Breast Reconstruction: Tram Flap Techniques

James D. Namnoum

INTRODUCTION

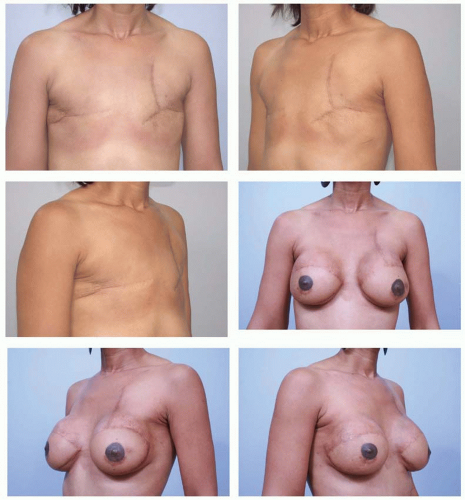

The transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap was introduced more than 30 years ago for breast reconstruction. Initially described by Holmstrom as a free flap, it was later popularized by Hartrampf, who independently conceived of its use as an abdominal island flap for breast reconstruction.1,2 Drawing on the work of Esser, Hartrampf theorized that the lower abdominal skin and fat could be transferred to the chest to create a breast mound based on circulation provided from the rectus abdominis muscle.3 The successful outcome in a patient with a history of implant failure following radical mastectomy ushered in a new era of breast reconstruction. The TRAM flap is unparalleled in its ability to provide a large volume of skin and fat for breast reconstruction. It is especially valuable in patients presenting for delayed reconstruction following mastectomy with post-mastectomy radiation. In these cases, the requirements for symmetry with the opposite breast often depend on extensive amounts of skin replacement as well as volume (Figure 61.1).

TYPES OF LOWER ABDOMINAL (TRAM) FLAPS

Lower abdominal flaps can be grouped into two main categories, pedicled TRAM and free flaps. The pedicled TRAM relies on perfusion from the superior epigastric system arborizing within the rectus muscle to provide perfusion to the lower abdominal tissues. In contrast, lower abdominal free flaps make use of the deep inferior epigastric system (free TRAM, MS-0, MS-1, MS-2; DIEP [deep inferior epigastric perforator], MS-3) or superficial inferior epigastric system (SIEA [superficial inferior epigastric artery] flap, MS-4); these systems are generally the dominant blood supply to the lower abdominal skin and fat (Chapter 62). With regard to muscle sacrifice and potential for donor-site weakness, bulge, or hernia following free flap harvest, MS-0 flaps make use of the entire rectus muscle while muscle-sparing MS-1 and MS-2 flaps sacrifice decreasing amounts of rectus muscle. MS-3 (DIEP) sacrifices no muscle but involves dissection and concomitant injury of a portion of rectus muscle and its intercostal innervation. MS-4 (SIEA) requires no muscular dissection or sacrifice. Not surprisingly, reduced muscular dissection and sacrifice is associated with decreased abdominal wall complications and improved abdominal wall strength.4,5,6 However, flap-related complications are higher in DIEP patients as opposed to non-muscle-sparing free TRAM patients (MS-0) owing to the reduced number of perforators supplying the tissues.7

INDICATIONS

The pedicled TRAM, free TRAM, and DIEP procedures may be indicated for patients who desire immediate or delayed breast reconstruction and are ideal for matching a ptotic opposite breast. Breast reconstruction utilizing tissues of the lower abdomen generally permits a softer, more natural reconstruction and tends to age in a similar fashion with the opposite breast as contrasted with device reconstructions (Chapter 59) (Figure 61.2). This potential improvement in softness and symmetry comes at the expense of a longer operative time and hospital stay, and an abdominal donor site that can result in abdominal weakness, bulge, or hernia. Often the resultant abdominal scar is positioned higher than would be considered aesthetically ideal and is a potential drawback to the procedure that should be discussed with the patient preoperatively (Figure 61.3). Many patients are erroneously led to believe that the TRAM flap is synonymous with an aesthetic abdominoplasty. While both may enhance the appearance of the lower abdomen, they are in fact quite different procedures. The differences should be clearly explained to the patients preoperatively to avoid unrealistic expectations.

While there are few absolute indications for one type of flap over others, several relative indications merit consideration. Selection of one technique over the other as a general rule takes into account the comfort level of the surgeon with the various techniques. For the surgeon who infrequently performs microvascular surgery, the free TRAM or DIEP flap is best avoided. Patients in high-risk categories such as those with a history of heavy cigarette use (greater than 10 pack/years smoking) and those who are overweight or obese are more suitable for free rather than pedicled TRAM reconstruction owing to improved flap perfusion and reduced rectus muscle sacrifice.8 This is particularly true for those undergoing bilateral reconstruction. In contrast, patients without significant comorbidity, elevated BMI, or heavy smoking history show no difference in incidence of flap or abdominal complications whether one (unipedicle) or two (bilateral single pedicle or double pedicle) pedicles are used, or whether a free TRAM flap is performed.9 Nahabedian has suggested an excellent algorithm for decision making regarding DIEP versus free TRAM selection. For patients requiring flaps less than 750 cc in volume in which a perforator of at least 1.5 mm can be identified, a DIEP flap can be safely selected; patients requiring larger flaps or having inadequate perforators (less than 1.5 mm perforators) are better candidates for muscle-sparing free TRAM flaps.

PEDICLED TRAM

The pedicled TRAM is still the preferred technique for breast reconstruction by most surgeons who perform the TRAM flap. However, microvascular procedures, particularly the DIEP flap, have gained significant popularity over the past 10 years.10 Advocates for the pedicled TRAM cite its reliability, predictable blood supply, ease and speed of harvest, safety in appropriately selected patients, and avoidance of a requirement for microvascular skills and instrumentation. The relative simplicity of flap harvest may afford more time for insetting and shaping, leading to superior aesthetic outcomes. The popularity of skin-sparing mastectomies has made this task considerably easier. TRAM flap procedures are somewhat more complex than the other options for breast reconstruction. As with other complex procedures, declining reimbursement has likely played a role in the popularity of simpler procedures for breast reconstruction such as expander/ implant reconstruction. It is interesting to note, though, that many surgeons who prefer autologous reconstruction are increasingly opting for more technically sophisticated procedures such as the DIEP flap for their patients. An analysis of the reasons behind this change is of great interest but beyond the scope of this chapter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree