div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

51. Circumcision: Avoidance and Treatment of Complications

Keywords

CircumcisionLichen sclerosusBuried penisMeatal stenosisUrethrocutaneous fistulaUrethral injuryPenile reconstruction51.1 Introduction

Circumcision has been practiced in large numbers for millennia. Early Egyptian paintings and mummies have shown that the technique has been practiced as early as 4000 BC [1] and in 2007 the World Health Organisation estimated that 30% of the world’s adult male population had been circumcised [2]. One might have thought that, given how long we have been performing this operation and the number of times it has been done, we might have perfected the technique by now. Not a bit of it. Any genitourinary tertiary referral centre will be all too familiar with patients referred in because the circumcision has not been successful or worse [3]. This may be due to poor hygiene or technique, but, occasionally, it can be a technically difficult operation, either due to the severity of the pathology, particularly lichen sclerosus (LS) , or occult anatomical variations, for example some patients with a forme fruste of hypospadias have a gossamer urethra which is more liable to injury [4]. Other anatomical variations, such a buried penis with mega-prepuce, may not be hidden but the signs can be subtle to the inexperienced [5]. Rare conditions such as pilonidal sinus of the penis require amendments to the technique [6]. Similarly obese adults and paediatric patients require a more careful approach due to the tendency of the penis to become buried in the supra-pubic fat pad [7].

The most common reason that circumcision is performed, however, is for religious and cultural reasons. Most consultant genitourinary surgeons, including the authors of this chapter, have little experience of this as it is usually performed by a trained religious practitioner, for example a Mohel in the Jewish faith, a trained nurse, operative or general practitioner. This chapter, therefore, will look at the way to deal with the complications of religious and cultural circumcision and how to perform a circumcision for medical indications, in a way to avoid or at least minimise the risk of complications.

51.2 Medical Indications for Circumcision

The most common indication is for phimosis secondary to lichen sclerosus [8] although it can also help other forms of glans inflammation, such as Zoon’s balanitis [9]. Circumcision is likewise advised in those few adolescents and adults with a persistent congenital phimosis or a relative phimosis (a foreskin which will retract when the penis is flaccid but is not slack enough to allow painless retraction when the penis is erect) to allow hygiene and painless intercourse [10]. Preputioplasty is an alternative for this group. Circumcision is performed for malignancy and pre-malignant change, not only of the foreskin, but also the glans, as PeIN (Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia ) of the glans can regress after removal of the foreskin [11]. It has increasingly been used as prophylaxis against sexually transmitted diseases, particularly HIV in those areas where the incidence is high, e.g. sub-Saharan Africa [2]. Rarely it is required to stop repeated infections of the foreskin [9] and has been also advocated for the management of recurrent urinary tract infections in boys, although a recent meta-analysis found little to justify its routine use for this indication [12]. It is indicated in the very rare cases of pilonidal sinus of the penis where the technique needs to be modified to remove the hair containing sinuses [6]. The foreskin in penile lymphoedema can be so large and unsightly, that circumcision is beneficial. In mild cases circumcision alone can suffice, but with more severe cases the penile shaft and scrotum can also require debulking with or without skin grafting [13].

51.3 When Not to Operate

Circumcision can be life-saving or curative of disabling symptoms, but the consequences of complications can be tragic. The best way to avoid complications is not to operate without good cause, especially in children with phimosis.

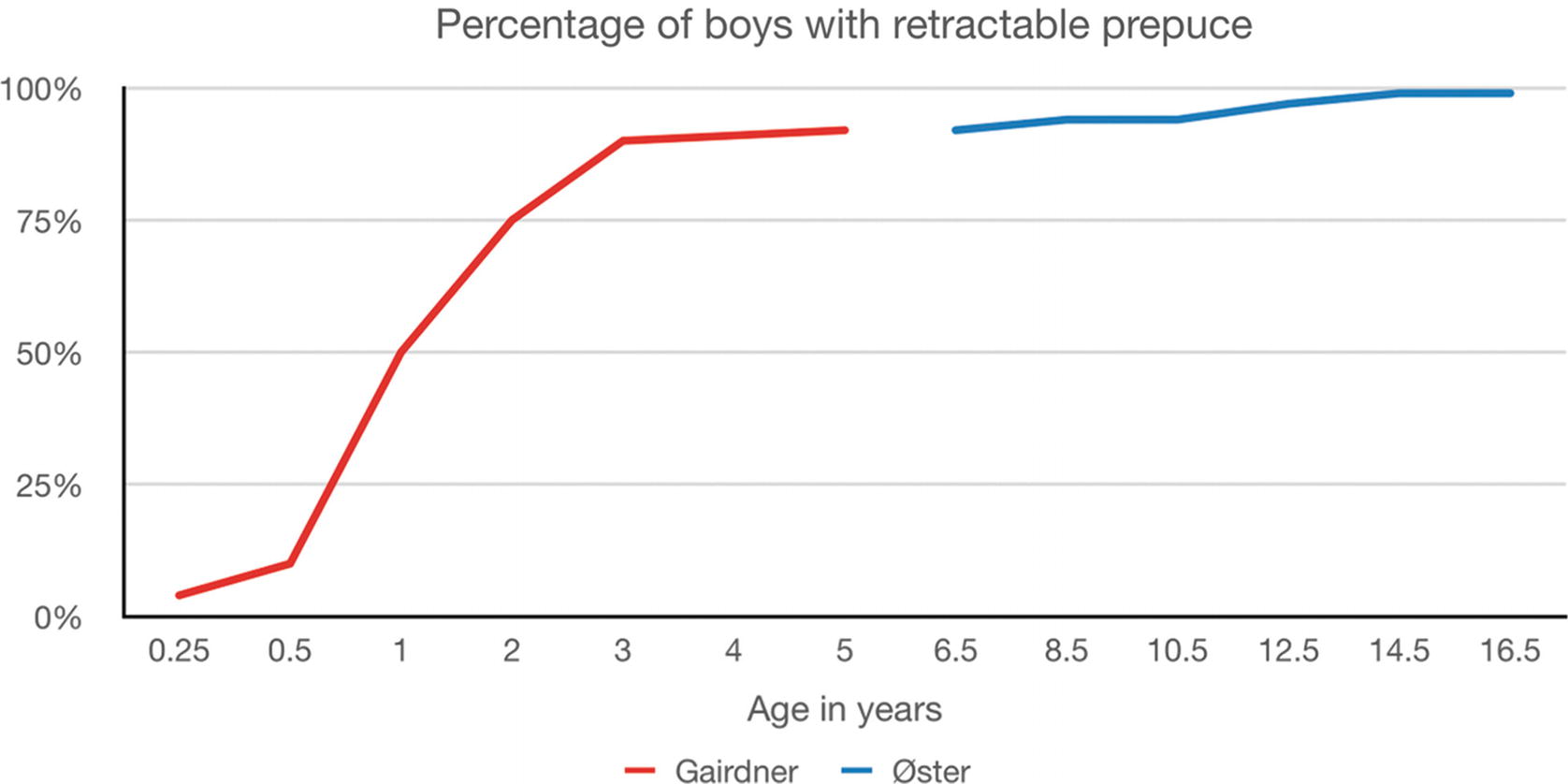

The percentage of boys with a retractable foreskin as they get older

51.3.1 Congenital Megaprepuce and Buried Penis

This relatively rare condition is frequently referred to urologists for treatment of phimosis by general practitioners. The key to the diagnosis is awareness of the paucity of shaft skin, and, in the case of congenital megaprepuce, the typical penoscrotal swelling with micturition. Urine can frequently be expressed by pressure applied in this area [16]. This is due to an extensive sac formed by a very large, redundant, inner prepuce, trapped by short, phimotic penile shaft skin. Circumcision, under these circumstances, is disastrous as it converts a congenital megaloprepuce into a trapped penis. In this case penoplasty is required, where every millimetre of shaft skin is preserved and, if necessary, the shaft is partially covered with inner preputial skin. Surgeons seeing paediatric patients for penile problems should familiarise themselves with this condition for fear of inappropriately removing what little shaft skin is available.

51.4 Complications of Circumcision

It is a fair adage that anything that can go wrong will go wrong (Murphy’s law attributed to John Stapp). The reported complications of circumcision bear testament to that law. They include death, bleeding, infection, sepsis, loss of part or all of the penis, taking too much or leaving too much inner preputial or penile shaft skin, meatal stenosis, urethral injury, urethrocutaneous fistula, poor cosmetic outcome, lymphoedema of the penis, particularly the remaining inner prepuce, decreased sensitivity of the glans, inclusion dermoid cysts, failure to expose the corona by releasing preputial adhesions or the formation of skin bridges. In addition, in cases where the operation has been performed to treat lichen sclerosus, it may fail to halt the progress of the condition, particularly in the obese.

When looking at the complications of circumcision there is obviously a difference between surgery in underdeveloped countries, frequently done by lay practitioners or nurses in a rural setting and surgery performed by trained urological surgeons under aseptic conditions with ready access to emergency care in the event of complications. The incidence of complications and their severity are so different that it is difficult to compare them in any one paragraph about a particular complication. That is not to say that severe complications aren’t reported in major surgical centres in affluent countries, just that they are less frequent by an order of magnitude although some, like tetanus [17] are not seen when surgery is done under aseptic conditions in a vaccinated community.

51.4.1 Circumcision in Developing Countries

In parts of the world, circumcision is performed as a ‘right of passage’ to manhood by lay practitioners in a rural environment. Under these circumstances severe infections including tetanus [17] are not uncommon and can be devastating or lethal. Meel (2010) [18] reported 25 deaths in a single large regional hospital in the Mthatha district of South Africa during the 2 year period 2005/6. The average age of the deceased was 17.6 years with the youngest being 12. Appiah et al. (2016) [19] reported 72 cases of circumcision related injuries during an 18 month period referred in to a single teaching hospital in Ghana. 78% of the complications were urethrocutaneous fistulae with 3 (7%), complete amputations. The mortality, however, seems lower than in the South African series, probably because the majority of these operations were performed by nurses in a rural hospital setting.

51.4.2 Complications in Developed Countries

Weiss et al. (2010) [20] reported a systematic review of circumcisions in male neonates, infants and children. He reviewed 52 papers from 21 countries which included sufficient information to estimate the frequency of adverse events. Retrospective analysis of the complications of child circumcision undertaken by medical providers gave a range of serious adverse events from 0% to 2.5%. Talini et al. (2018) [3], however, reported that, in a total of 2441 circumcisions in Brazil, 3.27% required surgical intervention for complications and Thorup et al. (2013) [21] reported a 5.1% significant complication rate when late complications were included. Comparison between different series is difficult due to the lack of standardised collection and reporting of data.

51.4.3 Death

Death following circumcision is fortunately very rare. Nevertheless about 16 deaths a year were reported in England and Wales from 1942 to 1947 mainly from anaesthetic complications, bleeding and infection [14]. The significance of bleeding in small babies should not be underestimated. The circulating blood volume of a 3.4 kg neonate is only about 300 ccs so what would be a relatively small bleed in an older child can exsanguinate a newborn baby. Although rare, in this day and age in affluent countries with a good health care system, fatalities are still occasionally reported, so this eventuality must be taken into consideration in the decision if and where to operate [22]. Furthermore, for every death there are usually several near misses [22] so the mortality rate always underestimates the incidence of severe complications.

51.4.4 Infection

Local infections are usually responsive to antibiotics and heal well without the necessity for surgical intervention. Nevertheless, even in a hospital environment, rare cases of severe infection including necrotising fasciitis have been reported [23] and patients and parents should be advised to seek medical help urgently if there are signs of systemic infection (sepsis) or spreading cellulitis. Prophylactic antibiotics have not been shown to be beneficial, and are not free of morbidity. In a non-randomised study of 84,226 patients, of whom 10.6% had received surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, Chan et al. (2017) [24] showed there was no reduction in the rate of surgical site infection by using prophylactic antibiotics (p = 0.5), but, not surprisingly, a significantly higher rate of a peri-operative allergic reactions (p = 0.0004).

51.4.5 Taking Too Much or Too Little Shaft Skin or Inner Foreskin

It is self-evident that this should be an avoidable complication, unless done deliberately as necessitated by the severity of the initial pathology e.g. for malignancy or severe lichen sclerosus . Taking too little is obviously better than taking too much as more can be taken at a later date. Equally there is no real reason why it cannot be judged accurately. The key is to judge where to place the inner and outer incision lines.

51.5 Technique of Circumcision: One Way to Perform a Circumcision

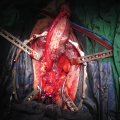

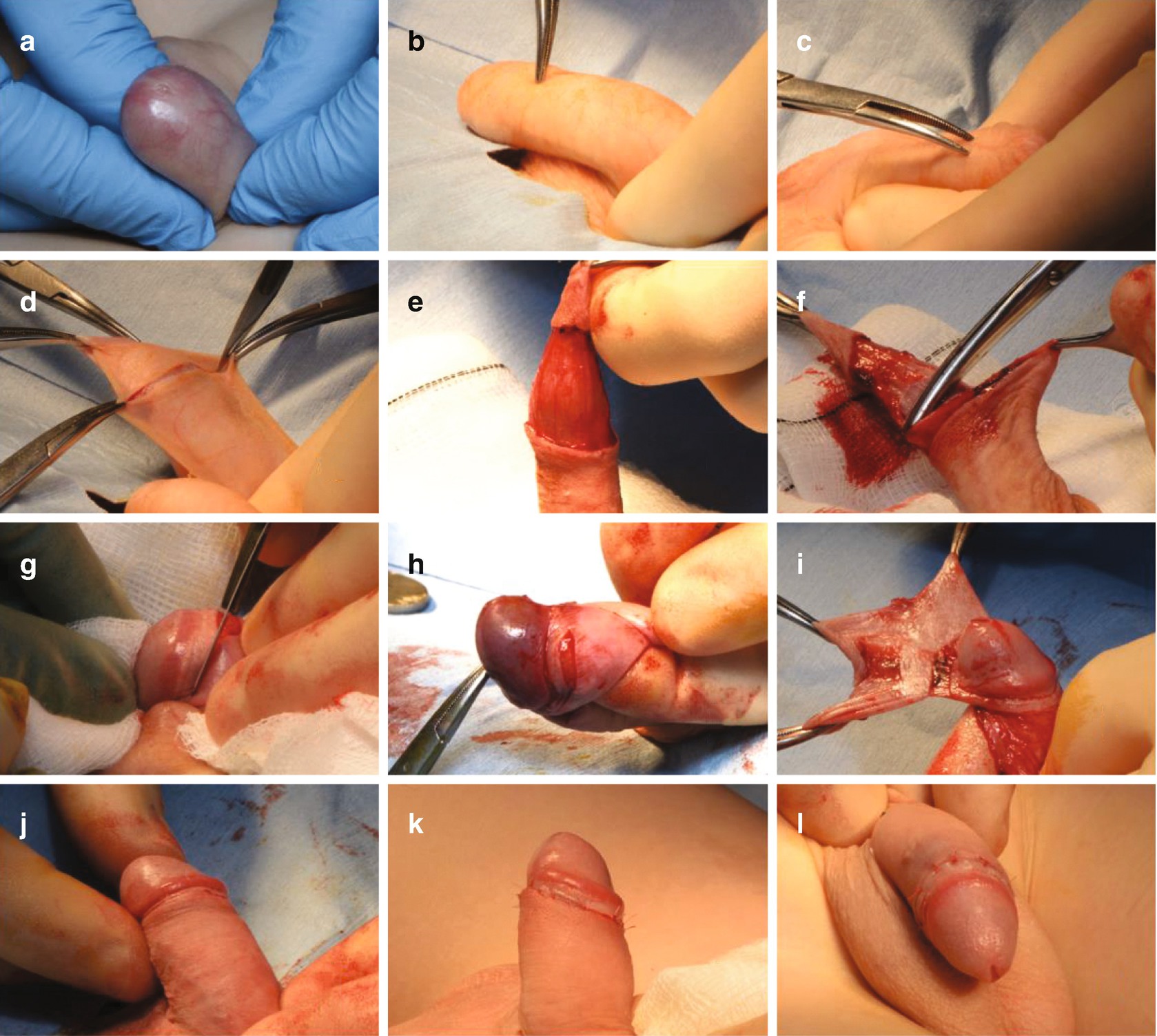

A technique of circumcision. (a) The penis of a child with a pinhole phimosis caused by lichen sclerosus. (b) The dorsal shaft is marked with the base of the penis pushed against the symphysis pubis. (c) The line of the corona is carried around the penis ventrally and marked in the midline. (d) 2 further clips are placed at the tip of the foreskin at 6 and 12 o’clock and straight incision made from just inside the proximal pair of marking clips on both sides. These clips are then removed and the incision completed circumferentially. (e) This leaves the shaft skin perfectly shaped to match the inner preputial skin, later. (f) The dartos is cut in the same line. (g) The inner preputial skin is scored about 5 mm from the corona. (h) On the ventral side this is made easier by placing a finger behind the prepuce to stabilise the penis and make it easy to score the inner prepuce precisely. (i) The foreskin is held well away from the urethra which is protected whilst the foreskin is removed. (j) The inner prepuce and shaft skin should match perfectly. (k) Fine 6/0 (5/0 in adults) dissolvable sutures complete the operation after bipolar haemostasis. (l) Dorsal view of the finished operation

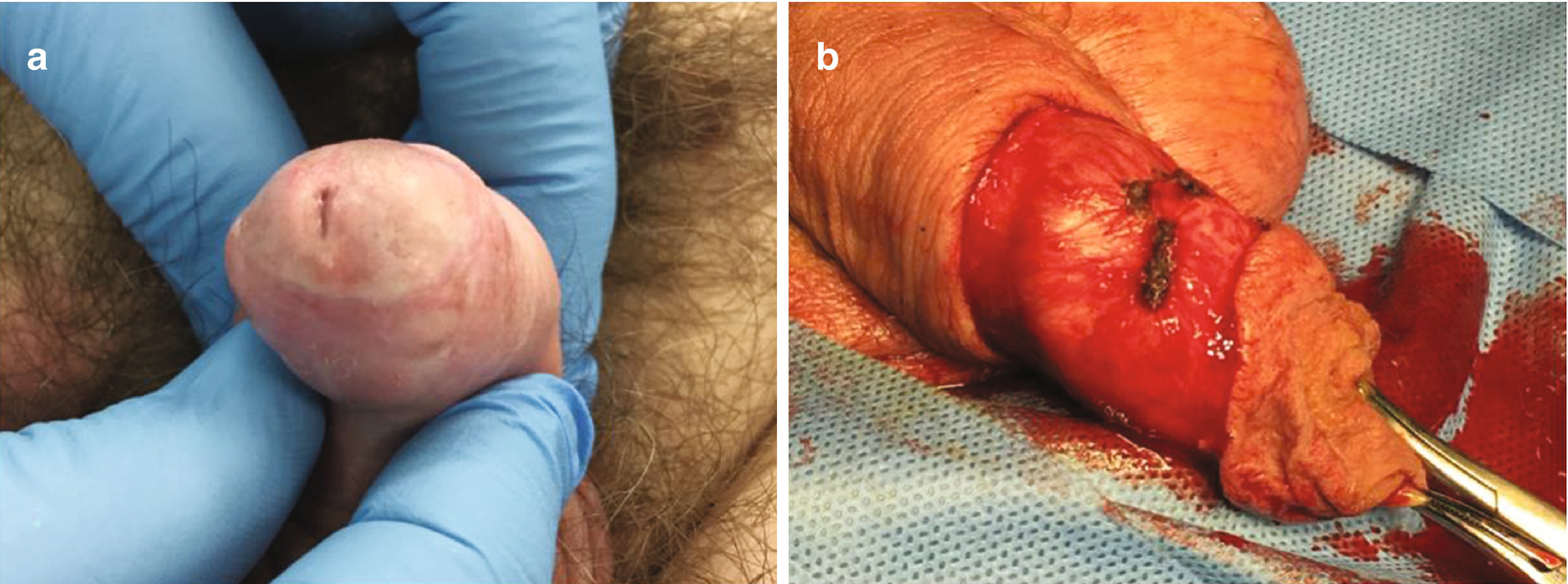

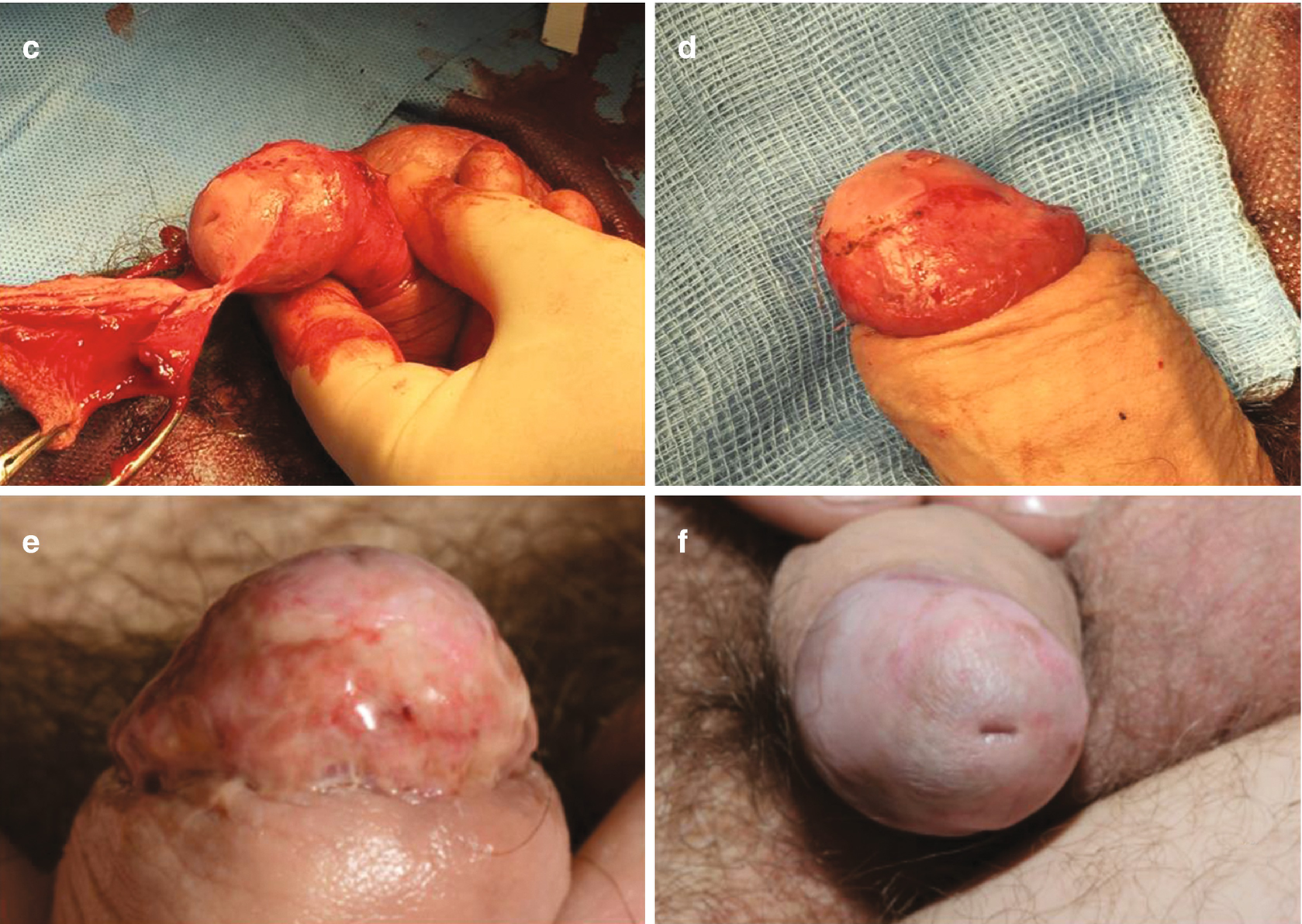

51.6 Lichen Sclerosus

- 1.

The pattern of distribution in males and females is strikingly different. While girls and women usually have a figure of eight pattern around the urethra and anus, peri-anal LS is virtually unheard of in males [ 15].

- 2.

In patients with a perineal urethrostomy, lichen sclerosus frequently develops at the site of the urethrostomy [25].

- 3.

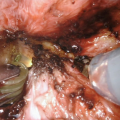

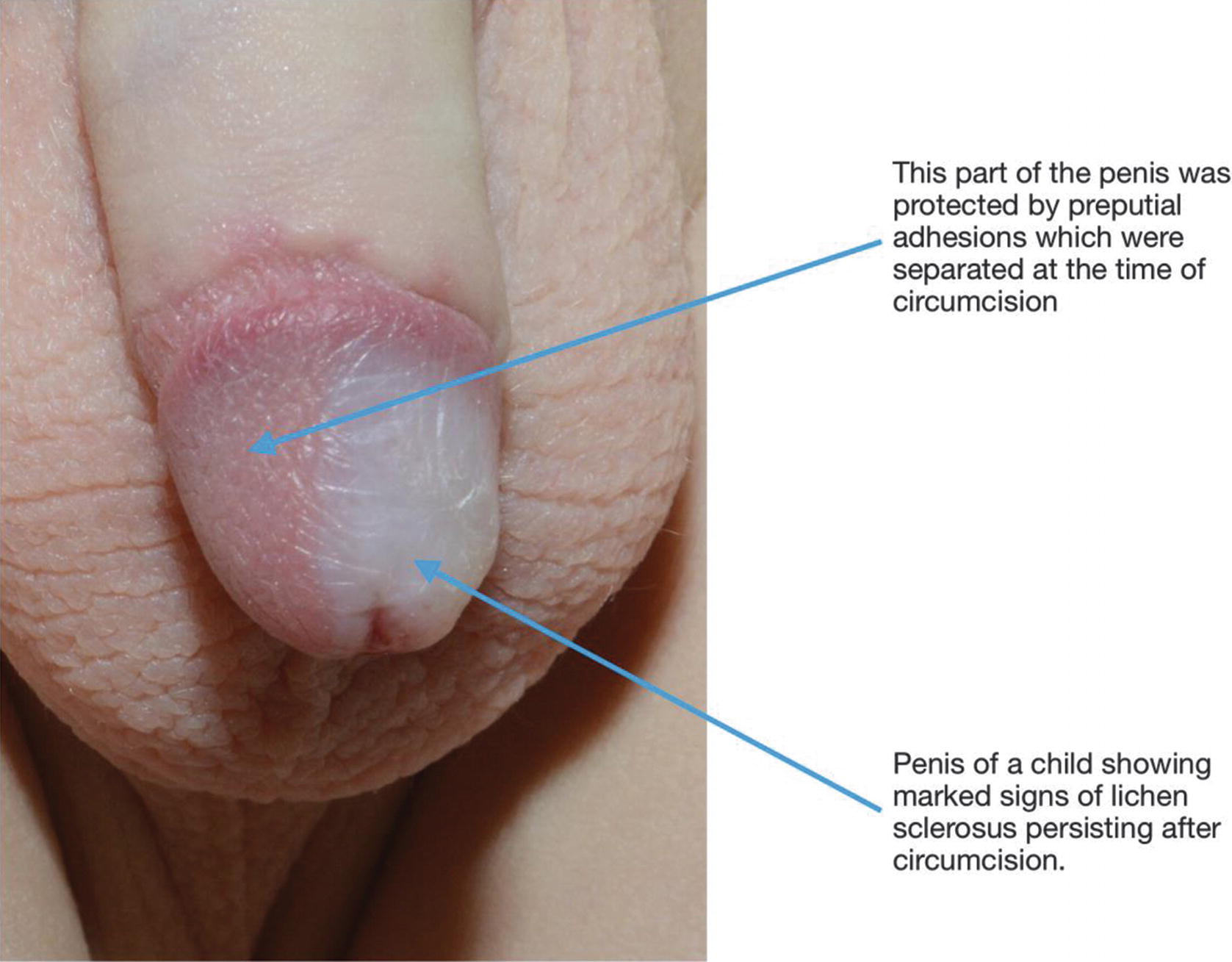

In children who have lichen sclerosus but still have congenital preputial adhesions, when the adhesions are separated, at the time of circumcision, the underlying skin is seen to have been protected by the adhesions (Fig. 51.3).

- 4.

Patients with LS have a much higher incidence of urinary dribbling than patients without LS [15].

- 5.

Patients with persistent skin folds over the penis after circumcision have a higher rate of recurrence [26].

The penis of a boy with lichen sclerosus to show that the glans skin, under the preputial adhesions separated at the time of circumcision, is not affected by the lichen sclerosus

51.6.1 The Difficult Circumcision

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree