Biology of Hair Follicles: Introduction

|

Evolution and Function of Hair

Hair is found only in mammals, where during the course of evolution its primary roles were to serve as insulation and protection from the elements. However, in contemporary humans, hair’s main purpose revolves around its profound role in social interactions. Loss of hair (alopecia) and excessive hair growth in unwanted areas (hirsutism and hypertrichosis) can lead to significant psychological and emotional distress that supports a multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical and cosmetic effort to reverse these conditions.

Fundamental understanding of hair growth and its controls is increasing and result in new treatments for alopecia.1,2 These advances resulted from the interest of developmental biologists and other investigators in the hair follicle as a model for a wide range of biologic processes. As each hair follicle cyclically regenerates, it recapitulates its initial development. Many growth factors and receptors important during hair follicle development also regulate hair follicle cycling.3–10 The hair follicle possesses keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells (MSCs), nerves, and vasculature that are important in healthy and diseased skin.11–13 To appreciate this emerging information and to properly assess a patient with hair loss or excess hair (see Chapter 88), an understanding of the anatomy and development of the hair follicle is essential.

Embryology

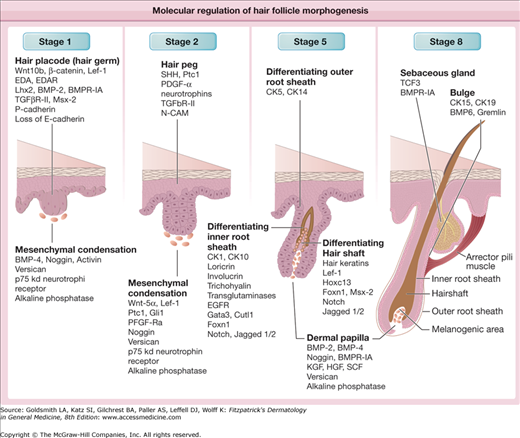

Morphologically, hair follicle development has been divided into eight consecutive stages, several of which are illustrated in Fig. 86-1. Each stage is characterized by unique expression patterns for growth factors and their receptors, growth factor antagonists, adhesion molecules, and intracellular signal transduction components.14–16 Promising advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms behind hair follicle development arose through the discovery that mammalian counterparts (homologs) of genes important for normal Drosophila (fruit fly) development also affect hair follicle development. Decapentaplegic [Dpp/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)], Engrailed (en), Homeobox (hox), hedgehog/patched (hh/ptc), notch, wingless/armadillo (wg/wnt/catenin) genes are all critical for hair follicle and vertebrate development in general.17–19 These genes were all first discovered in Drosophila, thus, most of the names assigned to them describe the peculiar appearance (phenotype) of the flies carrying mutations in these genes.20

Figure 86-1

Molecular regulation of hair follicle morphogenesis. The scheme shows the expression of different growth factors, their receptors, adhesion, and cell matrix molecules, transcriptional regulators in hair follicle epithelium, and mesenchyme during distinct stages of hair follicle development. BMP = bone morphogenetic protein; BMPR-IA = bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA; CK = keratin 5; Cutl1 = cut-like 1; E-cadherin = epithelial cadherin; EDA = ectodysplasin; EDAR = ectodysplasin receptor; EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; Foxn1 = forkhead box N1; Gata3 = GATA binding protein 3; Gli1 = glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1; HGF = hepatocyte growth factor; Hoxc13 = homeobox C13; KGF = keratinocyte growth factor; Lef-1 = lymphoid enhancer factor 1; Lhx2 = LIM homeobox 2; N-CAM = neural cell adhesion molecule; P-cadherin = placental cadherin; PDGF-α = platelet-derived growth factor α polypeptide; PFGF-Rα = platelet-derived growth factor receptor α; Ptc1 = patched1; SCF = stem cell factor; Shh = sonic hedgehog; TCF3 = transcription factor 3; TGF-βR-II = transforming growth factor-β receptor 2.

Follicle formation begins on the head, and then moves downward to the remainder of the body in utero. The first hairs formed are lanugo hairs, which are nonpigmented, soft, and fine. Lanugo hair is typically shed between the 32nd and 36th weeks, although approximately one-third of newborns still retain their lanugo hair for up to several weeks after birth.

Patterning genes, called homeobox genes, which are precisely organized in the genome so that they are expressed in strict temporal sequences and spatial patterns during development, likely are responsible for the nonrandom and symmetric distribution of hair follicles over the body.21,22 In adult mice, homeobox gene expression reappears in hair follicles and serves to maintain normal hair shaft production.6 Engrailed, a type of homeobox gene, is responsible for dorsal–ventral patterning, and mice lacking engrailed develop hair follicles on their footpads.23

Although hair follicles and hairs all share the same basic anatomy, their growth, size, shape, pigmentation, and other characteristics differ widely, based on body location and variation among individuals. Many of these characteristics are established during development but are then profoundly altered by hormonal influences later in life. We are beginning to understand the genes controlling hair length, curl and distribution because of elegant genetic studies on dogs. These studies reveal that fibroblast growth factor-5 (FGF-5), Keratin 71, and R-spondin 2 influence length, curl and distribution respectively.24 In humans, thicker hair found in Asians is associated with increased activity of ectodysplasin receptor (EDAR),25 the receptor of ectodysplasin (EDA) (see below).

The size of many types of follicles changes drastically several times throughout life. For example, lanugo hair follicles, which produce hair shafts several centimeters long, convert to vellus follicles that produce small hairs that protrude only slightly from the skin surface. Later in life, vellus follicles on the male beard enlarge into terminal follicles that generate thick, long hairs. On the scalp of genetically predisposed individuals, terminal follicles miniaturize and form effete, microscopic hairs.

In the human fetus, hair follicles develop from small collections of cells, called epithelial placodes, which correspond to stage 1 of hair follicle development and first appear around 10 weeks’ gestation (see Fig. 86-1). The epithelial placode then expands to form the “primary hair germ” whose progeny eventually generate the entire epithelial portion of the hair follicle.26

The cells of the hair placode and germ express placental cadherin and become oriented vertically, losing their desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and epithelial cadherin, which decreases their adhesion to their neighbors.27–29 Dermal cells beneath the hair placode form a cluster (or condensate), which later develops into the dermal papilla.30

Hair follicle formation depends on a series of mesenchymal/epithelial interactions.30 An initial signal arises in the mesenchyme (primitive dermis) and instructs the overlying epithelium to form an appendage, indicated by the appearance of regularly spaced placodes (see Fig. 86-1). The second signal arises from the epithelial placode and causes an aggregation of cells in the underlying mesenchyme that will eventually form the dermal papilla. Finally, a signal from this primitive dermal papilla initiates proliferation and differentiation of placode cells, ultimately leading to formation of a mature follicle. These reciprocal signals pass through the intervening basement membrane, which undergoes alterations in its morphology and chemical composition that may alter its ability to sequester growth factors and binding proteins, thus possibly modulating the epithelial/mesenchymal interactions.

Many of these regulatory molecules important for the formation of the hair follicle have been defined, but how they interact to generate hair follicles in an otherwise homogeneous epithelium is yet to be determined. In one model, the spacing and size of placodes are regulated by a dermal signal, which varies in character in different body regions. The dermal signal occurs uniformly within each body region and triggers the activation of promoters and repressors of follicle fate in the epithelium that then compete with one another, resulting in the establishment of a regular array of follicles.15,31 Differences in the levels of promoter and repressor activation could account for regional differences in the size and spacing of follicles. Consistent with this model, several positive and negative regulators of hair follicle fate are initially expressed uniformly in the epidermis and subsequently become localized to placodes.

One of the earliest molecular pathways that positively regulates hair follicle initiation is the WNT/β-catenin pathway. β-Catenin is the downstream mediator of WNT signaling. WNT proteins bind to receptors on the cell membrane and, through a series of signals, inhibit the degradation of cytoplasmic β-catenin. β-Catenin then translocates to the nucleus, forming a complex with the LEF/TCF family of transcription factors and resulting in expression of downstream genes.15,31 Activation of this β-catenin pathway appears necessary for establishing epithelial competence—a state in which the epithelial tissue has the potential to form a hair follicle. Normally, the β-catenin pathway is inactive in the adult epidermis, but by artificially activating β-catenin in epidermal basal cells of adult transgenic mice, hair follicles develop de novo.32 This remarkable finding could eventually have therapeutic implications, although constant activation of this pathway in the hair follicle also results in pilomatricomas and trichofolliculomas, two types of relatively rare cutaneous tumors.32,33

EDA, a molecule related to tumor necrosis factor, and its receptor (EDAR) also are part of another major pathway that stimulates early follicle development in both mice and humans.34 EDA gene mutations cause X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, a syndrome associated with decreased numbers of hair follicles, and defects of the teeth and sweat glands (see Chapter 142).35 The EDAR gene is mutated in autosomal recessive and dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasias, causing identical phenotypes to those resulting from EDA mutations. The mouse Edar gene is expressed ubiquitously in the epithelium before placode formation, and then becomes restricted to placodes, whereas the Eda gene is ubiquitously expressed even after placode formation.36 Mice with mutations in these genes have the same phenotype as humans with similar mutations, and mice overexpressing Eda in the epidermis show formation of the “fused” follicles due to the loss of proper spacing between neighboring hair placodes.37,38 Humans with more active EDAR genes have thicker hair.25

In contrast to EDA and EDAR, which promote hair follicle development, members of the BMP family inhibit follicle formation. Bmp2 is expressed diffusely in the ectoderm, but then localizes to the early placode and underlying mesenchyme, while Bmp4 is expressed in the early dermal condensate.39,40 BMP signaling inhibits placode formation, whereas neutralization of BMP activity by its antagonist Noggin promotes placode fate, at least in part via positive regulation of lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (Lef-1) expression.39,41–43 Mice lacking Noggin have fewer hair follicles than normal and retarded follicular development.43 The Notch pathway also appears to play a role in determining the follicular pattern. The Notch ligand Δ-1 is normally expressed in the mesenchyme underlying the placode44–46 and, when misexpressed in a small part of the epithelium, promotes and accelerates placode formation while suppressing placode formation in surrounding cells.44,47

Another secreted protein present in the follicular placode that plays a major role in epithelial-mesenchymal signaling is sonic hedgehog (Shh).48,49 Skin from mice lacking Shh have extremely effete hair follicles with poorly developed dermal papillae.50–52 Patched1 (Ptc1), the receptor for Shh, is expressed in the germ cells and the underlying dermal papilla, suggesting that Shh may have both autocrine and paracrine inductive properties necessary for hair germ and dermal papilla formation.53 Patched is the gene deficient in basal cell nevus syndrome (see Chapter 116).19

In the next stage of development, the bulbous peg or hair bud (or stage 2 of hair follicle development, see Fig. 86-1) is formed by elongation of the hair germ into a cord of epithelial cells. The mesenchymal cells at the sides of the peg will develop into the fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, and those at the tip of the peg will develop into the dermal papilla. The deepest portion of the follicle peg forms a bulbous structure that surrounds the underlying mesenchymal cells destined to become the dermal papilla. These epithelial cells will become the matrix of the hair follicle, which gives rise to the hair shaft and inner root sheath. The outer root sheath forms two bulges on the side of the hair follicle forming an obtuse angle with the surface of the skin. The superficial bulge will develop into the sebaceous gland. The deeper bulge serves as the future site of epithelial stem cells that generate the new lower follicle during hair follicle cycling. The arrector pili muscle usually attaches in the bulge area, and contraction of the muscle causes a more vertical orientation of the hair shaft leading to “goose bumps.” In the axillae, anogenital region, areolae, periumbilical region, eyelids (the specialized glands of Moll), and external ear canals, a third bulge develops superficial to the sebaceous gland bud and gives rise to the apocrine gland.

As the hair follicle bulb appears during the bulbous peg stage, at least eight different cell layers constituting all of the components of the mature hair follicle are formed. Understanding which genes determine specific cell lineages within the follicle is an important question. GATA-3 is important in inner root sheath differentiation.54 Notch1, a membrane protein involved in determining cell fate through cell–cell interactions and intracellular signal transduction, and its ligands Serrate1 and Serrate2 are expressed in matrix cells destined to form the inner root sheath and hair shaft.46,55 Notch1 appears to control the phenotype of keratinocytes as they leave the bulb matrix and differentiate into specific cell types.56

The central lumen where the hair shaft will emerge is formed by necrosis and cornification of epithelial cells in the infundibulum. As the hair shaft is produced, several signaling pathways are involved in the control of its differentiation. Wnt/β-catenin/Lef-1 signaling plays an important role in hair shaft formation, and ectopic expression of Wnt3 in the hair follicle outer root sheath causes hair shaft fragility.57,58 Hair shaft keratin genes contain binding sites for Lef-1,59 which translocates to the nucleus after activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway. WNT signaling probably regulates expression of hair shaft keratin genes, because nearly all of these genes contain Lef-1 binding sites in their promoter regions.60

BMP signaling is also essential for proper differentiation of the inner root sheath and hair shaft, because conditional deletion of BMP receptor type 1A in keratinocytes results in profound alterations of the inner root sheath and hair shaft formation.61–63 Several other putative transcription factors control hair shaft differentiation, including HOXC13,6 a homeobox protein, and the WHN gene,64–66 which is mutated in nude mice and rarely in humans with hair, nail, and immune defects.67,68

This process of hair follicle formation is repeated in several waves, with the formation of secondary follicles alongside the initial follicle. The follicles are primarily clustered into groups of three and possess an oblique orientation with a similar angle to their neighbors.

Anatomy

After formation of the lanugo hair that is characteristic of the prenatal period, there are two major types of hair classified according to size (Table 86-1). Terminal hairs are typically greater than 60 μm in diameter, possess a central medulla, and can grow to well over 100 cm in length. The duration of the growing stage (anagen) determines the length of the hair. The hair bulb of terminal hairs in anagen is located in the subcutaneous fat. In contrast, vellus hairs are typically less than 30 μm in diameter, do not possess a medulla, and are less than 2 cm in length. The hair bulb of vellus hairs in anagen is located in the reticular dermis. Terminal hairs are found on the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes at birth. Vellus hairs are found elsewhere, and, at puberty, vellus hair follicles in the genitalia, axillae, trunk, and beard area in men transform into terminal hair follicles under the influence of sex hormones. Terminal hair follicles in the scalp convert to vellus-like or miniaturized hair follicles during androgenetic alopecia (see Chapter 88).1,69

The curvature of the hair varies greatly among different individuals and races, and ranges from straight to tightly curled. Curved hair shafts arise from curved hair follicles. The shape of the inner root sheath is thought to determine the shape of the hair. Curled hair in cross section is more elliptical or flattened in comparison with straight hair, which is more round. Several genes influencing hair shape have been identified. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway and in insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 result in curly hair in mice.70,71

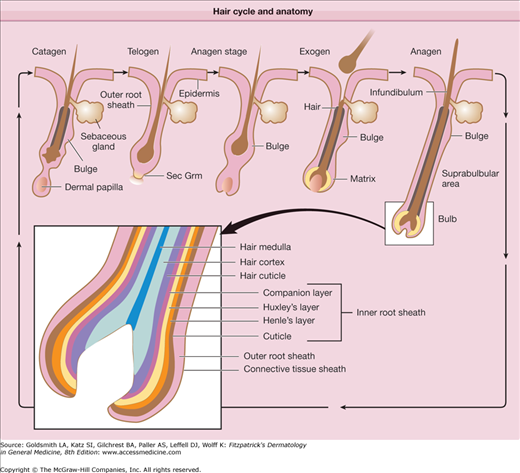

The upper follicle consists of the infundibulum and the isthmus, and the lower follicle consists of the suprabulbar and the bulbar areas (Fig. 86-2).14,66 The upper follicle is permanent, but the lower follicle regenerates with each hair follicle cycle. The major compartments of the hair from outermost to innermost include the connective tissue sheath, the outer root sheath, the inner root sheath, the cuticle, the hair shaft cortex, and the hair shaft medulla, each characterized by distinct expression of the hair follicle-specific keratins (Table 86-2).72,73

Figure 86-2

Hair cycle and anatomy. The hair follicle cycle consists of stages of rest (telogen), hair growth (anagen), follicle regression (catagen), and hair shedding (exogen). The entire lower epithelial structure is formed during anagen and regresses during catagen. The transient portion of the follicle consists of matrix cells in the bulb that generate seven different cell lineages, three in the hair shaft and four in the inner root sheath. B = bulge; E = epidermis; DP = dermal papilla; H = hair shaft; M = matrix; ORS = outer root sheath; S = sebaceous gland; Sec Grm = secondary germ.

HF Compartments | Type I Keratins, New Nomenclature (Old Nomenclature) | Type II Keratins, New Nomenclature (Old Nomenclature) |

|---|---|---|

Outer root sheath | K14 (K14), K15 (K15), K16 (K16), K17 (K17), K19 (K19) | K5 (K5) |

Inner root sheath, companion layer | K16 (K16), K17 (K17) | K75 (K6hf), K6 (K6) |

Hair matrix/precortex | K35 (Ha5) | K85 (Hb5) |

Inner root sheath, Henle’s layer | K25 (K25irs1), K27 (K25irs3), K28 (K25irs4) | K71 (K6irs1) |

Inner root sheath, Huxley’s layer | K25 (K25irs1), K27 (K25irs3), K28 (K25irs4) | K71 (K6irs1), K74 (K6irs4) |

Inner root sheath, cuticle | K25 (K25irs1), K26 (K25irs2), K27 (K25irs3), K28 (K25irs4) | K71 (K6irs1), K72 (K6irs2), K73 (K6irs3) |

Hair, cuticle | K32 (Ha2), K35 (Ha5) | K82 (Hb2), K85 (Hb5) |

Hair, mid-/upper cortex | K31 (Ha1), K33a (Ha3-I), K33b (Ha3-II), K34 (Ha4), K35 (Ha5), K36 (Ha6), K37 (Ha7), K38 (Ha8) | K81 (Hb1),a K83 (Hb3), K85 (Hb5), K86 (Hb6)a |

Hair, medulla | K16 (K16), K17 (K17), K25 (K25irs1), K27 (K25irs3), K28 (K25irs4), K33 (Ha3), K34 (Ha4), K37 (Ha7) | K5 (K5), K6 (K6), K75 (K6hf), K81 (Hb1)a |

The outer root sheath is continuous with the epidermis (see Fig. 86-2) at the infundibulum and continues down to the bulb. The cells of the outer root sheath change considerably throughout the follicle. The outer root sheath in the infundibulum resembles epidermis and forms a granular layer during its keratinization. In the isthmus, the outer root sheath cells keratinize in a trichilemmal fashion, lacking a granular layer. Trichilemmal keratinization occurs where the inner root sheath begins to slough. Desmoglein expression markedly changes here as well and trichilemmal or pilar cysts retain these characteristics.74 Keratinocytes in the outer root sheath form the bulge at the base of the isthmus (see Section “Hair Follicle Stem Cells”). These cells generally possess a higher nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio compared with other areas of the follicle. Moving downward, the outer root sheath cells become much larger and contain abundant glycogen in the suprabulbar follicle. In the bulb, the outer root sheath consists of only a single, flattened cell layer that can be traced to the base of the follicle.

The inner root sheath extends from the base of the bulb to the isthmus and contains four parts from outermost to innermost: companion layer, Henle layer, Huxley layer, and the inner root sheath cuticle. The companion layer (see Fig. 86-2) has been referred to as the innermost layer of the outer root sheath, but recent evidence indicates that it is more like inner root sheath than outer root sheath.75 The companion layer attaches to Henle layer and moves upward with the rest of the inner root sheath; thus, it provides a slippage plane between the outer root sheath, which is stationary, and the inner root sheath.76 The companion layer is prominent in some follicles (e.g., the beard) compared with others. The cells of the companion layer are flat compared to the cuboidal outer root sheath cells and express a type II cytokeratin, K6hf.75 Henle layer is one-cell-layer thick and is the first to develop keratohyalin granules and the first to keratinize. Huxley layer is two to four cell layers thick and keratinizes above Henle layer at the region known as Adamson fringe. Some cells within Huxley’s layer protrude through Henle layer and attach directly to the companion layer. These cells are called Fluegelzellen or wing cells.77 The cells of the inner root sheath cuticle partially overlap, forming a “shingled roof” appearance, and they intertwine precisely with the cuticle cells of the hair shaft. This association between the two cuticles anchors the hair shaft tightly to the follicle. The inner root sheath, composed of hard keratins and associated proteins (see Table 86-2), is thought to dictate hair shape by funneling the hair shaft cells as they are produced. The transcription factor, GATA-3, is critical for inner root sheath differentiation and lineage. Mice lacking this gene fail to form an inner root sheath.54

The hair shaft (and inner root sheath) arises from rapidly proliferating matrix keratinocytes in the bulb, which have one of the highest rates of proliferation in the body. The cells of the future hair shaft are positioned at the apex of the dermal papilla and form the medulla, cortex, and hair shaft cuticle (see Fig. 86-2). Immediately above the matrix cells, hair shaft cells begin to express specific hair shaft keratins in the prekeratogenous zone. The differentiation of hair shaft cells in this zone is dependent on the Lef-1 transcription factor. Lef-1 binding sites are present in most hair keratin genes. BMP receptor type 1a is also critical for matrix cell differentiation into the hair shaft, because loss of this receptor prevents hair shaft differentiation.61–63

The hair shaft cuticle covers the hair, and its integrity and properties greatly impact the appearance of the hair. Once the hair exits the scalp, the cuticle endures weathering, and it is often completely lost at the distal ends of long hairs. Inside the cuticle, the cortex comprises the bulk of the shaft and contains melanin. The cortex is arranged in large cable-like structures called macrofibrils. These, in turn, possess microfibrils that are composed of intermediate filaments. The medulla sits at the center of larger hairs, and specific keratins expressed in this layer of cells (see Table 86-2) are under the control of androgens.78

The dermal papilla (see Fig. 86-1) is a core of mesenchymally derived tissue enveloped by the matrix epithelium. It is comprised of fibroblasts, collagen bundles, a mucopolysaccharide-rich stroma, nerve fibers, and a single capillary loop. It is continuous with the perifollicular sheath (dermal sheath) of connective tissue that envelops the lower follicle.

Tissue recombination experiments have shown that the dermal papilla has powerful inductive properties, including the ability to induce hair follicle formation when transplanted below nonhair-bearing footpad epidermis.76,79 This shows that the tissue patterning established during the fetal period can be altered under appropriate conditions. In human follicle, the volume of the dermal papilla correlates with the number of matrix cells and the resulting size of the hair shaft.80 In mice, sizes of the hair bulb and hair diameter strongly depend of the proliferative activity of the matrix keratinocytes.81

Many soluble growth factors that appear to act in a paracrine manner on the overlying epithelial matrix cells originate from the dermal papilla. Specifically, keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) is produced by the anagen dermal papilla, and its receptor, FGF receptor 2 (FGFR2), is found predominantly in the matrix keratinocytes. Injections of KGF into nude mice produce striking hair growth at the site of injection,82 suggesting that KGF is perhaps necessary for hair growth and cycling. However, surprisingly, KGF knockout mice develop morphologically normal hair follicles that produce “rough” or “greasy” hair; thus, KGF’s effects on hair follicle morphogenesis and cycling appear dispensable or replaceable by other growth factors with redundant functions.83

Myelinated sensory nerve fibers run parallel to hair follicles, surrounding them and forming a network.84 Smaller nerve fibers form an outer circular layer, which is concentrated around the bulge of terminal follicles and the bulb of vellus follicles. Several different types of nerve endings, including free nerve endings, lanceolate nerve endings, Merkel cells, and pilo-Ruffini corpuscles are found around hair follicles.85 Each nerve ending detects different forces and stimuli. Free nerve endings transmit pain, lanceolate nerve endings detect acceleration, Merkel cells sense pressure, and pilo-Ruffini structures detect tension. Perifollicular nerves contain neuromediators and neuropeptides, such as substance P or calcitonin gene-related peptide, that influence follicular keratinocytes and alter hair follicle cycling.86–90 Conversely, hair follicle keratinocytes produce neurotrophic factors that influence perifollicular nerves and stimulate their remodeling in hair cycle-dependent manner.90,91 Merkel cells that are considered neuroendocrine cells also produce neurotrophic factors, cytokines, or other regulatory molecules. Because Merkel cells are concentrated in the bulge area, some have postulated that these secreted factors may influence the cycling of the hair follicle.92

The perifollicular sheath envelops the epithelial components of the hair follicle and consists of an inner basement membrane called the hyaline or vitreous (glassy) membrane and an outer connective tissue sheath. The basement membrane of the follicle is continuous with the interfollicular basement membrane. It is most prominent around the outer root sheath at the bulb in anagen hairs. During catagen, the basement membrane thickens and then disintegrates.

Surrounding the basement membrane is a connective tissue sheath comprised primarily of type III collagen. Around the upper follicle, there is a thin connective tissue sheath continuous with the surrounding papillary dermis and arranged longitudinally. Around the lower follicle, the connective tissue sheath is more prominent, with an inner layer of collagen fibers that encircle the follicle surrounded by a layer of longitudinally arranged collagen fibers.66

When transplanted under the skin, this perifollicular connective tissue has the remarkable ability to form a new dermal papilla and induce new hair follicle formation.93 Even when the connective tissue sheath is transplanted to another individual, these follicles survive without evidence of immunologic rejection.

Hair Follicle Cycle

Each individual hair follicle perpetually traverses through three stages: (1) growth (anagen), (2) involution (catagen), and (3) rest (telogen).12 The length of anagen determines the final length of the hair and thus varies according to body site; catagen and telogen duration vary to a lesser extent depending on site. Scalp hair has the longest anagen of 2 years to more than 8 years. Anagen duration in young males at other sites is shorter: legs, 5–7 months; arms, 1.5–3.0 months; eyelashes, 1–6 months; and fingers, 1–3 months. In contrast to most mammals, including mice and newborn humans, in the adult human the hairs of the scalp grow asynchronously. Approximately 90%–93% of scalp follicles are in anagen and the rest primarily in telogen.94 Applying these figures to the 100,000–150,000 hairs on the scalp indicates that approximately 10,000 scalp hairs are in telogen at any given time. However, because we lose only 50–100 hairs per day, this indicates that telogen is a heterogenous state. The follicles that are shedding their hair shaft are thus in “exogen,” which comprises approximately 1% of the telogen hair follicles (see Fig. 86-2 and below). Hair on the scalp grows at a rate of 0.37–0.44 mm/day or approximately 1 cm/month.

Because the lower portion of the follicle cyclically regenerates, hair follicle stem cells were thought to govern this growth. Historically, hair follicle stem cells were assumed to reside exclusively in the “secondary germ” (see Fig. 86-2), which is located at the base of the telogen hair follicle. It was thought that the secondary germ moved downward to the hair bulb during anagen and provided new cells for production of the hair. At the end of anagen, the secondary germ was thought to move upward with the dermal papilla during catagen to come to rest at the base of the telogen follicle. This scenario of stem cell movement during follicle cycling was brought into question when a population of long-lived presumptive stem cells was identified in an area of the follicle surrounding the telogen club hair.95 Subsequently, it was shown that the secondary germ is a transient structure that forms at the end of catagen from cells in the lower bulge.96 The concept that hair follicle stem cells are permanently located in the bulge has now been confirmed using lineage analysis, which showed that the bulge cells give rise to all epithelial layers of the hair follicle.11,97,98 In line with this, ablation of bulge cells results in destruction of the follicle.96 These findings support the notion that loss of hair follicle stem cells in the bulge leads to permanent or cicatricial types of alopecia (see Chapter 88).

Progress has been made in defining subsets of cells within the hair follicle that serve as different stem and progenitor populations. Markers that have been shown through genetic lineage analysis to contribute to the perpetual cycling of the hair follicle, include cytokeratin 15 and Lgr5.96,99 Lgr5, although sometimes touted as an exclusive marker of secondary germ cells, also marks bulge cells. Lgr6, a gene related to Lgr5, is expressed in an area above the bulge in the upper isthmus. The cells marked by Lgr6 migrate to the epidermis during homeostasis and after wounding.100 In addition to these markers, several others demonstrate the heterogeneity of the hair follicle epithelium.101

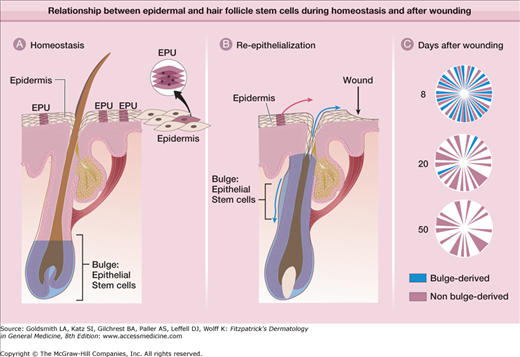

Are bulge cells the “ultimate” stem cells within the skin epithelium? For example, do they generate epidermis and sebaceous glands during homeostasis and after wounding? To answer these questions, lineage analysis and transgenic techniques were again used. As illustrated in Fig. 86-3, bulge cells do not normally move to the epidermis, but after full-thickness excision of the skin, bulge cell progeny migrate into the wound during reepithelialization.11,96 These cells comprise approximately 30% of the cells in the regenerated epidermis. The role of bulge cells in sebaceous gland maintenance is still not clear, but is under investigation.

Figure 86-3

Relationship between epidermal and hair follicle stem cells during homeostasis and after wounding. A. During normal conditions, epidermal renewal is dependent on cell proliferation within epidermal proliferative units (EPUs), which are clonal populations of cells roughly arranged in hexagonally shaped columns that produce a single outer squame. Epithelial stem cells in the hair follicle bulge do not contribute to epidermal renewal. B. After full-thickness wounding, bulge cells contribute cells to the epidermis for immediate wound closure (blue upward arrow). Bulge cells also are required for hair follicle cycling (blue downward arrow) C. Over time, bulge-derived cells diminish, whereas nonbulge-derived cells (from the interfollicular epidermis and infundibulum) appear to predominate in the reepithelialized wound.

The formation of a new lower follicle and hair at anagen onset recapitulates folliculogenesis in the fetus. Anagen can be divided into seven stages: (1) stage I—growth of the dermal papilla and onset of mitotic activity in the germ-like overlying epithelium; (2) stage II—bulb matrix cells envelop the dermal papilla and begin differentiation, evolving bulb begins descent along the fibrous streamer; (3) stage III—bulb matrix cells show differentiation into all follicular components; (4) stage IV—matrix melanocytes reactivate; (5) stage V—hair shaft emerges and dislodges telogen hair; (6) stage VI—new hair shaft emerges from skin surface; and (7) stage VII—stable growth.102

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree