Keywords

Biosimilar, Inflectra, Remsima, CT-P13, Infliximab-dyyb

Key points

- •

Through the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation act, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined a biosimilar as a biologic product that is highly similar to the original product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components.

- •

Preclinical analytical assessments are used to determine variations in biosimilar agents and are critical for their approval.

- •

Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb, CT-P13), a recently approved biosimilar by the FDA, is indicated in patients with chronic severe psoriasis when other systemic therapies are medically less appropriate.

Introduction

The development of biosimilar agents such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors has significant potential to change the standards of psoriasis therapy in forthcoming years. The availability of biologic drugs for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis has revolutionized psoriasis treatment, and, as the patents for these medications (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab) are expiring soon, dermatologists can expect increased advocacy for biosimilars.

The development of biosimilars is not the same as developing a generic, in part because biologics are so much more complex than small molecule drugs. Biologics are so complex that no company can duplicate them, not even the originator company. Each batch of an innovator biologic may differ in small ways from other batches. Variation within an innovator product occurs and is acceptable as long as it is not thought to have clinical implications. Similarly, biosimilars are not identical to the innovator product but can be marketed if the differences between the biosimilar and the innovator are sufficiently small that no clinical implications are expected. An extensive array of data is required to demonstrate biosimilarity (more data than are required of batch-to-batch variants in the innovator product).

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BCPI) act was created as a part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 as an abbreviated licensure pathway for biologic products that were “biosimilar” to, or interchangeable with, the original biologic product. Through the BCPI act, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined a biosimilar as a biologic product that is highly similar to the original product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components. No clinically meaningful differences between the biologic and the biosimilar in terms of safety, purity, and potency can exist. These aspects of the biosimilar drug must be demonstrated through analytical studies, animal studies, and at least 1 clinical study, unless the FDA deems it unnecessary. The biosimilar, however, does not need to demonstrate its independent efficacy and safety for FDA approval, as is typically required for the original biologic off which it is modeled.

The greatest potential for biosimilar agents in the treatment of psoriasis is in association with TNF inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab); however, many clinical trials investigating these biosimilar agents are currently in the preliminary stages and results have yet to be published. An infliximab biosimilar by the brand name of Inflectra was recently approved in April 2016 by the FDA for the treatment of adult severe plaque psoriasis, adult and pediatric moderately-to-severely active Crohn disease unresponsive to conventional therapy, moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in combination with methotrexate, active ankylosing spondylitis, and active psoriatic arthritis.

Small molecule generic drugs

In approving a generic drug, the FDA requires pharmaceutical equivalence to the reference drug (identical amounts of same active drug ingredient in the same dosage form and route of administration), bioequivalence to the reference drug, and adequate labeling and manufacturing. Bioequivalence is generally used to establish similarity between a generic drug and reference drug and is defined as the absence of significant differences in the availability of the active ingredient at the site of drug action. Two drugs are bioequivalent if the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of pharmacokinetic parameters (maximum concentration, area under the curve) of generic-to-reference drug ratios fall within 80% to 125%. This bioequivalence ensures that the rate and extent of absorption of the generic drug does not differ from the reference drug.

Generic drugs approved by the FDA have the same high-quality, strength, purity, and stability as the reference drug. In addition, the generic manufacturing, packaging, and testing sites must pass the same quality standards as those of brand name drugs.

Creation of the biosimilar and analytical assessments

The creation of original biologic agents takes place in unique genetically bioengineered cell lines. Companies that produce biosimilar agents do not have access to these specific cell lines and thus use new cell lines to produce biosimilars. This, in addition to the other multiple steps involved in production, induces variations in the biosimilar from the original reference biologic agent, which are determined in preclinical analytical assessments.

The process of creating the biosimilar involves recombinant DNA that encodes the exact same amino acid sequence as the originator biologic. This recombinant DNA is placed within a plasmid and transfected into a new cell line in order to produce the biosimilar protein product, which is then collected and purified. This entire process is tightly optimized and monitored to minimize variation from the reference biologic.

In comparison to the creation of generic small molecule drugs, which are produced by chemical synthesis, the creation of biosimilars occurs within living cells and can involve quaternary folding of structures. Glycosylation, folding, charge, the presence of impurities, and individual amino acid variants can differ and potentially alter the function of the protein product. In addition, biosimilars can undergo physical and chemical degradation such as deamidation, cleavage, and aggregation; these changes can make a molecule more likely to be recognized by the body as foreign ( Table 14.1 ).

| Small molecule drug | Biologic agent |

|

|

| Generic small molecule drug | Biosimilar agent |

|

|

Preclinical analytical assessments are used to determine these variations and are critical for approval of these biosimilar agents. There are approximately 40 different analytical methods that are used to assess approximately 100 various drug attributes.

Drug companies are required by the FDA to provide information on any manufacturing changes as well as bioanalytical data characterizing each drug batch. Posttranslational modifications are evaluated using mass spectrometry, assessing for glycosylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, sulfation, glycation, and charge. If minor changes do exist, however, the FDA does not necessarily mandate clinical studies to re-evaluate efficacy.

In addition, functional assays are necessary to compare the biosimilar agent to the biologic agent. Functional assays includes the evaluation of drug binding affinity and avidity to the target and ability to neutralize target cytokines. End product assessments include evaluation of impurities, aggregates, product stability (shelf-life and temperature alterations), and product devices for delivery (autoinjectors and prefilled syringes).

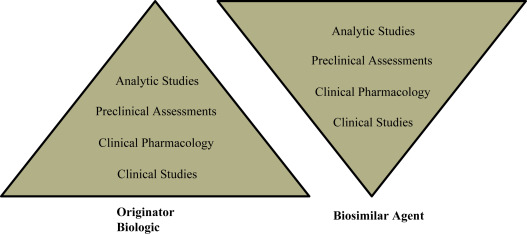

Regulation

Given the increased complexity in developing biosimilars as compared with generic molecules, they are susceptible to more stringent regulatory pathways to maintain the quality and safety of the drug. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) was the first organization to develop and publish guidelines for biosimilars development, and the FDA has released 7 guidances for the development of biosimilars at present. The FDA recommends a stepwise totality-of-the-evidence approach in assessing biosimilarity demonstration ( Fig. 14.1 ). Both agencies require the primary amino acid sequence, potency, dose, and route of administration of the biosimilar and biologic product to be identical, and any differences in higher-order structure and posttranslational modifications must be minimal and cannot impact safety, efficacy, or immunogenicity. In order to demonstrate biosimilarity, 1 phase I trial for pharmacokinetics or a single pivotal phase 3 trial is required for FDA approval.

Biosimilar companies have argued that clinical studies should not be required to be repeated with each manufacturing change, especially if companies producing biologics are not required to. The inability to exactly replicate each batch of drug is true for the reference biologic agents as well as for the biosimilars. For example, Schiestl and colleagues analyzed the biochemical fingerprint of etanercept and found that it varied by 20% to 40% in basic variants and degree of glycosylation.

Although the biosimilar regulation pathway differs between various regions of the world, the guidelines for approval and licensing are similar between main organizations (EMA, FDA, and World Health Organization). The stringent analyses of structural and functional components of a biosimilar will help assure quality, efficacy, and safety of this novel therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree