2 Breast augmentation

Synopsis

Breast augmentation is the most common aesthetic procedure performed in the United States, and perhaps in the world.

Breast augmentation is the most common aesthetic procedure performed in the United States, and perhaps in the world.

In preparing for a breast augmentation, one must understand each patient’s goals and expectations and see if they can be achieved.

In preparing for a breast augmentation, one must understand each patient’s goals and expectations and see if they can be achieved.

Three important variables have to be addressed prior to surgery: 1. Incision length and placement (inframammary, periareolar, transaxillary, transumbilical); 2. Pocket plane (subfascial, subglandular, submuscular, subpectoral with dual plane 1,2,3); 3. Implant choice: (saline vs silicone, round vs anatomic, smooth vs textured).

Three important variables have to be addressed prior to surgery: 1. Incision length and placement (inframammary, periareolar, transaxillary, transumbilical); 2. Pocket plane (subfascial, subglandular, submuscular, subpectoral with dual plane 1,2,3); 3. Implant choice: (saline vs silicone, round vs anatomic, smooth vs textured).

Biodimensional planning may be utilized for optimal preoperative examination.

Biodimensional planning may be utilized for optimal preoperative examination.

Introduction

Glandular hypomastia may occur as a developmental or involutional process and affects a significant number of women in the United States. Developmental hypomastia is often seen as primary mammary hypoplasia, or as a sequela of thoracic hypoplasia (Poland syndrome) or other chest wall deformity. Involutional hypomastia may develop in the postpartum setting and may be exacerbated by breast-feeding or significant weight loss. When compared to the norm, inadequate breast volume may lead to a negative body image, feelings of inadequacy and to low self-esteem.1 These disturbances may adversely affect a patient’s interpersonal relationships, sexual fulfillment, and quality of life.2

There has been a steady increase in breast augmentation surgery with the emerging importance of body image, changes in societal expectations, and the increasing acceptance of aesthetic surgery in the United States. Augmentation mammaplasty was performed 289 000 times in 2009, as the most frequently performed cosmetic surgical procedure in women in the United States.3 In this chapter, we review the history of breast augmentation, operative planning and technique, and some perioperative and late complications of the procedure. The evolution of modern breast implants is described.

History

The first report of successful breast augmentation appeared in 1895 in which Czerny described transplanting a lipoma from the trunk to the breast in a patient deformed by a partial mastectomy.4 In 1954, Longacre described a local dermal-fat flap for augmentation of the breast.5 Eventually, both adipose tissue and omentum were also used to augment the breast.

During the 1950s and 1960s, breast augmentation with solid alloplastic materials was carried out using polyurethane, polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon), and expanded polyvinyl alcohol formaldehyde (Ivalon sponge). Ultimately, the use of these materials was discontinued after patients developed local tissue reactions, firmness, distortion of the breast, and significant discomfort.6 Various other solid and semi-solid materials have been injected directly into the breast parenchyma for augmentation including epoxy resin, shellac, beeswax, paraffin, petroleum jelly, and liquid silicone. Liquid silicone (polydimethyl siloxane) was originally developed in the aeronautics industry during the Second World War. In 1961, Uchida reported the injection of liquid silicone into the breast for breast augmentation.6 Unfortunately, injection of liquid silicone resulted in frequent complications including recurrent infections, chronic inflammation, drainage, granuloma formation and even necrosis.7,8 Breast augmentation by injection of free liquid silicone was abandoned in the United States in light of these complications.

The modern breast implant is a two-component prosthetic device manufactured with a nearly impermeable silicone elastomer shell filled with a stable filling material, consisting of either saline solution or silicone gel. This shell + filler implant was the Cronin–Gerow implant, developed in 1962, which used silicone gel as the filling material contained within a thin, smooth silicone elastomer shell.9 Since that time, both silicone gel and saline-filled implants have undergone several technical alterations and improvements with FDA approval of the fourth generation silicone implants in November of 2006.10

Basic science/disease process

Evolution of saline implants

The use of inflatable saline-filled breast implants was first reported in 1965 in France.7 The saline-filled implant was developed in order to allow the non-inflated implant to be introduced through a relatively small incision, and then inflating the implant in situ.8 Although the incidence of periprosthetic capsular contracture was lower with the saline-filled implants compared with the early silicone gel-filled implants, the deflation rate was initially quite high. The original saline-filled implants manufactured by Simiplast in France had a deflation rate of 75% at 3 years, and was subsequently withdrawn from the market. In 1968, the Heyer-Schulte Company introduced its version of the inflatable saline-filled breast implant (the Mentor 1-800) in the United States.

The thin, platinum-cured shell and the leaflet-style retention valve were two features of the early saline-filled implants that contributed to their high deflation rate.11 The silicone elastomer shell of the saline-filled implant has been improved by making it thicker and by employing new room-temperature vulcanization (RTV) process. This process is used in the manufacture of all saline-filled implant shells currently available from Allergan (formerly INAMED and McGhan Medical) and from Ethicon/Mentor Corporation.

Silicone chemistry

Silicone is a mixture of semi-inorganic polymeric molecules composed of varying length chains of polydimethyl siloxane [(CH3)2-SiO] monomers. The physical properties of silicones are quite variable depending on the average polymer chain length and the degree of cross-linking between the polymer chains.12 Liquid silicones are polymers with a relatively short average length and very little cross-linking. They have the consistency of an oily fluid and are frequently used as lubricants in pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Silicone gels can be produced of varying viscosity by progressively increasing the length of the polymer chains or the degree of cross-linking. The consistency of silicone gels may vary widely from a soft, sticky gel with fluid properties to a firm, cohesive gel exhibiting shape retention or form-stability depending upon the polymer chain length and the degree of cross-linking. Extensive chemical cross-linking of the silicone gel polymer will produce a solid form of silicone referred to as an elastomer with a flexible, rubber-like quality. Silicone elastomers are used for the manufacture of facial implants, tissue expanders, and the outer shell of all breast prostheses. The versatility of these compounds has made them indispensable in aerospace engineering, medical devices and the pharmaceutical industry.

Evolution of silicone implants

The first generation silicone gel-filled implant was the Cronin–Gerow implant, introduced in 1962 and manufactured by Dow Corning Corporation.9 The shell of the first generation implant was constructed using a thick, smooth silicone elastomer as a two-piece envelope with a seam along the periphery. The shell was filled with a moderately viscous silicone gel. The implant was anatomically shaped (teardrop) and had several Dacron fixation patches on the posterior aspect to help maintain the proper position of the implant. Unfortunately, these early devices had a relatively high contracture rate that encouraged implant manufacturers to develop second-generation silicone gel-filled implants.

In the 1970s, the second-generation silicone implants were developed in an effort to reduce the incidence of capsular contracture with a thinner, seamless shell and without Dacron patches incorporated into the shell. These implants were round in shape and filled with a less viscous silicone gel to promote a natural feel. However, the second-generation breast implants were plagued by diffusion or bleed of small silicone molecules into the periprosthetic intra-capsular space due to their thin, permeable shell and low viscosity silicone gel filler. This diffused silicone may be encountered as an oily, sticky residue surrounding the implant within the periprosthetic capsule during explantation of older silicone-filled implants. The phenomenon of silicone bleed has not been shown to create significant local or systemic problems.13

After the FDA required the temporary removal of third-generation silicone gel implants from the American market in 1992, the fourth-generation gel devices evolved for their market re-introduction. These silicone gel breast implants were designed under more stringent ASTM (American Society for Testing Methodology) and FDA-influenced criteria for shell thickness and gel cohesiveness. Furthermore, the fourth-generation devices were manufactured with improved quality control, and with a wider variety of surface textures and implant shapes. The fourth generation FDA approved gel devices are currently available from both breast implant manufactures in the united states.14–18

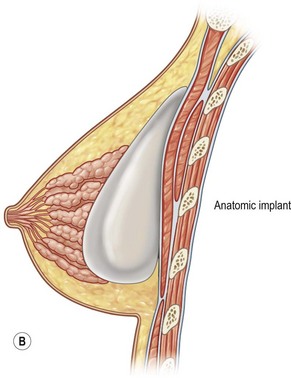

At the same time the concept of anatomically shaped implants with the evolution of the fifth-generation silicone gel implants, was introduced.19 These anatomically-shaped (Style 410) implants are available with a range of volumes and any of the twelve combinations of low, moderate, and full height with low, moderate, full and extra projection. The Contour Profile® Gel (CPG) implant has been designed by the Mentor Corporation with a more rounded and projecting lower pole and a flatter, more sloping upper pole to yield a more natural breast shape in breast augmentation and reconstruction. These implants are currently under FDA review.

Interestingly, silicone-containing compounds are ubiquitous in everyday life. The general public has been exposed to them for over 50 years in consumer products such as hairsprays, suntan lotions, and moisturizing creams. Silicones are extremely resistant to the action of enzymes when implanted into living tissue largely due to their hydrophobic nature.12 This makes silicone compounds extremely stable and inert. Silicones are often used in the consumer safety testing industry as the standard to which all other products are compared for biocompatibility.12 While elemental silicon and silicone particles are detected in the periprosthetic tissues, the biological significance of this finding remains undetermined and uncharacterized.20 In one study, no significant difference was found in levels of anti-silicone antibodies between patients who had silicone elastomer tissue expanders and control subjects.21

Several clinical studies have shown no difference in the incidence of autoimmune diseases in mastectomy patients receiving silicone gel implants compared to patients who had reconstruction with autogenous tissue.22–28 Even meta-analysis research combining data from over 87 000 women has revealed no association between silicone breast implants and connective tissue diseases.29,30 Notably, virtually all industrialized nations in the world except the United States use silicone gel implants almost exclusively for breast augmentation.

Diagnosis and patient presentation

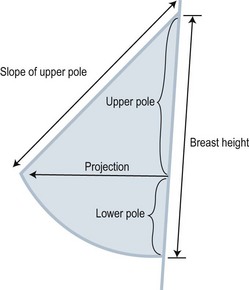

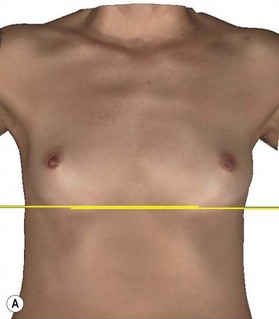

The ideal size and shape of the female breast is inherently subjective and relates to both personal preference and to cultural norms. However, most surgeons will agree that there are certain shared characteristics which represent the aesthetic ideal of the female breast form (Fig. 2.1). These characteristics include a profile with a sloping or full upper pole and a gently curved lower pole with the nipple-areola complex at the point of maximal projection. The breast structure itself may be thought of as the breast parenchyma resting on the anterior chest wall surrounded by a soft tissue envelope made up of skin and subcutaneous adipose. Clearly, the resulting form of the breast after augmentation mammaplasty will be determined by the dynamic interaction of the breast implant, the parenchyma, and the soft tissue envelope.31

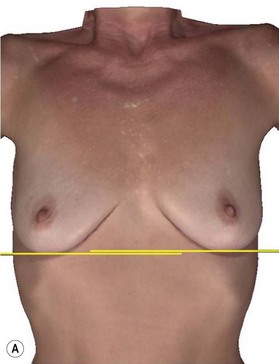

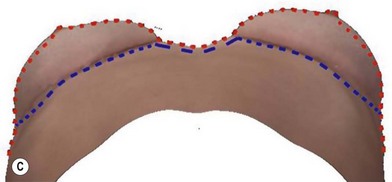

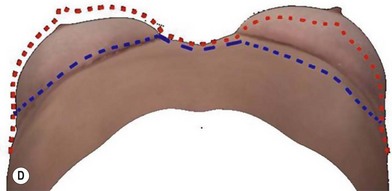

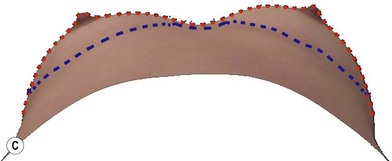

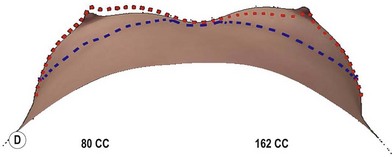

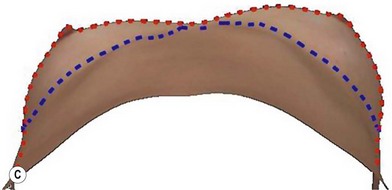

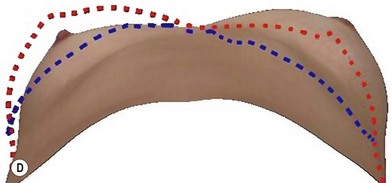

A thorough physical examination begins with observation and careful documentation of any signs of chest wall deformity or spinal curvature. It is imperative to document and draw attention to any asymmetry of breast size, nipple position, or inframammary fold (IMF) position. Careful palpation of all quadrants of the breast and axilla is required to rule out any dominant masses or suspicious lymph nodes. While palpating the breast, the surgeon should carefully assess the quantity and compliance of the parenchyma and soft tissue envelope. The soft tissue pinch test is useful method of assessment in which the superior pole of the breast is gathered between the examiner’s thumb and index finger and measuring the thickness of the intervening tissue. In general, a pinch test result of <2 cm will often indicate a need for subpectoral placement of the implant. It is also important to characterize the amount, quality and distribution of the breast parenchyma as it may be necessary to reshape or redistribute the parenchyma to achieve the desired shape of the breast mound. The elasticity of the skin should also be characterized by observing its resistance to deflection and noting any signs of skin redundancy or stretch marks. Both manufacturers have developed a preoperative planning system to facilitate patient assessment and implant selection. In addition, the authors utilize 4-D technology to asses both patient’s chest wall and soft tissue abnormalities. Chest wall, soft tissue asymmetries, and combinations of both are important to identify preoperatively (Figs 2.2–2.4). This tool is also utilized to understand patient’s perception of the desired look by showing the outcomes of utilizing different size and style implants. This is also then projected in the operating room for surgical planning.32

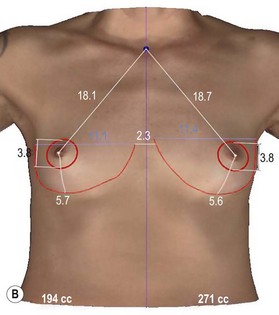

Patient selection

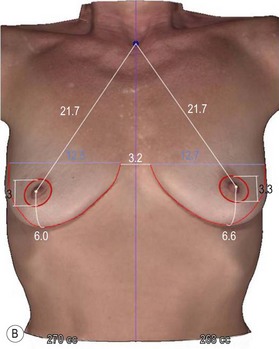

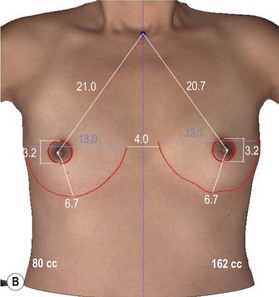

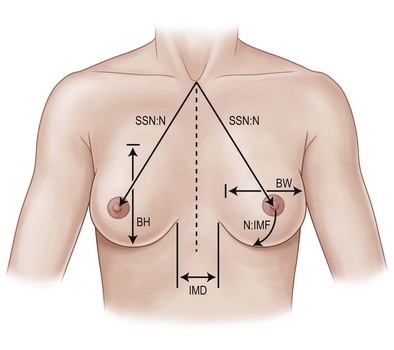

Precise measurements must be taken using the IMF, the nipple-areola complex, and the suprasternal notch as key landmarks (Fig. 2.5). The surgeon should measure the breast width (BW) at its widest point, the breast height (BH), and the distance from the nipple-areola complex to the inframammary fold (N : IMF). The distance from the suprasternal notch to the nipple areola complex (SSN : N) and the intermammary distance (IMD) should also be documented. It is often helpful to make markings on the patient in the seated position with a permanent marker just prior to surgery. It is imperative to mark the original IMF, and a good idea to mark the true midline of the anterior chest.

In addition to manual measurements, 3-D and 4-D systems are available to facilitate the measurement process in addition to enhancing the patients overall experience by increasing physician–patient interaction in selecting the appropriate implant.32 The visual display of the implant selected increases the confidence of the patient in the results that will be achieved. The 4-D imaging system (Precision Light Inc., Los Gatos, CA) automatically measures and characterizes both the soft tissue and chest wall as this is an important step in surgical planning. There are times that minor chest wall or soft tissue asymmetries are missed by manual measurement and visualization. This new system captures all of the asymmetries preoperatively so that appropriate preoperative planning can be performed and the patient is advised with an accurate informed consent.32 This system is based on the biodimensional principles as previously described. As we continue to pursue increased patient safety and satisfaction, while decreasing reoperation rates, this system will serve as another tool in our armamentarium to achieve these goals.

Operative planning

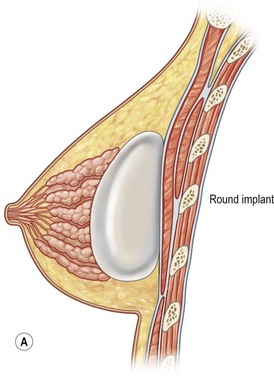

Pocket position

The decision of subglandular/subfascial or subpectoral implant placement depends on implant selection (fill and texture) and tissue thickness (Fig. 2.6). In theory, the best position for a mammary implant is in the subglandular plane. This is the most anatomically correct position to maintain natural shape and form. The authors, however, no longer utilize the subglandular plane and instead prefer the subfascial plane. The reasons for placement of implants in the subpectoral plane are to minimize the risk implant visibility and palpability. Risks of capsular contracture in either plane, is dependent on surgical preparation and technique and not necessarily the pocket. With sound surgical techniques and appropriate postoperative management, capsular contracture can be minimized in either pocket. Our belief is that the subfascial pocket is more superior to subglandular, as this provides an additional durable layer between the implant and the gland.

The subfascial implant position has been advocated for augmentation mammaplasty in certain patients (Fig. 2.7).33–37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree