Breast Reduction By Liposuction Alone

Martin Moskovitz

Introduction

Traditional breast reduction techniques use various incisions and pedicles to form a smaller and less ptotic breast. Technically, however, a breast reduction is an operation to reduce breast size. Ptosis correction, although desirable in many cases, has been a corequisite of breast reduction surgery due to prior limitations of surgical technology that required skin incisions to accomplish reduction. Traditional breast reduction removes large blocks of skin, fat, and glandular tissue, often in contiguous pieces. Pioneering surgeons were logical in designing access incisions that maximize ptosis correction because ptosis is a common concurrent condition. Liposuction, however, has provided plastic surgeons with a method to reduce breast size without incisions. Liposuction breast reduction (LBR) is an excellent method to reduce breast size with minimal scarring and can be used in a large segment of the population. In addition, LBR provides a rapid recovery with minimal complications.

Indications

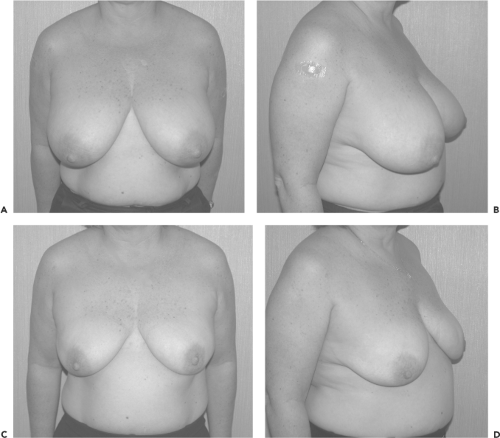

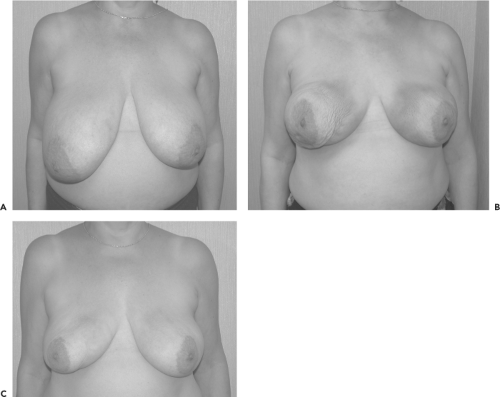

Breast hypertrophy is the obvious indication for reduction surgery. Candidates for LBR must have chief complaints directly related to their breast hypertrophy (Fig. 90.1). Pain, often in the neck, shoulder, and back, is a common complaint, and patients will often have a history of orthopedic or chiropractic care directed at these ailments. Intertrigo, poor posture, and bra-strap grooves are also common findings in breast hypertrophy patients. Difficulty with exercise and activities of daily living can also be directly attributable to hypertrophic breasts. Finally, although not necessarily medical conditions, difficulty finding proper clothing and awkwardness in social situations are common concerns for many patients with large breasts.

Candidates for LBR must also have a significant fatty component to their breasts. Patient biometrics and age are the best predictors of fat content. Patients with significant fatty deposits elsewhere on their bodies are those most likely to have fatty breasts amenable to LBR. Fatter patients tend to have fatter breasts, whereas thin patients often have predominantly glandular breast hypertrophy.

As patients age, they undergo significant glandular atrophy with replacement by fat. This process increases the success rate of LBR in older patients. Although many patients in their teens and 20s will do well with LBR, patients older than 40 years will almost universally have a successful outcome.

Asymmetry is another excellent indication for LBR. Traditional asymmetry correction relies on excisional techniques, breast implant placement, or a combination of the two procedures. These operations result in scars on the breast or possible long-term asymmetry due to implant action on one side of the chest alone. LBR removes mass without scars and does not introduce the unpredictable factor of unilateral implant placement. As long as patients will accept two breasts both of smaller proportion, LBR is an excellent alternative to traditional operations (Fig. 90.2).

Guidelines based on age, height, and weight are not universal or immutable, and there are relatively thin patients who have significant fat deposits in their breasts. Similarly, although the surgical success rate increases with age, many patients in their teens and 20s have excellent outcomes with LBR. It is important in preoperative discussions with LBR patients to give a general sense of the likelihood of successful reduction surgery based on the parameters available (Fig. 90.3).

There is currently no pragmatic preoperative test to assess fatty breast tissue volume. Mammography is unreliable in delineating the successful LBR patient because it is designed to look for calcifications and breast architectural abnormalities, not fat and glandular differences. Although radiologists often comment on glandular or fatty tissues in their official mammogram readings, in practice many patients with glandular readings have significant fatty deposits.

Some women note that their breast size increases with weight gain and decreases with weight reduction. This finding does have positive predictive value regarding LBR, and women with this situation will tend to do very well with LBR. This finding does not, however, have negative predictive value. Many patients do not lose weight in their breasts until they have achieved a state of near starvation, despite a significant fatty breast component, and they will do well with LBR surgery.

Physical examination is also limited in its ability to discern a fatty breast from a glandular one. Age and biometrics, therefore, remain the most useful predictors of success in LBR.

Concurrent medical conditions can also make LBR an intelligent alternative operation. Patients with conditions that preclude general anesthesia or a longer operating time make LBR a good option. Likewise, older patients in their 60s, 70s, and 80s may be better candidates for a faster procedure with a shorter recovery (Fig. 90.4).

Contraindications

The main contraindication for the use of LBR is a chief complaint of breast ptosis. Traditional breast reduction techniques, or mastopexy alone, are much better operations for those patients who complain predominantly of ptosis-related issues.

Many patients complain of both size and ptosis issues. The majority of these patients are good candidates for LBR as long as they understand that ptosis correction will be limited to what the natural elastic recoil of their skin can supply. Patients desiring ptosis correction beyond what is possible by elastic recoil alone should be counseled to undergo traditional breast reduction surgery. Because there is no way to accurately predict how much ptosis correction can be gained through recoil, it is wise to give patients a “worst-case scenario” in which their ptosis remains unchanged. If patients think they would be satisfied

with smaller breasts and ptosis similar to their preoperative situation, they will usually be satisfied with the outcome of LBR. Ptosis will not increase after LBR because no new skin is created. In addition, the vast majority of patients will have a demonstrable ptosis correction, although often not of the magnitude possible with traditional mastopexy/reduction techniques.

with smaller breasts and ptosis similar to their preoperative situation, they will usually be satisfied with the outcome of LBR. Ptosis will not increase after LBR because no new skin is created. In addition, the vast majority of patients will have a demonstrable ptosis correction, although often not of the magnitude possible with traditional mastopexy/reduction techniques.

The fact that patients with a chief complaint of ptosis are not suitable candidates for LBR does not, however, mean that patients with ptosis cannot be treated. The key is that the chief complaint be size and weight related. Previous publications (1,2) limited the role of LBR to those breasts without ptosis and, by doing so, confined the scope of this operation to a small percentage of patients. This limitation was based on the idea that breast reduction must be accompanied by ptosis correction. A broader view of patient desires, however, has shown that many patients will accept residual postoperative ptosis if they can be spared the extensive scarring of traditional reduction techniques. Large individual series (3) and outcome studies (4) have shown that LBR can be administered to a wide range of patients with good results.

The other significant contraindication to LBR is breast hypertrophy due to glandular components. Cases of virginal hypertrophy and very thin patients with large breasts and little to no body fat will probably fail LBR and should be advised to undergo traditional breast reduction surgery.

Smokers can tolerate LBR well but do run a higher risk of skin-healing complications. Smokers should stop smoking 2 weeks before surgery and refrain from smoking for 2 weeks after surgery.

Patients with fibrocystic breast disease do not pose a problem for LBR, although patients should be told that although their breasts will be smaller, the overall character of their fibrocystic breast symptoms will not likely change. Patients

with ongoing breast conditions, such as recurrent infections or cancer, should be counseled to seek treatment of these issues before considering any breast surgery. Postpartum patients should wait 6 to 9 months from the time they stop all lactation until surgery to avoid rare complications such as galactocele.

with ongoing breast conditions, such as recurrent infections or cancer, should be counseled to seek treatment of these issues before considering any breast surgery. Postpartum patients should wait 6 to 9 months from the time they stop all lactation until surgery to avoid rare complications such as galactocele.

Surgical Technique

Preoperative Workup

The workup for LBR begins with a physical examination, including careful breast palpation to locate any masses or nipple discharge and examination of the skin for irregularities. Blood tests should include required preoperative laboratory tests based on the patient’s age and history. Mammography must be performed on all patients older than 40 years and those younger than 40 years with a significant family history of breast cancer. Studies have shown that many cases of breast cancer after traditional reduction mammoplasty take place in patients who did not have screening mammogram preoperatively (5).

Surgery

Few markings are needed for LBR. The “danger zone” is outlined from the clavicle inferiorly, roughly one hand’s-breadth (Fig. 90.5). Most hematomas will start from perforators off the lateral thoracic, acromiothoracic, and internal thoracic arteries, all of which lie high on the chest wall and far from the breast tissue to be resected. In the supine position, however, the delineation of the upper portion of the breast can be obscured, and the surgeon can inadvertently pass the cannula through this area, yielding little fat with a higher risk of hematoma. The most common site of bleeding is the acromiothoracic perforator located several centimeters inferior to the midpoint of the clavicle (6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree