CHAPTER 57 Breast reconstruction

Physical evaluation

• Cancer stage, status, and planned adjuvant therapy.

• Functional status (ambulation, weight, BMI).

• Medical history: specifically (diabetes, vascular disease and smoking) and other co-morbidities.

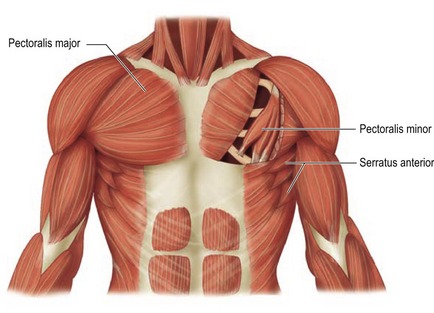

• Quantity and quality of remaining tissue (laxity, thickness, and condition of pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles).

• Body and breast morphology (breast dimensional analysis).

• Size of opposite breast/plan of opposite breast (prophylactic mastectomy).

• Availability of flap donor sites (evaluating scars, i.e. proximity of axillary dissection).

Anatomy

The breast is composed of both fatty tissue and glandular milk-producing tissues, and with age, the amount of fatty tissue increases as the glandular tissue diminishes. The soft tissues are supported by Cooper’s ligaments. They originate from the deep fascia and attach to the dermis and are considered to be the suspensory ligaments of the breast. The primary blood supply to the breast comes from the perforating branches of the internal mammary artery and all secondary blood supply come from the lateral thoracic, pectoral branches and the highest thoracic arteries. In addition lateral branches form the third, fourth and fifth posterior intercostal arteries. Sensory innervation of the breast is mainly derived from the anterolateral and anteromedial branches of thoracic intercostal nerves T3–T5. Supraclavicular nerves from the lower fibers of the cervical plexus also provide innervation to the upper and lateral portions of the breast. This overlap is thought to make the upper outer quadrant of the breast as the most sensitive portion. The lateral cutaneous branch of T4 is believed to be the primary innervation to the nipple. The breast lies over the musculature that encases the chest wall. The muscles involved include the pectoralis major, serratus anterior, external oblique, and rectus abdominus fascia. These muscles are very important both in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery since they provide additional soft tissue coverage.

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major muscle originates from the medial clavicle and lateral sternum and inserts on the humerus (Fig. 57.1). The major blood supply is thoracoacromial artery in addition to the intercostal perforators. The medial and lateral anterior thoracic nerves provide innervation for the muscle. The action of the pectoralis major is to flex, adduct, and rotate the arm medially. This muscle becomes important when additional soft tissue coverage is needed for an implant both in an aesthetic as well as a reconstructive setting.

Serratus anterior

The serratus anterior muscle runs along the anterolateral chest wall. Its origin is the outer surface of the upper borders of the first through eighth ribs and inserts on the deep surface of the scapula (see Fig. 57.1). Its vascular supply is derived equally from the lateral thoracic artery and branches from the thoracodorsal artery. The long thoracic nerve serves to innervate the serratus anterior, which acts to rotate the scapula, raising the point of the shoulder and drawing the scapula forward toward the body. To completely cover the implant with muscle in reconstructive surgery, often the serratus anterior must be elevated sharply to obtain the necessary coverage.

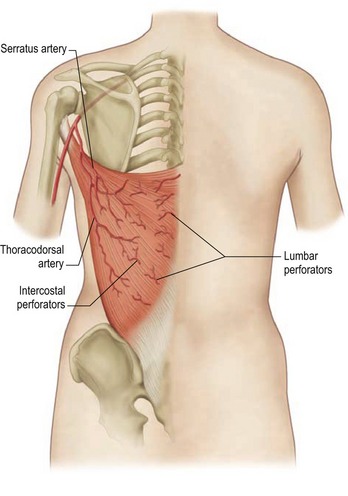

Latissimus dorsi

The latissimus dorsi muscle, which is a mirror image of the pectoralis major, arises from the lower thoracic vertebrae, the lumbar and sacral spinal processes, and the iliac crest. Its large, flat muscle belly converges into a flat tendon that inserts into the lesser tubercle of the humerus. The thoracodorsal artery provides the dominant vascular supply to the flap (Fig. 57.2). The subscapular artery originates from the axillary artery, gives off the circumflex scapular artery, and terminates in the thoracodorsal artery. This vessel, located in the posterior aspect of the axilla, gives off one or two serratus branches before entering the anterior undersurface of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The thoracodorsal artery is accompanied on its course by the thoracodorsal nerve and veins. The structures can be injured during an aggressive axillary dissection and therefore assessment of the pedicle in these patients is important in the preoperative planning.

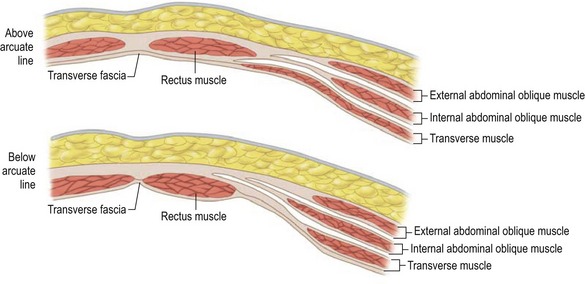

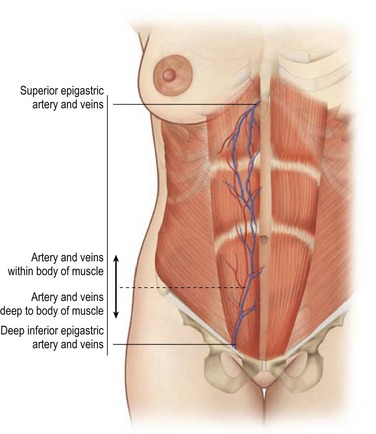

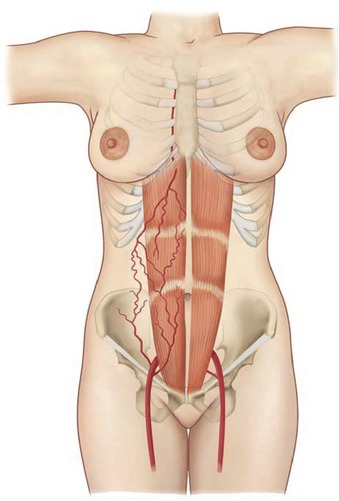

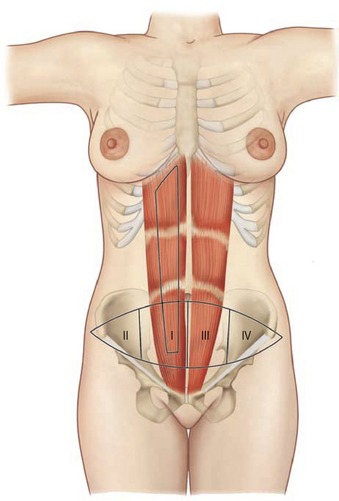

Rectus abdominus

The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate from the cartilage of the sixth, seventh, and eighth ribs and insert into the pubic tubercle and pubic crest (Fig. 57.3). The blood supply comes from the superior epigastric artery above and deep inferior epigastric artery below (Fig. 57.4). Within the muscle these main vascular sources may not have direct anastomoses with each other under normal physiologic conditions. Although the deep inferior epigastric system has been shown to be the primary vascular pedicle for this skin territory, the superior epigastric artery and vein are able to carry the lower abdominal soft tissue and comprise the vascular basis for the transverse rectus abdominis flap (Fig. 57.5). Additional blood supply is from the posterior perforating vessels accompanying the eighth through twelfth sensory and motor nerves. The musculocutaneous perforators that supply the flap are centered in the perumbilical area and emerge through the medial half of the rectus muscle to supply the subdermal plexus superficial to it (Fig. 57.6). Patient selection is important for this operation. Patients with an obese, pendulous abdominal panniculus, diabetics, and smokers carry a much higher risk of flap loss.

Technical steps

The indications for breast reconstruction have been liberalized as a result of increasing experience with the various procedures and recognition of the beneficial psychological effects of breast reconstruction. The most frequent reasons given for the reconstruction include: (1) to get rid of the need for an external breast prosthesis; (2) to be able to wear many different types of clothing; (3) to regain femininity; and (4) to feel whole again. The major reasons for not having reconstruction were a fear of complications and the perception of being too old for the procedure. Not surprisingly, the reconstructive cohort was the younger cohort. Clearly age and the lack of information may be significant factors in women’s reluctance to undergo breast reconstruction. The authors urge improved patient education on the risks and benefits of post-mastectomy reconstruction.

The current surgical options for post-mastectomy/lumpectomy reconstruction are as follows:

• Temporary skin expander subsequently exchanged for a permanent implant.

• Permanent expander implant requiring only valve removal.

• Permanent implant reconstruction.

• Latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap with implant or expander.

• Autogenous latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap.

• Transverse rectus abdominus musculocutaneous flap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree