Biology and Pathology of the Oral Cavity: Introduction

|

Introduction

The mouth is the beginning of the aerodigestive tract and an extension of the skin barrier. It plays an important role in mastication, deglutition and digestion, speech, and immunologic defense. The oral mucosa, salivary glands (both major and minor), jawbones, and teeth are frequently the site of primary inflammatory or neoplastic disease. However, the oral cavity may present with manifestations of systemic disease and in some cases, oral findings may precede systemic signs and symptoms by months or years. Lesions in the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity may lead to pain in the upper teeth or may extend inferiorly and present in the maxilla or palate. Metastatic lesions may present as nodules on the gingiva or masses in the jawbones.

Anatomy

![]() The mouth is divided into the mucosa that may be keratinized or nonkeratinized, the appendages (namely, the teeth and salivary glands), the jawbones, and the musculature. It is important to understand the histology of the oral mucosa because some lesions (e.g., minor aphthous ulcers) tend to involve primarily the nonkeratinized tissues: buccal mucosa, labial mucosa (wet surface of the lip), maxillary and mandibular sulcus or vestibule (the “gully” between the jawbones and the buccal or labial mucosa), nonattached gingiva, ventral tongue, floor of mouth, and soft palate. These tissues are movable and abut the underlying fat and muscle. Biopsies at these sites are readily performed with a standard skin punch (eFig. 76-0.1).

The mouth is divided into the mucosa that may be keratinized or nonkeratinized, the appendages (namely, the teeth and salivary glands), the jawbones, and the musculature. It is important to understand the histology of the oral mucosa because some lesions (e.g., minor aphthous ulcers) tend to involve primarily the nonkeratinized tissues: buccal mucosa, labial mucosa (wet surface of the lip), maxillary and mandibular sulcus or vestibule (the “gully” between the jawbones and the buccal or labial mucosa), nonattached gingiva, ventral tongue, floor of mouth, and soft palate. These tissues are movable and abut the underlying fat and muscle. Biopsies at these sites are readily performed with a standard skin punch (eFig. 76-0.1).

![]() Keratinized mucosae comprise the dorsum of the tongue (which is specialized for mastication and taste) with ita filiform, fungiform, and circumvallate papillae; hard palatal mucosa; and attached gingiva (stretching from the gingival margin to the mucogingival junction where the nonattached gingiva begins) (eFig. 76-0.2). The mucosa of the hard palate and attached gingiva both abut the periosteum and skin punch biopsies at these two sites may be difficult to harvest. Unlike most of the gastrointestinal tract, the oral mucosa has no submucosa because it lacks muscularis mucosae. Therefore, the oral mucosa consists of the epithelium and lamina propria (superficial or deep).

Keratinized mucosae comprise the dorsum of the tongue (which is specialized for mastication and taste) with ita filiform, fungiform, and circumvallate papillae; hard palatal mucosa; and attached gingiva (stretching from the gingival margin to the mucogingival junction where the nonattached gingiva begins) (eFig. 76-0.2). The mucosa of the hard palate and attached gingiva both abut the periosteum and skin punch biopsies at these two sites may be difficult to harvest. Unlike most of the gastrointestinal tract, the oral mucosa has no submucosa because it lacks muscularis mucosae. Therefore, the oral mucosa consists of the epithelium and lamina propria (superficial or deep).

Evaluation of the Patient

As with evaluation of the skin, obtaining a comprehensive medical and medication history and careful inquiry into current symptoms are essential. The extraoral examination should begin with an examination of the skin of the face and in particular the perioral region, palpation of the submandibular and submental lymph nodes, and palpation of the temporomandibular joints for clicking or pain on opening. Clicking with no pain occurs in 20%–30% of the population and is of no clinical significance but should be noted. Clicking with pain and/or limitation of opening may indicate temporomandibular joint myofascial pain syndrome and requires referral to a dental specialist for management.

The mucosal surfaces as outlined above, taking note of where the lesions are located, and in particular, whether they are on the keratinized or nonkeratinized sites.

The presence or absence of saliva in the floor of mouth and whether the saliva is of the usual watery consistency or whether it is ropey.

The dentition and whether there are grossly carious teeth.

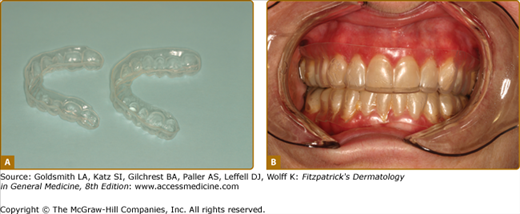

The use of a removable prosthesis (upper and/or lower dentures—complete or partial); this is particularly important for some mucosal diseases caused by denture trauma and for the diagnosis and treatment of candidiasis since the denture acts as a fomite.

Normal Anatomic Structures

There are several structures in the oral mucosa that are considered variations of normal. These include:

Fordyce granules: These are sebaceous glands that present as painless yellow papules, 1–2 mm in diameter located in a bilateral symmetric fashion on the posterior buccal mucosa, and lips (usually vermilion) (Fig. 76-1). Sebaceous hyperplasia of these glands may form discrete larger yellow papules several millimeters in size.

Linea alba: This is a linear keratosis located on the buccal mucosa bilaterally where the upper and lower teeth meet. It is a form of frictional keratosis and exaggeration of this is seen in patients who habitually chew the buccal mucosa, a condition known as morsicatio mucosae oris (MMO) (see below).

Palatal and mandibular tori: These are benign, usually symmetric exostoses that are present in the midline of the hard palate or bilaterally on the lingual aspect of the mandible (Fig. 76-2). They may be large and multilobated, but patients are usually unaware of their presence.

Prescribing Topical Medications

Topical steroids are the mainstay of treatment for many inflammatory and autoimmune mucosal diseases.1 The only topical steroid that is FDA-approved for intraoral use is Kenalog-in-Orabase dental paste (0.1% triamcinolone; Apethecon, Princeton, NJ). This is a Class IV steroid and is weakly efficacious as an anti-inflammatory agent in the oral cavity, although the Orabase (methylcellulose) is useful and soothing as a covering agent in some conditions. In general, most oral medicine specialists use fluocinolone, fluocinonide, clobetasol, and topical tacrolimus for the management of mucosal disease. Principles applying to use of these medications in the oral cavity regardless of specific diagnosis are found in Table 76-1 and eBox 76-0.1.

Medication | How to Prescribe |

|---|---|

Topical immunosuppressive agents | |

Triamcinolone 0.1% dental paste | 5-mg tube; apply to affected site tid or qid (this forms a barrier) |

Fluocinolone 0.05% gel Clobetasol 0.05% gel Betamethasone 0.05% gel | 15-60 g tube dry area, apply to affected site tid or qid; no food or drink for 30 minutes after OR Place gel in stent and wear for 30 minutes, bid or tid |

Dexamethasone elixir 0.5 mg/5 mL Prednisolone syrup (15 mg/5 mL) Tacrolimus solution (5 mg/mL) Cyclosporine (100 mg/mL) | Dispense 300–500 mL; swish 5 mL. (dexamethasone, tacrolimus, or cyclosporine) or 5–10 mL. (prednisolone) for 3 minutes (timed) and spit out tid or qid; no food or drink for 30 minutes after |

Nasal sprays used orally (such as fluticasone and budesonide) | 1–2 puffs 2–3 times a day |

Intralesional steroid injection with triamcinolone | 1–5 mg triamcinolone per cm2 of ulceration |

Antifungal therapy | |

Nystatin 1:100,000 units/mLa | Dispense 300–500 mL; swish and spit out (or swallow) 5 mL tid or qid |

Clotrimazole 10 mg trochesa | Suck on one troche tid or qid |

Fluconazole 100 mg | Take one tablet in the morning qd × 3–10 days (depending on the severity of the infection) |

Mycostatin/triamcinolone cream | Apply to corners of mouth tid or qid for angular cheilitis Paint onto denture base tid and wear denture |

Denture treatment in patients with candidiasis Denture soaks such as: Nystatin 1:100,000 units/mL Chlorhexidine digluconate 0.12% 3% sodium hypochlorite diluted in water (1:10) 2% sodium benzoate | Soak denture in solution overnight. |

Topical pain medications | |

Viscous lidocaine 2% | Swish and spit out tid or qid for pain |

Benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% | |

Dyclonine hydrochloride 1% | |

Systemic immunosuppressive therapy | Topical therapy should be started concomitant with systemic therapy. |

Prednisone | 0.5–1.0 mg/kg to begin for 7–10 days with a rapid taper over 2–3 weeks |

Pentoxifylline | 400 mg three times a day or 800 mg twice a day |

Hydroxychloroquine | 200–400 mg daily |

Dapsone | 25 mg to begin, increasing to 75–100 mg/day |

Mycophenolate mofetil | 1000–3000 mg daily |

Colchicine | 0.6 mg once or twice a day |

Azathioprine | 50–100 mg daily |

Thalidomide | 50–100 mg tid to begin; begin taper to maintenance dose (which may be weekly) or discontinue completely |

|

Viscous lidocaine (2%) may be used alone or combined with diphenhydramine, Kaopectate (Pfizer, NY), or Maalox (Novartis, NJ) in equal volumes as a swish and spit out preparation for pain control. This is particularly useful for diffuse painful lesions, acute or chronic.

Localized ulcers may be treated with over-the-counter benzocaine preparations, or covering agents such as methylcellulose (Orabase; Colgate-Palmolive, NY).

As with any disease condition, provision of up-to-date information on the disease allays many fears and misconceptions, empowers patients, and helps patients to better understand their condition. Information on the nature, management, and prognosis of common mucosal conditions are available on the Web sites of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (www.aaomp.org) and the American Academy of Oral Medicine (www.aaom.com). These can be modified to suit your practice needs.

Oral Manifestations of Systemic Disease and Syndromes

Systemic diseases often have distinctive presentations in the oral cavity and many skin conditions also have concomitant oral findings. eTable 76-1.1 provides a list of some of the more common systemic diseases and syndromes that present with oral findings. Some are discussed in greater detail below.

DISORDER | ORAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|

|

|

Disease Classification

The disease entities to be described are those normally treated by the dermatologist and are divided primarily into how the lesions present clinically (e.g., ulcers, nodules, or red and white lesions). However, there is also a section based on lesions that are site-specific. Pathogenetic mechanisms for diseases such as the autoimmune bullous disorders will not be discussed in any detail since they are presented elsewhere in this book.

The oral ulcer appears as a yellow–white papule or plaque of fibrin (often referred to as a “pseudomembrane”), usually with a surrounding red rim. It does not appear crusty because of the wet environment. Such lesions are always painful unless the ulcer represents a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which is often painless. Several conditions fall into this category and only the most common will be discussed here (eTable 76-1.2).

Reactive

|

Infectious

|

Immune-mediated

|

Neoplastic

|

Idiopathic aphthous ulcers |

Aphtheiform ulcers associated with:

|

Recurrent aphthous ulcer (RAU) is a T-cell-mediated disorder and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α plays an important role in its occurrence.2 There is usually a family history of aphthous ulcers and there is a significant association with a number of HLA-haplotypes.3 Stress, systemic illness, and local trauma predisposes to their occurrence in susceptible individuals.

Aphtheiform ulcers are aphthous-like in their appearance and history but they may occur sometimes on the dorsum of the tongue if they are a result of hematinic deficiency or inflammatory bowel disease. RAU are seen in all patients with Behçet disease and may precede other findings by years. Behçet disease, a vasculitic disorder, has a predilection for Turkish and Japanese populations and is associated with an increase in HLA-B51.4 In periodic fever-adenopathy, pharyngitis, aphthae (PFAPA) syndrome, ulcers are often so severe that children miss days at school.5,6 Patients with other systemic or skin conditions and aphthous ulcers form part of the “complex aphthosis” syndrome and include those with MAGIC (mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage) syndrome (eTable 76-1.2). Approximately 3% of patients with RAU have gluten-sensitive enteropathy7 and some show sensitivity to foods and sodium lauryl sulfate.

Idiopathic RAU occurs in 15%–20% of the population beginning in the second decade of life and the disease generally becomes less severe over the age of 50. Patients often report the sensation of a small nodule beneath the epithelium before the ulcer appears. The painful yellow–white ulcers are surrounded by an erythematous halo.

There are four clinical forms of RAU and these are always painful:

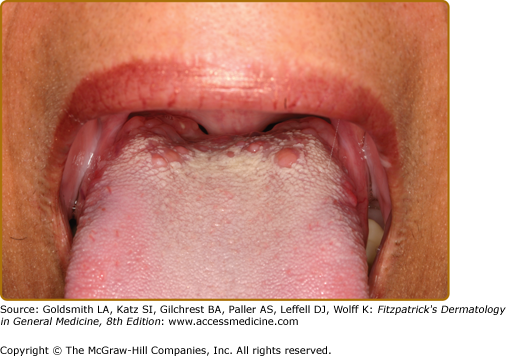

Minor ulcers (<1 cm, 1–10 at each episode lasting 1–2 weeks) (Fig. 76-3A); this is by far the most common form.

Major ulcers (>1 cm lasting several weeks and healing with scarring) (Fig. 76-3B).

Herpetiform ulcers (<1 cm, usually 0.1–0.5 cm each, >10 clustered ulcers at each episode, lasting 1–2 weeks (Fig. 76-3C).

Severe aphthous ulcers where patients have minor ulcers but with continuous ulcerations with minimum or no ulcer-free days for months.

Idiopathic RAU are almost always confined to the nonkeratinized mucosa. They may occur on the nonattached gingiva, but generally do not cross the mucogingival junction onto the attached gingiva, except in some cases of RAU major.

Traumatic lesions must be considered because the oral cavity is subject daily to mechanical trauma (such as mastication) (eTable 76-1.2). However, traumatic ulcers are not the same as RAU, although patients with RAU readily develop ulcers at sites of trauma. A history of trauma and the nonepisodic nature of the condition help to differentiate between traumatic ulcers and those of RAU. Chemotherapy-associated ulcers are not generally considered aphthous ulcers but rather chemotherapy- and neutropenia-associated (similar to cyclic neutropenia); they also tend to occur on the nonkeratinized mucosa. Herpetic ulcers in healthy patients occur intraorally on the keratinized mucosa of the gingival margin and the palate. However, in immunocompromised patients, they may resemble RAU, especially RAU major in patients with HIV disease. Culture and biopsy (Box 76-1) are indicated in such patients. Lesions of chronic recurrent oral erythema multiforme must also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Oral manifestations of Crohn disease and other gastrointestinal conditions are discussed below.

A biopsy of any mucosal condition is readily performed with a skin punch (3–5 mm in diameter). Here are a few helpful suggestions:

|

The biopsy is nonspecific and shows only a fibrin membrane with acute and chronic inflammation and granulation tissue, but may exclude an infectious etiology.

Any positive findings should be followed up. For example, it may be useful to keep a food diary and to change toothpaste to one that does not contain sodium lauryl sulfate. In most cases, the work-up is negative.

The treatment for minor RAU is topical steroids (Table 76-1) or intralesional steroid injection if the ulcers are large and persistent, especially those of aphthous major or in patients with HIV disease. Topical agents that may be useful include cyanoacrylate (Soothe-N-Seal; Colgate Palmolive, NY) and anti-inflammatory agents such as amlexanox 5% paste (Aphthasol, Uluru, Texas), 2 mg amlexanox mucoadhesive disc (Oradisc, Uluru, Texas), or tetracycline oral rinse. Lesions may also be cauterized with 28%–50% sulfuric acid and sulfonated phenolics (Debacterol, Epien Medical Inc.) or with silver nitrate (shaving sticks). Topical anesthetics in paste form are available over-the-counter, in particular benzocaine of varying strengths. Systemic therapy with prednisone for a few weeks and maintenance with pentoxifylline may reduce the number, duration and size of ulcers, and reduce the number of episodes. In appropriate patients, thalidomide therapy is extremely effective, although patients often develop irreversible neuropathy with long-term use. Other agents that are variably efficacious include colchicine and azathioprine.

The most common bowel diseases associated with oral ulcers are Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, malabsorption syndromes leading to hematinic deficiency, and celiac disease.8

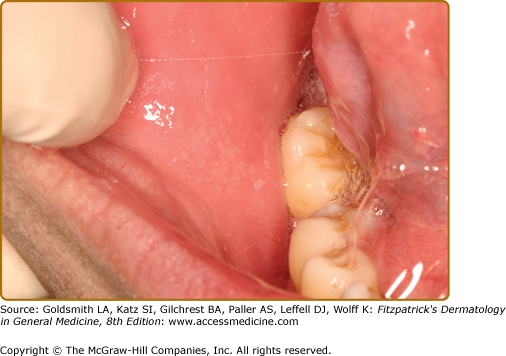

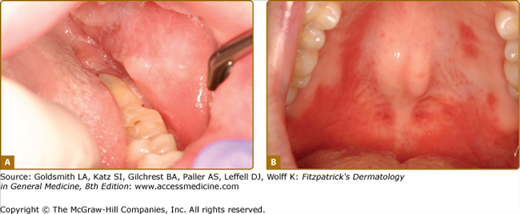

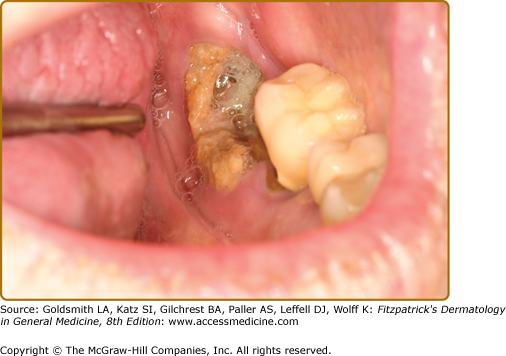

Oral lesions are seen in up to 20% of patients with Crohn disease if nonspecific mucogingivitis is excluded.9 Ulcers of Crohn disease typically present as linear lesions along the maxillary and mandibular vestibule/sulcus (Fig. 76-4A). In addition, patients often also present with papulous folds of tissues, swelling of the lips (indistinguishable from cheilitis granulomatosa), and cobblestoning of the mucosa.10 Other manifestations of Crohn disease include severe and diffuse erythema and inflammation of the mucosa, sometimes associated with Staphylococcus aureus infection (Fig. 76-4B).11 A reliable finding is a dusky-red firm area of the perivermilion skin that has a slight pitted, “orange peel” appearance.

Pyostomatitis vegetans (oral analog of pyoderma gangrenosum) associated with inflammatory bowel disease presents as “snail-track” ulcers of the oral mucosa.12 Dental enamel defects (enamel hypoplasia) are associated with celiac disease in children.13

Oral ulcers ultimately associated with inflammatory bowel disease may predate gastrointestinal lesions by years in up to 60% of patients,10 so that absence of gastrointestinal symptoms does not exclude this etiology. Elevated tissue transglutaminase and the presence of endomysial antibodies support the diagnosis of celiac disease.

A biopsy of oral lesions of Crohn disease shows granulomatous inflammation or while pyostomatitis vegetans shows acantholysis.

In the absence of gastrointestinal findings, treatment is with topical steroid therapy and in severe cases, prednisone for rapid control of lesions with maintenance on topical steroids or other anti-inflammatory agents similar to the protocol for management of idiopathic aphthous ulcers.14 If gastrointestinal disease is active, this should be brought under control first and oral ulcers may then resolve.

Oral manifestations generally wax and wane with the severity of systemic disease.

Damage from chemotherapy agents is mediated via production of cytokines, cytokine modulators, and stress responders, leading to apoptosis of dividing epithelial cells.15 Ulcers are potential portals for bacteremia and septicemia, particularly because patients are also often neutropenic. Depending on the regimen, 25%–30% of patients develop this complication. Agents often associated with such lesions include cytarabine and cisplatin, especially when combined with radiation.

These ulcers are generally located on the nonkeratinized sites and in particular the buccal mucosa and ventral tongue. They begin within 3–5 days of the start of chemotherapy and generally resolve when absolute neutrophil counts recover, usually a course of 7–10 days. Lesions are extremely painful and may measure several centimeters in size.16

Recrudescent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection is common in immunocompromised patients such as patients with cancer and, unlike in healthy hosts, often occurs on nonkeratinized sites. Hence, patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, if seropositive for HSV antibodies, are prophylactically placed on antiviral agents during their hospital course. However, a positive culture may represent shedding of HSV in the oral fluids and saliva rather than true recrudescence within the ulcers.

Deep fungal infections and cytomegalovirus infection may all present with large ulcers on the mucosa, but these generally do not heal with recovery of neutrophil counts.

Radiation to the head and neck leads to severe erythema, inflammation, and ulceration (radiation mucositis).17,18

In patients who have received allogenic hematopoietic transplants, persistence of oral ulcers after engraftment may herald the development of acute graft-versus-host disease. In such situations, involvement of the keratinized tissues of the tongue dorsum and hard palate is not uncommon.

Ulcers are self-limiting and therapy is directed toward pain control and prevention of septicemia from bacterial ingress into the oral wounds.19 Patients are often treated with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor to reduce the period of neutropenia and this has reduced the frequency of such ulcers.

Topical analgesia such as viscous lidocaine and systemic analgesia (especially narcotics) is the mainstay of pain control. Although chlorhexidine is often used for decontamination, its high alcohol content makes patient compliance poor. Other oral decontamination rinses contain nystatin and antibiotics.

Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma (Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma with Stromal Eosinophilia, Eosinophilic Ulcer of the Tongue)

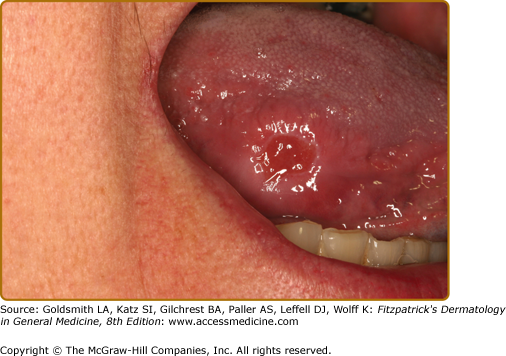

![]() This condition is likely caused by trauma (possibly repeated) that leads to a penetrating injury and inflammation involving the underlying skeletal muscle. Although only 50% of patients give a history of trauma, this condition has been experimentally induced in dogs using physical trauma.

This condition is likely caused by trauma (possibly repeated) that leads to a penetrating injury and inflammation involving the underlying skeletal muscle. Although only 50% of patients give a history of trauma, this condition has been experimentally induced in dogs using physical trauma.

![]() Traumatic ulcerative granuloma is a not uncommon condition. In children, it usually occurs in the first year of life with eruption of the mandibular deciduous incisors that traumatize the ventral surface of the tongue (Riga–Fede disease). In adults, the most common location is the lateral or ventral tongue.20,21 As a disease strongly associated with muscle injury, it may arise anywhere in the oral cavity with underlying muscle. Lesions may raise suspicion of oral cancer because of presentation as a nonhealing, often painless ulcer and sometimes fungating mass (eFig. 76-4.1). There may be bilateral synchronous lesions and they may recur. Some traumatic ulcerative granulomas develop from other ulcerative conditions [e.g., recurrent aphthous major, HIV ulcers, and ulcerative lichen planus (LP)] that are repeatedly traumatized.

Traumatic ulcerative granuloma is a not uncommon condition. In children, it usually occurs in the first year of life with eruption of the mandibular deciduous incisors that traumatize the ventral surface of the tongue (Riga–Fede disease). In adults, the most common location is the lateral or ventral tongue.20,21 As a disease strongly associated with muscle injury, it may arise anywhere in the oral cavity with underlying muscle. Lesions may raise suspicion of oral cancer because of presentation as a nonhealing, often painless ulcer and sometimes fungating mass (eFig. 76-4.1). There may be bilateral synchronous lesions and they may recur. Some traumatic ulcerative granulomas develop from other ulcerative conditions [e.g., recurrent aphthous major, HIV ulcers, and ulcerative lichen planus (LP)] that are repeatedly traumatized.

![]() The most important differential diagnosis is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Any neoplasm arising in the deep tissues of the lateral border of the tongue (such as from salivary gland of soft tissues) may become traumatized and ulcerated.

The most important differential diagnosis is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Any neoplasm arising in the deep tissues of the lateral border of the tongue (such as from salivary gland of soft tissues) may become traumatized and ulcerated.

![]() Biopsy is usually indicated and shows myositis associated with a proliferation of histiocyte-like mononuclear cells and many eosinophils. Although some cases seem to represent CD30+ lymphoma, even lesions monoclonal for CD30+ cells heal uneventfully.22–24

Biopsy is usually indicated and shows myositis associated with a proliferation of histiocyte-like mononuclear cells and many eosinophils. Although some cases seem to represent CD30+ lymphoma, even lesions monoclonal for CD30+ cells heal uneventfully.22–24

![]() TUG is best treated with excision or intralesional steroid injections. Some lesions will resolve after the biopsy. Lesions may recur or new lesions may appear elsewhere.25

TUG is best treated with excision or intralesional steroid injections. Some lesions will resolve after the biopsy. Lesions may recur or new lesions may appear elsewhere.25

![]() Acute primary viral infections in the oral cavity that result in ulcers include those caused by coxsackievirus, enterovirus, and Herpesviridae.26 All are associated with fever, malaise, sore throat, and usually lymphadenopathy. Coxsackievirus infection (including infection by enterovirus-70) often occurs in seasonal epidemics in schoolchildren and takes several oral forms. Herpangina tends to present with ulcers in the posterior oral cavity and pharynx, while ulcers of hand-foot-mouth disease may be found anywhere in the oral cavity, usually but not always with attendant skin lesions. Lymphonodular pharyngitis is characterized by the occurrence of a sore throat and numerous pinkish-yellow lymphoid nodules in the oropharynx.

Acute primary viral infections in the oral cavity that result in ulcers include those caused by coxsackievirus, enterovirus, and Herpesviridae.26 All are associated with fever, malaise, sore throat, and usually lymphadenopathy. Coxsackievirus infection (including infection by enterovirus-70) often occurs in seasonal epidemics in schoolchildren and takes several oral forms. Herpangina tends to present with ulcers in the posterior oral cavity and pharynx, while ulcers of hand-foot-mouth disease may be found anywhere in the oral cavity, usually but not always with attendant skin lesions. Lymphonodular pharyngitis is characterized by the occurrence of a sore throat and numerous pinkish-yellow lymphoid nodules in the oropharynx.

![]() Herpes virus infections take various forms depending on the virus involved (Table 76-2).26 Only 20%–40% of patients infected with HSV develop recrudescent lesions. However, asymptomatic shedding occurs with high frequency and is the most common cause of transmission. The ulcers of primary HSV and recrudescent oral HSV (including herpes labialis) are clustered and coalescent (Figs. 76-5A–76-5C), while recrudescent HSV in immunocompromised hosts may present as a single aphtheiform ulcer.27 Herpes labialis has distinct stages starting with a prodrome of tingling, then formation of a papule, vesicle, crust, and resolution. During the healing stage of HSV infection on the tongue dorsum, lesions are often depressed granulating ulcers with sharply demarcated borders, a condition referred to as “herpetic geographic glossitis.”

Herpes virus infections take various forms depending on the virus involved (Table 76-2).26 Only 20%–40% of patients infected with HSV develop recrudescent lesions. However, asymptomatic shedding occurs with high frequency and is the most common cause of transmission. The ulcers of primary HSV and recrudescent oral HSV (including herpes labialis) are clustered and coalescent (Figs. 76-5A–76-5C), while recrudescent HSV in immunocompromised hosts may present as a single aphtheiform ulcer.27 Herpes labialis has distinct stages starting with a prodrome of tingling, then formation of a papule, vesicle, crust, and resolution. During the healing stage of HSV infection on the tongue dorsum, lesions are often depressed granulating ulcers with sharply demarcated borders, a condition referred to as “herpetic geographic glossitis.”

HHV1 (herpes simplex-1) | (a) Primary gingivostomatitis, usually in first to third decades of life (b) Herpes labialis and recrudescent herpetic ulcers on the attached mucosa in healthy patients; in adults (c) Ulcers on any oral mucosal site in immunocompromised patients |

HHV2 (herpes simplex-2) | May present with oral ulcers similar to HSV-1; young adults |

HHV3 (varicella zoster) | Primary infection may or may not have oral ulcers; recrudescent with unilateral ulcers along distribution of VII or VIII; adults and immunocompromised patients |

HHV4 (Epstein–Barr) | Oral ulcers in infectious mononucleosis in young adults; nasopharyngeal carcinoma in older adults, hairy leukoplakia in patients with HIV/AIDS |

HHV5 (cytomegalovirus) | Oral ulcers; may be seen associated with HSV ulcers; usually in immunocompromised patients |

HHV6 | Unlikely to have oral manifestations |

HHV7 | Unlikely to have oral manifestations |

HHV8 | Kaposi sarcoma; usually seen in patients with HIV/AIDS |

HHV 9 (simian) | Unlikely to be seen in humans |

![]() Oral recrudescent varicella-zoster virus usually presents as clustered ulcers affecting one side of the mouth but atypical findings may be noted in patients who are immunocompromised.

Oral recrudescent varicella-zoster virus usually presents as clustered ulcers affecting one side of the mouth but atypical findings may be noted in patients who are immunocompromised.

![]() Erythema multiforme and vesiculobullous disorders may result in multiple ulcers, but these are not usually small and coalescent. Vesiculobullous disorders are chronic, relapsing, and recurrent (see below).

Erythema multiforme and vesiculobullous disorders may result in multiple ulcers, but these are not usually small and coalescent. Vesiculobullous disorders are chronic, relapsing, and recurrent (see below).

![]() The presence of HSV in cultures and by direct fluorescent antibody testing must always be correlated with clinical findings because HSV sheds in the saliva and oral secretions. The identification of multinucleated giant epithelial in a cytologic smear or in a tissue biopsy at the edge of the ulcer is typical for a herpes infection and immunohistochemical or in situ hybridization studies are then confirmatory.

The presence of HSV in cultures and by direct fluorescent antibody testing must always be correlated with clinical findings because HSV sheds in the saliva and oral secretions. The identification of multinucleated giant epithelial in a cytologic smear or in a tissue biopsy at the edge of the ulcer is typical for a herpes infection and immunohistochemical or in situ hybridization studies are then confirmatory.

![]() Patients need supportive care for fever and pain (topical and systemic analgesics), as well as hydration.

Patients need supportive care for fever and pain (topical and systemic analgesics), as well as hydration.

![]() Primary oral HSV and recrudescent HSV in immunocompromised hosts should be treated with acyclovir or valacyclovir within the first 1–3 days to reduce viral shedding and shorten disease course. However, after that period of time, it is unclear if antiviral drugs are effective. Once formed, ulcers take several days to resolve regardless of antiviral therapy. Recrudescent HSV may be treated with episodic therapy or prophylactic therapy. Herpes labialis may often be prevented or aborted by sunscreen use. Recrudescent lesions, at first prodrome of tingling, may be treated with topical acyclovir (5% cream), penciclovir (1% cream), docosanol (10% cream), valacyclovir (2 g twice daily for 1 day), or even a single dose of famciclovir (1,500 mg).28

Primary oral HSV and recrudescent HSV in immunocompromised hosts should be treated with acyclovir or valacyclovir within the first 1–3 days to reduce viral shedding and shorten disease course. However, after that period of time, it is unclear if antiviral drugs are effective. Once formed, ulcers take several days to resolve regardless of antiviral therapy. Recrudescent HSV may be treated with episodic therapy or prophylactic therapy. Herpes labialis may often be prevented or aborted by sunscreen use. Recrudescent lesions, at first prodrome of tingling, may be treated with topical acyclovir (5% cream), penciclovir (1% cream), docosanol (10% cream), valacyclovir (2 g twice daily for 1 day), or even a single dose of famciclovir (1,500 mg).28

Zygomycosis is a broad term used to describe fungal infections caused by organisms in the phylum Zygomycota. These include infections caused by organisms in the family Mucorales with organisms in the genera Mucor and Rhizopus. These are unusual infections, seen usually in patients who have diabetes mellitus (usually ketoacidotic) or are immunocompromised, and are often life threatening. Organisms are inhaled and spread into the adjacent sinuses, eroding through the bone, sometimes presenting on the palate as a necrotic ulcer, a condition also referred to as rhinocerebral zygomycosis.29 Aspergillus infections are seen in neutropenic patients, especially those with leukemia and tend to present as necrotic soft tissue and bony lesions of the gingiva, while histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis are seen in areas where such infections are endemic such as in South America and in patients with HIV/AIDS.30–33

Unlike candidiasis, deep fungal infections usually present as necrotic ulcers because they are angioinvasive organisms that cause vascular thrombosis and ischemia. The most common location for rhinocerebral zygomycosis is the palate, although fungal infections in immunocompromised patients may occur at any site in the mouth.

Deep fungal infections involving the palate or maxilla are an important differential diagnosis for the clinical entity “midline destructive disease.” Other conditions that fall into this category include NKT-cell lymphoma, other infections such as tertiary syphilis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener disease), cocaine use, and epithelial malignancy of surface or salivary gland origin.34 A biopsy readily distinguishes among these entities.

Because these are deep infections, a swab culture may not capture any organisms. A biopsy shows the presence of hyphae. It is useful to submit part of the harvested tissue in saline for speciation in a microbiology laboratory.

A biopsy shows necrosis and inflammation. The morphology of hyphae seen on special stains, together with culture results, confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment is with systemic antifungal agents such as liposomal amphotericin and triazole antifungal agents such as fluconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole, often with surgical debridement.35 Mortality is often high in poorly controlled infection. Reducing environmental exposures is a particularly important prophylactic measure for immunocompromised patients.

![]() Ulcers from vascular compromise that occur in the oral cavity tend to occur acutely and two are well recognized: (1) ulcers after injection of local anesthesia, and (2) ulcers from necrotizing sialometaplasia.

Ulcers from vascular compromise that occur in the oral cavity tend to occur acutely and two are well recognized: (1) ulcers after injection of local anesthesia, and (2) ulcers from necrotizing sialometaplasia.

![]() Dental anesthetics generally contain 1:50,000 or 1:100,000 epinephrine. The most common location for ulcers caused by dental anesthetics is the hard palatal mucosa after a greater palatine block.21 Within 1–2 days of the procedure, an ulcer, usually 1–2 cm, develops around the area of the introduction of the anesthesia (eFig. 76-5.1). Over a period of a few days, the ulcers resolve.

Dental anesthetics generally contain 1:50,000 or 1:100,000 epinephrine. The most common location for ulcers caused by dental anesthetics is the hard palatal mucosa after a greater palatine block.21 Within 1–2 days of the procedure, an ulcer, usually 1–2 cm, develops around the area of the introduction of the anesthesia (eFig. 76-5.1). Over a period of a few days, the ulcers resolve.

![]() Vascular compromise may lead to necrotic ulcers in necrotizing sialometaplasia, an infarction of salivary gland tissue that presents first with a slight swelling followed by break down of the mucosa leading to an ulcer with sharply demarcated margins, and then resolution over a period of weeks.36,37 Infrequently, cases may be bilateral,38 or associated with bulimia.39

Vascular compromise may lead to necrotic ulcers in necrotizing sialometaplasia, an infarction of salivary gland tissue that presents first with a slight swelling followed by break down of the mucosa leading to an ulcer with sharply demarcated margins, and then resolution over a period of weeks.36,37 Infrequently, cases may be bilateral,38 or associated with bulimia.39

![]() The fairly superficial nature of these ulcers, their sharp border, relatively small size, and short duration differentiates this from long-standing ulcers of systemic vasculitides and lesions of “midline destructive disease” (see below).

The fairly superficial nature of these ulcers, their sharp border, relatively small size, and short duration differentiates this from long-standing ulcers of systemic vasculitides and lesions of “midline destructive disease” (see below).

![]() In general, lesions caused by dental anesthesia are rarely biopsied. Lesions of necrotizing sialometaplasia show infarction of salivary glands and squamous metaplasia of ducts.

In general, lesions caused by dental anesthesia are rarely biopsied. Lesions of necrotizing sialometaplasia show infarction of salivary glands and squamous metaplasia of ducts.

![]() Lesions of acute vascular compromise are short-lived and generally resolve spontaneously. However, larger and more persistent lesions may be amenable to topical or intralesional steroid therapy.

Lesions of acute vascular compromise are short-lived and generally resolve spontaneously. However, larger and more persistent lesions may be amenable to topical or intralesional steroid therapy.

![]() Signs of systemic vasculitides in the oral cavity rarely occur in the absence of significant skin findings and patients usually present with an established diagnosis for management of mucosal lesions. The exception is granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s).

Signs of systemic vasculitides in the oral cavity rarely occur in the absence of significant skin findings and patients usually present with an established diagnosis for management of mucosal lesions. The exception is granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s).

![]() Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) presents in its full expression with involvement of the upper respiratory tract and oral mucosa with necrotizing granulomas, and involvement of small-to-medium-sized vessel with necrotizing vasculitis.40 Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common. It falls under the larger category of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides that also include microscopic polyangiitis, Churg–Strauss syndrome, and renal-limited vasculitis,41 granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener disease) is associated with HLA-DPB1. Autoantibodies are directed against granules of neutrophils and lysosomes of monocytes. There is a strong association of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and increased risk for relapsing disease.41 There is a limited form of the disease that affects only the upper airways and oral cavity.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) presents in its full expression with involvement of the upper respiratory tract and oral mucosa with necrotizing granulomas, and involvement of small-to-medium-sized vessel with necrotizing vasculitis.40 Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common. It falls under the larger category of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides that also include microscopic polyangiitis, Churg–Strauss syndrome, and renal-limited vasculitis,41 granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener disease) is associated with HLA-DPB1. Autoantibodies are directed against granules of neutrophils and lysosomes of monocytes. There is a strong association of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and increased risk for relapsing disease.41 There is a limited form of the disease that affects only the upper airways and oral cavity.

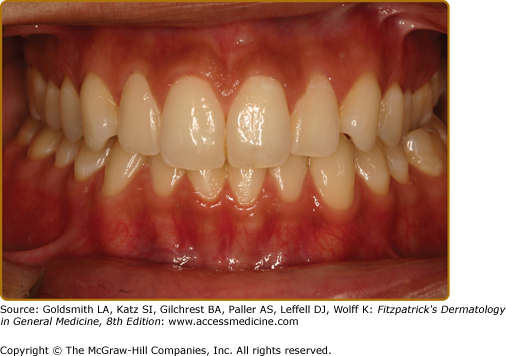

![]() Oral findings are the first presentation in approximately 6%–13% of patients.42,43 Patients are usually adults and present with painful, necrotic ulcers of the oral mucosa, in particular the hard palate. This disease is one of the differential diagnoses for “midline destructive disease” (see below). A classic presentation is that of “strawberry gingivitis” where the gingiva has a pebbly, erythematous, and hyperplastic appearance with petechia.

Oral findings are the first presentation in approximately 6%–13% of patients.42,43 Patients are usually adults and present with painful, necrotic ulcers of the oral mucosa, in particular the hard palate. This disease is one of the differential diagnoses for “midline destructive disease” (see below). A classic presentation is that of “strawberry gingivitis” where the gingiva has a pebbly, erythematous, and hyperplastic appearance with petechia.

![]() “Midline destructive disease” is a term used to describe progressive, necrotic, and ulcerative lesions of the palate that may represent a variety of conditions such as lymphoma (especially NKT-cell lymphoma), deep fungal infection, tertiary syphilis, ulcers from cocaine use, malignancies of the salivary glands, and SCC either of oral origin, or from the sinuses.34 Location of these fairly large ulcers on the palate generally rules out aphthous ulcers but recrudescent herpetic stomatitis must be considered.

“Midline destructive disease” is a term used to describe progressive, necrotic, and ulcerative lesions of the palate that may represent a variety of conditions such as lymphoma (especially NKT-cell lymphoma), deep fungal infection, tertiary syphilis, ulcers from cocaine use, malignancies of the salivary glands, and SCC either of oral origin, or from the sinuses.34 Location of these fairly large ulcers on the palate generally rules out aphthous ulcers but recrudescent herpetic stomatitis must be considered.

![]() Swollen, diffuse, erythematous gingival overgrowth raises several other differential diagnoses (eTable 76-2.1).

Swollen, diffuse, erythematous gingival overgrowth raises several other differential diagnoses (eTable 76-2.1).

Diagnosis | Clinical Appearance and Treatment |

|---|---|

Developmental Fibromatosis gingivae | Dense, pink, fibrotic-appearing tissue in a symmetric pattern, usually affecting the maxilla. Excision is the treatment of choice. |

Reactive Poor oral hygiene Hormonal (puberty or pregnancy Drug-induced (dilantin, cyclosporine, calcium channel blocker) | Color varies from pink to erythematous with areas of ulceration depending on the degree of inflammation present which in turn, is associated with the degree of plaque accumulation. Excision with professional scaling, and good oral hygiene measures, including the use of chlorhexidine mouth rinse, and/or low-dose doxycycline (10 mg/day—not in pregnant patients). |

Metabolic Ligneous gingivitis/periodontitis | Nodular yellowish lesions composed mainly of fibrin on the gingiva Excision with professional scaling, and good oral hygiene measures, including the use of warfarin, chlorhexidine mouth rinse, and/or low-dose doxycycline. Genetic testing may be warranted. |

Immune-mediated Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s disease) Orofacial granulomatosis | Usually erythematous with petechiae; in classic presentation “strawberry gingivitis.” |

Neoplastic Leukemia (esp. acute monocytic) | Usually pink only in very lesions; rapidly become erythematous, boggy, and often ulcerated. Chemotherapy resolves lesions. |

![]() Indirect immunofluorescence testing reveals the presence of ANCA in a cytoplasmic (cANCA) pattern usually ELISA positive for antibodies against proteinase-3, while the perinuclear (pANCA) pattern is associated with ELISA positivity for antibodies against myeloperoxidase. The c-ANCA pattern is particularly important in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener disease).44

Indirect immunofluorescence testing reveals the presence of ANCA in a cytoplasmic (cANCA) pattern usually ELISA positive for antibodies against proteinase-3, while the perinuclear (pANCA) pattern is associated with ELISA positivity for antibodies against myeloperoxidase. The c-ANCA pattern is particularly important in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener disease).44

![]() A biopsy reveals geographic necrosis, necrotizing granulomas, and vasculitis.

A biopsy reveals geographic necrosis, necrotizing granulomas, and vasculitis.

![]() Patients are treated with high-dose prednisone and cytotoxic therapy such as cyclophosphamide usually for many months.45 Treatment and/or maintenance with methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil mitigates toxicity of prolonged cyclophosphamide use. Surgical reconstruction may be necessary if there has been extensive tissue destruction. The use of rituximab for refractory disease has recently been found to be useful.45,46

Patients are treated with high-dose prednisone and cytotoxic therapy such as cyclophosphamide usually for many months.45 Treatment and/or maintenance with methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil mitigates toxicity of prolonged cyclophosphamide use. Surgical reconstruction may be necessary if there has been extensive tissue destruction. The use of rituximab for refractory disease has recently been found to be useful.45,46

![]() There is no fibrin clot overlying the lesion; rather, necrotic bone is exposed. The etiologies include vascular compromise (such as in osteoradionecrosis and postherpes zoster infections), physical and chemical trauma (such as chronic cocaine use), and suppression of bone turnover (bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws).47–49

There is no fibrin clot overlying the lesion; rather, necrotic bone is exposed. The etiologies include vascular compromise (such as in osteoradionecrosis and postherpes zoster infections), physical and chemical trauma (such as chronic cocaine use), and suppression of bone turnover (bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws).47–49

![]() Depending on the etiology, there is some variation in the clinical presentation. “Benign sequestration of the lingual plate” is putatively caused by trauma. The lesion is generally only 3–5 mm in size, not painful, and occurs in healthy individuals, usually male.

Depending on the etiology, there is some variation in the clinical presentation. “Benign sequestration of the lingual plate” is putatively caused by trauma. The lesion is generally only 3–5 mm in size, not painful, and occurs in healthy individuals, usually male.

![]() In contrast, lesions associated with bisphosphonate use (both oral and intravenous preparations) occur in older patients being treated for osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, or metastatic cancer to the bones. The size of the exposed bone varies from several millimeters to several centimeters, and lesions may be painless or painful (eFig. 76-5.2A). Approximately 60% of lesions appear after oral surgical procedures such as a tooth extraction. Infection with Actinomyces or Eikenella are not uncommon.47

In contrast, lesions associated with bisphosphonate use (both oral and intravenous preparations) occur in older patients being treated for osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, or metastatic cancer to the bones. The size of the exposed bone varies from several millimeters to several centimeters, and lesions may be painless or painful (eFig. 76-5.2A). Approximately 60% of lesions appear after oral surgical procedures such as a tooth extraction. Infection with Actinomyces or Eikenella are not uncommon.47

![]() Osteoradionecrosis is associated with head and neck radiation, usually with doses greater than 60 Gys.50 Clinically, it resembles bisphosphonate-associated lesions (eFig. 76-5.2A).

Osteoradionecrosis is associated with head and neck radiation, usually with doses greater than 60 Gys.50 Clinically, it resembles bisphosphonate-associated lesions (eFig. 76-5.2A).

![]() See above for the differential diagnosis.

See above for the differential diagnosis.

![]() CT scans and dental imaging studies are useful for delineating extent of disease.

CT scans and dental imaging studies are useful for delineating extent of disease.

![]() The biopsy reveals necrotic bone usually with extensive bacterial colonization with/out abscesses.

The biopsy reveals necrotic bone usually with extensive bacterial colonization with/out abscesses.

![]() Once the bone is removed in “benign sequestration of the lingual plate,” the mucosa heals. The other conditions tend to be more severe, involve larger areas of necrotic bone, and are more difficult to treat; the bone exposure may be present for years. Management is directed at removal of necrotic bone, treatment of active infections, and reduction of symptoms. This may include using antimicrobial rinses (such as chlorhexidine), systemic antibiotics, nonsurgical sequestrectomy, debridement, surgical resection, and/or hyperbaric oxygen therapy.51,52

Once the bone is removed in “benign sequestration of the lingual plate,” the mucosa heals. The other conditions tend to be more severe, involve larger areas of necrotic bone, and are more difficult to treat; the bone exposure may be present for years. Management is directed at removal of necrotic bone, treatment of active infections, and reduction of symptoms. This may include using antimicrobial rinses (such as chlorhexidine), systemic antibiotics, nonsurgical sequestrectomy, debridement, surgical resection, and/or hyperbaric oxygen therapy.51,52

It is important to distinguish truly white lesions from ulcerated or necrotic lesions that usually have a creamy-yellow color.

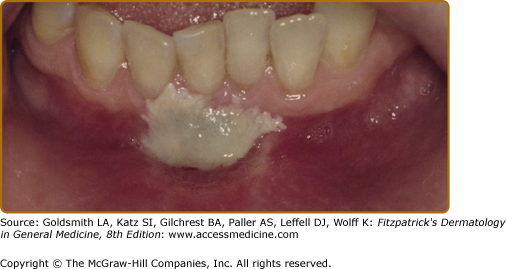

Many well-recognized oral lesions are white, ranging from developmental lesions such as white sponge nevus, to infections such as candidiasis, to immune-mediated disorders such as lichen planus (LP) and to frictional keratoses such as morsicatio mucosae oris (Table 76-3). Such lesions, with specific clinical and histologic findings, are not properly termed “leukoplakia.”

Developmental (Often Part of a Genodermatosis) |

|

Reactive |

|

Infectious |

|

Immune-mediated |

|

Neoplastic |

|

True leukoplakias tend to be well demarcated at least around part of the lesion, are frequently dysplastic at first biopsy, and carry a significant potential for developing into SCC over time. White sponge nevus and reactive white lesions are discussed online.

White sponge nevus is an extremely rare condition, inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. It affects the oral and genital mucosa, usually in a symmetric and often multifocal pattern, due to mutation in keratin K4 or K13 that results in keratin instability and abnormal keratin aggregation.53 Spontaneous mutations have been reported.

Patients develop poorly demarcated, diffuse, painless white plaques on the oral mucosa, usually the buccal mucosa and tongue, usually within the first two decades of life.21,54

Other conditions that may appear similar clinically include hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis, another rare mucosal disorder that occurs in a racial isolate in South Carolina,55–57 and pachyonychia congenita.58–60 Oral lesions of dyskeratosis congenita are true leukoplakias occurring in approximately 65% of patients and are usually dysplastic.61,62

Biopsy or exfoliative cytology is always indicated and shows perinuclear eosinophilic condensations (representing abnormal keratin aggregation) and distinguishes it from other mucosal disorders discussed below.

There is no treatment for white sponge nevus, although some have reported resolution with antibiotics, in particular tetracycline.63 It is postulated that tetracycline affects the keratinization process and inhibits epithelial proliferation.

These very common conditions are caused by very mild topical injury caused by smoking or other mild contact injury such as strong toothpastes and alcoholic mouth rinses. The following white lesions are in ascending order of severity of injury beginning with changes caused by intracellular edema and swelling to those resulting in keratoses.

Many dentists classify leukoedema as a developmental malformation but it is likely a reactive lesion. It occurs in 20%–70% with habits such as using tobacco, coca, or marijuana to >90% of dark-skinned individuals mainly because the whiteness of the lesion shows up more clearly on pigmented mucosa.54,64

Lesions are usually bilateral on the buccal mucosa or ventral tongue and consist of painless, fine grayish white, opalescent reticulations. They are not well demarcated, but diffuse. Stretching the mucosa completely eliminates these fine lines since this is not a keratotic lesion, but rather caused by intracellular edema of damaged superficial keratinocytes.21

Reticular LP may look similar but they are more densely white and do not disappear on stretching the mucosa.

A biopsy shows typical findings of keratinocyte edema or hydropic degeneration.

No treatment is necessary since these lesions are benign although advice on smoking cessation may be warranted.

This is a common oral condition, where the injury to the tissue is slightly more severe than in leukoedema causing actual degeneration and detachment of the superficial keratinocytes. The offending agents are mouthwashes and toothpastes that are caustic [in particular Listerine (Pfizer Pharmaceutical, NY) mouthwash that contains 27% alcohol as well as eucalyptol and menthol].

This is generally a condition of adults. Patients will often report that their mouth is “peeling.” Lesions present as painless sloughs of desquamated tissue that lie in thin ribbons on the mucosa and can be removed without pain or discomfort to the patient, with normal-appearing, pink underlying tissue.65 Since the keratinized tissues are somewhat protected from the adverse effects of such topical agents, it is generally the nonkeratinized tissues that are involved. A helpful sign is a background of leukoedema with faint reticulations.

While some bullosing disorders may form such sloughs, those lesions are almost always painful or sensitive, and may bleed. Lack of symptoms is key to the diagnosis of this condition coupled with the typical history.

A biopsy shows desquamating strips of surface keratinocytes.

Patients should discontinue the use of the offending dentrifrice, or change to a less caustic agent.

This is a yet more intense local factitial injury to the oral mucosa, caused by a chewing habit, leading to reactive keratosis and benign epithelial hyperplasia. It occurs in 3% of the population.66 Any other factitial injury either from an unusual habit, or the rough edge of an appliance may lead to a similar lesion.

MMO appears as white papules and plaques on either side of the linea alba on the buccal mucosa, lower labial mucosa, or the lateral tongue, usually caused by raking of the teeth over the mucosa.67 Patients may or may not be aware of this habit (especially if this is a nighttime habit). Lesions have a shaggy, rough surface, are poorly demarcated, and occasionally may show evidence of erythema and/or ulceration where the “chewing” has been more intense (eFig. 76-5.3A and 76-5.3B).

Candidiasis, some lesions of LP, hairy leukoplakia, and some leukoplakias and erythroleukoplakias may look similar but a biopsy will provide a definitive diagnosis. Such factitial injury may be superimposed upon an underlying condition such as dysplasia or LP, making the diagnosis even more challenging.

A biopsy shows varying degrees of parakeratosis with impetiginization and benign epithelial hyperplasia.

No further management is necessary. These lesions are benign and have no malignant potential. The use of night guards or appliances to break the habit has not been shown to be helpful.

BARK is a very common condition that was recently defined histologically. It occurs primarily on the keratinized mucosa of the gingiva and hard palate as a reaction to frictional trauma. It is the oral equivalent of lichen simplex chronicus.

BARK presents as poorly demarcated, painless white papules and plaques, often with a rough surface, usually less than 1 cm in greatest dimension (eFig. 76-5.4). The most common location is the retromolar pad (at the site of previously extracted wisdom teeth) and other areas where teeth have been extracted.68,69 It is not necessary for the opposing teeth to contact the mucosa, since crushing of food against the alveolar ridge that had been previously protected by a tooth is sufficient.

Leukoplakia, especially verrucous leukoplakia is a very important differential diagnosis and a biopsy should always be performed if the lesion shows signs of sharp demarcation or is extensive. More worrisome, verrucous leukoplakia, a dysplastic lesion, also has a rough surface and is usually greater than 1 cm.

A biopsy shows typical features of lichen simplex chronicus. BARK is closely related to MMO (described above), another frictional keratosis. It is possible that BARK being located on the keratinized mucosa that is closer in histology to the skin, takes on the more typical histologic characteristics of lichen simplex chronicus (LSC).

No treatment is necessary once the histopathologic diagnosis has been established. If a denture is the source of frictional irritation, this should be adjusted accordingly.

Nicotinic stomatitis is not caused by nicotine as its name suggests but rather by heat, usually from pipe smoking. A similar condition may be seen in patients who reverse smoke, that is, hold the lighted end of the cigarette in the mouth, as is the habit in some South Indian and Southeast Asian populations. It has also been noted in patients who habitually drink very hot beverages.

The palate of adult patients is the site most often affected. It is diffusely white with red, punctuate areas representing the openings of salivary ducts. It is usually not a painful lesion although severe cases may be sensitive to hot and spicy foods, and lesions are usually symmetric and diffuse.21,54

Leukoplakia and candidiasis of the palate may both mimic nicotine stomatitis.

A biopsy shows hyperkeratosis with benign epithelial changes and importantly, inflammation of excretory salivary ducts that exhibit squamous metaplasia. This diagnosis is difficult if the ducts are not included in the biopsy specimen.

Lesions may resolve if the habit is discontinued. The risk for malignant transformation has not been well documented. However, the development of raised, indurated areas should raise suspicion for malignant transformation.

This is a lesion that results from a combination of direct contact toxicity of the smokeless tobacco on the mucosa (early lesions), and from effects of carcinogens within the snuff, namely tobacco-associated nitrosamines (late lesions that represent true leukoplakias). Not all smokeless tobaccos are alike. Snuff may be moist or dry and in general moist Swedish snuff (“snus”) is lower in nitrosamines than moist and dry snuff from the United States.70 Toombak, snuff from Ethiopia, has the highest levels of nitrosamines of all.71 In many Asian countries, snuff and smokeless tobacco is mixed with other substances such as spices and importantly areca nut, which contains another potent carcinogen, the alkaloid arecoline.72

Over the last 10–15 years, there has been increased interest in using smokeless tobacco as a risk reduction measure in subjects who have difficulty discontinuing cigarette smoking because the risk of developing cancer (oral and other cancers) is reduced.73,74

The lesions are located where the snuff is placed, usually the mandibular sulcus/vestibule, between the teeth and the buccal mucosa. The area looks grayish white, opalescent, and wrinkled, often with fissures.21,54

Lesions are generally painless and poorly demarcated (eFig. 76-5.5).

The diagnosis includes leukoplakia, candidiasis, and BARK. Aspirin is much more caustic and causes necrosis and ulceration, rather than this delicate white lesion.

Biopsy reveals thin parakeratosis, intracellular edema, and devitalization of superficial keratinocytes. Any other agent that is locally irritating and slightly caustic may cause this clinical appearance.

Most early lesions are primarily caused by contact injury and are reversible if the habit is discontinued. However, the development of a dense white plaque or erythema may signal transformation to malignancy and these areas should be biopsied. The rate of malignant transformation is only 1%–2% compared with cigarette smoking.

Fungal infections are extremely common in the oral cavity and the most common causative agent is Candida albicans. Approximately 20%–30% of the population are carriers. In immumnocompromised hosts, other species such as C. tropicalis, C. dubliniensis, C. glabrata, and C. kruseii should also be considered, as some of these may be resistant to conventional therapy. Predisposing factors include hyposalivation (see Section “Xerostomia” and “Hyposalivation”), immunocompromise, topical steroid therapy (for treatment of oral lesions or as inhalers), and antibiotic therapy.

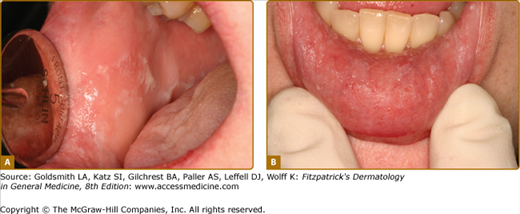

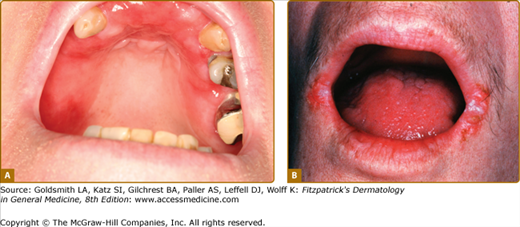

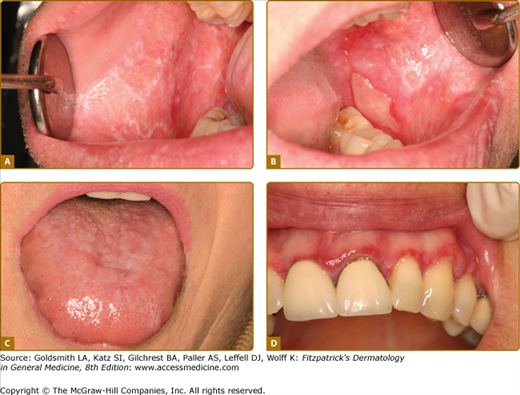

Oral candidiasis may present in various forms (Table 76-4) (Figs. 76-6A–76-6B).1,21 Lesions are almost always painful and dentures act as fomites.75 Although C. albicans is the most common pathogen in denture-associated candidiasis, C. glabrata is found in 30% of cases.76

Type | Clinical | Treatment |

Thrush/Pseudomembranous candidiasis | Curdy yellowish-white papules or plaques; may or may not scrape off Often synchronously on dorsum or tongue and palate so-called “kissing lesions” | Nystatin 1:100,000 iu/mL; swish and spit out 5 mL tid or qid Clortrimazole trochea 10 mg; suck on 1 troche tid or qid Ketoconazole 200 mg qd × 7-14 daysFluconazole 100 mg; take one tablet once a day × 3–10 days |

Erythematous/Atrophic candidiasis |

|

|

Hyperplastic candidiasis | Primarily white papules and plaques with minimal erythema; associated with mucocutaneous disease or hairy leukoplakia | See Thrush above |

Angular cheilitis | Fissured, weepy lesions at the corners of the mouth; often associated with Staphylococcus aureus | Mycostatin and triamcinolone cream; may need topical erythromycin |

Median rhomboid glossitis | Rhomboidal area in posterior midline of tongue, anterior to circumvallate papillae; maybe slightly depressed and erythematous, or raised | See Thrush above |

An important differential diagnosis is hairy or coated tongue. This is not a candidal infection, although cultures may grow Candida in carriers. These lesions are almost always painless and do not involve mucosa other than tongue dorsum, unusual for candidiasis. It is caused by hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue, with retention of keratinaceous debris as a result of hyposalivation and poor oral intake. Patients therefore are often ill, dehydrated, and on antibiotic therapy, further adding to the suspicion that the lesions represent candidiasis.

Culture is not particularly useful for diagnostic purposes since many individuals are carriers. However, culture is important if speciation or sensitivity is required, or to identify carriers prior to the start of long-term steroid therapy. A potassium hydroxide preparation using scrapings from oral lesions is a good way to identify infection. Biopsies show typical candidal organisms.

Patients who have dry mouths from polypharmacy or substantial damage to salivary glands (such as from radiation) are prone to develop recurrent candidiasis and are particularly difficult to manage. Nystatin rinses and clotrimazole troches contain caries-inducing sugars and should be used long-term only with careful monitoring by the dentist. The use of cholinergic agents such as pilocarpine or cevimeline helps to restore some secretory function of salivary glands and may reduce the frequency of candidiasis.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infections in the oral cavity may present as a primary infection (infectious mononucleosis). Hairy leukoplakia is an unusual presentation of recrudescent EBV in the oral cavity, where this normally lymphotropic virus is present within the epithelium.

This manifests as a painless, white plaque usually located on the lateral border of the tongue in immunocompromised patients, and in particular, those with HIV/AIDS and after organ transplantation.77,78

Typically, these present as white linear lesions running perpendicular to the long axis of the tongue but when more advanced, may extend onto the dorsum and present as a plaque (Fig. 76-7). Lesions are usually asymptomatic and usually superinfected with Candida. Infrequently, hairy leukoplakia has been reported in healthy individuals.79

Lesions of MMO and candidiasis often occur on the lateral tongue and may appear similar.

Both cytologic smears and biopsies show characteristic findings and the presence of EBV can be confirmed by in situ hybridization.

The presence of hairy leukoplakia may be the first indication that a patient is infected with HIV. In patients with established HIV/AIDS, hairy leukoplakia is usually associated with a low CD4 count and high viral load.77 Treatment with an antifungal medication (see Section “Candidiasis”) will resolve the associated candidiasis and treatment with antiretroviral therapy results in resolution.

Oral LP is an immune-mediated disorder and an interface stomatitis characterized by T-cell destruction of the basal cells of the epithelium, possibly as a result of altered antigen presentation on these cells, mediated by TH1 cytokines. Interferon-α production is thought to mediate lesions involving the oral cavity only while TNF-α may mediate systemic disease.80 Whether this is a disease in and of itself or whether it represents a “final common pathway” of mucosal reaction is unclear at this time. Many local and systemic conditions predispose to the development of such “lichenoid lesions” in the oral cavity. The term “lichenoid” used here to describe reticulated, often erythematous and/or ulcerated lesions, usually bilateral and symmetric. Unfortunately, many erythroleukoplakias that are by definition red and white lesions but usually without significant reticulation are also clinically described as “lichenoid” by some investigators, causing confusion and leading to the concept of LP as a premalignant lesion.

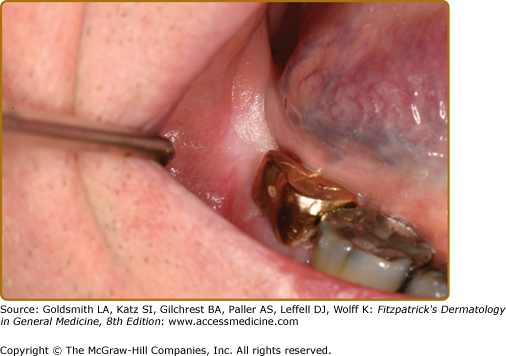

Local lichenoid reactions may develop as a result of contact injury to amalgam restorations or cinnamic aldehyde from chewing gum. Medications implicated in the development of oral LP include antihypertensive agents (especially hydrochlorthiazide), some hypoglycemic agents, allopurinol, sulfasalazine, carbamazepine, and the new biological agents.80–82 It is often impossible to differentiate either clinically or histologically, between lesions of idiopathic LP and lichenoid hypersensitivity reactions.83

Other conditions associated with oral lichenoid lesions include hepatitis C in Mediterranean races and this is associated with HLA-DR684,85; chronic graft-versus-host disease, and lupus erythematosus.86,87

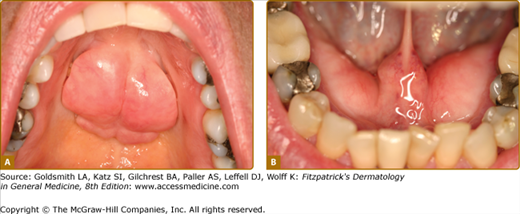

Oral LP occurs in 1%–2% of the population in the United States and affects females more than males, usually those in the fifth decade of life and older. Three clinical forms are noted—(1) keratotic/reticular, (2) erythematous/erosive, and (3) ulcerative—and these often occur in combination.21,54 The most recognizable is the keratotic/reticular form (Wickham striae) that is usually not painful. This is symmetric in distribution and reticulations almost always occur on the buccal mucosa and tongue although any oral mucosal site may be affected (Figs. 76-8A and 76-8B). Lesions on the dorsum of tongue tend to be subtle and more papular with atrophy of filiform papillae giving the tongue a white cast and smooth appearance (Fig. 76-8C). The erythematous or erosive form is usually painful and this is particularly common as a primary presentation on the gingiva (clinically desquamative gingivitis).88 LP on the gingiva is also noted in the gingival–genital syndrome.89 Ulcerative LP usually occurs in association with the other two forms. The finding of intact blisters (bullous LP) is rare in the oral cavity because it is a trauma-intense environment. Concomitant skin involvement is noted only in 10%–15% of patients.

A controversial entity is the so-called “plaque-type LP.” If this lesion occurs as a unilateral plaque without reticulations, it should be considered a leukoplakia. If it occurs within an established, typical symmetric oral LP, it should be considered “leukoplakia developing within LP.” In either case, biopsy is indicated to exclude dysplasia or malignancy.

Several scoring systems have been developed for evaluating the severity of disease but none are universally accepted.90–92

Many conditions may result in the development of LP and lichenoid reactions. However, the most important is erythroleukoplakia. It can be differentiated from oral LP in that it is not usually definitively reticulated (although it may have subtle linear areas), is usually asymmetrically distributed, and often presents at a high-risk site for cancer such as the ventral tongue unilaterally. It is strongly associated with dysplasia and carcinoma (see below). Other lesions include candidiasis and contact stomatitis such as to chewing gum.

Chronic ulcerative stomatitis is an entity that resembles erythematous/erosive LP but is associated with antibodies directed against δNp63α.93 Direct immunofluorescence studies reveal nuclear binding of keratinocytes in the basal and lower one-third of the epithelium. Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) G can be detected using guinea pig esophagus as substrate and an ELISA is now available.94

The reticulated white areas on the buccal mucosa may sometimes resemble MMO. Erythematous LP lesions on the gingiva are often indistinguishable from other diseases presenting as desquamative gingivitis such as mucous membrane pemphigoid, hypersensitivity reaction, or plasma cell gingivitis. Pure ulcerative lesions without reticulations are more likely to be aphthous ulcers.

Diagnostic histopathologic findings for oral LP, are squamatization of basal cells and a lymphocytic band at the interface. Direct immunofluorescence studies show shaggy fibrinogen and often IgM at the interface and IgM staining of colloid bodies.

Management of oral LP and lichenoid lesions involves pain control and treatment with topical steroids and other anti-inflammatory agents (Table 76-1).95 Gingival lesions are effectively treated with topical steroids held in a stent. Systemic therapy with prednisone (at 1 mg/kg for 1 week with a fairly rapid taper) or hydroxychloroquine should be instituted in severe cases and topical therapy started concomitantly.

Localized, unliateral lesions may respond to removal of dental restorations and a short course of topical steroids. Disease remission occurs in <10% of cases.

The rate of malignant transformation (often given as 1% every 5 years) is controversial because some studies do not correct for confounding factors such as smoking, while other included erythroleukoplakias, leukoplakias (diagnosed as “plaque-type” LP), and proliferative leukoplakia in the group of “lichenoid” lesions. Classic, bilaterally symmetric, reticulated LP has a very low malignant potential.96

This is one of the more challenging diagnostic entities of oral mucosal disease. Leukoplakia is defined as a “white plaque of questionable risk having excluded other (known) diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer.”97 It is a clinical diagnosis only and modified once the histopathologic diagnosis is known. For example, what may appear to be a provisional diagnosis of leukoplakia on the buccal mucosa may histopathologically prove to be MMO as a final definitive diagnosis. Frictional keratosis is NOT a leukoplakia and the only two histologically well-defined frictional keratoses are (1) MMO and (2) BARK. Because frictional injury is very common in the oral cavity and usually presents as a hyperkeratosis, it is likely that many so-called leukoplakias actually represent nonspecific frictional keratoses that are not MMO or BARK.

Leukoplakias occur in 2%–4% of the population.98

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree