and Charles’s name recognition grew, several variations of the procedure were described. Sistrunk, Auchincloss, Homans, Macey, and Thompson all contributed to variations of the Charles procedure. 22 – 26 During these procedures, the limb was generally significantly reduced by excising an ellipse of the skin and soft tissue of the extremity and creating dermal flaps to avoid excessive skin grafting; variations arose with regard to the management of the underlying fascia and the method used to foster the drainage of superficial lymph channels through the deep collecting system. The following list presents a brief summary of the variations of the Charles procedure, which are described here for completeness and acknowledgment in surgical history:

The Kondoleon procedure (1912): The Kondoleon procedure was one of the earliest variations, and it involved the excision of the lymphedematous tissue as well as vertical strips of deep fascia; this was done to open the deep lymphatics to create communication between the superficial and deep lymphatics. Kondoleon believed that the fascia covering the muscles separated the superficial and deep lymphatic systems, and the goal of his procedure was to connect these two systems by removing the fascia. A large amount of skin and subcutaneous fat would be excised, and the skin was then allowed to become attached to the muscles. When the raw surfaces were opposed, it was believed that new blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics formed; thus the superficial lymphatic system would be connected with the deep system. However, the creation of a fascial window apparently did not work well. Only the tissue resection part of this procedure continues to be used and to be erroneously referred to as the Kondoleon procedure.

The Sistrunk procedure (1918): The Sistrunk procedure was a modification of the Kondoleon procedure. Walter Ellis Sistrunk (1880-1933) was an outstanding surgeon who spent a significant amount of his career as an associate professor of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. He is most known for an operation that cured thyroglossal duct cysts, and he excelled at the surgical treatment of the thyroid, breast, and colon. The lymphedematous tissue was excised, and larger window cuts in the deep fascia were created to allow for communication into the normal deep lymphatics. Sistrunk believed that the removal of large amounts of fascia was one of the very important modifications of his procedure. After the wedge excision of the skin and the lymphedematous tissue, the wound was sutured together for primary closure. This procedure is still commonly used when a large lymphedematous pannus requires excision, but the fascia is often left intact.

The Homans-Miller procedure (1936): The Homans-Miller procedure was a modification of the Kondoleon procedure that involved the use of particularly thin skin flaps to cover the resected area. With these flaps, Miller was able to achieve an aesthetically pleasing result. He elevated anterior and posterior flaps from both medial and lateral incisions; the flaps were approximately 1 cm thick. The underlying lymphedematous tissue was excised down to the muscle fascia, and the skin flaps were trimmed and sutured into position. Good aesthetic and functional results were obtained with this procedure, which is now considered by some to be the standard ablative approach for the treatment of forearm and upper extremity lymphedema. However, occasionally second or even third operations are required to obtain the maximum benefit.

The Thompson procedure (1962) 26 : The Thompson procedure was a combination type that incorporated techniques from both the Charles procedure and the Homans-Miller procedure. It uses the deepithelialized segment of skin as a kind of wick that was thought to absorb fluid, as well as to serve as a communication between the superficial and deep lymphatic systems. However, this is no longer used. Lymphedematous tissue under the skin flaps was excised, and the epidermis and part of the dermis of one of the skin flaps were shaved off with a Humby knife. This shaved flap was then buried under the opposite flap, deep to the deep fascia, like a Swiss roll.

The Macey procedure 22 : This is a variation of the other procedures and is no longer used. The skin and subcutaneous tissue were peeled back with the deep fascia, and split-thickness skin grafting was performed over the denuded area. The overlying pad of tissue was sutured back temporarily and then trimmed away 10 days later.

Kondoleon added the excision of strips of deep fascia to Charles’s procedure. Sistrunk modified Kondoleon’s procedure to excise greater amounts of fascia and subcutaneous tissue, and he introduced the raising of a skin flap to close the wound primarily. However, others reported that the deep fascia regrew within 3 months and that the uptake of lymph was the result of the rich vascular bed of the muscle rather than its lymphatic system. 27 When both the deep and superficial lymphatic systems were excised, the rich, vascular muscle bed remained, as proposed, the mechanism for lymph dispersal. 28 In 1962 Thompson 29 modified these procedures again with the belief that dermis, with its rich lymph supply, drained directly into the muscle rather than depending on transmission through the subcutaneous tissue. Harvey 30 described improved lymph flow as measured by radioiodinated human serum albumin after the Thompson procedure; others failed to corroborate this finding entirely and believed the improvements were the result of the excision of subcutaneous tissue. When cutaneous nerves were preserved and the excisional surgeries staged, as described by Miller et al, 31 good results were observed in clinical studies; improved radioiodinated human serum albumin clearance was also noted. Despite the many permutations of the excisional surgery, preoperative and postoperative care remained constant: strict bed rest to decrease edema. Miller et al 31 even suggested suspending the leg from an overhead bed frame with a Thomas splint to provide dependent drainage.

These approaches provided the most reasonable surgical compromise by offering reliable improvement and a minimum of unfavorable postoperative complications. Improvement was directly related to the amount of skin and subcutaneous tissue removed as well as to the personal care and attitude of each patient. These procedures all allowed improved skin hygiene, decreased risk of cellulitis and sepsis, and the easier application of compression garments. 32 However, the Charles procedure and its variations have been largely forgotten because of the availability of nonoperative treatments, the potential morbidity of such radical surgeries, and the associated complications. These ideas are rooted in many of the original descriptions of excisional surgery that date back to the early 1900s, when aggressive debulking was used. At that time, difficulty maintaining a clean operative field when addressing large wounds may have negatively affected results. 18 Furthermore, these procedures were applied to all patients with lymphedema, without specific selection criteria and regardless of the cause, stage, or type of lymphedema present. 33

These excisional surgeries were once appreciated and used widely. However, since the middle of the last century, there have been few reported cases in the literature. A recent review showed that during the past 50 years, only 147 patients who had undergone the Charles procedure or one of its modifications were reported in the literature. The earlier cases demonstrated poor results and substantial complications, including infections, poor wound healing, prolonged hospitalizations, long surgical scars, sensory nerve loss, graft necrosis, scar contracture, and the exacerbation of lymphedema below the excised area. 21 , 34 All of these complications arose from one major source of morbidity: difficulties encountered when handling large skin grafts. 35 These problems were amplified when the area to be grafted was extensive, such as a lower extremity. A total of six contemporary articles (excluding case reports) were identified as involving excisional procedures for the surgical treatment of lymphedema 11 , 32 , 36 – 39 (Table 31-1). Only two of the studies, both by Salgado et al, reported outcomes of volume reduction as a percentage reduction. 37 , 38 The mean follow-up time of these studies ranged from 13 months to 72 months, and variability with regard to study design, lymphedema staging, patient selection, and measurement technique compounded the results of these surgeries when they were analyzed as a group. Again, the paucity of data largely reflects the view of many that these procedures cause significant morbidity.

Author (year) | Study Design | Number of Patients | Site | Procedure | Follow-up (months) | Volume Reduction (%) | Measurement Technique |

Modolin et al (2006) 39 | Prospective | 17 | Penis/scrotum | Excision | 72 | Not reported | Not reported |

Salgado et al (2007) 37 | Retrospective | 15 | Lower extremity | Excision | 13 | 66 | Circumference |

Lee et al (2008) 11 | Retrospective | 22 | Lower extremity | Excision | 48 | Not reported | Volumetry and circumference |

Salgado et al (2009) 38 | Prospective | 11 | Upper extremity | Excision | 18 | 21 | Circumference |

van der Walt et al (2009) 36 | Retrospective | 8 | Lower extremity | Excision with negative pressure wound therapy | 27 | Not reported | Not reported |

Karri et al (2011) 32 | Retrospective | 27 | Lower extremity | Excision | 22 | Not reported | Not reported |

Recent developments and technologic innovations have repopularized excisional surgeries by allowing for minimal complications and good functional outcomes. Karri et al 32 reported subjective improvements in mobility with acceptable cosmetic results and low complication rates after performing the Charles procedure on 27 patients for the treatment of chronic lower extremity lymphedema. Specific variations in technique were made to reduce complications, including excision of lymphedematous tissue over the dorsum of the foot and the use of long skin strips to reduce hypertrophic scarring. van der Walt et al 36 demonstrated a modification of the Charles procedure by adding negative pressure wound therapy to the wound bed directly after excisional surgery to improve the bed’s quality for grafting. The results were uniformly good among the eight patients described, with no major complications and significant improvements in assessed functional scores. Lee et al 11 reported the successful treatment of end-stage lymphedema with a modified Auchincloss-Homan operation. The authors reported a low complication rate and better overall volume reduction as compared with the control group, which received conservative therapy. The importance of continued compression therapy postoperatively to maintain initial results was stressed. The Charles procedure has also been combined with vascularized lymph node transfers. Sapountzis et al 40 performed the first combined radical excisional procedure with vascularized lymph node transfer to reduce the need for secondary operations as well as the risk of recurrence. The use of negative pressure wound therapy greatly simplifies the management of large skin grafts, so it is our current practice to occasionally offer the Charles procedure to selected patients with extreme disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree