CHAPTER 6 Brow Lift Techniques

The brow and forehead are frequently a central focus of patients seeking facial rejuvenation. Senescent and actinic changes can significantly impact these areas and result in an aged or tired appearance, or even contribute to functional problems such as visual field obstruction. The rejuvenation of these areas is a critical part in the restoration of facial harmony and the reestablishment of a more youthful appearance.

Aesthetics

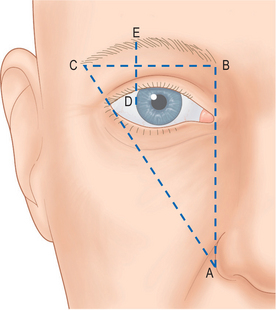

The absolute dimension of the forehead as measured from glabella to trichion, varies from patient to patient. The general characteristics of a pleasing brow have been well described.1,2 The brow and forehead create the upper one third of the face in the aesthetically proportioned face. The anterior hairline is typically 5–6 cm above the brow. The eyebrow forms a subtle arc that peaks at the junction of the middle and lateral thirds, which should correspond to a point above the lateral limbus. This arc is flatter in males. In females, the brow should be 3–5 mm above the superior orbital rim. In males, it should lie at the level of the orbital rim. Medially, the brow should begin at a line drawn perpendicular to the lateral aspect of the ala and passing through the medial canthus. The lateral brow is positioned slightly higher than the medial brow and should end at a point on a line drawn obliquely through the ala and lateral canthus (Fig. 6-1).

Anatomy

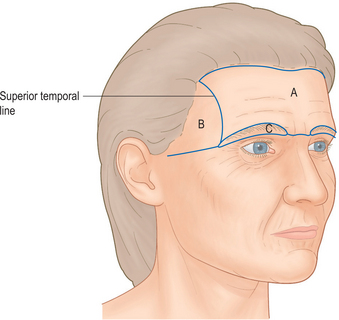

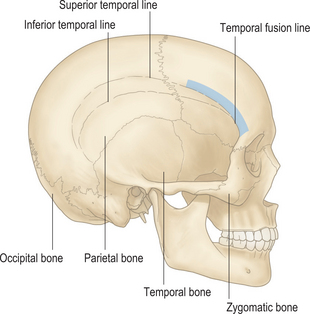

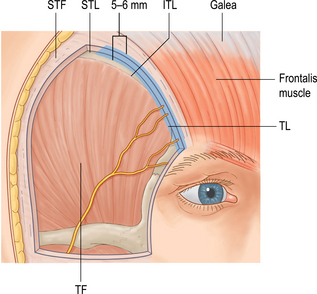

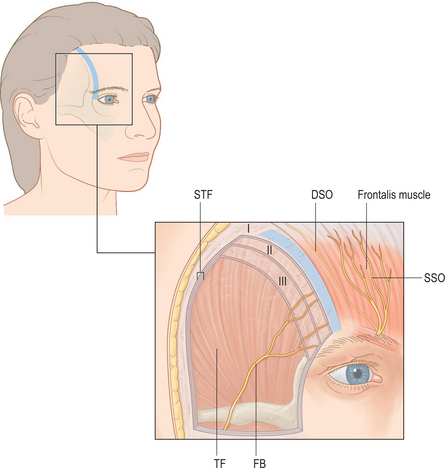

Landmarks for brow position are based upon the underlying bony anatomy. The superior orbital rim is easily palpable and serves as a fixed position for which to assess brow ptosis. Laterally, the temporal ridge delineates the border of the forehead from the temporal fossa (Fig. 6-2). Knize has identified the consistent relationship of several soft tissue structures to the temporal ridge. In this location the soft tissue layers of the forehead and scalp fuse with the periosteum at the zone of fixation (Figs 6-3 & 6-4).

A very important and easily overlooked anatomic variable to consider is calvarial thickness, as many of the techniques of brow lifting involve placement of bony fixation to suspend the newly elevated brow. Calvarial thickness may be as thin as 1–2 mm in the temporal region and along the course of the middle meningeal artery.3

The soft tissue anatomy of the forehead, similar to other regions of the face and neck, is arranged in multiple often very subtle layers (Fig. 6-5). The upper forehead is arranged similarly to the scalp with well-defined layers consisting of skin, subcutaneous tissue, galea aponeurosis, loose areolar tissue, and periosteum. At the origin of the frontalis the galea aponeurosis splits into a superficial and deep plane to encase this musculature. The deep plane splits again in the midforehead region to surround the galeal fat pad, and caudal to the fat pad splits again to form the glide plane space of the brow. The periosteum, subgaleal space, and deep galeal plane are discrete layers except in the lower forehead where these layers fuse and are firmly affixed to the frontal bone. Similarly, the periosteum is relatively loosely attached to the frontal bone over the upper and midforehead, but is firmly attached across the lower forehead.

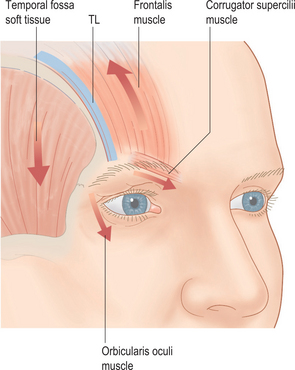

Movement of the brow is produced through the action of brow elevators and depressors, and is enhanced by the presence of the galeal fat pad, glide plane space, and subgaleal space. The major elevator of the brow is the paired frontalis muscle. The frontalis originates from the galeal aponeurosis and inserts into the dermis of the lower forehead. At the level of its insertion, the frontalis interdigitates with fibers of the orbicularis oculi and procerus. As the frontalis contracts and pulls on the orbital portion of the orbicularis, it indirectly elevates the brow via orbicularis dermal insertions.

Sensation of the forehead is provided mostly by the branches of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve, both arising from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve and emerging with their correspondingly named artery. The supratrochlear nerve pierces the corrugator muscle to provide sensation to the midforehead. The supraorbital nerve provides sensation to the lateral forehead and anterior scalp. It exits from the orbit and splits into a superficial and deep branch. The superficial branch exits the orbit through its foramen or notch and enters the frontalis muscle. It continues cephalad through the frontalis and transitions to a subcutaneous plane running over the surface of the frontalis muscle. This location renders it relatively well-protected from injury during brow lift procedures. The deep branch passes deep to the glide plane space of the brow and superficial to the periosteum initially and then travels superiolaterally through the galeal fat pad. After exiting the galeal fat pad the deep branch travels along the deep galeal plane passing parallel and approximately 0.5–1 cm medial to the superior temporal line. It arborizes into many smaller branches as it approaches the coronal sutures. Contrary to the superficial branch, the deep branch is susceptible to injury during brow lifting procedures. This branch may be injured during the initial incision or during elevation of the flap. Coronal incisions made to the subgaleal or subperiosteal planes always transect the deep branch at the level of the incision.4 The deep branch is also at risk lower over the forehead if the forehead flap is elevated in the subgaleal plane. To preserve the deep branch one must use a non-coronal incision and elevate the flap in the subperiosteal plane.4

Brow deformities

Brow ptosis is typically a major component of the age-related changes affecting the periorbital region. This is characterized by malposition of the brow and migration of brow skin into the superior lid region creating skin excess, loss of the normal supratarsal definition and lateral hooding. Although the exact mechanism is not clear, several factors have been proposed for the development of brow ptosis (Fig. 6-6).5 The frontalis muscle suspends the brow and resists the tendency for ptosis. The lateral-most limit of frontalis muscle resting tone extends to the zone of fixation along the temporal fusion line. Lateral to this region, the weight of the unsupported tissue mass over the temporal fossa in association with lateral orbicularis oculi and corrugator muscle activity contribute to the descent of the lateral brow.

Algorithmic approach to surgical rejuvenation of the brow

Brow lifting is performed more frequently today as part of a comprehensive facial rejuvenation. Available techniques include the coronal incision, the anterior hairline incision, the direct brow lift (midforehead incision), transpalpebral techniques, limited incision techniques, and endoscopic techniques. A survey of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons demonstrated that open techniques are performed with equal frequency as endoscopic techniques.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree