Breast Reconstruction with An Autologous Latissimus Dorsi Flap with and Without Immediate Nipple Reconstruction

Emmanuel Delay

Introduction

Breast reconstruction is an integral part of the treatment of breast cancer, and an increasing number of patients benefit from immediate or delayed reconstruction (1). We frequently use autologous tissue because it gives results of excellent quality in the medium and long term (2,3) (shape, consistency, sensitivity, integration in the body image). Three types of flaps are available: the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap, free flaps, and the autologous latissimus dorsi flap (4).

The musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap was first described by Tansini in 1906 for reconstruction of the chest wall after breast amputation (5). Under the influence of Halsted, who was hostile to plastic surgery, coverage or reconstruction using this flap fell into disuse. Rediscovered in 1976 by Olivari, by the end of the 1970s the latissimus dorsi flap had become a major option in breast reconstruction (6). At that time, this flap made it possible to correct the deformities of radical mastectomy by providing a reliable source of muscular and cutaneous coverage, in particular to replace the pectoralis major muscle. Schneider began to use it in this way from 1977 onward (7), followed in 1979 by Bostwick, who presented the first large series of breast reconstructions combining the latissimus dorsi flap with insertion of an implant (8). Used in the classical manner, this flap provides skin and muscle coverage. The available tissue is adequate for partial breast reconstruction (9,10), but for total reconstruction a silicone implant is necessary to give volume and projection. This leads to complications in the long term, in particular capsular contracture, which detracts from the result in 10% to 40% of cases, depending on the series (11,12,13). From the 1980s onward, various authors proposed using the latissimus dorsi as an autologous flap (14,15,16), but this technique had few indications because the results were unsatisfactory and the dorsal sequelae were considered to be too marked, especially as the TRAM flap was being developed and became more widely known at this time. In the 1990s, McCraw et al. (17), Germann and Steinau (18), Barnett and Gianoutsos (19), and Delay et al. (20) modified this technique to improve the results and reduce the dorsal sequelae. Since 1993, we have been using the technique of autologous latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction as described in our 1998 article in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. In the early stages of our experience, we used it when a TRAM flap was contraindicated. The TRAM flap, which we had the pleasure of learning under the guidance of John Boswick and Carl Hartrampf in Atlanta, was at the time our reference technique. As our experience increased and we evaluated our intensive practice of breast reconstruction (personal experience of more than 100 reconstructions a year), our preference went to the autologous latissimus dorsi, which is now our principal technique. This flap has in fact progressively replaced the TRAM flap in our practice since the mid-1990s because the postoperative course is much simpler and it allows better management of local thoracic tissue, avoiding the patchwork effect on the breast. However, the volume of the reconstructed breast may be insufficient if the patient is very slim or if there is marked atrophy of the flap. The classic solution in such cases was secondary insertion of an implant under the flap. Of course the reconstruction was then no longer purely autologous, which had its own disadvantages, and the new breast was of less natural shape. In other cases, even if the overall result was good, a lack of projection or a localized defect (generally in the upper medial part of the breast called the décolleté area) detracted from the quality of the result. The development in our department and use since 1998 of lipomodeling of the reconstructed breast (see Chapter 77), which has many advantages and ideally completes autologous latissimus dorsi reconstruction, probably contributed to the predominant use of this flap.

This chapter presents our technique and its recent advances, the means of obtaining a purely autologous reconstruction, the indications and contraindications, the possible complications, the results that can be expected, and finally the advantages and drawbacks of autologous latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction.

Surgical Anatomy of the Autologous Latissimus Dorsi Flap

The Latissimus Dorsi Muscle

The latissimus dorsi is a flat, thin, but very wide muscle. It inserts anteriorly on the lower four ribs, where four attachments converge with the digitations of the obliquus externus abdominis. The medial and lower part of the muscle inserts on the thoracolumbar fascia, which extends over the spinous processes of the lower six thoracic vertebrae, the five lumbar vertebrae, the sacral vertebrae, and the posterior one third of the iliac crest. Its upper border covers the inferior angle of the scapula, where an accessory bundle of teres major is often observed. Together with the last-named feature, it defines the posterior wall of the axilla before ending its insertion at the bicipital groove of the humerus between the pectoralis major and the teres major tendons. Its deep aspect carries attachments that are common to latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior.

The vascular supply to the latissimus dorsi is of type V according to the Mathes–Nahai classification, with a main thoracodorsal pedicle and accessory segmental pedicles arising from the intercostal and lumbar arteries. The thoracodorsal pedicle is a branch of the subscapular artery arising from the axillary artery, which, proximally to distally, divides into the circumflex scapular, thoracodorsal, and serratus anterior arteries. If the thoracodorsal pedicle is ligated, the latissimus dorsi is supplied in a retrograde manner by the serratus anterior artery, which is itself fed from the intercostal arteries. The thoracodorsal vein is continued by the subscapular vein and then the axillary vein. In nine of ten cases, the artery and the vein arise at the same level of the axillary vessels, but in the remaining case the origin of the artery is on average 4 cm more proximal, and it then follows the course of the vein at the level of the circumflex scapular vessels.

When the thoracodorsal pedicle penetrates in the deep aspect of the latissimus dorsi, it divides into two branches of equal importance. The superior branch runs in a parallel fashion 3.5 cm within the upper margin of the muscle. The lateral branch runs similarly parallel 2 cm from the lateral margin of the muscle.

The motor nerve of latissimus dorsi arises from the thoracodorsal nerve originating from the posterior secondary trunk C6 to C8. Its origin is about 3 cm more internal than the vascular pedicle, which it then rejoins before penetrating the muscle, except in cases in which the origin of the artery is more proximal, with the nerve lying between the artery and the vein.

Functions of the Latissimus Dorsi Muscle

The latissimus dorsi allows adduction, backward movement, and internal rotation of the arm. It is therefore involved in weight-bearing movements such as walking with crutches and in vertical traction with the arms raised above the head. Its removal has little effect on daily living or the practice of amateur sports, but its lack is more greatly felt in cross-country skiing and particularly in rock climbing.

The Fatty Extensions of the Latissimus Dorsi Muscle

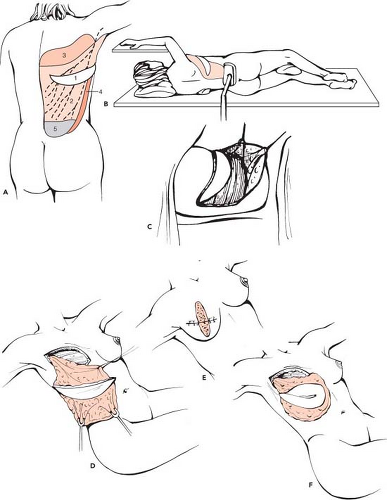

Because muscle atrophies after transfer when it is no longer used, the autologous latissimus dorsi flap aims to increase the volume provided by the latissimus dorsi by incorporating fatty areas that are true extensions to the flap. To codify these areas, as well as to make them easier to teach and to harvest, we have described six fatty areas (20) that are harvested as a complement to the muscle (Fig. 47.1):

Zone 1 corresponds to the fatty area of the crescent of the dorsal skin paddle.

Zone 2 represents the deep layer of fat lying between the muscle and the fascia superficialis and is left adherent over all the surface of the flap.

Zone 3 consists of the scapular hinge flap, which continues on the upper margin of the muscle.

Zone 4 lies just forward to its external margin, forming an anterior hinge flap.

Zone 5 corresponds to the suprailiac fat deposits or “love handles.”

Zone 6 is the adipose tissue of the deep aspect of the muscle.

The amount of fatty tissue gained depends on the extent of the patient’s fat deposits. However, even in slim patients, the volume gained is considerable. For example, a zone 2 with an area of 500 cm2 and a thickness of 0.5 cm provides a volume of 250 cm3 in addition to the muscular volume.

These zones are reliably vascularized by muscular perforating pedicles. Zone 3 has the advantage of a vascular plexus between the cutaneous branches (vertical branch of the circumflex scapular artery, intercostal branch, lateral thoracic branch) and two perforating pedicles of the thoracodorsal artery, which anastomose between themselves.

The Objectives of Breast Reconstruction

Whether the procedure is immediate or delayed, the objectives are clear: (a) to restore the skin, shape, volume, and consistency of the reconstructed breast, and (b) to reestablish the symmetry and harmony of the two breasts. From a technical viewpoint, the breast requires restoration of the container, or skin envelope, which must be recreated, and the content, or volume, which must be provided. In a second stage, 2 to 5 months later, when the reconstructed breast has found its new volume after atrophy of the muscle, it is time to consider creating breast symmetry when the nipple-areola complex is reconstructed.

Recreating the Cutaneous Envelope

Classically, the breast envelope was restored using the skin of the latissimus dorsi flap. This is still a good solution in rare cases in which the tissue of the chest wall is markedly damaged after radiotherapy. The disadvantage of incorporating a dorsal skin paddle on the breast is the ensuing patchwork effect, which gives a somewhat unnatural appearance to the reconstructed breast.

In the majority of cases, this patchwork effect can be avoided. In immediate reconstruction, the breast skin is preserved by skin-sparing mastectomy, which we have used since the beginning of 1992 with no particular technical or oncologic difficulties. In these cases, the small dorsal paddle is only used to reconstruct the nipple-areola complex, which can be done during the primary procedure if its position is respected. In delayed reconstruction, the skin of the breast

is replaced by adjacent skin from a thoracoabdominal advancement flap, which can be used even if the breast area has been irradiated. In the vast majority of cases, the skin supply is adequate for creation of the cutaneous envelope. The dorsal paddle is then no longer useful, and the flap is totally buried.

is replaced by adjacent skin from a thoracoabdominal advancement flap, which can be used even if the breast area has been irradiated. In the vast majority of cases, the skin supply is adequate for creation of the cutaneous envelope. The dorsal paddle is then no longer useful, and the flap is totally buried.

Recreating Volume

The autologous latissimus dorsi flap used in its extended form restores a volume similar to that of the opposite breast in 70% of cases.

The volume of the flap as a whole is increased by the systematic harvesting of six deep fat deposits adjacent to the muscle. The dorsal sequelae are reduced by raising a skin paddle of moderate width following the dorsal tension lines and sparing the fascia superficialis, which preserves a homogeneous superficial fatty layer. Use of the fascia superficialis during closure also reduces the tension of dorsal closure of the cutaneous plane and guarantees the stability of the scar over time. After 4 to 5 months, when there will be no further muscle atrophy, and despite the initial overcorrection, in 30% of cases volume is insufficient, and either complementary insertion of an implant or reduction of the opposite breast is required. Since 1998, we have found the solution to this problem by carrying out lipomodeling of the reconstructed breast 2 to 5 months after the first stage, during reconstruction of the nipple-areola complex. Lipomodeling (see Chapter 77) gives adequate volume in the large majority of cases. Only very slim patients who have no available fat deposits cannot benefit from this complementary technique.

Indications

Because of its reliable blood supply, the latissimus dorsi is a flap of choice, which can be used in the vast majority of clinical situations. Whether the patient is slim or overweight, her morphology is not in itself a contraindication to this technique.

All patients who present relative contraindications to the TRAM flap, such as smoking, diabetes, obesity, or extreme slenderness, or absolute contraindications, such as a previous TRAM flap or abdominal surgery (laparotomy, abdominoplasty), are candidates for the latissimus dorsi. In 1993, the TRAM flap was our primary choice when a patient wished an autologous reconstruction, and the autologous latissimus dorsi was reserved for cases in which the TRAM flap was contraindicated. However, with time and with increasing experience, the autologous latissimus dorsi progressively replaced the TRAM flap, which is now rarely indicated in our team. As used by us, the autologous latissimus dorsi flap strikes the best balance between the constraints involved and the quality of the results.

Contraindications

The contraindications of the autologous latissimus dorsi flap are very rare, and so it can be proposed in cases in which the TRAM flap is contraindicated. It is important to check for the existence of a muscular contraction by the resisted adduction test to ensure the presence of a functional latissimus dorsi with a preserved motor nerve. The preservation of the nerve is almost invariably accompanied by a patent thoracodorsal pedicle. However a nerve lesion does not contraindicate the raising of the flap or ligation of the subscapular artery if the anastomosis with the serratus anterior pedicle is intact. If there is any doubt (which is exceptional), it is necessary to begin elevation of the flap by checking the pedicle.

The following can be considered as systematic contraindications of the latissimus dorsi flap:

There is congenital absence of the latissimus dorsi.

There was a previous thoracotomy that transected the muscle on the same side.

There is a lesion of both the latissimus dorsi pedicle and the serratus anterior pedicle (which is absolutely exceptional).

There was massive axillary irradiation, which is now performed only in exceptional cases.

The patient refuses a scar in the back.

The benefits and drawbacks of this flap must be carefully considered in very athletic patients, who could be at a disadvantage if they are high-level practitioners of rock climbing or cross-country skiing.

Operative Technique

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative assessment will take into account all data obtained during a visit prior to the procedure (e.g., medical history, prior surgery, the patient’s wishes, evaluation of local tissue, opposite breast, possible donor sites).

Particular attention should be paid to the quantity of skin and fat that can be harvested in the laterodorsal region, assessing dorsal adiposity by pinching the natural laterodorsal pad. The fat available in the suprailiac region (love handles) should also be evaluated. The volume obtainable should be compared with the desired volume of the breast. If the back is thin, a small breast can be reconstructed; medium dorsal adiposity (2 cm thick) will allow reconstruction of a medium-sized breast; and marked dorsal adiposity will allow reconstruction of a large breast. If the estimated volume, after atrophy of the muscle, is inadequate when compared with the opposite breast, secondary lipomodeling should already be included in the operative planning. In addition, particular attention should be paid to the function of the latissimus dorsi, which, if good, generally indicates that the thoracodorsal pedicle is intact.

It should be carefully explained to the patient that there will be a horizontal, curved dorsal scar. During a visit, this can be marked out with a dermographic pencil so that the patient will be aware of its position and length. Because dorsal seroma is frequent, the patient must be informed of its likelihood and of the possibility of repeated postoperative aspiration to treat it. Finally, in the case of marked hypertrophy or ptosis, the need for a contralateral symmetry procedure at the same time as nipple-areola complex reconstruction should be considered, as well as the complementary lipomodeling.

Design

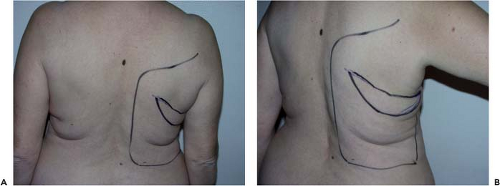

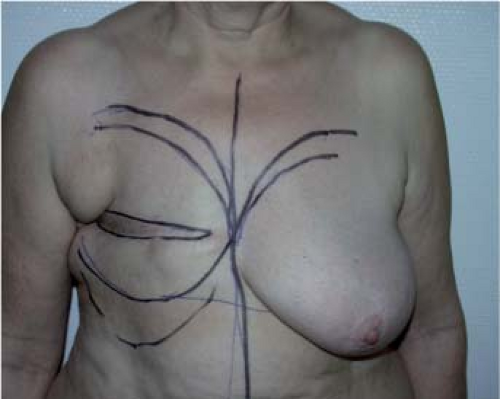

The reconstruction is designed with the patient in a standing or sitting position. She is asked to lean the bust sideways (Fig. 47.2)

in order to reveal the natural folds of the skin and fat. The dorsal skin paddle follows these lines, forming a crescent with a concave upper curve (Fig. 47.3). The amount of skin available should be carefully assessed by using the pinch test so that closure can be carried out entirely free from tension.

in order to reveal the natural folds of the skin and fat. The dorsal skin paddle follows these lines, forming a crescent with a concave upper curve (Fig. 47.3). The amount of skin available should be carefully assessed by using the pinch test so that closure can be carried out entirely free from tension.

Figure 47.2. Patient of age 50 years. Delayed breast reconstruction combining an autologous latissimus dorsi flap with an abdominal advancement flap (Figs. 47.2 to 47.21). The direction of the skin palette is found with the patient leaning sideways to reveal the natural skin folds. |

The medial extremity of the paddle lies between the inferior angle of the scapula and the spine, while the lateral extremity may extend a few centimeters beyond the anterior margin of the muscle, depending on the patient’s morphology. In delayed reconstructions with important a previous subaxillary dog ear from the mastectomy, it can be useful to integrate the dog ear into the flap to avoid a bigger dog ear after the abdominal advancement flap.

The curved residual scar may be designed to be partly concealed by the brassiere, but this is not of major importance, as it is generally of excellent quality. Marking of the area where the muscle lies and of the various fat deposits can help to judge the limits of undermining (Fig. 47.4).

Surgical Technique

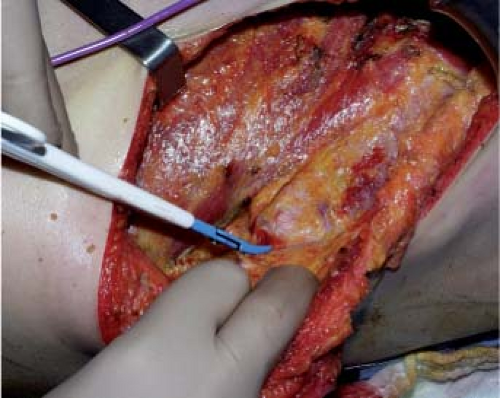

The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position, with the arm in abduction to open the axillary hollow (Fig. 47.5). Before any incision, the area to be undermined should be copiously infiltrated with physiologic saline (about 400 cc). This makes dissection under the fascia superficialis easier by giving it a more visible, pearly-white color and by reducing bleeding.

The skin paddle is incised by a single cut down to the fascia superficialis in order to preserve the subcutaneous blood

supply. Dissection then follows the deep aspect of the fascia superficialis, taking care to leave the deep fat on the muscle (zone 2). Sparing of the fascia superficialis best preserves the dorsal cutaneous blood supply and the undermined area is of homogeneous thickness (Fig. 47.6).

supply. Dissection then follows the deep aspect of the fascia superficialis, taking care to leave the deep fat on the muscle (zone 2). Sparing of the fascia superficialis best preserves the dorsal cutaneous blood supply and the undermined area is of homogeneous thickness (Fig. 47.6).

The upper part of the undermined area reaches the inferior angle of the scapula. In the internal part, the fascia superficialis is undermined up to the trapezius, whose lower lateral margin is exposed along all its length. The whole area of fatty tissue between the superior border of the latissimus dorsi, the trapezius, and the upper limit of undermining forms the surface of the scapular hinge flap (zone 3). To elevate the flap, first its superior horizontal margin is incised; then the flap is raised gradually by starting dissection in the extension of the lateral margin of the trapezius (Fig. 47.7). The scapular syssarcosis is then dissected. When the medial margin of the teres major is reached, the cutaneous prolongation of the circumflex scapular pedicle should be carefully ligated. Laterally, the hinge flap is dissected up to the medial margin of the latissimus dorsi. In its lower medial part, the rhomboid muscle should be carefully preserved, and the flap is raised like a hinge on the cranial margin of the latissimus dorsi until the point of the scapula is freed.

In the lower part, undermining should be a little wider than in the area of latissimus dorsi to make it easier to release the muscle later (Fig. 47.8). The lower limit lies a little above the iliac crests in order to harvest fat from the love handles (zone 5). In the medial part, the cutaneous perforators of the intercostal posterior arteries that lie above the transverse processes mark the limit. The whole length of the trapezius must be clearly identified to separate it from the paradorsal insertions of the latissimus dorsi. In the lateral part, dissection begins a few centimeters forward of the anterior margin of the latissimus dorsi in order to harvest fat in zone 4 (Fig. 47.9).

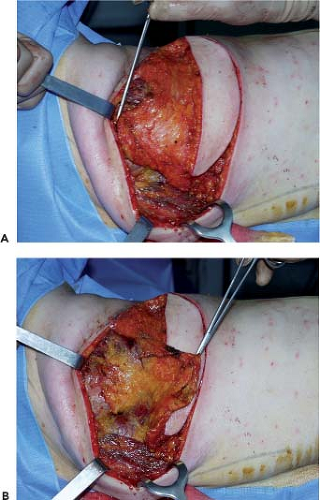

Figure 47.7. Elevation of the scapular fat flap (zone 3). A: Zone 3 before elevation. B: Zone 3 folded back as a hinge flap. |

The muscle is then separated at a deep level from the serratus anterior by starting at about 15 cm from the axilla because dissection is easy here. Submuscular undermining is continued

by harvesting the deep fat (zone 6) and by carefully ligating or coagulating the accessory pedicles. When the latissimus dorsi is completely undermined, its distal part is transected, from the deep part toward the surface, as horizontally as possible in order to include as much fat bulk as possible, in particular zone 5 of the flap (Figs. 47.10 to 47.13).

by harvesting the deep fat (zone 6) and by carefully ligating or coagulating the accessory pedicles. When the latissimus dorsi is completely undermined, its distal part is transected, from the deep part toward the surface, as horizontally as possible in order to include as much fat bulk as possible, in particular zone 5 of the flap (Figs. 47.10 to 47.13).

In the axillary region, the pedicle is then freed so that it can be transposed without tension or kinking, and the latissimus dorsi tendon is transacted (Fig. 47.14). The pedicle is approached posteriorly by releasing the teres major from the latissimus dorsi in a distal to proximal direction. Fibers that are common to the latissimus dorsi and the teres major and meet at the point of the scapula are transected. The two muscles are separated by remaining close to teres major (removing with the flap a small perimysium, which protects the pedicle); this is particularly important in breast reconstructions after axillary clearance, when this region may be fibrous, until the circumflex scapular pedicle is reached.

The origin of the latissimus dorsi pedicle is identified by following the pedicle of serratus anterior up to the Y-shaped bifurcation. The branch of the serratus anterior should be carefully preserved to ensure blood supply to the flap if there is a lesion of the thoracodorsal pedicle.

To make flap transposition easier, the scapular angular artery is ligated. When the pedicle has been identified, a finger is passed under the tendon (between the pedicle and the tendon) to protect it during partial proximal section of the tendon (Fig. 47.15). Only a muscle bridge a few millimeters in diameter is preserved in order to avoid any tension on the pedicle. The flap is then ready to be transposed to the breast area via a subcutaneous tunnel (Fig. 47.16). The donor site is closed after irrigation of the whole area of the undermining in order to obtain a perfect hemostasis (Fig. 47.17). Before closing the incision we do the quilting technique to reduce significantly the rate of seroma formation (see the section on

Complications). One suction drain is inserted, and then dorsal suture is started at the plane of the fascia superficialis, which reduces traction at the cutaneous level. The subcutaneous plane is closed, followed by a running intradermal suture. Before closure, we irrigate the undermined area with a long-acting local anesthetic such as Naropin (ropivacaine) to decrease postoperative pain on the first night (Figs. 47.18 to 47.21).

Complications). One suction drain is inserted, and then dorsal suture is started at the plane of the fascia superficialis, which reduces traction at the cutaneous level. The subcutaneous plane is closed, followed by a running intradermal suture. Before closure, we irrigate the undermined area with a long-acting local anesthetic such as Naropin (ropivacaine) to decrease postoperative pain on the first night (Figs. 47.18 to 47.21).

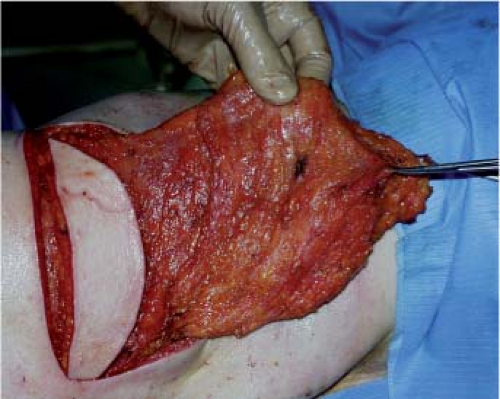

Figure 47.12. Fat in the area of the love handles (zone 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|