Arthropod Bites and Stings: Introduction

|

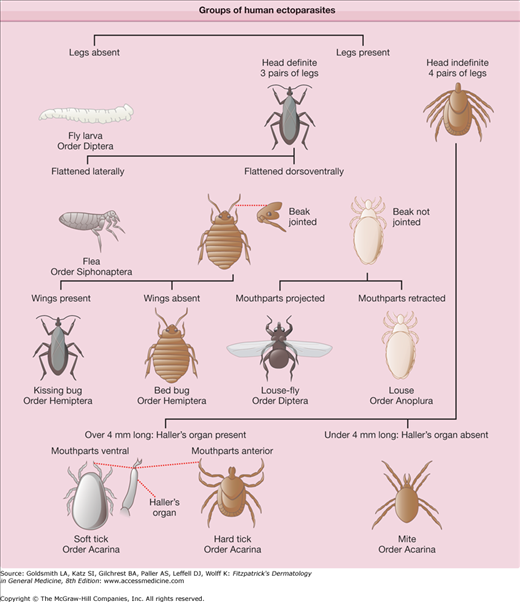

Arthropod bites and stings are a significant cause of morbidity worldwide. Although many arthropod attacks produce only mild, transient cutaneous changes, more severe local and systemic sequelae can occur, including potentially fatal toxic and anaphylactic reactions. Arthropods also serve as vectors for numerous systemic diseases. The medically significant classes of nonaquatic arthropods are Arachnida, Chilopoda, Diplopoda, and Insecta (Fig. 210-1).1

Histopathology

Many arthropod bites produce a similar histologic reaction pattern. In the acute phase, there is a superficial and deep, perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate, which is characteristically wedge shaped. The infiltrate is usually mixed in composition with an abundance of lymphocytes and eosinophils, although neutrophils and histiocytes can also be seen. Neutrophils may predominate in reactions to fleas, mosquitoes, fire ants, and brown recluse spiders. Over the most prominent superficial infiltrates, spongiosis can be seen, sometimes with progression to vesicle formation or epidermal necrosis. Older, excoriated areas are usually altered by the effects of scratching, with the development of parakeratosis, serum exudates, and a dermal infiltrate with neutrophils and more abundant lymphocytes. Although not commonly seen on histology, insects or insect parts, including burrowed scabies mites, eggs, feces, or the retained mouthparts of ticks, may be visible. Chronic lesions, which most often result when arthropod parts are retained in the skin, may have a pseudolymphomatous appearance (see Chapter 146).

Treatment Principles

The morbidity from arthropod bites and stings varies with the species inflicting the injury. Although species-specific clinical findings and treatment will be discussed in further detail, there are several applicable general treatment principles. Local wound care is essential following arthropod assault. Wounds should be cleansed; any remaining arthropod parts, including stingers, should be removed expeditiously. Patient discomfort should be addressed and can involve a variety of treatment modalities, including the use of ice packs, application of topical corticosteroids and antipruritics, injection of local anesthetics, and, less frequently, the use of systemic analgesics. Supportive measures for systemic toxic and allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, should be instituted when necessary. Secondary infection should be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Bites from several terrestrial arthropods species may require tetanus prophylaxis. Severe envenomation from particular species, such as the black widow spider, may require antivenom administration. Documented hypersensitivity to some species can be treated with desensitization immunotherapy. Awareness of the potential arthropod-borne illnesses spread by each species is also important.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Arachnida

The class Arachnida contains three orders of medical significance: (1) Araneae (spiders), (2) Acarina (ticks and mites), and (3) Scorpiones (scorpions). Arachnids are distinguished anatomically from other arthropods by a lack of wings or antennae and the presence of four pairs of legs and two body segments. Larval ticks, which only have three pairs of legs, are an exception to this rule (see Fig. 210-1).

Spiders are carnivorous members of the animal kingdom that use webs and venom to capture and kill prey. Within the United States, three genera contain species whose bites are toxic to man: (1) Latrodectus, (2) Loxosceles, and (3) Tegenaria. The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported over 15,000 spider bites in the United States in 2004.2 In the same year, only one death was attributed to spider envenomation in the United States.

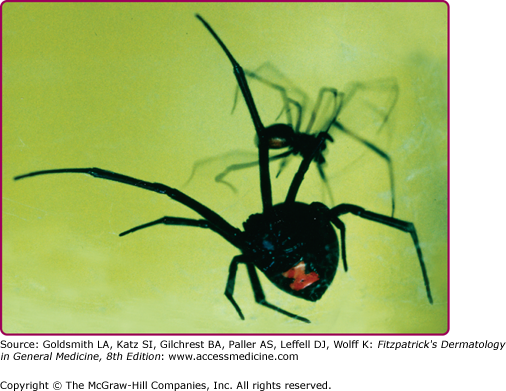

Members of the Latrodectus genus, or widow spiders, are often black in color and have a red, hourglass-shaped marking on their abdomens (Fig. 210-2). Although there are more than 20 species of widow spiders, Latrodectus mactans, the Southern black widow spider, is the most common and notorious in the United States and can be found in all but the most northern parts of the country. Other widow spiders encountered in the United States include Latrodectus various (Northern black widow), Latrodectus hesperus (Western black widow), Latrodectus bishopi (red-legged widow), and Latrodectus geometricus (brown widow). Members of the Latrodectus genus are nonaggressive, trapping spiders that spin webs in protected areas and await their prey. Human bites are often the result of accidental or deliberate provocation. Webs are typically found on the corners of doors and windows, underneath woodpiles, in garages and sheds, and on the undersides of eaves. Webs can also be found around outdoor toilet seats, a location that has led to bites on or near the genitalia.3

Bites of the black widow spider (L. mactans), which are often painful, usually only result in mild dermatologic manifestations. Within the first 30 minutes, localized erythema, piloerection, and sweating may appear at the wound site. A sensation of numbness or aching pain may develop shortly after the bite. Urticaria and cyanosis may occur at the bite site. Black widow venom contains the neurotoxin α-latrotoxin, which acts by opening ion channels at presynaptic nerve terminals, thereby causing an irreversible release of acetylcholine at motor nerve endings and catecholamines at adrenergic nerve endings.4 Consequently, black widow bites may produce agonizing crampy abdominal pain and muscle spasm that may mimic an acute abdomen.4 Other signs and symptoms include headache, paresthesias, nausea, vomiting, hypertension, lacrimation, salivation, seizures, tremors, acute renal failure, and sometimes, paralysis; fortunately, death is uncommon. Based on the spectrum of symptoms, black widow bite may be misdiagnosed as drug withdrawal, appendicitis, meningitis, or tetanus, to name a few.4

Although many widow spider bites require only local wound care, more serious reactions may necessitate hospitalization. Those patients at increased risk for serious complications include the very young, very old, and those with underlying cardiovascular disease. Current treatments for black widow envenomation include intravenous calcium gluconate (10%), narcotic analgesics, muscle relaxants, and benzodiazepines.5 L. mactans antivenom prepared from equine serum is also available. Additionally, there appears to be an effective cross-reactivity among antivenom for a number of other Latrodectus species.6–8 The benefits of the antivenom in treating complications of widow bites should be weighed against the potential for allergic reaction to the antivenom. Patients should also be up to date on tetanus immunization.

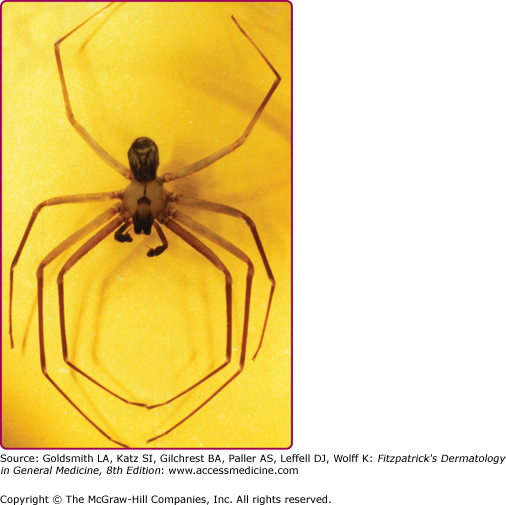

Members of the Loxosceles genus, also called recluse spiders or fiddle-back spiders, are nonaggressive spiders characterized by a dark brown marking on their cephalothorax in the shape of a fiddle or violin (Fig. 210-3). The brown recluse spider, Loxosceles reclusa, is the most well-known member of this genus and is most abundant in the American Midwest and Southeast. Other medically significant members of this genus include Loxosceles deserta (desert recluse), Loxosceles rufescens (Mediterranean recluse), Loxosceles kaiba (Grand Canyon recluse) and Loxosceles arizonica (Arizona recluse). Recluse spiders are so named because they will often seek out shelter in undisturbed places such as closets, attics, and storage areas for bedding and clothing. Bites usually occur when the spider feels threatened or provoked, such as when someone tries to put on clothing that contains the spider.1

Bites of the brown recluse spider (L. reclusa) vary from mild, local reactions to severe ulcerative necrosis, a reaction known as necrotic arachnidism. After a bite, transient erythema may develop with the formation of a central vesicle or papule. The hallmark “red, white, and blue” sign of a brown recluse bite is characterized by a central violaceous area surrounded by a rim of blanched skin that is further surrounded by a large asymmetric erythematous area (Fig. 210-4A). In a small percentage of cases, the initial wound may progress to necrosis (see Fig. 210-4B), which usually begins 2–3 days after the bite, with eschar formation occurring between the fifth and seventh days.9 Eventually deep ulcers develop. The bite reaction may mimic pyoderma gangrenosum or erythema migrans of Lyme disease.10 Cutaneous anthrax and chemical burns have been mistaken for a brown recluse spider bite.11,12 The potential for misdiagnosis has led to the development of a sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Loxosceles species venom that may eventually be available for clinical application.13

Brown recluse venom contains a number of proteins, including sphingomyelinase D, esterase, hyaluronidase, and alkaline phosphatase, which all contribute to tissue destruction. Sphingomyelinase D, the major component of the venom, cleaves sphingomyelin to form cermade-1-phosphate and choline and also hydrolyzes lysophosphatidylcholine to produce lysophosphatidic acid.14 Lysophosphatidic acid then triggers a proinflammatory response and causes platelet aggregation and increased vascular permeability.14 Sphingomyelinase D is also capable of inducing complement-mediated hemolysis.15 Systemic symptoms may develop within 1–2 days after envenomation and include nausea, vomiting, headache, fever, and chills. Rare but serious sequelae of brown recluse bites include renal failure, hemolytic anemia, hypotension, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.16,17

General treatment measures for recluse bites include cleansing the bite site and the application of cold compresses. Patients may also require analgesics to control pain. Antibiotics may be useful in reducing secondary bacterial infection of the wound site. Warm compresses and strenuous exercise should be avoided. Although Loxosceles antivenom have been developed and are frequently used in South America, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness, particularly against local cutaneous effects.8 A number of treatment modalities have been suggested, including hyperbaric oxygen, dapsone, intralesional and systemic corticosteroids, colchicine, and diphenhydramine.18,19 However, one study that used a rabbit model to compare dapsone, colchicine, intralesional triamcinolone, and diphenhydramine showed no effect on eschar size from any of these medications.18 Necrotic wounds heal slowly, sometimes over many months, and may require surgical excision and reconstruction to close the resulting defect. Surgical interventions should be delayed until the wound has stabilized.

Tegenaria agrestis, the hobo spider or “aggressive house spider,” is the predominant cause of necrotic arachnidism in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and can be found in an area ranging from Alaska to Utah.20 Although Loxosceles species are not typically found in the same geographic distribution, bites from hobo spiders are often mistaken for brown recluse bites. These spiders are brown in color with a gray herringbone pattern on the abdomen.21 The hobo spider typically builds funnel-shaped webs in crawl spaces, basements, wood piles, and bushes. Most hobo spider bites occur from July to September when the more venomous male spiders are seeking mates.

The local cutaneous effects after envenomation by the hobo spider, which can range from mild to serious, are similar to those caused by the brown recluse.22 The initial bite is often painless. Induration and paresthesia of the bite site may develop within 30 minutes. A large erythematous area may form around the site. Vesicle formation often occurs during the first 36 hours. Eschar formation may follow in severe cases, with necrosis and sloughing of the underlying tissue.

Wounds usually heal within several weeks. The most common systemic symptom after a hobo spider bite is a severe headache, which can persist for up to 1 week.23 Other symptoms may include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, paresthesias, and memory impairment. Although rare, death may ensue due to severe systemic effects, including aplastic anemia.23

Tarantulas are indigenous to certain regions of the United States and are also kept as exotic pets. Tarantulas are members of the family Theraphosidae and are hair covered and larger than many other types of spider, with leg spans of up to 12 inches reported in certain species. Unlike the other venomous spiders discussed, tarantula bites generally only produce mild local symptoms. However, more serious reactions can be caused by urticating hairs on the spider’s abdomen. When threatened, tarantulas may rub their back legs together in a motion that flicks these hairs off. These hairs may become embedded in the skin or eyes. Cutaneous responses to the hairs range from mild, local pruritus to granulomatous reactions. Ocular sequelae from hairs embedded in the cornea range from conjunctivitis and keratouveitis to corneal granulomas and chorioretinitis.24–27 Although cutaneous reactions can be treated with topical corticosteroids, ocular involvement requires ophthalmologic evaluation.

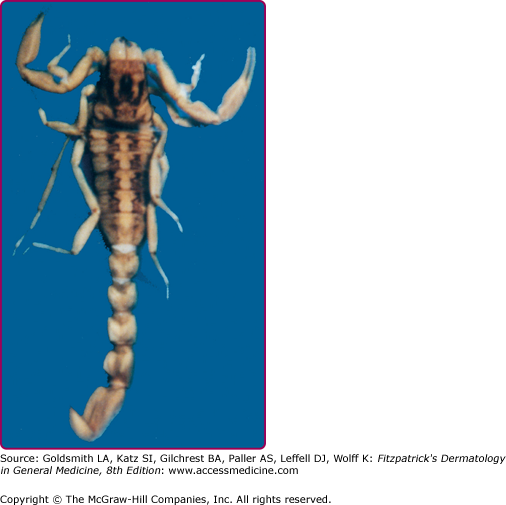

The order Scorpiones (scorpions) comprises terrestrial arachnids most commonly encountered in tropical or arid regions, including the southwestern United States, northern Africa, Mexico, and the Middle East. These nocturnal creatures seek shelter under stones and bark during the day. As with other arachnids, scorpions are generally shy and sting humans only when provoked. Although capable of producing significant local wounds, the potential for serious, even lethal, cardiovascular complications following a scorpion sting remains of primary concern.1 The scorpion of principal interest in the United States is Centruroides exilicauda (formerly Centruroides sculpturatus), whose sting is potentially fatal (Fig. 210-5). Centruroides species possess a small spine at the base of the stinger, a feature which may help distinguish them from other species of scorpion.28,29

Scorpion stings usually produce an immediate, sharp, burning pain. This may be followed by numbness extending beyond the sting site. Regional lymph node swelling, and, less commonly, ecchymosis and lymphangitis, may develop. C. exilicauda venom contains a powerful neurotoxin, capable of producing muscle spasticity, nystagmus, blurred vision, slurred speech, excessive salivation, respiratory distress, pulmonary edema, and myocarditis.30–35 Infants and young children are at the greatest risk for serious complications.29

Mild scorpion envenomations may only require symptomatic treatment, including analgesics and local ice compresses. Any child stung by a scorpion, especially if identified as C. exilicauda, should be hospitalized for close monitoring of respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic status.36 Specific antivenom is the treatment of choice for severe envenomation. Critically ill children with neurotoxic effects of scorpion envenomation can benefit greatly and promptly with intravenous administration of scorpion-specific F(ab′)(2) antivenom.29 Lack of it may have serious consequences. Studies indicate that C. exilicauda antivenom is safe, with a low incidence of anaphylactic reaction following infusion and a rapid onset of symptom relief.34,37 Although serum sickness is common after antivenom infusion, it is usually self-limited and can be managed with antihistamines and corticosteroids.34,37

The order Acarina contains ticks and mites (see Fig. 210-1). Ticks are the most numerous members of this order, with approximately 800 known species. They are important worldwide as vectors of systemic disease, capable of transmitting viruses, rickettsia, spirochetes, bacteria, and parasites to humans.

(See Chapter 208).

Ticks are divided into two families: (1) Ixodidae (hard ticks) and (2) Argasidae (soft ticks). Hard ticks are responsible for the majority of tick-related disease. Ticks pass through multiple stages during their life cycle, including egg, larva, nymph, and adult, and require blood meals for transition between the latter three stages. Ticks are distinguished from other mites by the presence of a barbed hypostome, which is inserted into the skin for feeding (Fig. 210-6). Ticks ingest blood from a diversity of vertebrate hosts including birds, reptiles, and mammals.38 Adult hard ticks are capable of ingesting several hundred times their unfed body weight when taking a blood meal and may survive for months without feeding. When searching for a suitable host, hard ticks exhibit a unique behavior called “questing” during which the tick crawls to the edge of a leaf or blade of grass and holds its front pair of legs stretched out in order to grab onto a passing host.39–41 Humans often become infested by contact with tall grass or brush that harbors the unfed ticks or by their association with domestic animals like cats or dogs. Ticks are attracted to the smell of sweat, the color white, and body heat. Once on a host, a tick may spend up to 24 hours in search of a protected site to feed, such as a skin fold or the hairline. Tick feeding time ranges from 2 hours to 7 days, with the tick dropping off of the host once fully engorged.

Many different tick species are responsible for local tick bite reactions and transmission of disease in human hosts. In the United States, Ixodes scapularis (deer tick or black-legged tick), Dermacentor andersoni (American wood tick), Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick), Ixodes pacificus (Western black-legged tick), and Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick) are among the most common. In the Eastern Hemisphere, important tick species include Ixodes ricinus (castor bean tick or sheep tick) and Ixodes persulcatus (Taiga tick). Among the diseases transmitted by ticks are Lyme disease (see Chapter 187), ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (see Chapter 199), Colorado tick fever, Q fever, and tularemia (see Chapter 180).

The majority of tick bites occur in the spring and summer, coinciding with the life cycle of the tick. Tick bites are usually painless, as the tick introduces an anesthetic and anticoagulant substance when biting. Often, a person will not even know he or she has been bitten, but will see or feel an attached tick while scratching or bathing. Tick bites may incite foreign body granuloma formation, reactions to injected toxins and salivary secretions, and other hypersensitivity responses. Rarely, delayed hypersensitivity reactions occur with fever, pruritus, and urticaria.42 A red papule is usually seen at the bite site, and may progress to localized swelling and erythema.42,43 A cellular response to the bite can lead to induration and nodularity after a few days. Foreign-body reactions may occur when mouthparts are retained in skin after incomplete removal of the tick. Chronic tick bite granulomas may present diagnostic problems and persist for months to years.

Tick paralysis is a potentially lethal complication of tick infestation and is thought to be caused by a neurotoxin contained within tick salivary secretions. The illness may start with headache and malaise and rapidly progress to an acute ascending lower motor neuron paralysis, similar to that of Guillain–Barré syndrome, which may result in respiratory failure and death.44,45 Several species of tick are capable of causing tick paralysis, including D. andersoni, D. variabilis, and A. americanum. Typically, the onset of symptoms occurs 4–6 days after attachment of the tick. Symptoms resolve once the tick is removed from the patient. Supportive measures, including mechanical ventilation, may be required until symptoms resolve.

After potential exposure, the skin should be inspected for ticks to remove them before they begin feeding and risk transmitting disease. Once a tick has inserted its hypostome into the skin, it must be forcibly removed. Although many methods have been suggested for removing ticks, physical methods, such as slow, steady pulling on the tick, are probably the safest and most useful. Retained tick parts should be removed surgically if necessary to prevent development of foreign body granulomas. Antibiotic prophylaxis after tick bites is controversial. Although there is some evidence that prophylaxis may help prevent acquisition of Lyme disease and other vector-borne illnesses, the risks of antibiotic therapy must be weighed against the risks and prevalence of vector-borne illnesses in a particular region. In areas highly endemic for Lyme disease, the benefits of prophylactic treatment may outweigh the risks, especially in cases in which the tick has been attached to the host for an extended period of time and can accurately be identified as a vector for Lyme borreliosis. In these cases, the authors suggest a course of oral doxycycline (see Chapter 187).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree