Body ART: Introduction

|

Definitions

Body art is art made on, with, or consisting of, the human body. The most common forms of body art are tattoos, body piercings, and body painting, but other types include scarification, branding, tongue splitting, subdermal and extraocular implants. Tattooing is the practice of producing an indelible mark or figure on the human body by inserting pigment under the skin using needles or other sharp instruments.1 Body piercing refers to the cosmetic piercing of body parts for the implantation of objects such as rings, studs, or pins.2 Body painting is the application of paint on to the skin and includes face painting, the application of mehndi and temporary tattoos. Scarification is a means of permanently marking the skin by cutting alone, without the use of pigments. This includes the deliberate formation of keloids. When purposeful third-degree burns are used to induce a scar, the procedure is called branding.3 Tongue splitting is the bisection of the tongue from the tip toward the back for about 3–5 cm leading to an appearance similar to the tongue of a lizard.4,5 Subdermal implantation is the placing of a foreign body under the skin so that none of the object remains outside of the body. A three-dimensional effect is seen on the surface. Materials used are silicone, Teflon, or metal.6

Extraocular implantation is the placing of sterile nonpyrogenic platinum jewelry inside the interpalpebral conjunctiva of the eye.7

Tattooing

The word “tattoo” is said to come from Captain Cook after he saw markings on the bodies of the Polynesian people during his 1769 South Pacific voyage. “Ta-Tu” means “to mark” in Tahitian and is associated with the sound made by the Tahitian tattoo instrument.8 However, tattoos have probably been performed since the beginning of humanity. The famous Ice Man dating from 3300 BC found in the mountains of Europe was covered in tattoos, and they are seen on Egyptian mummies dating from 2000 BC. Tattoos were a sign of nobility, bravery and beauty. They are forbidden in the Old Testament in both Leviticus and Deuteronomy and in the Koran. Despite this, the practice has persisted and has been popular in Europe and America. During the Depression, the prevalence of tattooing declined as incomes shrank. Nondecorative tattoos were used to identify slaves, criminals and internees in prisoner of war and concentration camps during the Second World War. Military personnel often had tattoos with patriotic designs, together with hearts and the names of loved ones. With the advent of peace, the popularity of tattoos decreased, although they were still seen in close-knit group situations. They became associated with marginalized groups, signaling time spent in jail, “punk” status, membership in a motorcycle gang or a traveling circus. In recent times, images have become increasingly eclectic and the practice has become mainstream.9

Studies performed in 2008,10 2006,11 and 200412 found that 14% of 18- to 64-year-olds in the United States have tattoos, including approximately 30% of those under the age of 40. They are equally common among men and women and are seen in all ethnic groups. They are still found more commonly in those with a military association and in those of low educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. They are associated with the abuse of alcohol, the taking of illicit drugs and having spent significant time in prison.13 They are inversely associated with having a religious affiliation and having never drunk alcohol. Most tattoos are done in a dedicated studio, but approximately a quarter of people with tattoos have had at least one tattoo done elsewhere.

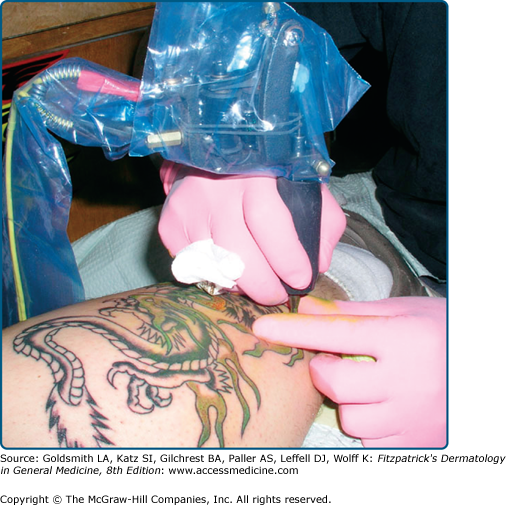

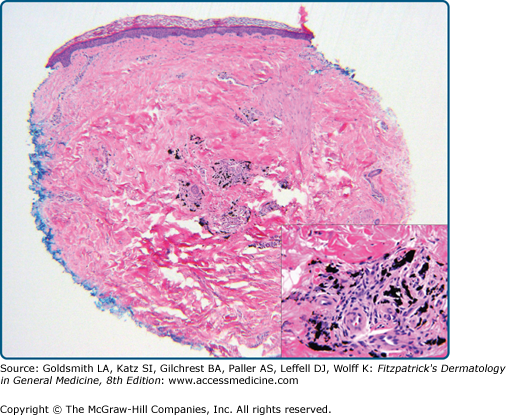

A handheld device, powered by low-voltage direct current, holds solid needles placed singly or in groups of up to fourteen on an oscillating bar (Fig. 101-1). The needles are dipped into colored inks and then moved across the skin in the desired pattern, penetrating rapidly and vertically 0.5–2.0 mm into the skin, depositing the pigment into the dermis. A thin layer of petroleum jelly is applied to the skin prior to and during the procedure to minimize blood loss and prevent spatter. After the tattoo is finished, the area is cleaned with a mixture of alcohol and water, and more ointment is applied. Sometimes, the ink is spread over an area of skin and the needles made to penetrate through it to carry the particles into the skin. Amateur tattooers often do it this way using handheld needles wound round with thread to prevent too deep penetration. Other instruments used may be pencils, pens, and straight pins. Much of the pigment is extruded through the epidermis during the first 10 days (Fig. 101-2). The final location of the pigment is in the mid-to-lower dermis (Fig. 101-3), but the pigment in amateur tattoos tends to be more superficially and more variably placed. The particles are membrane bound (in secondary lysosomes) within fibroblasts, macrophages and occasionally mast cells around blood vessels. They may also be seen around hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Many of the pigment conglomerations are too large to traverse the vessel walls and leave the area of original deposition, but with time pigment diffusion from the site may lead to blurring of the visible design as well as pigment deposition in the draining lymph nodes (Fig. 101-4).14,15

Tattoo pigment composition, as obtained from the manufacturer, and possibly further mixed by the artist, is complex, usually nonsterile, unregulated, variable and changing. In recent times, industrial organic pigments, including azo and polycyclic compounds, sandalwood and brazilwood, as well as aluminum, cadmium, calcium, copper, iron, phosphorus, silica, and sulfur have been identified.16 In addition, titanium dioxide and barium sulfate are often used to lighten the color. The 1976 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act limited the content of lead and mercury in cosmetics for application to the skin so that now these two elements are rarely found.17–19 The pigment in amateur tattoos is usually black and carbon based, often deriving from India ink, charcoal, soot, or mascara20 (Table 101-1).

Red Mercuric sulfide (cinnabar); cadmium selenide; ferric hydrate (sienna); sandalwood; brazilwood; aromatic azo compounds including naphthol-AS; quinacridone |

Green Chromium oxide; lead chromate; copper or aluminum phthalocyanine; malachite (contains copper); ferrocyanides and ferricyanides |

Purple Manganese ammonium pyrophosphate; aluminum salts; quinacridone; dioxazine/carbazole |

Blue Cobalt aluminum oxide; chromium oxide; copper phthalocyanine |

Yellow Cadmium sulfide; curcuma (from the ginger plant family); chrome yellow (lead chromate mixed with lead sulfide) |

Black India ink; ferrous oxide; magnetite (Fe3O4); carbon; logwood (a heartwood extract from Haematoxylum campechianum found in Central America and the West Indies) |

Brown Iron oxides |

White Zinc oxide; titanium dioxide; lead carbonate; barium sulfate |

Medical complications are unusual in developed countries. Clearly, there is a real risk of contracting a contagious disease, but most recent reports are anecdotal. These include reports of verrucae, molluscum contagiosum, and atypical mycobacterial infections in the area of the tattoo, methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections spreading from the area of the tattoo and bacterial endocarditis within a week of tattoo application.21–26 There has been more than one report of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a tattoo site among HIV-infected individuals with visceral leishmaniasis.27 Inoculation leprosy is common in parts of the world where leprosy is endemic.28,29 (See Table 101-2.)

Bacterial

| Viral

|

There have been outbreaks of hepatitis B traced to tattoo parlors in the past, but currently there is a controversy as to how often hepatitis C in the United States is transmitted this way. During the same time that the prevalence of tattoos has increased, the absolute numbers of reported acute hepatitis B and C cases have fallen. The numbers were at a nadir for hepatitis B in 2007 (1.5/100,000), in contrast to a high of 11.5/100,000 in 1985; for hepatitis C, the numbers are stable at 0.3/100,000 since 2003, from a high of 2.4/100,000 in 1992.30 Most hepatitis C infection is asymptomatic. The sources of approximately 65% of the cases of hepatitis C are unidentified. Cross-sectional data from a number of population groups, for example, veterans,31 attendees in an orthopedic practice,32 hospital outpatients,33 have been inconsistent in identifying tattoos as an independent risk factor for the presence of Hepatitis C. Variables such as getting the procedure in a dedicated studio or in a penitentiary34,35 may be relevant and the confusion may relate to the fact that, in some people, tattoos are a marker for other unconventional or socially disapproved behaviors.36,37 The American Association of Blood Banks recommends that blood for donation not be taken from anyone within a year of a tattoo or a body piercing, unless applied by a state-regulated entity with sterile needles and ink that have not been reused.38 In 2005, the Canadian Blood Services decreased the deferral period from 12 to 6 months. Donor deferral rates were assessed before and after the change. Remote tattooing was associated with increased hepatitis C risk, but this did not hold true for recent tattooing nor piercing. There was no measurable adverse effect on safety and a positive but less than expected effect on blood availability.39

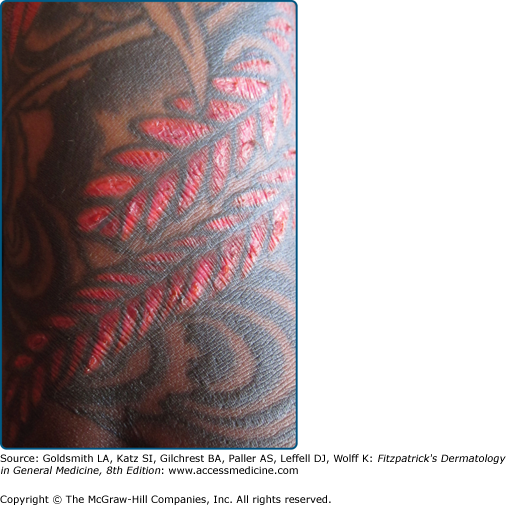

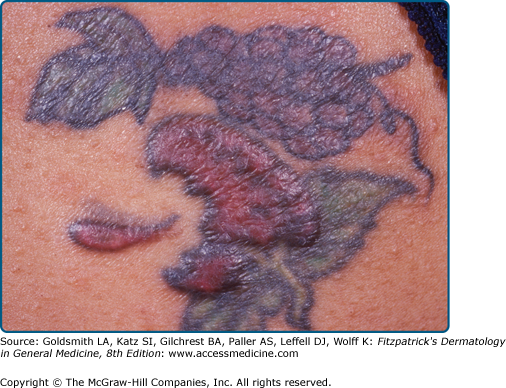

Many, but not all, of the pigment-based reactions are in the red areas of tattoos (Fig. 101-5). Now that cinnabar, vermilion or other pigments containing mercuric sulfide, are rarely used, other culprits have been identified. These include cadmium selenide and quinacridone.40 Reactions may be photosensitive and histology may be pseudolymphomatous, lichenoid,41 or granulomatous, either (1) foreign body type with numerous giant cells containing pigment or (2) hypersensitivity type with dense aggregates of epithelioid cells, a thin peripheral ring of lymphocytes and few giant cells.42 Hypersensitivity reactions may be localized or generalized,43 but standard epicutaneous patch testing is not often helpful, presumably related to the dermal placement or the rapid decomposition of the tattoo antigen.44 The social implications of tattooing are protean and may alert the onlooker to other risk-taking behaviors.45

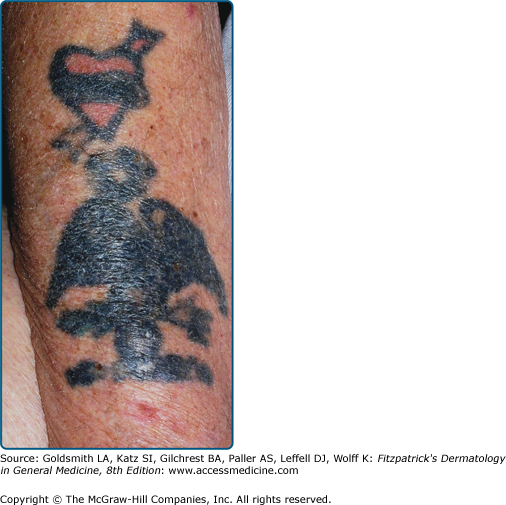

Most people are proud of their tattoos, but approximately 17% desire removal. In addition, 5% opt for and 8% are considering further tattooing to cover a disliked or faded image. Often these people have obtained their tattoos at a young age and want them removed or changed to enhance self-esteem, or for social, domestic, and family reasons.46,47 Many tattoo removal methods have been documented (Table 101-3), but most are only partially effective, and leave scarring and pigmentary changes (Fig. 101-6). With the advent of the theory of thermal relaxation, lasers with very short (nanosecond) high-energy pulses have been designed, which are less likely to heat the surrounding tissue leaving scars (Table 101-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree