Breast Reduction: Inverted-T Technique

Scott L. Spear

Reduction mammoplasty is a clear example of the interface between reconstructive and aesthetic plastic surgery. The goals of the procedure are weight and volume reduction of the breast, but aesthetic enhancement is also an important goal, particularly in some women. Excellent procedures have been described and emphasis has shifted to technical refinements for improved safety and predictable aesthetic results. At the same time, greater importance has been placed on preservation of both sensation and physiologic function. Although there is a fundamental difference between reduction mammoplasty and mastopexy, both operations can follow the design of the techniques to be described for reduction mammoplasty alone (Chapter 56).

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

Sensory innervation to the superior portion of the breast is supplied by the supraclavicular nerves formed from the third and fourth branches of the cervical plexus. The medial breast skin is supplied by the anterior cutaneous divisions of the second through seventh intercostal nerves. The dominant innervation to the nipple is derived from the lateral cutaneous branch of the fourth intercostal nerve, whereas lateral cutaneous branches of other intercostal nerves travel subcutaneously to and beyond the midclavicular line. Independent confirmation of the importance of the lateral cutaneous branch of the fourth intercostal nerve has led to greater acceptance of techniques that include it in the vascular pedicle to the nipple.

There are three chief sources of blood supply to the breast. The internal mammary artery supplies the medial portion through medial perforators near the sternal border. The variable lateral thoracic artery supplies the lateral portion. The anterior and lateral branches of the intercostal vessels supply the remainder. Although there is a substantial degree of collateralization among these vessels in the breast parenchyma, it has been estimated that the internal mammary artery provides approximately 60% of the total. The lateral thoracic artery is thought to supply an additional 30%, primarily to the upper, outer, and lateral portions. The anterior and lateral branches of the third, fourth, and fifth posterior intercostal arteries supply the remaining lower outer breast quadrant. The variability and overlap between these vascular networks account for the remarkable safety of nipple-bearing pedicles of diverse design based on different vascular supplies.

The breast has two major venous drainage systems: one superficial and the other deep. The superficial drainage system is divided into two types: transverse and longitudinal. The transverse veins run medially in the subcutaneous space and empty into the internal mammary veins by multiple perforating vessels. The longitudinal drainage ascends to the suprasternal area to connect with the superficial veins of the lower neck. There are anastomotic connections across the midline, but only between the superficial systems. The major portion of the deep drainage is through perforating branches of the internal mammary vein. Additional venous drainage is in the direction of the axillary vein. A remaining route of drainage is posteriorly through perforators into the intercostal veins, which carry blood posteriorly to the vertebral veins.

The lymphatic pathways draining the breast parallel closely the venous pathways and include cutaneous, internal mammary, posterior intercostal, and axillary routes. Although most lymph flow is through the axillary region, the internal thoracic channels may carry 3% to 20% of the total.

Despite an extensive search for underlying metabolic causes of breast hypertrophy and gigantomastia, these conditions remain poorly understood phenomena, the products of end-organ hormonal sensitivity, genetic background, and overall body weight.

REDUCTION MAMMOPLASTY

Indications

Women seek to reduce the size of their breasts for both physical and psychological reasons. Heavy, pendulous breasts cause neck and back pain as well as grooves from the pressure of brassiere straps. The breasts themselves may be chronically painful, and the skin in the inframammary region is subject to maceration, irritation, and rashes. From a psychological point of view, excessively large breasts can be a troublesome focus of embarrassment for the teenager as well as the woman in her senior years. Unilateral hypertrophy with asymmetry heightens embarrassment. At a minimum, excessively large breasts can ultimately pose a liability for some women in terms of comfort, wearing clothes, and daily functioning, including many forms of exercise.

Inverted-T Techniques

Two decisions confront the surgeon: (a) choice of incision (scar) pattern and (b) choice of pedicle type. The inverted-T scar pattern can be applied to virtually any pedicle, including a superior pedicle, an inferior pedicle, a vertical bipedicle, a central mound pedicle, and a superomedial pedicle. The scar pattern and the pedicle type used in breast reduction are, for the most part, independent variables. Furthermore, there is no absolute cutoff regarding when an inverted-T scar pattern approach is appropriate instead of a vertical technique that avoids or attempts to avoid a transverse inframammary scar. At Georgetown University Hospital, we use both vertical techniques and inverted-T techniques, depending on the (a) size of the breast, (b) degree of ptosis, and (c) patient’s goals. Even when performing an inverted-T technique, we can virtually always shorten the transverse scar component because of our increasing experience with vertical scar techniques. The distinction, therefore, between vertical and inverted-T techniques has become less clear as surgeons add a short transverse scar to vertical techniques or shorten the transverse scar in inverted-T techniques.

The majority of American plastic surgeons still use an inverted-T scar pattern, most commonly with an inferior pedicle. Informal polls at recent breast meetings suggest that this preference is evolving with more surgeons opting for superomedial or central pedicles. There are several major advantages to the inferior pedicle with inverted-T scar technique. It is reproducible, straightforward, and easily taught. To a large extent, the skin incisions correspond to the underlying incisions that are made in the breast parenchyma itself. In this way, once the lines are drawn on the skin preoperatively, the cutting of the tissues and the closure of the wound proceed along the preoperatively planned lines. This has great

advantage in terms of predictability and reliability. In contrast, vertical scar techniques often involve a significant disparity between the skin incisions and underlying glandular incisions. A significant amount of intraoperative judgment and adjustment is required in vertical scar procedures in terms of both removing tissue and reshaping tissue to obtain an acceptable result. Finally, the closure of the skin may require adjustment to deal with the excess skin at the caudal end of the vertical incision (Chapter 56).

advantage in terms of predictability and reliability. In contrast, vertical scar techniques often involve a significant disparity between the skin incisions and underlying glandular incisions. A significant amount of intraoperative judgment and adjustment is required in vertical scar procedures in terms of both removing tissue and reshaping tissue to obtain an acceptable result. Finally, the closure of the skin may require adjustment to deal with the excess skin at the caudal end of the vertical incision (Chapter 56).

Once the decision has been made to perform a breast reduction, the surgeon must choose the orientation of the pedicle. This chapter describes the vertical bipedicle technique, the inferior pedicle technique, a central mound technique, and my preferred technique, the superomedial pedicle technique.

Vertical Pedicle Technique

McKissock first described his vertical bipedicle technique for nipple transposition during reduction mammoplasty in 1972. With this technique, the central breast is reduced to a vertically oriented bipedicle flap based superiorly on the upper margin of the new areolar window and inferiorly on the inframammary fold (IMF) and chest wall musculature. The flap carries the nipple-areola and, although de-epithelialized, depends primarily on the parenchyma for blood supply.

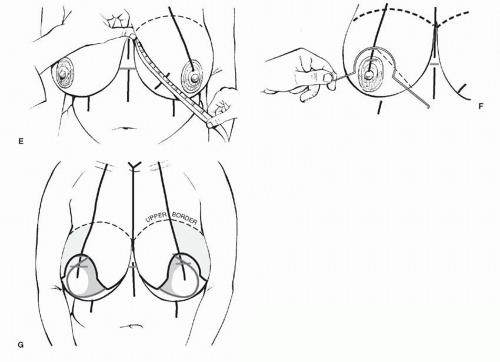

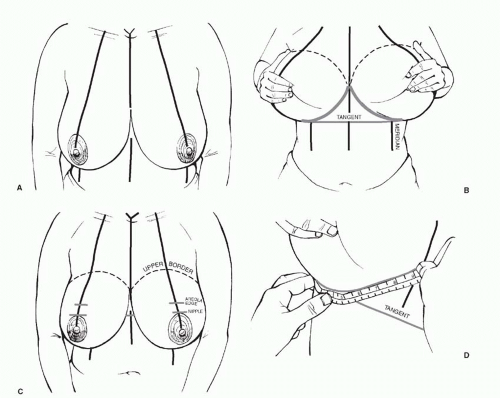

FIGURE 55.1. Preoperative markings. A. Drawing the basic landmarks, including the midline and breast meridian, for most breast procedures. B. A tangent is drawn from the lower most portion of the IMF across the midline. C. This tangent is then superimposed onto the surface of the breast. D. The length of the fold is then measured. It is often between 20 and 24 cm long. E. An arc that is just over one-half the length of the fold is transposed onto the surface of the breast medially. F. A wire keyhole pattern (which is centered around the nipple site) can then be superimposed on the breast such that it crosses the arc line drawn in Figure 55.4. G. The keyhole pattern is completed by making the limbs the desired length, anywhere from 5 to 8 cm long, depending on the size of the breast. It is important to double-check that the length of these proposed superiorly based lateral and medial flaps along their cut, free, inferior edges matches the length of the fold to which they are to be approximated. |

With the patient erect, the markings are made in a fashion similar to all breast reductions (Figure 55.1). The midline is drawn and the breast meridian is established by dropping a line from the midclavicle through the nipple and continuing inferiorly across the IMF. The IMF is marked, and a tangent to the fold is drawn across the lower thorax and transposed to the anterior breast and marked on the breast meridian. Whereas the initial descriptions set the nipple some 2 cm higher, the best location for the new nipple position may be at the IMF level depending on where the patient’s breast parenchyma is situated. In patients with an empty upper breast, it is important to keep the new nipple location centered or near where the breast volume lies or is expected to lie at the end of the procedure. The entire length of the IMF is measured with a tape measure. In most cases, it is between 20 and 24 cm long. Using a tape, a mark is made in the shape of a short arc on the surface of the breast that measures just over

one-half the length of the fold (e.g., for a 22-cm fold, the distance would be 12 to 13 cm). Diverging lines are then drawn from the new nipple point; they pass as tangents to either side of the existing areola and meet the arc line drawn from the ends of the IMF. A wire keyhole pattern is then adjusted to a similar angle of divergence and superimposed on the lines, indicating the proper size and location of the new areolar window. The length of the limbs of the pattern is 5 to 8 cm. From these extremities, lines are directed medially and laterally to intersect the IMF.

one-half the length of the fold (e.g., for a 22-cm fold, the distance would be 12 to 13 cm). Diverging lines are then drawn from the new nipple point; they pass as tangents to either side of the existing areola and meet the arc line drawn from the ends of the IMF. A wire keyhole pattern is then adjusted to a similar angle of divergence and superimposed on the lines, indicating the proper size and location of the new areolar window. The length of the limbs of the pattern is 5 to 8 cm. From these extremities, lines are directed medially and laterally to intersect the IMF.

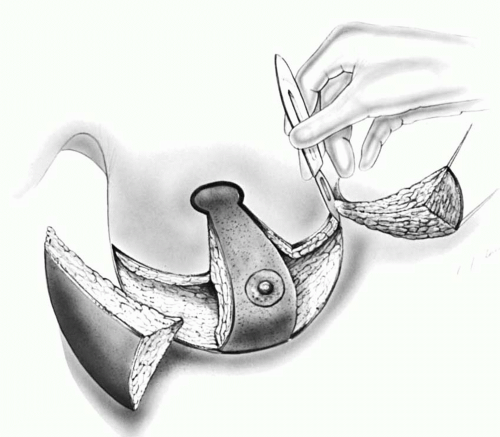

The new areola is circumscribed using a 42- to 48-mm cookie cutter within the existing areola. The vertical pedicle is outlined by extending the lines of the vertical limbs inferiorly to the IMF as two parallel lines straddling the breast meridian. The entire pedicle, except the reduced nipple-areola, is de-epithelialized. The vertical pedicle is then incised along its medial and lateral margins to the fascia of the underlying musculature, and medial and lateral dermoglandular wedges are resected (Figure 55.2). A thin layer of breast over the lateral musculature is retained to favor preservation of sensation to the nipple-areola complex. Additional breast tissue is resected from the remaining medial and lateral elements: little to none medially, but a considerable amount, including the axillary tail, laterally. A window of breast tissue is removed from the upper portion of the bipedicle flap, from the level of the nipple to the height of the keyhole pattern, creating a bucket-handle (Figure 55.3). This resection must not extend above the upper limit of the areolar window to avoid the loss of superior breast volume. The upper portion of this bipedicle flap should be kept at least 2 cm if not 3 cm thick. The flap from the upper edge of the now-reduced areola all the way to the IMF is left full thickness. The flap is folded superiorly on itself, bringing the areola into position within the keyhole pattern. The medial and lateral flaps are brought together over the pedicle, and closure is begun, working from the extremities toward the center (Figure 55.4). Any central excess of skin is either excised at the vertical closure, or “worked-in” to the closure. Specific strategies for fine-tuning the planned incisions and closure techniques apply to all the various pedicles and are addressed in detail when describing the author’s preferred technique later in this chapter.

Inferior Pedicle Technique

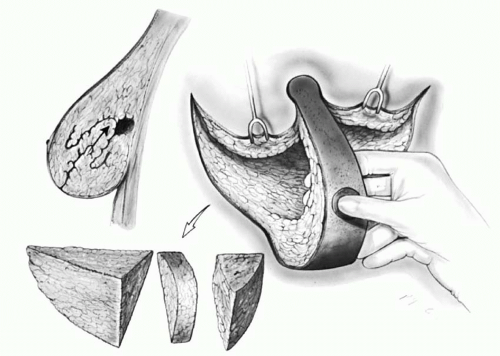

The inferior pedicle technique remains the most popular technique among U.S. plastic surgeons today. The planning of the inferior pedicle technique is essentially the same as for the McKissock bipedicle procedure, with the desired nipple location determined in the same manner. An inferiorly based dermoglandular pedicle is planned with a base of 4 to 9 cm at the IMF that gradually tapers as it ascends to encompass the nipple-areola complex. De-epithelialization with this technique is limited to the zone immediately about and inferior to the nipple-areola (Figure 55.5). Skin and parenchymal resections are performed not only medial and lateral to the pedicle, as described above, but also superior to the nipple-areola, up to the level of the keyhole pattern. These excisions are performed leaving a beveled carpet of breast tissue over the muscular fascia, especially laterally. Immediately superior to the 1-cm de-epithelialized cuff about the nipple-areola, the pedicle is terminated and incised down to muscle fascia, taking care not to undercut (Figure 55.6). A pyramidal pedicle of dermis and parenchyma is thus left deep to and inferior to the nipple-areola, based on the chest wall musculature and IMF. In the vicinity of the areola, it measures 2 to 4 cm in thickness, and near the base it is 4 to 10 cm. After completion of the breast resection, the nipple-areola is brought to the desired position in the keyhole pattern, and the medial and lateral flaps are brought together as with the McKissock technique (Figure 55.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree