I. HISTORY

A. The patient’s weight should be stable for 3 to 6 months for optimal results.

B. Medical comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and deep venous thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) are elicited to determine the risk of surgery. In some cases, such as with massive panniculectomy, the functional benefits of surgery may supersede the risks.

C. Social history includes recent smoking or nicotine use (50% risk of wound healing complications), plans for any future pregnancies, available social support network, and level of physical activity

D. Medications that inhibit wound healing (e.g., steroids that increase risk of dehiscence) or that increase perioperative risk (e.g., hormones and blood thinners) are noted and temporarily discontinued if possible

E. *All body contouring patients should be screened for unrealistic expectations, unhealthy external motivations, body dysmorphic disorders, eating disorders, and psychiatric history. Full disclosure regarding the pros and cons of the unique approach for each individual is paramount to success and patient satisfaction.

II. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A. Height, weight, BMI, and circumferences

B. Skin quality: Intertriginous rashes or ulcerations, presence of striae

C. Rectus diastasis and hernias

D. Preoperative abdominal scars

E. Symmetry

F. Fat distribution

G. Pinch test (assess thickness of subcutaneous fat)

1. ≥3 cm for liposuction of abdomen/hips/subtrochanteric areas

2. ≥2 cm for calves/ankles

H. Biggest issue—overall, the location and degree of adiposity versus skin laxity guides best surgical options—liposuction versus excision (or both). Most patients have mix of adiposity and laxity

1. Review the details of expected outcomes and limitations

2. Show the patient which areas are of greatest concern

3. Decide which approach to take (lipo or excision) versus using a combination of techniques

III. MASSIVE WEIGHT LOSS PATIENTS

A. Growing number of patients present after massive weight loss (MWL), either from diet and exercise or bariatric surgery

B. Body contouring may be considered once weight is stable

C. MWL patients have unique risk factors which contribute to postoperative complications and inferior aesthetic results

1. Relative avascularity of adipose tissue

2. Poor skin quality

______________

*Denotes common in-service examination topics

3. Musculofascial laxity. Some patients also have large abdominal hernias that will require repair by general surgery.

4. *Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery, especially protein, calcium, iron, and vitamins A, D, E, K, and B12

5. Body mass index. Greater risk of complications if BMI is >35

D. Discuss the patient’s desires versus likely outcomes and complications

E. Help the patient understand what insurance will and will not cover prior to committing to a surgical plan

F. Patient should be at stable weight for at least 6 months which is usually 12 to 18 months after their bypass surgery

G. Iintra-op fluids should include maintenance rate +10 mL/kg/h and close monitoring of post-op fluids and urine output

IV. LIPOSUCTION

A. Basics

1. Aspiration of subcutaneous fat using small diameter cannulas connected to source of high vacuum (1 atm or 760 mm Hg, enough to achieve vapor pressure)

2. Adherent fat avulsed by back and forth motion of cannula

3. Overlying skin shrinks to reduced fat volume

4. Fibrous stoma containing neurovascular bundles is resistant to suction

5. Best for fat deposits in patients with good skin elasticity who are unresponsive to diet/exercise

6. Cannulas

a. Surface irregularities reduced by smaller cannulas

b. Set back cannula holes (prevent suction in superficial compartment)

c. Size range = 1.5 to 6 mm

d. Three-holed “Mercedes” cannula most popular

B. Adipose tissue and cellulite

1. Adipocytes are produced in utero, early childhood, and early adolescence. After liposuction, adipocytes do not regenerate, but can hypertrophy with weight gain.

2. Retinacula cutis

a. Vertical fibrous septa connect the dermis to the underlying fascia, creating a “honeycomb” network to provide support to the fat

b. Cellulite refers to skin dimpling and irregularity from herniation of adipose tissue through the attenuated retinacula cutis

i. Primary cellulite (cellulite of adiposity) results from hypertrophied superficial fat and responds to weight loss

ii. Secondary cellulite (cellulite of laxity) results from generalized soft tissue redundancy and laxity. This is only correctable surgically.

3. Reserve fat of Illouz

a. Located deep to the superficial fascia (e.g., sub-Scarpa fat), this fat has horizontal fibrous septa.

b. Targeting this layer of fat during liposuction improves the overall contour with less risk of focal contour abnormalities.

C. Patient evaluation

1. Best candidates

a. Isolated areas of moderate adiposity, good skin elasticity, and turgor

b. Skin that does not “snap back” quickly when pinched will show redundancy after liposuction and can worsen the cosmetic appearance.

2. Striae, cellulite, abdominal pannus, and buttock ptosis respond poorly to liposuction and require surgical resection

D. Types of liposuction

1. Suction-assisted liposuction (SAL)

a. Indications: Excess fatty deposits, often in submental area, abdomen/flanks/lower back, thighs, medial knees, and calf/ankle

b. Mechanics: Removal of fat cells by direct mechanical avulsion aided by suction forces

c. Cannulas: Blunt tips with lumens ranging from 1.5 to 8 mm. Smaller lumen cannulas are less prone to creating contour irregularities.

d. Technique

i. Markings: With the patient standing, perform pinch test to identify areas of relative fatty excess

ii. Wetting solution: Fluid delivered to subcutaneous tissues prior to suctioning. It provides anesthesia and hemostasis.

a) *50 mL of 1% lidocaine and 1 mL of 1:1,000 epinephrine per liter of lactated Ringer solution = 0.05% lidocaine with 1:1,000,000 epinephrine (Use 30ml of lidocaine if larger than 4L liposuction planned).

b) Wet technique

1) 200 to 300 cc of fluid is infiltrated into the area

2) Blood loss is up to 30% of aspirate

c) Super wet technique

1) 1 cc of infiltrate per 1 cc of aspirate

2) *Blood loss is approximately 1% of the aspirated volume

d) Tumescent technique

1) *2 to 3 cc of infiltrate per 1 cc of aspirate

2) *Blood loss is approximately 1% of the aspirated volume

iii. Pretunneling is performed by passing the cannula multiple times without suction. This establishes a gliding plane at the correct level (deep to the superficial fascia) to prevent contour irregularities.

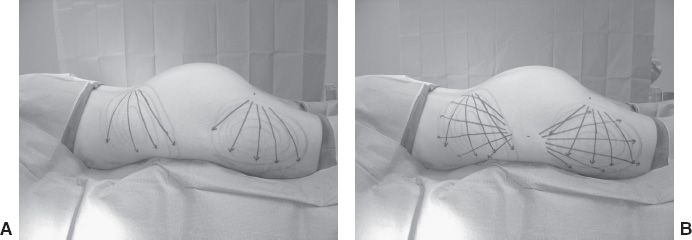

iv. Using a crisscross technique permits smooth transitions and improves contouring (Fig. 33-1)

v. *Too many cannula passes at the insertion site under suction can result in a contour depression due to focal over-resection.

e. Systemic complications (10% overall complication rate)

i. *Lidocaine toxicity

a) Symptoms include lightheadedness, visual disturbance, metallic taste, headache, perioral tingling, tinnitus, and seizure.

b) To minimize risk of toxicity, the wetting solution dose should be <35 mg/kg.

c) Timing and peak of absorption vary by body region—above the neck can occur in <6 hours, while thighs can take 12+ hours

1) Patients have reported symptoms starting 8 to 12 hours after the procedure.

2) When infiltrating multiple areas, avoid overlapping phases of absorption (e.g., do neck before thighs).

d) Lidocaine is not necessarily needed if the patient is under general anesthesia.

ii. Fluid imbalance

a) Hypervolemia and resultant edema are common early

Figure 33-1. Cross-tunneling technique.

b) *Hypovolemia can occur 12 to 36 hours postoperatively from fluid shifts. The risk is decreased with the use of super wet and tumescent techniques.

c) Electrolyte disturbances

iii. Pulmonary fat embolus: Can be increased in patients with low serum albumin.

iv. Pulmonary embolism: Increased risk with larger suction volumes and longer operations. Is most common cause of death.

v. Other complications: Contour irregularities, infection, seroma, hematoma, abdominal perforation, and skin pigment changes

2. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL)

a. UAL may be more effective in fibrofatty areas (e.g., breast, back, male chest, etc.)

b. Cavitation is created by pulsatile waves of ultrasonic energy, which preferentially liquefies adipocytes during suctioning.

c. An increased rate of seroma formation has been reported versus SAL.

d. Skin burns can be reduced by using more wetting solution to dissipate heat, and avoiding “end” hits against dermis.

3. Laser-assisted lipolysis (LAL)

a. LAL has been recommended for areas with skin laxity or potential for poor skin retraction after SAL.

b. Presumably, laser energy delivered to adipose tissue results in thermal lysis. The targeted chromophores are fat and water.

c. Smaller cannula probes are used (1 to 2 mm) and the most frequent laser is the 1,064 nm Nd:YAG

d. Outcomes are controversial

4. Power-assisted liposuction (PAL)

a. PAL is considered for fibrous or technically challenging areas.

b. This technique can reduce operative time, aspirate more fat per area, and result in less user fatigue.

5. Radiofrequency-assisted liposuction (RFAL)

a. RFAL uses bipolar radiofrequency energy to disrupt cell membranes and induce lipolysis.

b. The heat generated by RFAL can also burn the overlying skin.

V. ABDOMINOPLASTY

A. This operation removes redundant abdominal skin and fat between the umbilicus and pubis and can address abdominal wall laxity.

B. Etiology of laxity in skin, fascia, and muscles of the abdominal wall

1. Pregnancy: Results in abdominal wall laxity, rectus diastasis, and skin excess

2. Significant weight loss or gain causes dermatolipodystrophy, characterized by cellulite and reduced skin elasticity.

3. Aging causes an increase in visceral fat and skin laxity with a loss of elasticity.

4. Hereditary factors contribute to varying patterns of fat distribution and can predispose to abdominal laxity.

5. Ultraviolet radiation damages skin quality and reduces elasticity.

C. Anatomy

1. *Layers of the anterior abdominal wall lateral to the rectus muscles are skin, Camper’s fascia, fat, Scarpa’s fascia, reserve (subscarpal) fat, external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, transversalis fascia, and peritoneum

2. Scarpa’s fascia is contiguous with the superficial fascia in other regions of the body, forming the superficial fascial system (SFS).

3. Suprascarpal fat is thicker and denser than subscarpal fat.

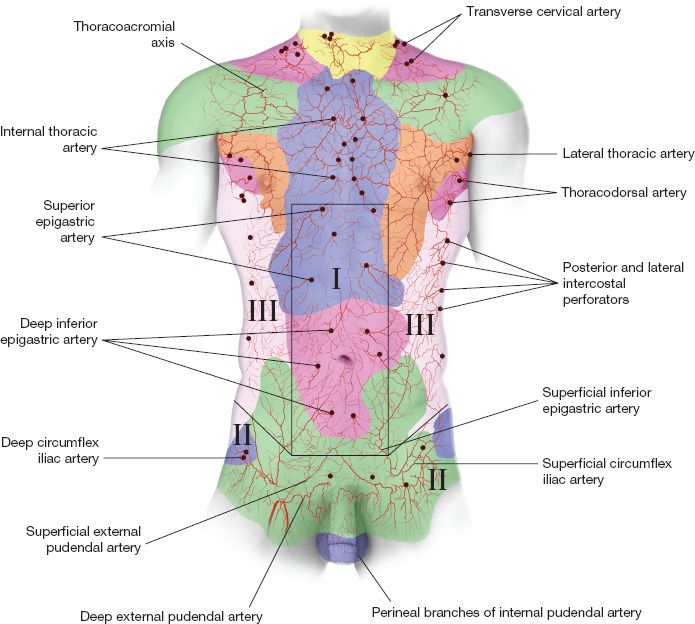

4. *Vascular anatomy of the abdominal wall (Fig. 33-2)

a. Huger zone I

i. Directly over the rectus abdominis

ii. Supplied by the deep superior and inferior epigastric arteries

Figure 33-2. Blood supply to the abdominal wall and Huger Zones.

b. Huger zone II

i. Inferolateral abdominal wall (inferior to line between anterior superior iliac spines down to inguinal crease)

ii. Supplied by the circumflex iliac system, superficial epigastric and superficial pudendal arteries

c. Huger zone III

i. Lateral over the external obliques

ii. Supplied by the segmental lumbar and intercostal perforators. The abdominoplasty flap relies on zone III perfusion.

5. Sensory innervation

a. The anterior abdominal wall: Innervated laterally from T6-L1, which run between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles

b. *The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (L2-3)

i. Provides sensation to the anterolateral thigh

ii. Located 1 to 6 cm medial to the ASIS, it can be injured during abdominoplasty dissection and closure

c. The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves can be injured with deep plication of the inferior rectus abdominis muscles

6. Abdominal wall musculature

a. Vertical layer (provides vertical pull)

i. Rectus abdominis

a) A varying degree of diastasis is normal.

b) *The arcuate line of Douglas is located half way between the umbilicus and the pubis: Inferior to this landmark, both anterior and posterior rectus fascias fuse and run superficial to the rectus muscles, leaving only transversalis fascia, a thin layer of pre-peritoneal fat, and parietal peritoneum deep to the rectus muscle

ii. External oblique

b. Horizontal layer (provides horizontal pull)

i. Internal oblique

ii. Transversus abdominis

7. Umbilicus

a. Small umbilical hernias may be repaired during abdominoplasty.

b. *Blood supply

i. Subdermal plexus

ii. Right and left deep inferior epigastric artery

iii. Ligamentum teres

iv. Median umbilical ligament

v. This allows for either preserving the umbilicus on its stalk or transecting it at its base

8. Gender differences

a. Men

i. More commonly have subscarpal fat deposits in the flanks, abdomen, and chest (Android distribution).

ii. Rectus diastasis occurs more in the upper abdomen.

iii. Redundant skin is less common, unless there has been massive weight loss.

iv. There is increased intra-abdominal fat with aging.

b. Women

i. More commonly have fat deposits in the lower abdomen, hips, and thighs (Gynecoid distribution)

ii. Rectus diastasis occurs more in the lower abdomen

iii. Skin redundancy or striae are more common and are exacerbated by pregnancy and weight loss.

D. Preoperative evaluation

1. COPD and other respiratory comorbidities have unique implications after abdominoplasty. Consider pre-operative pulmonary function tests to identify at-risk patients.

a. Increased risk of wound dehiscence with coughing

b. Baseline pulmonary compromise is worsened by restriction of expansion after rectus plication.

2. Physical examination

a. Identify areas of abdominal laxity and rectus diastasis

i. Epigastric fat. This region will become the entire abdomen. If prominent, results of abdominoplasty are less favorable. Simultaneous lipo in this area is likely to cause skin and fat necrosis.

ii. Skin laxity between the umbilicus and pubis—liposuction versus excise some versus excise all.

iii. Identify excess fat over hips and flanks that may benefit from liposuction.

iv. Excess soft tissue over hips that will not be excised during abdominoplasty should be shown to the patient

b. Palpate for hernias

c. Previous abdominal scars

i. A subcostal scar (e.g., Kocher incision) is a relative contraindication to a full abdominoplasty, as this incision interrupts Huger zone III.

ii. A midline abdominal incision disrupts cross-midline perfusion and can result in wound healing complications

a) Lower scars excised with the panus have no effect

b) Upper scars that will be transposed below the umbilicus are a relative contraindication and an absolute contraindication with combined liposuction

iii. Transverse upper abdominal scars transposed below the umbilicus may limit blood supply with full abdominoplasty.

iv. McBurney appendectomy incision: Little effect on surgical planning

v. Open cholecystectomy incision: Relative contraindication to a full abdominoplasty.

E. Relative contraindications

1. Prior abdominal scars

2. Plans for future pregnancy, which would cause re-expansion and laxity recurrence. Abdominoplasty will not inhibit the growth of a fetus.

3. Active changes in weight

4. Chronic medical conditions (e.g., DVT, COPD, DM, etc.) require appropriate medical clearances before surgery

5. Obese patients are poor abdominoplasty candidates. Significant intraabominal fat, relative avascularity, and generalized adiposity inhibit closure and predispose to wound healing complications.

6. Smoking or nicotine use is a contraindication to most surgeons

a. Risk of smoking and wound healing deficits after abdominoplasty in smokers: 12% to 14%.

b. Cutoff for pack years and risk of infection: 8.5.

F. Surgical techniques

1. Low transverse incisions should sit at least 5 to 7 cm above the vaginal introitus/penile base, at the superior level of the pubic hair.

2. Miniabdominoplasty

a. For patients with isolated lower abdominal contour deformity involving central skin excess and fascial laxity.

b. A conservative 6 to 15 cm ellipse of midline lower abdominal skin is resected without repositioning the umbilicus.

c. Rectus plication is performed inferior to the umbilicus under direct visualization and is optional above umbilicus with use of an endoscope.

3. Full abdominoplasty

a. For patients with significant skin excess, abdominal wall laxity, and rectus diastasis.

b. Discuss scar placement. Depending on type of pants and undergarment/bathing suit patient prefers, final scar location especially in relation to ASIS should be planned

c. The superior incision is usually made above the umbilicus, which must be exteriorized on a stalk and repositioned.

d. Undermine up to costal margins and xiphoid. Avoid dissecting further lateral than is needed so as to maximally preserve blood supply from the intercostal perforators.

e. The anterior rectus abdominis fascia is plicated from xiphoid to pubis to contour the abdominal wall.

f. During closure, the abdominal flap should be pulled medially. This tension will improve aesthetic contour of hips and waist.

g. Postoperative instructions include abdominal compression garments and no heavy lifting for 6 weeks.

4. Panniculectomy

a. This operation removes a large overhanging pannus (“fatty apron”) that can cause functional limitations, intertrigo, etc.

b. A large soft tissue wedge is designed around the pannus and excised.

c. Although similar in concept to abdominoplasty, panniculectomy alone does not include rectus plication and rarely involves umbilicus transposition.

5. Vertical component

a. Adding a vertical component to standard panniculectomy (resulting in a “fleur-de-lis” design) provides improved lateral contouring with the tradeoff of a long vertical midline scar extending to the xiphoid (Fig. 33-3).

b. Vertical excision is performed first to prevent over resection.

Figure 33-3. General markings for panniculectomy with vertical wedge resection (Fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty).

c. This technique results in a T-shaped scar, with limited blood supply at the junction of the flaps.

d. Minimize lateral undermining of to abdominal flaps to preserve blood supply.

e. Particularly useful in MWL patients, as they often have notable horizontal and vertical excess.

f. Important that superior and lateral ends of the excisions are done at sharply acute angles to prevent leaving a standing cutaneous deformity

G. Complications

1. The overall complication rate is 30%, with <5% major complications. Higher rates are seen in male patients. Overall complications are doubled in MWL patients.

2. Seroma (14%): Patients with diabetes and higher preoperative weight have increased incidence. Use of closed suction drains and progressive advancement suturing help reduce seroma risk.

3. Delayed wound healing and dehiscence (5% to 30%): Associated with smoking, longer OR time, higher preoperative weight, and in bariatric surgery patients

4. Abdominal flap necrosis: More common when abdominoplasty is combined with liposuction

5. Infection (1% to 7%): Risk is increased with smoking and combined procedures due to longer operative time. Only perioperative antibiotics are indicated.

6. Hematoma (1% to 10%): Drain promptly to avoid flap compromise or infection.

7. Umbilical necrosis: Usually wounds are allowed to heal secondarily.

8. DVT and PE (1%): Of all common plastic surgery operations, abdominoplasty carries the highest risk. Risk increases when BMI > 30, when there is >1,500 g resection, in combined procedures with longer operative time, and with use of hormone therapy. Risk decreases with use of postoperative DVT prophylaxis.

A. Lower back

1. The medial/paraspinal lumbar perforators are fragile so avoid unnecessary undermining.

2. Belt lipectomy

a. Wedge of back and flank soft tissue is excised with abdominal tissue, leaving a circumferential scar above the iliac crest.

b. This procedure recreates waist contour, tightens the back, and provides gentle upward pull of buttocks.

B. Thigh lift

1. Surgical excision is indicated in patients with skin redundancy and poor skin quality who therefore are not candidates for liposuction.

2. Anatomy

a. The medial thigh consists of thin dermis and two layers of underlying adipose tissue with superficial fascia dividing them.

b. *Colles’ fascia of the perineum

i. Contiguous with Scarpa fascia of the abdomen

ii. Fixed through attachments to the ischiopubic rami

iii. Strongest at junction of perineum and medial thigh

iv. Lies at deepest lateral-most aspect of vulvar soft tissue near origin of adductor muscles.

c. Proximally the posterior thigh has more soft tissue mobility, whereas the distal thigh demonstrates less mobility.

3. Examination

a. Assess skin, including striae, turgor, and elasticity

b. Identify the location of the skin redundancy and laxity; proximal versus distal, and medial versus lateral

4. Surgical approach

a. Upper one-third thigh laxity

i. Utilizes a groin crease incision and provides a predominately vertical pull

ii. *The closure must be anchored to Colles’ fascia in perineum for lasting results.

iii. Lack of anchoring can lead to

a) Inferior migration and widening of scars

b) Lateral traction deformity of the vulva

c) Early recurrence of ptosis

b. Upper and lower thigh laxity

i. With significant adiposity and ptosis, consider liposuction first and waiting 6 months to perform medial thigh lift.

ii. Significant ptosis requires a longitudinal incision along the length of the medial thigh, achieving circumferential tightening of the soft tissues.

iii. In some MWL patients, both vertical and horizontal components (L-shaped incision) are needed.

iv. Avoid incisions that cross the knee joint.

C. Buttocks

1. Indications for surgical intervention include buttock ptosis, poor skin quality, and loss of projection.

2. After massive weight loss, the buttock deformity is characterized by ptosis of excess skin and fat with simultaneous loss of projection.

3. Simply using a vertical vector of pull will result in blunted infragluteal fold, which only worsens buttock appearance.

4. Surgical approach

a. Buttock auto-augmentation. In this approach, the excess soft tissue is utilized to augment the projection of the buttocks while simultaneously correcting buttock ptosis and removing dermatolipodystrophy.

b. A robust blood supply from the superior and inferior gluteal perforators allows for various dermofascial, adipofascial, and adjacent tissue rearrangement techniques.

1. Includes an abdominoplasty, buttock lift, and (lateral) thighplasty.

2. Patients with abundant subcutaneous fat as well as ptosis and skin laxity are best approached in a staged fashion with liposuction followed by lower body lift 3 to 6 months later.

3. Surgical techniques

a. There are multiple techniques to perform lower body lift, but often the operation begins in a prone position.

b. Skin flaps are elevated just above the muscle fascia, preserving subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascia in the elevated flap.

c. Flaps are also raised in the gluteal region for buttock lift (stay superficial to gluteal vessels) and the greater trochanteric area (release bands of adherence) to assist with lateral thigh lift.

d. Circumferential cannula undermining without suction can be performed in the thighs to loosen fascial attachments with minimal collateral injury.

e. Excess skin and fat are resected. The superficial fascia (part of SFS) is reapproximated with permanent sutures. Suction drainage is required.

f. The patient is turned supine and the abdominoplasty is performed

VII. BRACHIOPLASTY

A. Goals of surgery

1. Resect upper arm dermatolipodystrophy

2. Elevate of the axillary fold

3. Optimize of scar placement

4. Avoid over-resection

B. Anatomy

1. Fascia

a. The axillary fascia comprises the floor of the axilla. The axillary vein and medial brachial cutaneous nerve are located just deep to this fascia.

b. The superficial fascia of the arm is part of the SFS.

2. Nerves

a. The medial brachial cutaneous nerve provides sensation to the medial upper arm and travels posterior to the basilic vein.

b. *The medial antebrachial cutaneous (MABC) nerve runs with or just anterior to the basilic vein and becomes superficial to the fascia about 14 cm (8 to 21 cm) proximal to the medial epicondyle. *It is the most commonly injured nerve in brachioplasty.

3. Lymphatics

a. Upper extremity lymph drains within networks around the basilic and cephalic veins and into the axillary nodal basin.

b. During brachioplasty, many of these lymphatics are disrupted, and therefore, the patient requires continuous compression wraps for several weeks after surgery

C. Preoperative evaluation

1. The amount of excess adipose and ptosis is gauged

2. The patient is examined with arms in the “victory position” (arms abducted 90° at shoulders, flexed 90° at elbows). Excess tissue is evaluated by pinching.

3. Assess skin quality for striae, elasticity, and thickness

D. Surgical techniques

1. Liposuction

a. Indicated for minimal excess adiposity and good skin quality

b. *Liposuction in the bicipital groove has a high risk of resultant contour abnormalities.

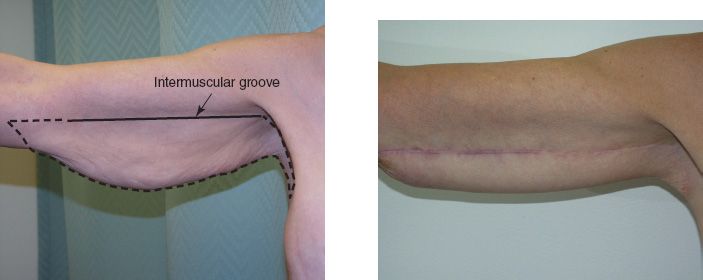

2. Excision (Fig. 33.4)

a. The incision is made either along the bicipital groove or over the posterior arm

i. Continuing the incision into the axilla allows for removal of redundant axillary and chest wall tissue.

Figure 33-4. Brachioplasty technique. Example of preoperative brachioplasty markings (left) and postoperative result (right).

ii. Attempt to limit incisions distal to the elbow

iii. Often, a Z- or W-plasty can help improve contour at the end of the incision

b. Minimize undermining of skin flaps to preserve vascularity

c. Identify and protect the MABC nerve and branches

d. Closure and post-op

i. Fascial suspension provides lasting results. The superficial fascia of the arm is anchored to the axillary fascia or the fascia of anterior axillary fold.

ii. In patients with significant laxity, some surgeons will plicate the triceps fascia to the biceps fascia

iii. Use of closed-suction drains is common, especially when skin flaps are undermined.

iv. Compression garments for comfort and edema control.

E. Complications

1. The overall complication rate is 20% to 25%. Approximately 15% of patients seek revision surgery.

2. Dehiscence is the most common complication and is more frequent when excision is combined with liposuction.

3. Hypertrophic scarring

4. Seroma

5. Nerve injury (most often neuropraxia; up to 5% permanent risk)

6. Lymphedema and lymphocele (higher rate with use of UAL)

VIII. UPPER BODY LIFT

A. Refers to excision of redundant skin and fat from the upper back.

B. The term is also often used to describe a combined approach that addresses adjoining areas of skin laxity and may involve a mastopexy, brachioplasty, and upper back lift in one surgery.

C. With the MWL patient, there is often characteristic descent of the lateral inframammary creases and concurrent overhang of thoracic skin folds.

D. Serves to excise excess tissue and reposition the inframammary creases.

E. Surgical approach

1. For mild upper back skin laxity, a transverse incision is made along the “bra line” and the skin folds are excised.

2. When also performing brachioplasty, the axillary incision can be extended inferiorly to tighten the upper back.

3. For moderate-to-severe cases, incisions must be carefully planned to account for significant horizontal and vertical laxity. However, be wary of skin flap compromise, especially with the lateral breast flap when mastopexy is performed simultaneously.

a. Horizontal laxity is addressed by extending the brachioplasty incision inferiorly. This may be curved around the lateral breast and connected to the inframammary mastopexy incision.

b. Vertical laxity requires a transverse incision, which may also be connected to the inframammary mastopexy incision

PEARLS

1. For all body contouring procedures, proper SFS approximation is a key in providing strength, reducing tension on the closure, and optimizing outcomes

2. Longer operative time, especially during abdominoplasty and combined procedures, increases the risk of thombotic events—use prophylactic perioperative anticoagulation for patients in need of multiple procedures

3. Active smoking results in a significant increase in infections and wound healing complications and is a contraindication to these contouring procedures

QUESTIONS YOU WILL BE ASKED

1. What is the mechanism for cellulite development?

The development of cellulite is due to the architectural changes of the superficial tissues. Cellulite fat is no different than subcutaneous fat elsewhere in the body. Superficial fat is separated into small compartments by multiple dense vertical septa. As the fat hypertrophies with weight gain or as skin relaxes with aging, the unyielding septa do not change, and this discrepancy leads to a dimpled appearance on the skin surface.

2. Will fat cells multiply with weight gain after removal (e.g., liposuction)?

Fat cells multiple in utero through childhood and adolescence. Once a person is mature, fat cells do not replicate; with weight gain, existing fat cells hypertrophy to accommodate the increase in fat stores. However, in the unique setting of morbid obesity, fat cells may once again divide.

3. How do you prevent vulvar distortion during a medial thigh lift?

During closure, anchor the thigh flaps to the deep layer of the superficial perineal fascia (Colles’ fascia).

4. How do you determine if a patient needs excision as opposed to liposuction?

Skin quality. Liposuction will remove the subcutaneous fat but will not address issues with the skin (e.g., severe skin excess, thin skin, skin with low elasticity, sun-damaged skin). Therefore, with poor skin quality, the skin will not conform after liposuction and the cosmetic appearance will be worse after surgery. For these patients, it is better to perform a skin resection operation.

5. What is superficial fascia system and its significance?

It is the layer of horizontal connective tissue with associated vertical and oblique investing septa. Informally, it is the layer fascia found throughout the subcutaneous level in all areas of the body contiguous with Scarpa fascia.

6. Why did I ask this woman about a history of breast cancer if she is here for an abdominoplasty consultation?

A common donor site for autologous breast reconstruction is the abdominal tissues. Abdominal-based breast reconstruction is precluded after abdominoplasty or panniculectomy because the perforators supplying the abdominal skin and fat are transected during these procedures.

Recommended Readings

Ahmad J, Eaves FF 3rd, Rohrich RJ, Kenkel JM. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) survey: current trends in liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(2):214-224. PMID: 21317119.

Berry MG, Davies D. Liposuction: a review of principles and techniques. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(8):985–992. PMID: 21168378.

Buck DW 2nd, Mustoe TA. An evidence-based approach to abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):2189–2195. PMID: 21124160.

El Khatib HA. Classification of brachial ptosis: strategy for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(4):1337–1342. PMID: 17496609.

Hurwitz DJ. Medial thighplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2005;25(2):180–191. PMID: 19338811.

Knoetgen J 3rd, Moran SL. Long-term outcomes and complications associated with brachioplasty: a retrospective review and cadaveric study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2219–2223. PMID: 16772920.

Richter DF, Stoff A, Velasco-Laguardia FJ, Reichenberger MA. Circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35(1):53–71; discussion 93. PMID: 18061798.

Soliman S, Rotemberg SC, Pace D, et al. Upper body lift. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35(1):107–114. PMID: 18061803.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>