Brachioplasty and Upper Trunk Contouring

Susan E. Downey

Aesthetic brachioplasty was first described by Correa-Inturrasape and Fernandez in 1954. Since this first description, modifications have been proposed to vary the placement of the scar, improve the contour of the upper trunk concomitantly, and minimize scarring.

A major advance came with the description by Lockwood in 1995 of brachioplasty with fixation of the superficial fascial system suspension. Lockwood postulated that loosening of the connections between superficial fascial system and the axillary fascia and loosening of the axillary fascia itself with age, weight changes, and gravitational pull yield a “loose hammock” effect, resulting in ptosis of the poster medial arm. Lockwood’s technique involves anchoring the arm flap to the axillary fascia.

Despite Lockwood’s advances many plastic surgeons did not routinely perform brachioplasties until the late 1990s when the obesity epidemic and the takeoff of bariatric procedures produced an influx of patients with laxity of all parts of their bodies. The majority of patients who present for brachioplasty have undergone massive weight loss which is reflected in the numbers reported by the American Society of Aesthetic Surgery. In 1997, there were 2,516 brachioplasties performed and in 2011 the number of brachioplasties had increased to 14,998.

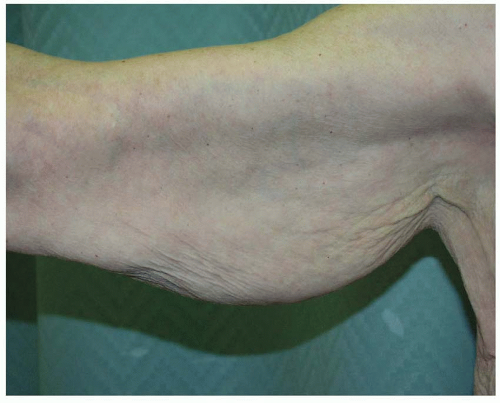

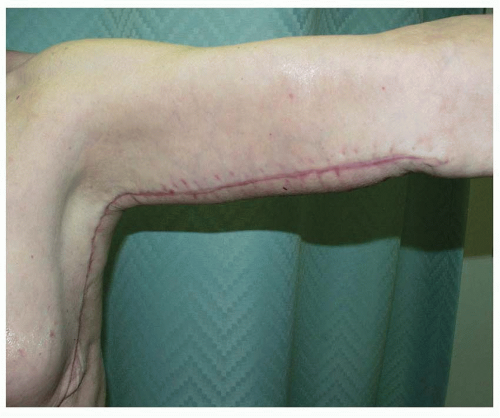

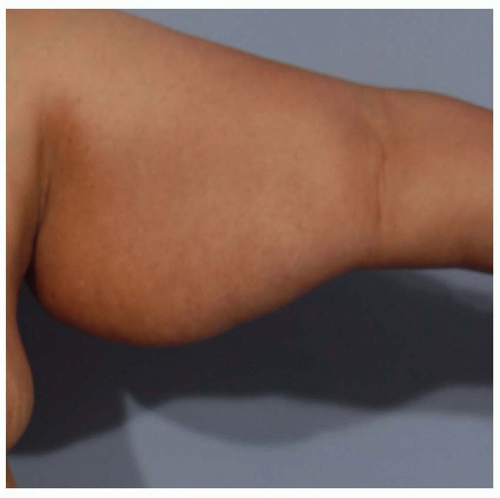

The arm and upper chest, like all other parts of the body, demonstrates great variation after massive weight loss. Attempts have been made to classify these deformities. Objective measurements such as the coefficient of Hoyer or the ratio of the height of the hanging skin have been described. Sacks described a technique pinching the excess skin between the fingers and measuring the length of excess skin. Strauch broke down the upper extremity into four zones to help define the deformities seen after massive weight loss. The zones are as follows: (1) zone 1 extends from the wrist to the medial epicondyle; (2) zone 2 extends from the medial epicondyle to the proximal axilla; (3) zone 3 is the anatomical borders of the axilla; and (4) zone 4 is the subaxillary upper lateral chest wall. Baroudi divides patients undergoing brachioplasty into three groups. Group 1 includes patients with moderate to firm skin and voluminous upper arm fat deposits. Group 2 includes patients with flabby skin and fat deposits. Group 3 includes patients with flaccid skin and no fat deposits. Appelt has described a classification that takes into account the amount of residual fat as well as the skin laxity to stratify the patients and determine which procedure is best in a given situation. Appelt’s classification system describes three different types of skin excess as well as fat excess. Type I patients have a relative excess of fatty deposits in the upper arm but have good skin tone and minimal laxity. These patients are good candidates for liposuction alone. Type II patients have moderate skin laxity with minimal excess fat. Type II is further broken down into IIA, IIB, and IIC. Type IIA patients have only proximal upper arm redundancy. This group of patient can also be broken down again into two groups: those with isolated horizontal laxity and those with both vertical and horizontal laxities. Patients with only isolated horizontal laxity can be treated with excision of a vertical ellipse with the scar in the axilla. Those with both longitudinal and horizontal excess can be treated with a T-shaped excision along the proximal anterior aspect of the upper arm. Type IIB patients have redundancy of their entire upper arm. These patients are candidates for a traditional brachioplasty with a scar from the elbow to axilla (Figures 68.1, 68.2, 68.3 and 68.4). Type IIC patients have laxity of the entire length of the arm and also along the chest wall. These patients are candidates for an extended brachioplasty, including excision not only of the excess arm skin but also along the lateral chest wall. Type III patients have both excess fat and redundant skin of the arm. These patients are counseled that a brachioplasty alone will not give them an aesthetically pleasing result. For these patients, staged liposuction and brachioplasty procedures or a combined single-stage liposuction and resection can be recommended (Figures 68.5, 68.6 and 68.7).

Patients with good skin tone and minimal laxity (Applets I) may undergo liposuction alone but care in patient selection is critical. The majority of patients with excess fatty deposits in the upper arm do not have good skin tone and will not be good candidates for liposuction alone. Grazer estimates that only 25% of patients presenting for upper extremity plastic surgery fall into this category. Only patients with a circumferential increase in fat volume but adequate skin turgor and elasticity will be happy after liposuction alone. Evaluation of the skin tone with the pinch test will provide information about whether the skin will shrink adequately.

The most significant drawback to brachioplasty is the long scar extending from the axilla to elbow. Limited incision brachioplasty or mini brachioplasty with the scars limited to the axillary region has been described. Ideal patients for this procedure have moderate amounts of skin and fat excess in the proximal third of the upper arm. This procedure can be combined with some liposuction to contour the upper arm. The excision is limited to the anterior and posterior limits of the axilla to hide the scars in this area with the arms at rest. This excision only removes the skin in one dimension (Figure 68.8). Patients with excess skin usually have two-dimensional excess and care must be taken before promising a scar that is isolated to the axilla. Skin quality and tone must be excellent. The limited brachioplasty only addresses skin excess in the longitudinal direction, whereas the full brachioplasty, with an incision extending to the elbow, addresses both longitudinal and transverse skin excess. In some cases, a small dart may be incorporated.

Although this will add a “T” incision to the procedure, doing so may refine the outcome for patients with focal horizontal excess.

Although this will add a “T” incision to the procedure, doing so may refine the outcome for patients with focal horizontal excess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree