Bilateral Transverse Rectus Abdominus Myocutaneous Flaps

Onelio Garcia Jr.

The number of patients undergoing bilateral mastectomies in the United States has significantly increased over the last 10 years. According to statistics from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1), 92,921 mastectomies were performed in the United States in 1996, of which 1,455 (1.5%), were bilateral. In contrast, in 2006 the agency reported 69,525 mastectomies, of which 6,747 (9.7%) were bilateral. A review of the surgical logs at the University of Miami Hospitals revealed that in the year 2000 there were 133 mastectomies performed at the institution, and only 4 were bilateral (3.1%). At the same institution in the year 2008 there were 136 mastectomies, with 17 bilateral (12.5%). In 2009, 37% of the mastectomies performed at my primary institution were bilateral.

Statistics from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2) show that 86,424 breast reconstructions were performed in 2009. Transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM) flap reconstructions accounted for approximately 10,000 of these. Based on the percentage of bilateral mastectomies, bilateral TRAM flaps accounted for approximately 1,500 to 3,000 of the breast reconstructions performed in 2009.

Expander-implant reconstructions remain the most common method of breast reconstruction in the United States, accounting for approximately 60% of all reconstructions (2). In spite of these numbers, it is generally accepted by plastic surgeons that autologous tissue breast reconstructions yield the most natural and aesthetically pleasing results (3,4,5,6,7). Prior to the era of perforator flaps and similar techniques that do not disrupt the integrity of the abdominal wall, the TRAM flap (8) use to be the gold standard because of its versatility, reliability, and relatively low associated morbidity. Bilateral TRAM flaps however, remain an efficient method for reconstruction of bilateral mastectomies since there is usually enough donor tissue to create both breast mounds with excellent symmetry and minimal morbidity (9,10).

Available Techniques for Bilateral Transverse Rectus Abdominus Myocutaneous Flaps

One of the most appealing qualities of the TRAM flap is its versatility. Plastic surgeons can create beautiful breast reconstructions using any one of several TRAM flap techniques. Generally one has to choose between a pedicled flap (conventional TRAM) or a free microvascular transfer of the flap (free TRAM). There are pros and cons with both techniques, which must be taken into consideration when planning the breast reconstruction.

Conventional TRAM flaps are technically simpler and can usually be performed faster than the free TRAM flaps. This is particularly advantageous in immediate bilateral reconstructions, where the patient is subjected to lengthy anesthesia time periods that include bilateral mastectomies with possible sentinel node exams followed by bilateral harvesting of the TRAM flaps and then breast mound reconstructions. The conventional TRAM flap can be performed in most institutions without the need for specialized equipment or personnel experienced in microvascular surgical techniques. In addition, free TRAM flaps are associated with less donor-site morbidity (11,12) since less muscle is removed (13), and their blood supply is usually more robust (14), although in bilateral conventional TRAM flaps the blood supply is usually very reliable since it does not cross the midline. Contraindications to free TRAM flap breast reconstruction may include damaged or small recipient vessels or a severely irradiated chest wall.

Several authors consider the free TRAM a better choice for bilateral breast reconstruction (9,10,11,15,16); however, I have not found that to be the case. My experience in hundreds of TRAM flap operations over a 25-year period is that both the free TRAM and the muscle-sparing conventional TRAM flaps are equally effective in reconstructing bilateral mastectomy defects and creating aesthetically pleasing breasts with relatively low morbidity. In my practice I have found the incidence of abdominal bulges to be 5% following TRAM flap reconstructions, and it is similar for conventional and free TRAM flaps. These findings are also well supported in the literature (13). It seems that abdominal bulges following TRAM flap reconstructions are related to the integrity of the donor-site repair and not to the technique of flap transfer. I have found the incidence of true hernias to be quite low, although it is reported in the literature as 1% to 10% of cases. As previously mentioned, both the bilateral conventional TRAM and the free TRAM flaps are very reliable from a vascular point of view, and for that reason flap loss in bilateral cases is a less common occurrence.

Bilateral Conventional Transverse Rectus Abdominus Myocutaneous Flaps

There are several variations of the conventional TRAM flap available for both unilateral and bilateral reconstructions. First, one has to decide on the amount of muscle to be taken with the flap. One can transfer the complete rectus muscle as the pedicle or the medial two thirds (approximately 60%) of the muscle containing the vascular supply (muscle-sparing TRAM flap). Second, one has to decide whether to transfer the flap to the ipsilateral or contralateral side.

Taking the complete rectus muscle with the vascular pedicle in bilateral reconstructions is easier and faster than the muscle-sparing technique; however, this method creates greater donor-site deformity and makes it more difficult to close the donor-site primarily. Transferring the complete rectus muscle with the pedicle in bilateral reconstructions also can create significant

epigastric fullness, which can blunt the medial portion of the inframammary fold and diminish the aesthetic result.

epigastric fullness, which can blunt the medial portion of the inframammary fold and diminish the aesthetic result.

Although ipsilateral transfer of the flap is advocated by some plastic surgeons (17), it necessitates creating two tunnels with wider undermining of the superior abdominal flap. This can cause more disruption of the medial inframammary folds, and there can be more potential for devascularization of the abdominal flap.

For bilateral conventional TRAM flap reconstructions I currently perform a muscle-sparing technique, which includes almost the medial two thirds of each rectus muscle. The lateral one third as well as a small medial strip of rectus muscle are left in place. Even though the lateral one third of the muscle that remains is not functional, I am in agreement with other authors (13,18) who believe that it strengthens the donor-site repair and makes the closure easier.

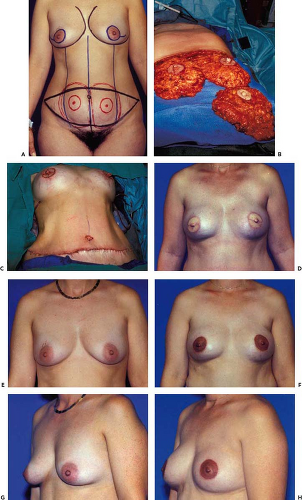

Whenever time permits, smokers are asked to stop smoking at least 2 weeks preoperatively. Medications such as aspirin that alter platelet function are stopped 1 week prior to surgery. The patient is kept on a liquid diet for 48 hours prior to surgery and takes a laxative on the day before surgery. The patient is marked in the standing position using a surgical marking pen, preferably on the afternoon prior to surgery (Figs. 54.1A to 54.4A). All patients are fitted with sequential pneumatic

compression stockings in the preoperative holding area as prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered in the preoperative holding area. As soon as the patient is under anesthesia an indwelling Foley catheter is placed. A warming blanket is used over the lower extremities, and the intravenous fluids are warmed. Significant anesthesia time can be saved by performing the surgical prepping and draping in a manner that can accommodate both the mastectomy surgery and the TRAM flap procedure.

compression stockings in the preoperative holding area as prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered in the preoperative holding area. As soon as the patient is under anesthesia an indwelling Foley catheter is placed. A warming blanket is used over the lower extremities, and the intravenous fluids are warmed. Significant anesthesia time can be saved by performing the surgical prepping and draping in a manner that can accommodate both the mastectomy surgery and the TRAM flap procedure.

The technique for bilateral conventional TRAM flap elevation is somewhat similar to a unilateral TRAM flap and is also well described throughout this book. The previously marked incision areas are infiltrated with a dilute epinephrine solution (1 mg of epinephrine1:1,000 L of normal saline). The dissection can be performed with Bovie cutting electrocautery, although recently I have found the harmonic scalpel to work quite well in a wet field and to achieve equal hemostasis to the Bovie with minimal thermal tissue damage. The incision around the umbilicus is made first, and the umbilicus is left on its vascularized umbilical stalk. An incision is then made on the superior marked border of the flap and extended through the subcutaneous tissue slightly beveling it cephalad to the level of the fascia. The superior abdominal flap is elevated like an abdominoplasty flap to the costal margins laterally and medially to the level of the xiphoid. In the epigastric area the dissection is not extended laterally beyond the lateral edge of the rectus sheath. A tunnel is created between the abdominal flap and the mastectomy defects. The tunnel should be of sufficient dimensions to accommodate the surgeons’ hand and should be kept in the midline with medial communications with each mastectomy site. The tunnel communications are created as medial as possible to avoid significant disruption of the medial portion of the inframammary folds. The creation of only one tunnel that communicates with both mastectomy defects should preserve most of the inframammary folds. Use of a fiberoptic lighted retractor facilitates the tunnel dissection.

Attention is now directed to making the previously marked lower abdominal incision and extending it to the level of the fascia. A midline incision from the umbilicus toward the pubic area divides the lower abdominal flap into two equal portions. The lower abdominal flaps are elevated from medial to lateral until the medial perforators are encountered on each side and then from lateral to medial until the lateral row of perforators is encountered. An incision is now made with the Bovie into the anterior rectus sheath just lateral to the lateral row of perforators and extended inferomedially to just below the level of

the arcuate line. The muscle is then split longitudinally in the direction of its fibers, and the muscle lateral to this split stays in place. Through this muscle rent, the deep inferior epigastric vessels are identified, dissected with a fine right-angle clamp, and individually ligated by applying two small hemoclips to each of the veins and two medium hemoclips to the artery prior to dividing them. A more extensive dissection of the inferior epigastric vessels is recommended in patients with high risk factors for vascular compromise, such as obesity, smoking, or diabetes in case that supercharging (19) of the flap may be necessary. An incision into the anterior rectus sheath is performed with the Bovie cutting electrocautery on both sides of the midline just medial to the medial perforators. The underlying rectus muscle is split longitudinally, keeping a small medial strip of muscle in place. The rectus muscle to be included with the flap is divided using Bovie electrocautery just below the level of the arcuate line. Leaving the inferior part of the rectus and pyramidalis muscles intact is useful for achieving a sound repair of the inferior abdominal donor site. The elevation of the muscle pedicle from the posterior sheath proceeds from the site of the inferior muscle division to the costal margin, dividing the collateral vessels and intercostal nerve supply along the way and leaving the lateral one third of the muscle intact within the sheath (Fig. 54.5). The lateral rectus muscle is divided above the costal margin. The exact location of the superior epigastric vessels is confirmed by pencil Doppler, and the medial muscle surrounding the vessels is left intact. In

immediate reconstructions the mastectomy specimen is used as the model for flap contouring on the abdomen (Figs. 54.1B to 54.3B) as previously described (20,21). This method accurately replaces the breast volume lost by the mastectomy and precisely fills the skin envelope to its original volume and shape (Figs. 54.1F, H, 54.2F, and 54.3D). The contralateral flap is then created as a mirror image in bilateral reconstructions. This method of performing the shaping and tailoring functions on the abdomen allows the surgeon to only transfer the volume of flap to be retained, thus keeping the tunnel dimensions to a minimum. Since the flap has been contoured to closely resemble the specimen, all that is needed is proper flap orientation after transfer to create a postoperative result that closely resembles the preoperative breast appearance (Figs. 54.1F, 54.2F, and 54.3D). Only one or two sutures are necessary to tack the flap to the pectoralis fascia to maintain orientation.

the arcuate line. The muscle is then split longitudinally in the direction of its fibers, and the muscle lateral to this split stays in place. Through this muscle rent, the deep inferior epigastric vessels are identified, dissected with a fine right-angle clamp, and individually ligated by applying two small hemoclips to each of the veins and two medium hemoclips to the artery prior to dividing them. A more extensive dissection of the inferior epigastric vessels is recommended in patients with high risk factors for vascular compromise, such as obesity, smoking, or diabetes in case that supercharging (19) of the flap may be necessary. An incision into the anterior rectus sheath is performed with the Bovie cutting electrocautery on both sides of the midline just medial to the medial perforators. The underlying rectus muscle is split longitudinally, keeping a small medial strip of muscle in place. The rectus muscle to be included with the flap is divided using Bovie electrocautery just below the level of the arcuate line. Leaving the inferior part of the rectus and pyramidalis muscles intact is useful for achieving a sound repair of the inferior abdominal donor site. The elevation of the muscle pedicle from the posterior sheath proceeds from the site of the inferior muscle division to the costal margin, dividing the collateral vessels and intercostal nerve supply along the way and leaving the lateral one third of the muscle intact within the sheath (Fig. 54.5). The lateral rectus muscle is divided above the costal margin. The exact location of the superior epigastric vessels is confirmed by pencil Doppler, and the medial muscle surrounding the vessels is left intact. In

immediate reconstructions the mastectomy specimen is used as the model for flap contouring on the abdomen (Figs. 54.1B to 54.3B) as previously described (20,21). This method accurately replaces the breast volume lost by the mastectomy and precisely fills the skin envelope to its original volume and shape (Figs. 54.1F, H, 54.2F, and 54.3D). The contralateral flap is then created as a mirror image in bilateral reconstructions. This method of performing the shaping and tailoring functions on the abdomen allows the surgeon to only transfer the volume of flap to be retained, thus keeping the tunnel dimensions to a minimum. Since the flap has been contoured to closely resemble the specimen, all that is needed is proper flap orientation after transfer to create a postoperative result that closely resembles the preoperative breast appearance (Figs. 54.1F, 54.2F, and 54.3D). Only one or two sutures are necessary to tack the flap to the pectoralis fascia to maintain orientation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree